Chapter 9: Gases

9.6 Effusion and Diffusion of Gases

Learning Outcomes

- Use Graham's Law to calculate the relative rates of effusion of gases

If you have ever been in a room when a piping hot pizza was delivered, you have been made aware of the fact that gaseous molecules can quickly spread throughout a room, as evidenced by the pleasant aroma that soon reaches your nose. Although gaseous molecules travel at tremendous speeds (hundreds of meters per second), they collide with other gaseous molecules and travel in many different directions before reaching the desired target. At room temperature, a gaseous molecule will experience billions of collisions per second. The mean free path is the average distance a molecule travels between collisions. The mean free path increases with decreasing pressure; in general, the mean free path for a gaseous molecule will be hundreds of times the diameter of the molecule.

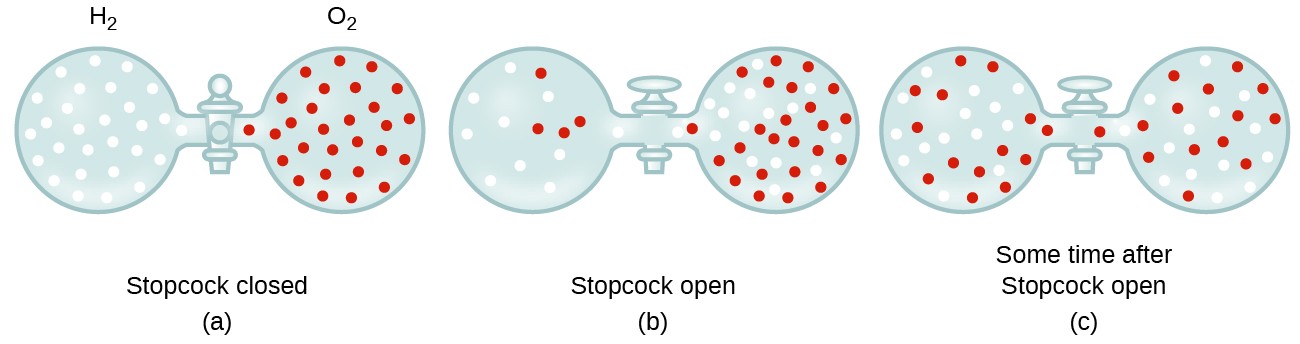

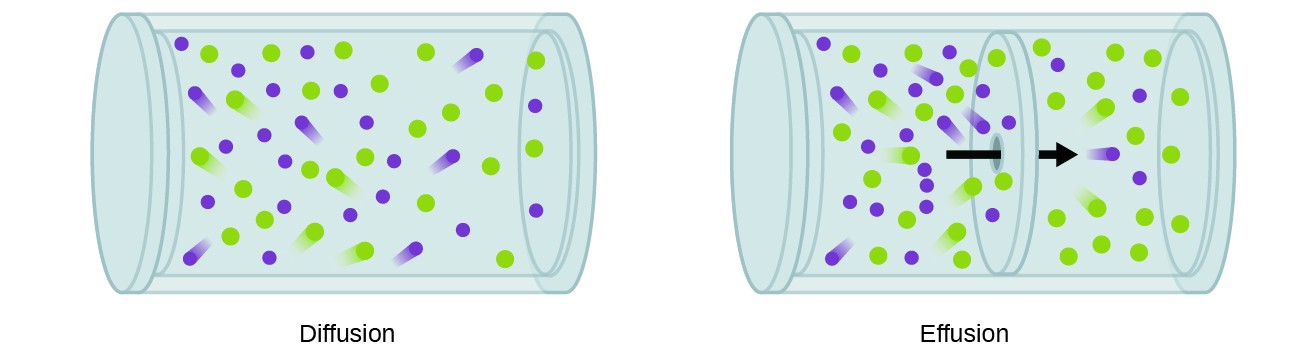

In general, we know that when a sample of gas is introduced to one part of a closed container, its molecules very quickly disperse throughout the container; this process by which molecules disperse in space in response to differences in concentration is called diffusion (shown in Figure 9.6.1). The gaseous atoms or molecules are, of course, unaware of any concentration gradient, they simply move randomly—regions of higher concentration have more particles than regions of lower concentrations, and so a net movement of species from high to low concentration areas takes place. In a closed environment, diffusion will ultimately result in equal concentrations of gas throughout, as depicted in Figure 9.6.1. The gaseous atoms and molecules continue to move, but since their concentrations are the same in both bulbs, the rates of transfer between the bulbs are equal (no net transfer of molecules occurs).

We are often interested in the rate of diffusion, the amount of gas passing through some area per unit time:

[latex]\text{rate of diffusion}=\dfrac{\text{amount of gas passing through an area}}{\text{unit of time}}[/latex]

The diffusion rate depends on several factors: the concentration gradient (the increase or decrease in concentration from one point to another); the amount of surface area available for diffusion; and the distance the gas particles must travel. Note also that the time required for diffusion to occur is inversely proportional to the rate of diffusion, as shown in the rate of diffusion equation.

A process involving movement of gaseous species similar to diffusion is effusion, the escape of gas molecules through a tiny hole such as a pinhole in a balloon into a vacuum (Figure 9.6.2). Although diffusion and effusion rates both depend on the molar mass of the gas involved, their rates are not equal; however, the ratios of their rates are the same.

If a mixture of gases is placed in a container with porous walls, the gases effuse through the small openings in the walls. The lighter gases pass through the small openings more rapidly (at a higher rate) than the heavier ones (Figure 9.6.3). In 1832, Thomas Graham studied the rates of effusion of different gases and formulated Graham’s law of effusion: The rate of effusion of a gas is inversely proportional to the square root of the mass of its particles:

[latex]\text{rate of effusion}\propto \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{\mathscr{M}}}[/latex]

This means that if two gases A and B are at the same temperature and pressure, the ratio of their effusion rates is inversely proportional to the ratio of the square roots of the masses of their particles:

[latex]\dfrac{\text{rate of effusion of A}}{\text{rate of effusion of B}}=\dfrac{\sqrt{\mathscr{M}_{\text{B}}}}{\sqrt{\mathscr{M}_{\text{A}}}}[/latex]

Example 9.6.1: Applying Graham’s Law to Rates of Effusion

Calculate the ratio of the rate of effusion of hydrogen to the rate of effusion of oxygen.

Show Solution

From Graham’s law, we have:

[latex]\dfrac{\text{rate of effusion of hydrogen}}{\text{rate of effusion of oxygen}}=\dfrac{\sqrt{1.43\cancel{{\text{g L}}^{-\text{1}}}}}{\sqrt{0.0899\cancel{{\text{g L}}^{-\text{1}}}}}=\dfrac{1.20}{0.300}=\dfrac{4}{1}[/latex]

Using molar masses:

[latex]\dfrac{\text{rate of effusion of hydrogen}}{\text{rate of effusion of oxygen}}=\dfrac{\sqrt{32\cancel{{\text{g mol}}^{-\text{1}}}}}{\sqrt{2\cancel{{\text{g mol}}^{-\text{1}}}}}=\dfrac{\sqrt{16}}{\sqrt{1}}=\dfrac{4}{1}[/latex] Hydrogen effuses four times as rapidly as oxygen.

Check Your Learning

Here’s another example, making the point about how determining times differs from determining rates.

Example 9.6.2: Effusion Time Calculations

It takes 243 s for 4.46 × 10-5 mol Xe to effuse through a tiny hole. Under the same conditions, how long will it take 4.46 × 10–5 mol Ne to effuse?

Show Solution

It is important to resist the temptation to use the times directly, and to remember how rate relates to time as well as how it relates to mass. Recall the definition of rate of effusion: [latex]\text{rate of effusion}=\dfrac{\text{amount of gas transferred}}{\text{time}}[/latex] and combine it with Graham’s law:

[latex]\displaystyle\dfrac{\text{rate of effusion of gas } \ce{Xe}}{\text{rate of effusion of gas Ne}}=\dfrac{\sqrt{{\mathscr{M}}_{\ce{Ne}}}}{\sqrt{{\mathscr{M}}_{\ce{Xe}}}}[/latex]

To get:

[latex]\displaystyle\dfrac{\dfrac{\text{amount of } \ce{Xe} \text{ transferred}}{\text{time for} \ce{Xe}}}{\dfrac{\text{amount of } \ce{Ne} \text{ transferred}}{\text{time for } \ce{Ne}}}=\dfrac{\sqrt{{\mathscr{M}}_{\text{Ne}}}}{\sqrt{{\mathscr{M}}_{\text{Xe}}}}[/latex]

Noting that amount of A = amount of B, and solving for time for [latex]\ce{Ne}[/latex]:

[latex]\displaystyle\dfrac{\dfrac{\cancel{\text{amount of } \ce{Xe}}}{\text{time for } \ce{Xe}}}{\dfrac{\cancel{\text{amount of } \ce{Ne}}}{\text{time for Ne}}}=\dfrac{\text{time for } \ce{Ne}}{\text{time for } \ce{Xe}}=\dfrac{\sqrt{{\mathscr{M}}_{\ce{Ne}}}}{\sqrt{{\mathscr{M}}_{\ce{Xe}}}}=\dfrac{\sqrt{{\mathscr{M}}_{\ce{Ne}}}}{\sqrt{{\mathscr{M}}_{\ce{Xe}}}}[/latex]

and substitute values:

[latex]\dfrac{\text{time for } \ce{Ne}}{243\text{s}}=\sqrt{\dfrac{20.2\cancel{\text{g mol}}}{131.3\cancel{\text{g mol}}}}=0.392[/latex]

Finally, solve for the desired quantity:

[latex]\text{time for Ne}=0.392\times 243\text{s}=95.3\text{s}[/latex]

Note that this answer is reasonable: Since [latex]\ce{Ne}[/latex] is lighter than [latex]\ce{Xe}[/latex], the effusion rate for [latex]\ce{Ne}[/latex] will be larger than that for [latex]\ce{Xe}[/latex], which means the time of effusion for Ne will be smaller than that for [latex]\ce{Xe}[/latex].

Check Your Learning

Finally, here is one more example showing how to calculate molar mass from effusion rate data.

Example 9.6.3: Determining Molar Mass Using Graham’s Law

An unknown gas effuses 1.66 times more rapidly than [latex]\ce{CO2}[/latex]. What is the molar mass of the unknown gas? Can you make a reasonable guess as to its identity?

Show Solution

From Graham’s law, we have:

[latex]\dfrac{\text{rate of effusion of Unknown}}{{\text{rate of effusion of } \ce{CO}}_{2}}=\dfrac{\sqrt{{\mathscr{M}}_{{\ce{CO}}_{2}}}}{\sqrt{{\mathscr{M}}_{Unknown}}}[/latex]

Plug in known data:

[latex]\dfrac{1.66}{1}=\dfrac{\sqrt{44.0\text{g/mol}}}{\sqrt{{\mathscr{M}}_{Unknown}}}[/latex]

Solve:

[latex]{\mathscr{M}}_{Unknown}=\dfrac{44.0\text{g/mol}}{{\left(1.66\right)}^{2}}=16.0\text{g/mol}[/latex]

The gas could well be [latex]\ce{CH4}[/latex], the only gas with this molar mass.

Check Your Learning

Key Concepts and Summary

Gaseous atoms and molecules move freely and randomly through space. Diffusion is the process whereby gaseous atoms and molecules are transferred from regions of relatively high concentration to regions of relatively low concentration. Effusion is a similar process in which gaseous species pass from a container to a vacuum through very small orifices. The rates of effusion of gases are inversely proportional to the square roots of their densities or to the square roots of their atoms/molecules’ masses (Graham’s law).

Key Equations

- [latex]\text{rate of diffusion}=\dfrac{\text{amount of gas passing through an area}}{\text{unit of time}}[/latex]

- [latex]\dfrac{\text{rate of effusion of gas A}}{\text{rate of effusion of gas B}}=\dfrac{\sqrt{{m}_{B}}}{\sqrt{{m}_{A}}}=\dfrac{\sqrt{{\mathscr{M}}_{B}}}{\sqrt{{\mathscr{M}}_{A}}}[/latex]

Try It

- Heavy water, [latex]\ce{D2O}[/latex] (molar mass = 20.03 g mol–1), can be separated from ordinary water, [latex]\ce{H2O}[/latex] (molar mass = 18.01), as a result of the difference in the relative rates of diffusion of the molecules in the gas phase. Calculate the relative rates of diffusion of [latex]\ce{H2O}[/latex] and [latex]\ce{D2O}[/latex].

- Which of the following gases diffuse more slowly than oxygen? [latex]\ce{F2}[/latex], [latex]\ce{Ne}[/latex], [latex]\ce{N2O}[/latex], [latex]\ce{C2H2}[/latex], [latex]\ce{NO}[/latex], [latex]\ce{Cl2}[/latex], [latex]\ce{H2S}[/latex]

- A gas of unknown identity diffuses at a rate of 83.3 mL/s in a diffusion apparatus in which carbon dioxide diffuses at the rate of 102 mL/s. Calculate the molecular mass of the unknown gas.

Selected Answers

- Gases with molecular masses greater than that of oxygen (31.9988 g/mol) will diffuse more slowly than [latex]\ce{O2}[/latex]. These gases are [latex]\ce{F2}[/latex] (37.9968 g/mol), [latex]\ce{N2O}[/latex] (44.0128 g/mol ), [latex]\ce{Cl2}[/latex] (70.906 g/mol), and [latex]\ce{H2S}[/latex] (34.082 g/mol).

Glossary

diffusion: movement of an atom or molecule from a region of relatively high concentration to one of relatively low concentration (discussed in this chapter with regard to gaseous species, but applicable to species in any phase)

effusion: transfer of gaseous atoms or molecules from a container to a vacuum through very small openings

Graham’s law of effusion: rates of diffusion and effusion of gases are inversely proportional to the square roots of their molecular masses

mean free path: average distance a molecule travels between collisions

rate of diffusion: amount of gas diffusing through a given area over a given time

Licenses and Attributions (Click to expand)

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- Chemistry 2e. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: https://openstax.org/. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Access for free at

https://openstax.org/books/chemistry-2e/pages/1-introduction

average distance a molecule travels between collisions

movement of an atom or molecule from a region of relatively high concentration to one of relatively low concentration (discussed in this chapter with regard to gaseous species, but applicable to species in any phase)

amount of gas diffusing through a given area over a given time

transfer of gaseous atoms or molecules from a container to a vacuum through very small openings

rates of diffusion and effusion of gases are inversely proportional to the square roots of their molecular masses