Chapter 17: Electrochemistry

17.7 Corrosion

Learning Outcomes

- Define corrosion

- List some of the methods used to prevent or slow corrosion

Corrosion is usually defined as the degradation of metals due to an electrochemical process. The formation of rust on iron, tarnish on silver, and the blue-green patina that develops on copper are all examples of corrosion. The total cost of corrosion in the United States is significant, with estimates in excess of half a trillion dollars a year.

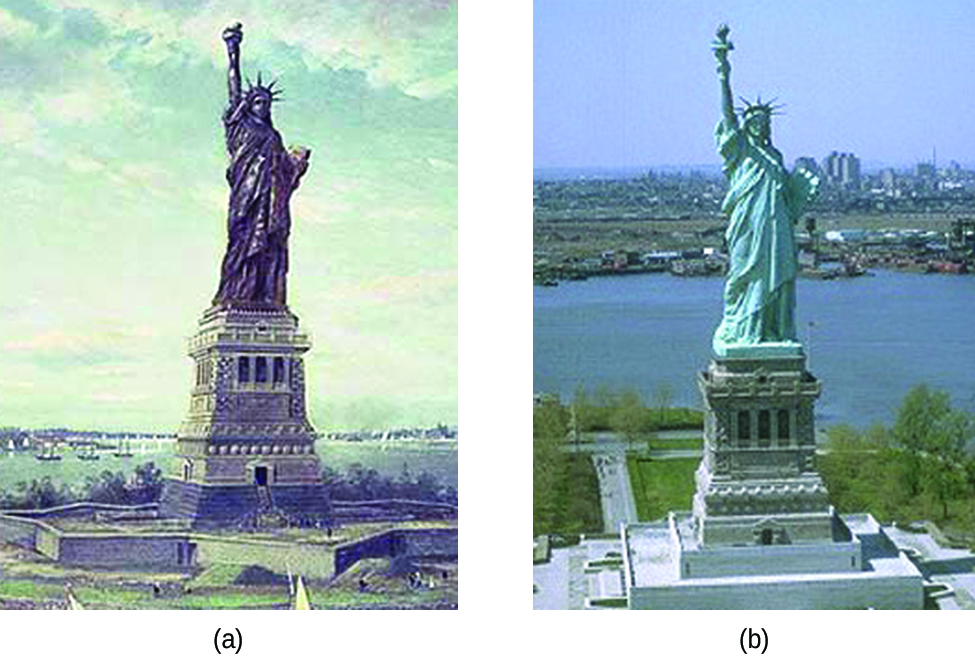

Statue of Liberty: Changing Colors

The Statue of Liberty is a landmark every American recognizes. The Statue of Liberty is easily identified by its height, stance, and unique blue-green color (Figure 17.7.1). When this statue was first delivered from France, its appearance was not green. It was brown, the color of its copper “skin.” So how did the Statue of Liberty change colors? The change in appearance was a direct result of corrosion. The copper that is the primary component of the statue slowly underwent oxidation from the air. The oxidation-reduction reactions of copper metal in the environment occur in several steps. Copper metal is oxidized to copper(I) oxide ([latex]\ce{Cu2O}[/latex]), which is red, and then to copper(II) oxide, which is black.

[latex]\ce{2Cu}(s) + \frac{1}{2}\ce{O2}(g) \longrightarrow \ce{Cu2O}(s) \,\,\,\,\,\text{(red)}[/latex]

[latex]\ce{Cu2O}(s) + \frac{1}{2}\ce{O2}(g) \longrightarrow \ce{2CuO}(s) \,\,\,\,\,\text{(black)}[/latex]

Coal, which was often high in sulfur, was burned extensively in the early part of the last century. As a result, sulfur trioxide, carbon dioxide, and water all reacted with the [latex]\ce{CuO}[/latex]

[latex]\ce{2CuO}(s) + \ce{CO2}(g) + \ce{H2O}(l) \longrightarrow \ce{Cu2CO3(OH)2}(s) \,\,\,\,\,\text{(green)}[/latex]

[latex]\ce{3CuO}(s) + \ce{2CO2}(g) + \ce{H2O}(l) \longrightarrow \ce{Cu2(CO3)2(OH)2}(s) \,\,\,\,\,\text{(blue)}[/latex]

[latex]\ce{4CuO}(s) + \ce{SO3}(g) + \ce{3H2O}(l) \longrightarrow \ce{Cu4SO4(OH)6}(s) \,\,\,\,\,\text{(green)}[/latex]

These three compounds are responsible for the characteristic blue-green patina seen today. Fortunately, formation of the patina created a protective layer on the surface, preventing further corrosion of the copper skin. The formation of the protective layer is a form of passivation, which is discussed further in a later chapter.

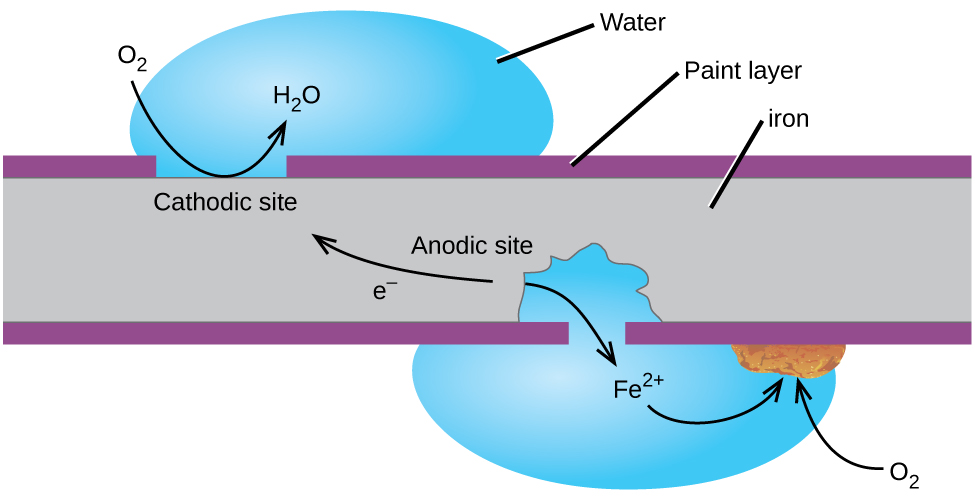

Perhaps the most familiar example of corrosion is the formation of rust on iron. Iron will rust when it is exposed to oxygen and water. Rust formation involves the creation of a galvanic cell at an iron surface, as illustrated in Figure 17.7.2. The relevant redox reactions are described by the following equations:

[latex]\text{anode:} \,\,\,\, \ce{Fe}(s) \longrightarrow \ce{Fe^2+}(aq) + \ce{2e-} \,\,\,\,\,\, E^\circ_{\ce{Fe^2+}/\ce{Fe}} = −0.44 \text{V}[/latex]

[latex]\text{cathode:} \,\,\,\,\ce{O2}(g) + \ce{4H+}(aq) + \ce{4e-} \longrightarrow \ce{2H2O}(l) \,\,\,\,\,\, E^\circ_{\ce{O2}/\ce{O^2}} = +1.23 \text{V}[/latex]

[latex]\text{overall:} \,\,\,\, \ce{2Fe}(s) + \ce{O2}(g) + \ce{4H+}(aq) \longrightarrow \ce{2Fe^2+}(aq) + \ce{2H2O}(l) \,\,\,\,\,\, E^\circ_{cell} = +1.67 \text{V}[/latex]

Further reaction of the iron(II) product in humid air results in the production of an iron(III) oxide hydrate known as rust:

[latex]\ce{4Fe^2+}(aq) + \ce{O2}(g) + (4 + 2x)\ce{H2O}(l) \longrightarrow \ce{2Fe2O3}\cdot x\ce{H2O}(s) + \ce{8H+}(aq)[/latex]

The stoichiometry of the hydrate varies, as indicated by the use of x in the compound formula. Unlike the patina on copper, the formation of rust does not create a protective layer and so corrosion of the iron continues as the rust flakes off and exposes fresh iron to the atmosphere.

One way to keep iron from corroding is to keep it painted. The layer of paint prevents the water and oxygen necessary for rust formation from coming into contact with the iron. As long as the paint remains intact, the iron is protected from corrosion.

Other strategies include alloying the iron with other metals. For example, stainless steel is mostly iron with a bit of chromium. The chromium tends to collect near the surface, where it forms an oxide layer that protects the iron.

Iron and other metals may also be protected from corrosion by galvanization, a process in which the metal to be protected is coated with a layer of a more readily oxidized metal, usually zinc. When the zinc layer is intact, it prevents air from contacting the underlying iron and thus prevents corrosion. If the zinc layer is breached by either corrosion or mechanical abrasion, the iron may still be protected from corrosion by a cathodic protection process, which is described in the next paragraph.

Another important way to protect metal is to make it the cathode in a galvanic cell. This is cathodic protection and can be used for metals other than just iron. For example, the rusting of underground iron storage tanks and pipes can be prevented or greatly reduced by connecting them to a more active metal such as zinc or magnesium (Figure 17.7.3). This is also used to protect the metal parts in water heaters. The more active metals (lower reduction potential) are called sacrificial anodes because as they get used up as they corrode (oxidize) at the anode. The metal being protected serves as the cathode, and so does not oxidize (corrode). When the anodes are properly monitored and periodically replaced, the useful lifetime of the iron storage tank can be greatly extended.

Key Concepts and Summary

Spontaneous oxidation of metals by natural electrochemical processes is called corrosion, familiar examples including the rusting of iron and the tarnishing of silver. Corrosion process involve the creation of a galvanic cell in which different sites on the metal object function as anode and cathode, with the corrosion taking place at the anodic site. Approaches to preventing corrosion of metals include use of a protective coating of zinc (galvanization) and the use of sacrificial anodes connected to the metal object (cathodic protection).

Try It

- Which member of each pair of metals is more likely to corrode (oxidize)?

- [latex]\ce{Mg}[/latex] or [latex]\ce{Ca}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Au}[/latex] or [latex]\ce{Hg}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Fe}[/latex] or [latex]\ce{Zn}[/latex]

- [latex]\ce{Ag}[/latex] or [latex]\ce{Pt}[/latex]

- Consider the following metals: [latex]\ce{Ag}[/latex], [latex]\ce{Au}[/latex], [latex]\ce{Mg}[/latex], [latex]\ce{Ni}[/latex], and [latex]\ce{Zn}[/latex]. Which of these metals could be used as a sacrificial anode in the cathodic protection of an underground steel storage tank? Steel is mostly iron, so use −0.447 V as the standard reduction potential for steel.

- Aluminum (E∘Al3+/Al=−2.07 V) is more easily oxidized than iron (E∘Fe3+/Fe=−0.477 V), and yet when both are exposed to the environment, untreated aluminum has very good corrosion resistance while the corrosion resistance of untreated iron is poor. Explain this observation.

- If a sample of iron and a sample of zinc come into contact, the zinc corrodes but the iron does not. If a sample of iron comes into contact with a sample of copper, the iron corrodes but the copper does not. Explain this phenomenon.

- Suppose you have three different metals, A, B, and C. When metals A and B come into contact, B corrodes and A does not corrode. When metals A and C come into contact, A corrodes and C does not corrode. Based on this information, which metal corrodes and which metal does not corrode when B and C come into contact?

- Why would a sacrificial anode made of lithium metal be a bad choice despite its E∘Li+/Li=−3.04 V, which appears to be able to protect all the other metals listed in the standard reduction potential table?

Show Selected Solutions

- Mg and Zn

- Both examples involve cathodic protection. The (sacrificial) anode is the metal that corrodes (oxidizes or reacts). In the case of iron (−0.447 V) and zinc (−0.7618 V), zinc has a more negative standard reduction potential and so serves as the anode. In the case of iron and copper (0.34 V), iron has the smaller standard reduction potential and so corrodes (serves as the anode).

- While the reduction potential of lithium would make it capable of protecting the other metals, this high potential is also indicative of how reactive lithium is; it would have a spontaneous reaction with most substances. This means that the lithium would react quickly with other substances, even those that would not oxidize the metal it is attempting to protect. Reactivity like this means the sacrificial anode would be depleted rapidly and need to be replaced frequently. (Optional additional reason: fire hazard in the presence of water.)

Glossary

cathodic protection: method of protecting metal by using a sacrificial anode and effectively making the metal that needs protecting the cathode, thus preventing its oxidation

corrosion: degradation of metal through an electrochemical process

galvanized iron: method for protecting iron by covering it with zinc, which will oxidize before the iron; zinc-plated iron

sacrificial anode: more active, inexpensive metal used as the anode in cathodic protection; frequently made from magnesium or zinc

Licenses and Attributions (Click to expand)

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- Chemistry 2e. Provided by: OpenStax. Located at: https://openstax.org/. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Access for free at

https://openstax.org/books/chemistry-2e/pages/1-introduction

degradation of metal through an electrochemical process

method for protecting iron by covering it with zinc, which will oxidize before the iron; zinc-plated iron

method of protecting metal by using a sacrificial anode and effectively making the metal that needs protecting the cathode, thus preventing its oxidation

more active, inexpensive metal used as the anode in cathodic protection; frequently made from magnesium or zinc