Chapter 3. The First Law of Thermodynamics

3.3 First Law of Thermodynamics

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- State the first law of thermodynamics and explain how it is applied

- Explain how heat transfer, work done, and internal energy change are related in any thermodynamic process

Now that we have seen how to calculate internal energy, heat, and work done for a thermodynamic system undergoing change during some process, we can see how these quantities interact to affect the amount of change that can occur. This interaction is given by the first law of thermodynamics. British scientist and novelist C. P. Snow (1905–1980) is credited with a joke about the four laws of thermodynamics. His humorous statement of the first law of thermodynamics is stated “you can’t win,” or in other words, you cannot get more energy out of a system than you put into it. We will see in this chapter how internal energy, heat, and work all play a role in the first law of thermodynamics.

Suppose Q represents the heat exchanged between a system and the environment, and W is the work done by or on the system. The first law states that the change in internal energy of that system is given by [latex]Q-W[/latex]. Since added heat increases the internal energy of a system, Q is positive when it is added to the system and negative when it is removed from the system.

When a gas expands, it does work and its internal energy decreases. Thus, W is positive when work is done by the system and negative when work is done on the system. This sign convention is summarized in Table 3.1. The first law of thermodynamics is stated as follows:

First Law of Thermodynamics

Associated with every equilibrium state of a system is its internal energy [latex]{E}_{\text{int}}.[/latex] The change in [latex]{E}_{\text{int}}[/latex] for any transition between two equilibrium states is

where Q and W represent, respectively, the heat exchanged by the system and the work done by or on the system.

| Thermodynamic Sign Conventions for Heat and Work | |

|---|---|

| Process | Convention |

| Heat added to system | [latex]Q>0[/latex] |

| Heat removed from system | [latex]Q < 0[/latex] |

| Work done by system | [latex]W>0[/latex] |

| Work done on system | [latex]W < 0[/latex] |

The first law is a statement of energy conservation. It tells us that a system can exchange energy with its surroundings by the transmission of heat and by the performance of work. The net energy exchanged is then equal to the change in the total mechanical energy of the molecules of the system (i.e., the system’s internal energy). Thus, if a system is isolated, its internal energy must remain constant.

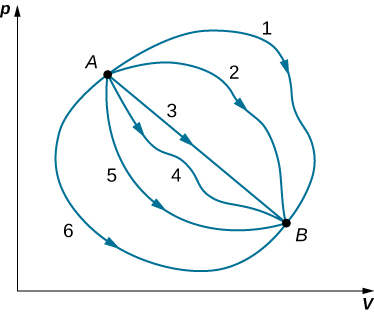

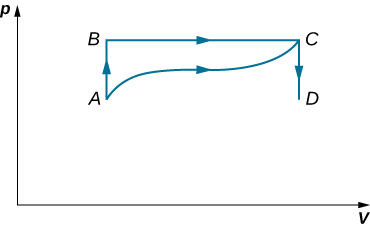

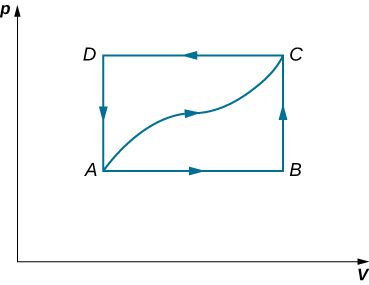

Although Q and W both depend on the thermodynamic path taken between two equilibrium states, their difference [latex]Q-W[/latex] does not. Figure 3.7 shows the pV diagram of a system that is making the transition from A to B repeatedly along different thermodynamic paths. Along path 1, the system absorbs heat [latex]{Q}_{1}[/latex] and does work [latex]{W}_{1};[/latex] along path 2, it absorbs heat [latex]{Q}_{2}[/latex] and does work [latex]{W}_{2},[/latex] and so on. The values of [latex]{Q}_{i}[/latex] and [latex]{W}_{i}[/latex] may vary from path to path, but we have

or

That is, the change in the internal energy of the system between A and B is path independent. In the chapter on potential energy and the conservation of energy, we encountered another path-independent quantity: the change in potential energy between two arbitrary points in space. This change represents the negative of the work done by a conservative force between the two points. The potential energy is a function of spatial coordinates, whereas the internal energy is a function of thermodynamic variables. For example, we might write [latex]{E}_{\text{int}}\left(T,p\right)[/latex] for the internal energy. Functions such as internal energy and potential energy are known as state functions because their values depend solely on the state of the system.

Often the first law is used in its differential form, which is

Here [latex]d{E}_{\text{int}}[/latex] is an infinitesimal change in internal energy when an infinitesimal amount of heat dQ is exchanged with the system and an infinitesimal amount of work dW is done by (positive in sign) or on (negative in sign) the system.

Example

Changes of State and the First Law

During a thermodynamic process, a system moves from state A to state B, it is supplied with 400 J of heat and does 100 J of work. (a) For this transition, what is the system’s change in internal energy? (b) If the system then moves from state B back to state A, what is its change in internal energy? (c) If in moving from A to B along a different path, [latex]{{W}^{\prime }}_{AB}=400\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J}[/latex] of work is done on the system, how much heat does it absorb?

Strategy

The first law of thermodynamics relates the internal energy change, work done by the system, and the heat transferred to the system in a simple equation. The internal energy is a function of state and is therefore fixed at any given point regardless of how the system reaches the state.

Solution

Show Answer

- From the first law, the change in the system’s internal energy is

- Consider a closed path that passes through the states A and B. Internal energy is a state function, so [latex]\text{Δ}{E}_{\text{int}}[/latex] is zero for a closed path. Thus

and

This yields

- The change in internal energy is the same for any path, so

and the heat exchanged is

The negative sign indicates that the system loses heat in this transition.

Significance

When a closed cycle is considered for the first law of thermodynamics, the change in internal energy around the whole path is equal to zero. If friction were to play a role in this example, less work would result from this heat added. Example 3.3 takes into consideration what happens if friction plays a role.

Notice that in Example 3.2, we did not assume that the transitions were quasi-static. This is because the first law is not subject to such a restriction. It describes transitions between equilibrium states but is not concerned with the intermediate states. The system does not have to pass through only equilibrium states. For example, if a gas in a steel container at a well-defined temperature and pressure is made to explode by means of a spark, some of the gas may condense, different gas molecules may combine to form new compounds, and there may be all sorts of turbulence in the container—but eventually, the system will settle down to a new equilibrium state. This system is clearly not in equilibrium during its transition; however, its behavior is still governed by the first law because the process starts and ends with the system in equilibrium states.

Example

Polishing a Fitting

A machinist polishes a 0.50-kg copper fitting with a piece of emery cloth for 2.0 min. He moves the cloth across the fitting at a constant speed of 1.0 m/s by applying a force of 20 N, tangent to the surface of the fitting. (a) What is the total work done on the fitting by the machinist? (b) What is the increase in the internal energy of the fitting? Assume that the change in the internal energy of the cloth is negligible and that no heat is exchanged between the fitting and its environment. (c) What is the increase in the temperature of the fitting?

Strategy

The machinist’s force over a distance that can be calculated from the speed and time given is the work done on the system. The work, in turn, increases the internal energy of the system. This energy can be interpreted as the heat that raises the temperature of the system via its heat capacity. Be careful with the sign of each quantity.

Solution

Show Answer

- The power created by a force on an object or the rate at which the machinist does frictional work on the fitting is [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{F}}·\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{v}}=\text{−}Fv[/latex]. Thus, in an elapsed time [latex]\text{Δ}t[/latex] (2.0 min), the work done on the fitting is

- By assumption, no heat is exchanged between the fitting and its environment, so the first law gives for the change in the internal energy of the fitting:

- Since [latex]\text{Δ}{E}_{\text{int}}[/latex] is path independent, the effect of the [latex]2.4\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{3}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J}[/latex] of work is the same as if it were supplied at atmospheric pressure by a transfer of heat. Thus,

and the increase in the temperature of the fitting is

where we have used the value for the specific heat of copper, [latex]c=3.9\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{2}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J/kg}·\text{°}\text{C}[/latex].

Significance

If heat were released, the change in internal energy would be less and cause less of a temperature change than what was calculated in the problem.

Check Your Understanding

The quantities below represent four different transitions between the same initial and final state. Fill in the blanks.

| Q (J) | W (J) | [latex]\text{Δ}{E}_{\text{int}}\left(\text{J}\right)[/latex] |

|---|---|---|

| –80 | –120 | |

| 90 | ||

| 40 | ||

| –40 |

Show Solution

Line 1, [latex]\text{Δ}{E}_{\text{int}}=40\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J;}[/latex] line 2, [latex]W=50\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J}[/latex] and [latex]\text{Δ}{E}_{\text{int}}=40\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J;}[/latex] line 3, [latex]Q=80\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J}[/latex] and [latex]\text{Δ}{E}_{\text{int}}=40\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J;}[/latex] and line 4, [latex]Q=0[/latex] and [latex]\text{Δ}{E}_{\text{int}}=40\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J}[/latex]

Example

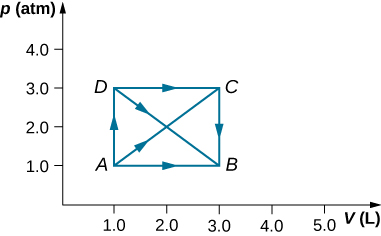

An Ideal Gas Making Transitions between Two States

Consider the quasi-static expansions of an ideal gas between the equilibrium states A and C of Figure 3.6. If 515 J of heat are added to the gas as it traverses the path ABC, how much heat is required for the transition along ADC? Assume that [latex]{p}_{1}=2.10\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{5}{\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{N/m}}^{2}\text{,}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{p}_{2}=1.05\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{5}{\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{N/m}}^{2}\text{,}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{V}_{1}=2.25\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-3}{\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{m}}^{3}\text{,}[/latex] and [latex]{V}_{2}=4.50\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-3}{\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{m}}^{3}.[/latex]

Strategy

The difference in work done between process ABC and process ADC is the area enclosed by ABCD. Because the change of the internal energy (a function of state) is the same for both processes, the difference in work is thus the same as the difference in heat transferred to the system.

Solution

Show Answer

For path ABC, the heat added is [latex]{Q}_{ABC}=515\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J}[/latex] and the work done by the gas is the area under the path on the pV diagram, which is

Along ADC, the work done by the gas is again the area under the path:

Then using the strategy we just described, we have

which leads to

Significance

The work calculations in this problem are made simple since no work is done along AD and BC and along AB and DC; the pressure is constant over the volume change, so the work done is simply [latex]p\text{Δ}V[/latex]. An isothermal line could also have been used, as we have derived the work for an isothermal process as [latex]W=nRT\text{ln}\frac{{V}_{2}}{{V}_{1}}[/latex].

Example

Isothermal Expansion of an Ideal Gas

Heat is added to 1 mol of an ideal monatomic gas confined to a cylinder with a movable piston at one end. The gas expands quasi-statically at a constant temperature of 300 K until its volume increases from V to 3V. (a) What is the change in internal energy of the gas? (b) How much work does the gas do? (c) How much heat is added to the gas?

Strategy

(a) Because the system is an ideal gas, the internal energy only changes when the temperature changes. (b) The heat added to the system is therefore purely used to do work that has been calculated in Work, Heat, and Internal Energy. (c) Lastly, the first law of thermodynamics can be used to calculate the heat added to the gas.

Solution

Show Answer

- We saw in the preceding section that the internal energy of an ideal monatomic gas is a function only of temperature. Since [latex]\text{Δ}T=0[/latex], for this process, [latex]\text{Δ}{E}_{\text{int}}=0.[/latex]

- The quasi-static isothermal expansion of an ideal gas was considered in the preceding section and was found to be

- With the results of parts (a) and (b), we can use the first law to determine the heat added:

which leads to

Significance

An isothermal process has no change in the internal energy. Based on that, the first law of thermodynamics reduces to [latex]Q=W[/latex].

Check Your Understanding

Why was it necessary to state that the process of Example 3.5 is quasi-static?

Show Solution

So that the process is represented by the curve [latex]p=nRT\text{/}V[/latex] on the pV plot for the evaluation of work.

Example

Vaporizing Water

When 1.00 g of water at [latex]100\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°}\text{C}[/latex] changes from the liquid to the gas phase at atmospheric pressure, its change in volume is [latex]1.67\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-3}{\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{m}}^{3}\text{.}[/latex] (a) How much heat must be added to vaporize the water? (b) How much work is done by the water against the atmosphere in its expansion? (c) What is the change in the internal energy of the water?

Strategy

We can first figure out how much heat is needed from the latent heat of vaporization of the water. From the volume change, we can calculate the work done from [latex]W=p\text{Δ}V[/latex] because the pressure is constant. Then, the first law of thermodynamics provides us with the change in the internal energy.

Solution

Show Answer

- With [latex]{L}_{v}[/latex] representing the latent heat of vaporization, the heat required to vaporize the water is

- Since the pressure on the system is constant at [latex]1.00\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{atm}=1.01\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{5}{\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{N/m}}^{2}[/latex], the work done by the water as it is vaporized is

- From the first law, the thermal energy of the water during its vaporization changes by

Significance

We note that in part (c), we see a change in internal energy, yet there is no change in temperature. Ideal gases that are not undergoing phase changes have the internal energy proportional to temperature. Internal energy in general is the sum of all energy in the system.

Check Your Understanding

When 1.00 g of ammonia boils at atmospheric pressure and [latex]-33.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°}\text{C,}[/latex] its volume changes from 1.47 to [latex]1130{\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{cm}}^{3}[/latex]. Its heat of vaporization at this pressure is [latex]1.37\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{6}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J/kg}\text{.}[/latex] What is the change in the internal energy of the ammonia when it vaporizes?

Show Solution

[latex]1.26\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{3}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J}\text{.}[/latex]

View this site to learn about the first law of thermodynamics. First, pump some heavy species molecules into the chamber. Then, play around by doing work (pushing the wall to the right where the person is located) to see how the internal energy changes (as seen by temperature). Then, look at how heat added changes the internal energy. Finally, you can set a parameter constant such as temperature and see what happens when you do work to keep the temperature constant (Note: You might see a change in these variables initially if you are moving around quickly in the simulation, but ultimately, this value will return to its equilibrium value).

Summary

- The internal energy of a thermodynamic system is a function of state and thus is unique for every equilibrium state of the system.

- The increase in the internal energy of the thermodynamic system is given by the heat added to the system less the work done by the system in any thermodynamics process.

Conceptual Questions

What does the first law of thermodynamics tell us about the energy of the universe?

Does adding heat to a system always increase its internal energy?

Show Solution

If more work is done on the system than heat added, the internal energy of the system will actually decrease.

A great deal of effort, time, and money has been spent in the quest for a so-called perpetual-motion machine, which is defined as a hypothetical machine that operates or produces useful work indefinitely and/or a hypothetical machine that produces more work or energy than it consumes. Explain, in terms of the first law of thermodynamics, why or why not such a machine is likely to be constructed.

Problems

When a dilute gas expands quasi-statically from 0.50 to 4.0 L, it does 250 J of work. Assuming that the gas temperature remains constant at 300 K, (a) what is the change in the internal energy of the gas? (b) How much heat is absorbed by the gas in this process?

In a quasi-static isobaric expansion, 500 J of work are done by the gas. The gas pressure is 0.80 atm and it was originally at 20.0 L. If the internal energy of the gas increased by 80 J in the expansion, how much heat does the gas absorb?

Show Solution

580 J

An ideal gas expands quasi-statically and isothermally from a state with pressure p and volume V to a state with volume 4V. How much heat is added to the expanding gas?

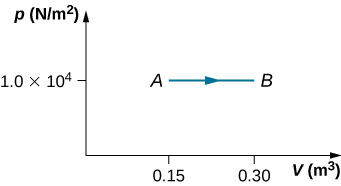

As shown below, if the heat absorbed by the gas along AB is 400 J, determine the quantities of heat absorbed along (a) ADB; (b) ACB; and (c) ADCB.

Show Solution

a. 600 J; b. 600 J; c. 800 J

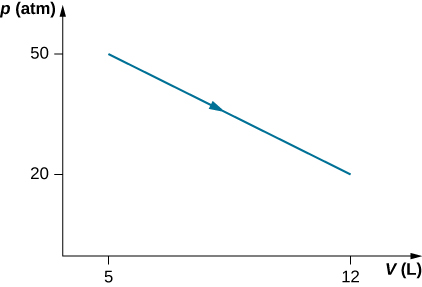

During the isobaric expansion from A to B represented below, 130 J of heat are removed from the gas. What is the change in its internal energy?

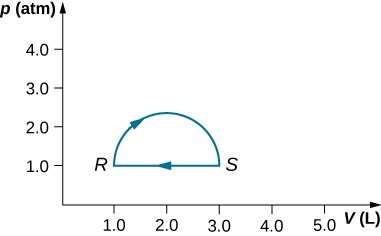

(a) What is the change in internal energy for the process represented by the closed path shown below? (b) How much heat is exchanged? (c) If the path is traversed in the opposite direction, how much heat is exchanged?

Show Solution

a. 0; b. 160 J; c. –160 J

When a gas expands along path AC shown below, it does 400 J of work and absorbs either 200 or 400 J of heat. (a) Suppose you are told that along path ABC, the gas absorbs either 200 or 400 J of heat. Which of these values is correct? (b) Give the correct answer from part (a), how much work is done by the gas along ABC? (c) Along CD, the internal energy of the gas decreases by 50 J. How much heat is exchanged by the gas along this path?

When a gas expands along AB (see below), it does 500 J of work and absorbs 250 J of heat. When the gas expands along AC, it does 700 J of work and absorbs 300 J of heat. (a) How much heat does the gas exchange along BC? (b) When the gas makes the transmission from C to A along CDA, 800 J of work are done on it from C to D. How much heat does it exchange along CDA?

Show Solution

a. –150 J; b. –400 J

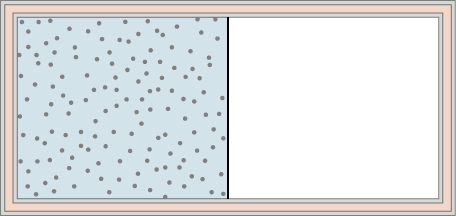

A dilute gas is stored in the left chamber of a container whose walls are perfectly insulating (see below), and the right chamber is evacuated. When the partition is removed, the gas expands and fills the entire container. Calculate the work done by the gas. Does the internal energy of the gas change in this process?

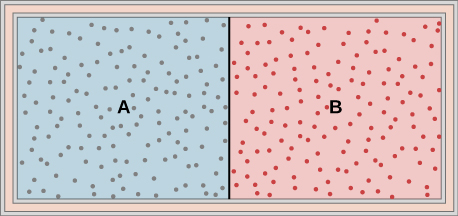

Ideal gases A and B are stored in the left and right chambers of an insulated container, as shown below. The partition is removed and the gases mix. Is any work done in this process? If the temperatures of A and B are initially equal, what happens to their common temperature after they are mixed?

Show Solution

No work is done and they reach the same common temperature.

An ideal monatomic gas at a pressure of [latex]2.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{5}{\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{N/m}}^{2}[/latex] and a temperature of 300 K undergoes a quasi-static isobaric expansion from [latex]2.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{3}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{to}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}4.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{3}{\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{cm}}^{3}.[/latex] (a) What is the work done by the gas? (b) What is the temperature of the gas after the expansion? (c) How many moles of gas are there? (d) What is the change in internal energy of the gas? (e) How much heat is added to the gas?

Consider the process for steam in a cylinder shown below. Suppose the change in the internal energy in this process is 30 kJ. Find the heat entering the system.

Show Solution

54,500 J

The state of 30 moles of steam in a cylinder is changed in a cyclic manner from a-b-c-a, where the pressure and volume of the states are: a (30 atm, 20 L), b (50 atm, 20 L), and c (50 atm, 45 L). Assume each change takes place along the line connecting the initial and final states in the pV plane. (a) Display the cycle in the pV plane. (b) Find the net work done by the steam in one cycle. (c) Find the net amount of heat flow in the steam over the course of one cycle.

A monatomic ideal gas undergoes a quasi-static process that is described by the function [latex]p\left(V\right)={p}_{1}+3\left(V-{V}_{1}\right)[/latex], where the starting state is [latex]\left({p}_{1},{V}_{1}\right)[/latex] and the final state [latex]\left({p}_{2},{V}_{2}\right)[/latex]. Assume the system consists of n moles of the gas in a container that can exchange heat with the environment and whose volume can change freely. (a) Evaluate the work done by the gas during the change in the state. (b) Find the change in internal energy of the gas. (c) Find the heat input to the gas during the change. (d) What are initial and final temperatures?

Show Solution

a. [latex]\left({p}_{1}+3{V}_{1}^{2}\right)\left({V}_{2}-{V}_{1}\right)-3{V}_{1}\left({V}_{2}^{2}-{V}_{1}^{2}\right)+\left({V}_{2}^{3}-{V}_{1}^{3}\right)[/latex]; b. [latex]\frac{3}{2}\left({p}_{2}{V}_{2}-{p}_{1}{V}_{1}\right)[/latex]; c. the sum of parts (a) and (b); d. [latex]{T}_{1}=\frac{{p}_{1}{V}_{1}}{nR}[/latex] and [latex]{T}_{2}=\frac{{p}_{2}{V}_{2}}{nR}[/latex]

A metallic container of fixed volume of [latex]2.5\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-3}{\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{m}}^{3}[/latex] immersed in a large tank of temperature [latex]27\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°}\text{C}[/latex] contains two compartments separated by a freely movable wall. Initially, the wall is kept in place by a stopper so that there are 0.02 mol of the nitrogen gas on one side and 0.03 mol of the oxygen gas on the other side, each occupying half the volume. When the stopper is removed, the wall moves and comes to a final position. The movement of the wall is controlled so that the wall moves in infinitesimal quasi-static steps. (a) Find the final volumes of the two sides assuming the ideal gas behavior for the two gases. (b) How much work does each gas do on the other? (c) What is the change in the internal energy of each gas? (d) Find the amount of heat that enters or leaves each gas.

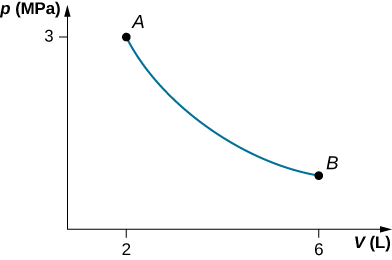

A gas in a cylindrical closed container is adiabatically and quasi-statically expanded from a state A (3 MPa, 2 L) to a state B with volume of 6 L along the path [latex]1.8\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}pV=\text{constant}\text{.}[/latex] (a) Plot the path in the pV plane. (b) Find the amount of work done by the gas and the change in the internal energy of the gas during the process.

Show Solution

a.

;

b. [latex]W=4.39\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{kJ,}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{Δ}{E}_{\text{int}}=-4.39\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{kJ}[/latex]

Glossary

- first law of thermodynamics

- the change in internal energy for any transition between two equilibrium states is [latex]\text{Δ}{E}_{\text{int}}=Q-W[/latex]

Licenses and Attributions

First Law of Thermodynamics. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-2/pages/3-3-first-law-of-thermodynamics. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-2/pages/1-introduction