Chapter 7. Electric Potential

7.4 Determining Field from Potential

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how to calculate the electric field in a system from the given potential

- Calculate the electric field in a given direction from a given potential

- Calculate the electric field throughout space from a given potential

Recall that we were able, in certain systems, to calculate the potential by integrating over the electric field. As you may already suspect, this means that we may calculate the electric field by taking derivatives of the potential, although going from a scalar to a vector quantity introduces some interesting wrinkles. We frequently need [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}[/latex] to calculate the force in a system; since it is often simpler to calculate the potential directly, there are systems in which it is useful to calculate V and then derive [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}[/latex] from it.

In general, regardless of whether the electric field is uniform, it points in the direction of decreasing potential, because the force on a positive charge is in the direction of [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}[/latex] and also in the direction of lower potential V. Furthermore, the magnitude of [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}[/latex] equals the rate of decrease of V with distance. The faster V decreases over distance, the greater the electric field. This gives us the following result.

Relationship between Voltage and Uniform Electric Field

In equation form, the relationship between voltage and uniform electric field is

where [latex]\text{Δ}s[/latex] is the distance over which the change in potential [latex]\text{Δ}V[/latex] takes place. The minus sign tells us that E points in the direction of decreasing potential. The electric field is said to be the gradient (as in grade or slope) of the electric potential.

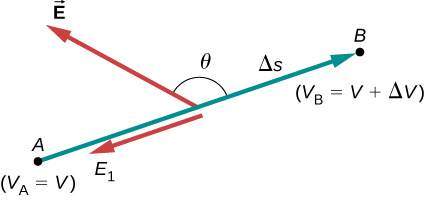

For continually changing potentials, [latex]\text{Δ}V[/latex] and [latex]\text{Δ}s[/latex] become infinitesimals, and we need differential calculus to determine the electric field. As shown in Figure 7.27, if we treat the distance [latex]\text{Δ}s[/latex] as very small so that the electric field is essentially constant over it, we find that

Therefore, the electric field components in the Cartesian directions are given by

This allows us to define the “grad” or “del” vector operator, which allows us to compute the gradient in one step. In Cartesian coordinates, it takes the form

With this notation, we can calculate the electric field from the potential with

a process we call calculating the gradient of the potential.

If we have a system with either cylindrical or spherical symmetry, we only need to use the del operator in the appropriate coordinates:

Example

Electric Field of a Point Charge

Calculate the electric field of a point charge from the potential.

Strategy

The potential is known to be [latex]V=k\frac{q}{r}[/latex], which has a spherical symmetry. Therefore, we use the spherical del operator in the formula [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}=\text{−}\stackrel{\to }{\nabla }V[/latex].

Solution

Show Answer

Performing this calculation gives us

This equation simplifies to

as expected.

Significance

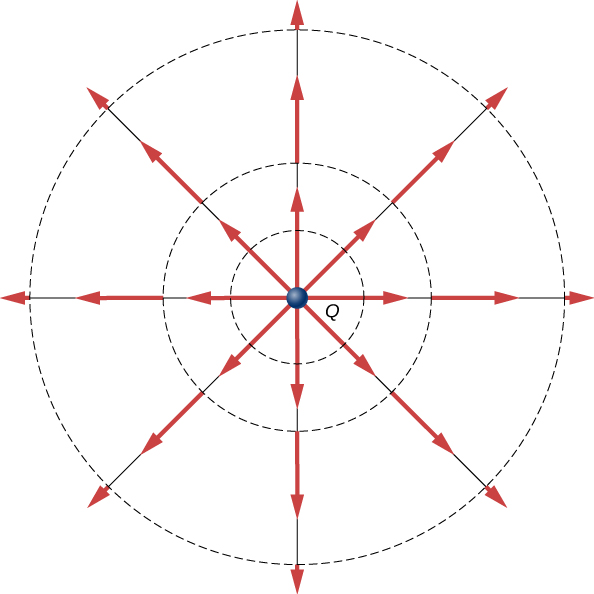

We not only obtained the equation for the electric field of a point particle that we’ve seen before, we also have a demonstration that [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}[/latex] points in the direction of decreasing potential, as shown in Figure 7.28.

Example

Electric Field of a Ring of Charge

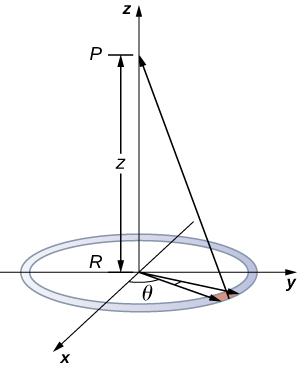

Use the potential found in Example 7.8 to calculate the electric field along the axis of a ring of charge (Figure 7.29).

Strategy

In this case, we are only interested in one dimension, the z-axis. Therefore, we use [latex]{E}_{z}=-\frac{\partial V}{\partial z}[/latex]

with the potential [latex]V=k\frac{{q}_{\text{tot}}}{\sqrt{{z}^{2}+{R}^{2}}}[/latex] found previously.

Solution

Show Answer

Taking the derivative of the potential yields

Significance

Again, this matches the equation for the electric field found previously. It also demonstrates a system in which using the full del operator is not necessary.

Check Your Understanding

Which coordinate system would you use to calculate the electric field of a dipole?

Show Solution

Any, but cylindrical is closest to the symmetry of a dipole.

Summary

- Just as we may integrate over the electric field to calculate the potential, we may take the derivative of the potential to calculate the electric field.

- This may be done for individual components of the electric field, or we may calculate the entire electric field vector with the gradient operator.

Conceptual Questions

If the electric field is zero throughout a region, must the electric potential also be zero in that region?

Show Solution

No. It will be constant, but not necessarily zero.

Explain why knowledge of [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}\left(x,y,z\right)[/latex] is not sufficient to determine V(x,y,z). What about the other way around?

Problems

Throughout a region, equipotential surfaces are given by [latex]z=\text{constant}[/latex]. The surfaces are equally spaced with [latex]V=100\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V}[/latex] for [latex]z=0.00\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{m,}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}V=200\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V}[/latex] for [latex]z=0.50\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{m,}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}V=300\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V}[/latex] for [latex]z=1.00\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{m.}[/latex] What is the electric field in this region?

Show Solution

The problem is describing a uniform field, so [latex]E=200\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V/m}[/latex] in the –z-direction.

In a particular region, the electric potential is given by [latex]V=\text{−}x{y}^{2}z+4xy.[/latex] What is the electric field in this region?

Calculate the electric field of an infinite line charge, throughout space.

Show Solution

Apply [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}=\text{−}\stackrel{\to }{\nabla }V[/latex] with [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\nabla }=\hat{\textbf{r}}\frac{\partial }{\partial r}+\hat{\pmb{\phi }}\frac{1}{r}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{\partial }{\partial \phi }+\hat{\textbf{z}}\frac{\partial }{\partial z}[/latex] to the potential calculated earlier,

[latex]V=-2k\lambda \text{ln}s:\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}=2k\lambda \frac{1}{r}\hat{\textbf{r}}[/latex] as expected.

Licenses and Attributions

Determining Field from Potential. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-2/pages/7-4-determining-field-from-potential. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-2/pages/1-introduction