Chapter 7. Electric Potential

7.2 Electric Potential and Potential Difference

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define electric potential, voltage, and potential difference

- Define the electron-volt

- Calculate electric potential and potential difference from potential energy and electric field

- Describe systems in which the electron-volt is a useful unit

- Apply conservation of energy to electric systems

Recall that earlier we defined electric field to be a quantity independent of the test charge in a given system, which would nonetheless allow us to calculate the force that would result on an arbitrary test charge. (The default assumption in the absence of other information is that the test charge is positive.) We briefly defined a field for gravity, but gravity is always attractive, whereas the electric force can be either attractive or repulsive. Therefore, although potential energy is perfectly adequate in a gravitational system, it is convenient to define a quantity that allows us to calculate the work on a charge independent of the magnitude of the charge. Calculating the work directly may be difficult, since [latex]W=\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{F}}·\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{d}}[/latex] and the direction and magnitude of [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{F}}[/latex] can be complex for multiple charges, for odd-shaped objects, and along arbitrary paths. But we do know that because [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{F}}=q\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}[/latex], the work, and hence [latex]\text{Δ}U,[/latex] is proportional to the test charge q. To have a physical quantity that is independent of test charge, we define electric potential V (or simply potential, since electric is understood) to be the potential energy per unit charge:

Electric Potential

The electric potential energy per unit charge is

Since U is proportional to q, the dependence on q cancels. Thus, V does not depend on q. The change in potential energy [latex]\text{Δ}U[/latex] is crucial, so we are concerned with the difference in potential or potential difference [latex]\text{Δ}V[/latex] between two points, where

Electric Potential Difference

The electric potential difference between points A and B, [latex]{V}_{B}-{V}_{A},[/latex] is defined to be the change in potential energy of a charge q moved from A to B, divided by the charge. Units of potential difference are joules per coulomb, given the name volt (V) after Alessandro Volta.

The familiar term voltage is the common name for electric potential difference. Keep in mind that whenever a voltage is quoted, it is understood to be the potential difference between two points. For example, every battery has two terminals, and its voltage is the potential difference between them. More fundamentally, the point you choose to be zero volts is arbitrary. This is analogous to the fact that gravitational potential energy has an arbitrary zero, such as sea level or perhaps a lecture hall floor. It is worthwhile to emphasize the distinction between potential difference and electrical potential energy.

Potential Difference and Electrical Potential Energy

The relationship between potential difference (or voltage) and electrical potential energy is given by

Voltage is not the same as energy. Voltage is the energy per unit charge. Thus, a motorcycle battery and a car battery can both have the same voltage (more precisely, the same potential difference between battery terminals), yet one stores much more energy than the other because [latex]\text{Δ}U=q\text{Δ}V.[/latex] The car battery can move more charge than the motorcycle battery, although both are 12-V batteries.

Example

Calculating Energy

You have a 12.0-V motorcycle battery that can move 5000 C of charge, and a 12.0-V car battery that can move 60,000 C of charge. How much energy does each deliver? (Assume that the numerical value of each charge is accurate to three significant figures.)

Strategy

To say we have a 12.0-V battery means that its terminals have a 12.0-V potential difference. When such a battery moves charge, it puts the charge through a potential difference of 12.0 V, and the charge is given a change in potential energy equal to [latex]\text{Δ}U=q\text{Δ}V.[/latex] To find the energy output, we multiply the charge moved by the potential difference.

Solution

Show Answer

For the motorcycle battery, [latex]q=5000\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{C}[/latex] and [latex]\text{Δ}V=12.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V}[/latex]. The total energy delivered by the motorcycle battery is

Similarly, for the car battery, [latex]q=60,000\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{C}[/latex] and

Significance

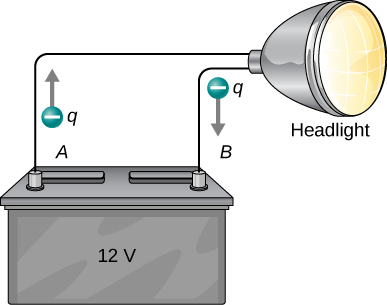

Voltage and energy are related, but they are not the same thing. The voltages of the batteries are identical, but the energy supplied by each is quite different. A car battery has a much larger engine to start than a motorcycle. Note also that as a battery is discharged, some of its energy is used internally and its terminal voltage drops, such as when headlights dim because of a depleted car battery. The energy supplied by the battery is still calculated as in this example, but not all of the energy is available for external use.

Check Your Understanding

How much energy does a 1.5-V AAA battery have that can move 100 C?

Show Solution

[latex]\text{Δ}U=q\text{Δ}V=\left(100\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{C}\right)\left(1.5\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V}\right)=150\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J}[/latex]

Note that the energies calculated in the previous example are absolute values. The change in potential energy for the battery is negative, since it loses energy. These batteries, like many electrical systems, actually move negative charge—electrons in particular. The batteries repel electrons from their negative terminals (A) through whatever circuitry is involved and attract them to their positive terminals (B), as shown in Figure 7.12. The change in potential is [latex]\text{Δ}V={V}_{B}-{V}_{A}=+12\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V}[/latex] and the charge q is negative, so that [latex]\text{Δ}U=q\text{Δ}V[/latex] is negative, meaning the potential energy of the battery has decreased when q has moved from A to B.

Example

How Many Electrons Move through a Headlight Each Second?

When a 12.0-V car battery powers a single 30.0-W headlight, how many electrons pass through it each second?

Strategy

To find the number of electrons, we must first find the charge that moves in 1.00 s. The charge moved is related to voltage and energy through the equations [latex]\text{Δ}U=q\text{Δ}V.[/latex] A 30.0-W lamp uses 30.0 joules per second. Since the battery loses energy, we have [latex]\text{Δ}U=-30\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J}[/latex] and, since the electrons are going from the negative terminal to the positive, we see that [latex]\text{Δ}V=\text{+12.0}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V}\text{.}[/latex]

Solution

Show Answer

To find the charge q moved, we solve the equation [latex]\text{Δ}U=q\text{Δ}V:[/latex]

Entering the values for [latex]\text{Δ}U[/latex] and [latex]\text{Δ}V[/latex], we get

The number of electrons [latex]{n}_{e}[/latex] is the total charge divided by the charge per electron. That is,

Significance

This is a very large number. It is no wonder that we do not ordinarily observe individual electrons with so many being present in ordinary systems. In fact, electricity had been in use for many decades before it was determined that the moving charges in many circumstances were negative. Positive charge moving in the opposite direction of negative charge often produces identical effects; this makes it difficult to determine which is moving or whether both are moving.

Check Your Understanding

How many electrons would go through a 24.0-W lamp?

Show Solution

–2.00 C, [latex]{n}_{e}=1.25\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{19}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{electrons}[/latex]

The Electron-Volt

The energy per electron is very small in macroscopic situations like that in the previous example—a tiny fraction of a joule. But on a submicroscopic scale, such energy per particle (electron, proton, or ion) can be of great importance. For example, even a tiny fraction of a joule can be great enough for these particles to destroy organic molecules and harm living tissue. The particle may do its damage by direct collision, or it may create harmful X-rays, which can also inflict damage. It is useful to have an energy unit related to submicroscopic effects.

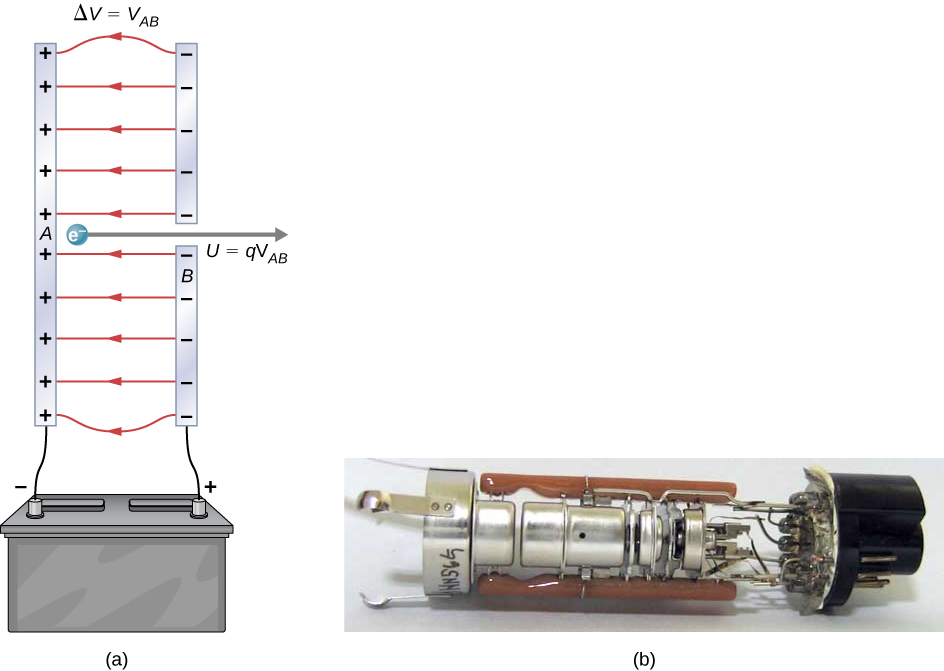

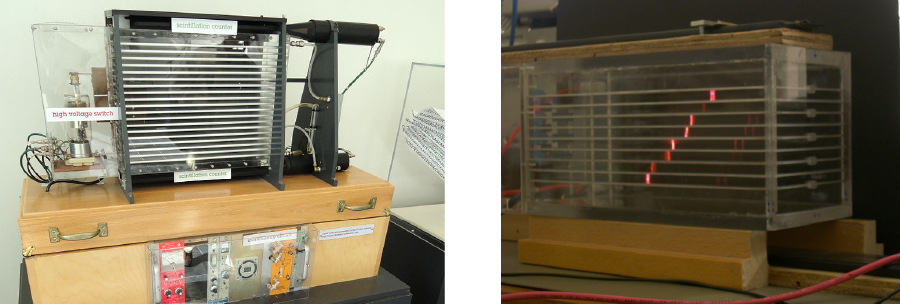

Figure 7.13 shows a situation related to the definition of such an energy unit. An electron is accelerated between two charged metal plates, as it might be in an old-model television tube or oscilloscope. The electron gains kinetic energy that is later converted into another form—light in the television tube, for example. (Note that in terms of energy, “downhill” for the electron is “uphill” for a positive charge.) Since energy is related to voltage by [latex]\text{Δ}U=q\text{Δ}V[/latex], we can think of the joule as a coulomb-volt.

Electron-Volt

On the submicroscopic scale, it is more convenient to define an energy unit called the electron-volt (eV), which is the energy given to a fundamental charge accelerated through a potential difference of 1 V. In equation form,

An electron accelerated through a potential difference of 1 V is given an energy of 1 eV. It follows that an electron accelerated through 50 V gains 50 eV. A potential difference of 100,000 V (100 kV) gives an electron an energy of 100,000 eV (100 keV), and so on. Similarly, an ion with a double positive charge accelerated through 100 V gains 200 eV of energy. These simple relationships between accelerating voltage and particle charges make the electron-volt a simple and convenient energy unit in such circumstances.

The electron-volt is commonly employed in submicroscopic processes—chemical valence energies and molecular and nuclear binding energies are among the quantities often expressed in electron-volts. For example, about 5 eV of energy is required to break up certain organic molecules. If a proton is accelerated from rest through a potential difference of 30 kV, it acquires an energy of 30 keV (30,000 eV) and can break up as many as 6000 of these molecules [latex]\left(30,000\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{eV}÷5\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{eV}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{per molecule}=6000\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{molecules}\right).[/latex] Nuclear decay energies are on the order of 1 MeV (1,000,000 eV) per event and can thus produce significant biological damage.

Conservation of Energy

The total energy of a system is conserved if there is no net addition (or subtraction) due to work or heat transfer. For conservative forces, such as the electrostatic force, conservation of energy states that mechanical energy is a constant.

Mechanical energy is the sum of the kinetic energy and potential energy of a system; that is, [latex]K+U=\text{constant}\text{.}[/latex] A loss of U for a charged particle becomes an increase in its K. Conservation of energy is stated in equation form as

or

where i and f stand for initial and final conditions. As we have found many times before, considering energy can give us insights and facilitate problem solving.

Example

Electrical Potential Energy Converted into Kinetic Energy

Calculate the final speed of a free electron accelerated from rest through a potential difference of 100 V. (Assume that this numerical value is accurate to three significant figures.)

Strategy

We have a system with only conservative forces. Assuming the electron is accelerated in a vacuum, and neglecting the gravitational force (we will check on this assumption later), all of the electrical potential energy is converted into kinetic energy. We can identify the initial and final forms of energy to be [latex]{K}_{\text{i}}=0,{K}_{\text{f}}=\frac{1}{2}m{v}^{2},{U}_{\text{i}}=qV,{U}_{\text{f}}=0.[/latex]

Solution

Show Answer

Conservation of energy states that

Entering the forms identified above, we obtain

We solve this for v:

Entering values for q, V, and m gives

Significance

Note that both the charge and the initial voltage are negative, as in Figure 7.13. From the discussion of electric charge and electric field, we know that electrostatic forces on small particles are generally very large compared with the gravitational force. The large final speed confirms that the gravitational force is indeed negligible here. The large speed also indicates how easy it is to accelerate electrons with small voltages because of their very small mass. Voltages much higher than the 100 V in this problem are typically used in electron guns. These higher voltages produce electron speeds so great that effects from special relativity must be taken into account and hence are reserved for a later chapter (Relativity). That is why we consider a low voltage (accurately) in this example.

Check Your Understanding

How would this example change with a positron? A positron is identical to an electron except the charge is positive.

Show Solution

It would be going in the opposite direction, with no effect on the calculations as presented.

Voltage and Electric Field

So far, we have explored the relationship between voltage and energy. Now we want to explore the relationship between voltage and electric field. We will start with the general case for a non-uniform [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}[/latex] field. Recall that our general formula for the potential energy of a test charge q at point P relative to reference point R is

When we substitute in the definition of electric field [latex]\left(\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}=\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{F}}\text{/}q\right),[/latex] this becomes

Applying our definition of potential [latex]\left(V=U\text{/}q\right)[/latex] to this potential energy, we find that, in general,

From our previous discussion of the potential energy of a charge in an electric field, the result is independent of the path chosen, and hence we can pick the integral path that is most convenient.

Consider the special case of a positive point charge q at the origin. To calculate the potential caused by q at a distance r from the origin relative to a reference of 0 at infinity (recall that we did the same for potential energy), let [latex]P=r[/latex] and [latex]R=\infty ,[/latex] with [latex]d\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{l}}=d\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{r}}=\hat{\textbf{r}}dr[/latex] and use [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}=\frac{kq}{{r}^{2}}\hat{\textbf{r}}.[/latex] When we evaluate the integral

for this system, we have

which simplifies to

This result,

is the standard form of the potential of a point charge. This will be explored further in the next section.

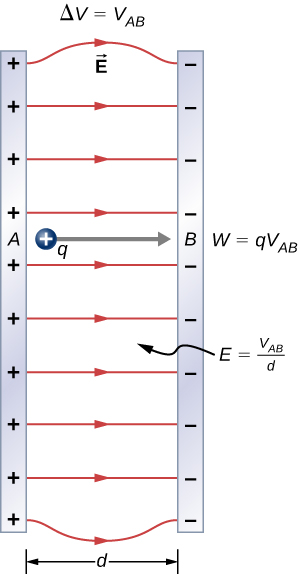

To examine another interesting special case, suppose a uniform electric field [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}[/latex] is produced by placing a potential difference (or voltage) [latex]\text{Δ}V[/latex] across two parallel metal plates, labeled A and B (Figure 7.14). Examining this situation will tell us what voltage is needed to produce a certain electric field strength. It will also reveal a more fundamental relationship between electric potential and electric field.

From a physicist’s point of view, either [latex]\text{Δ}V[/latex] or [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}[/latex] can be used to describe any interaction between charges. However, [latex]\text{Δ}V[/latex] is a scalar quantity and has no direction, whereas [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}[/latex] is a vector quantity, having both magnitude and direction. (Note that the magnitude of the electric field, a scalar quantity, is represented by E.) The relationship between [latex]\text{Δ}V[/latex] and [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}[/latex] is revealed by calculating the work done by the electric force in moving a charge from point A to point B. But, as noted earlier, arbitrary charge distributions require calculus. We therefore look at a uniform electric field as an interesting special case.

The work done by the electric field in Figure 7.14 to move a positive charge q from A, the positive plate, higher potential, to B, the negative plate, lower potential, is

The potential difference between points A and B is

Entering this into the expression for work yields

Work is [latex]W=\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{F}}·\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{d}}=Fd\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{cos}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\theta[/latex]; here [latex]\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{cos}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\theta =1[/latex], since the path is parallel to the field. Thus, [latex]W=Fd[/latex]. Since [latex]F=qE[/latex], we see that [latex]W=qEd[/latex].

Substituting this expression for work into the previous equation gives

The charge cancels, so we obtain for the voltage between points A and B

where d is the distance from A to B, or the distance between the plates in Figure 7.14. Note that this equation implies that the units for electric field are volts per meter. We already know the units for electric field are newtons per coulomb; thus, the following relation among units is valid:

Furthermore, we may extend this to the integral form. Substituting Equation 7.5 into our definition for the potential difference between points A and B, we obtain

which simplifies to

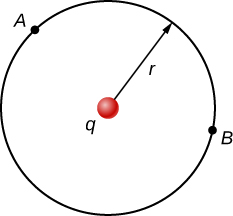

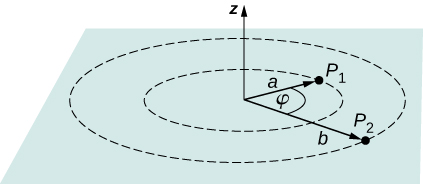

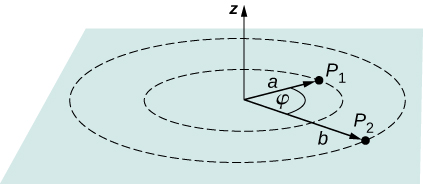

As a demonstration, from this we may calculate the potential difference between two points (A and B) equidistant from a point charge q at the origin, as shown in Figure 7.15.

To do this, we integrate around an arc of the circle of constant radius r between A and B, which means we let [latex]d\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{l}}=r\hat{\pmb{\phi }}d\phi ,[/latex] while using [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}=\frac{kq}{{r}^{2}}\hat{\textbf{r}}[/latex]. Thus,

for this system becomes

However, [latex]\hat{\textbf{r}}·\hat{\pmb{\phi }}=0[/latex] and therefore

This result, that there is no difference in potential along a constant radius from a point charge, will come in handy when we map potentials.

Example

What Is the Highest Voltage Possible between Two Plates?

Dry air can support a maximum electric field strength of about [latex]3.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{6}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V/m}\text{.}[/latex] Above that value, the field creates enough ionization in the air to make the air a conductor. This allows a discharge or spark that reduces the field. What, then, is the maximum voltage between two parallel conducting plates separated by 2.5 cm of dry air?

Strategy

We are given the maximum electric field E between the plates and the distance d between them. We can use the equation [latex]{V}_{AB}=Ed[/latex] to calculate the maximum voltage.

Solution

Show Answer

The potential difference or voltage between the plates is

Entering the given values for E and d gives

or

(The answer is quoted to only two digits, since the maximum field strength is approximate.)

Significance

One of the implications of this result is that it takes about 75 kV to make a spark jump across a 2.5-cm (1-in.) gap, or 150 kV for a 5-cm spark. This limits the voltages that can exist between conductors, perhaps on a power transmission line. A smaller voltage can cause a spark if there are spines on the surface, since sharp points have larger field strengths than smooth surfaces. Humid air breaks down at a lower field strength, meaning that a smaller voltage will make a spark jump through humid air. The largest voltages can be built up with static electricity on dry days (Figure 7.16).

Example

Field and Force inside an Electron Gun

An electron gun (Figure 7.13) has parallel plates separated by 4.00 cm and gives electrons 25.0 keV of energy. (a) What is the electric field strength between the plates? (b) What force would this field exert on a piece of plastic with a [latex]0.500\text{-}\mu \text{C}[/latex] charge that gets between the plates?

Strategy

Since the voltage and plate separation are given, the electric field strength can be calculated directly from the expression [latex]E=\frac{{V}_{AB}}{d}[/latex]. Once we know the electric field strength, we can find the force on a charge by using [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{F}}=q\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}.[/latex] Since the electric field is in only one direction, we can write this equation in terms of the magnitudes, [latex]F=qE[/latex].

Solution

Show Answer

- The expression for the magnitude of the electric field between two uniform metal plates is

[latex]E=\frac{{V}_{AB}}{d}.[/latex]

Since the electron is a single charge and is given 25.0 keV of energy, the potential difference must be 25.0 kV. Entering this value for [latex]{V}_{AB}[/latex] and the plate separation of 0.0400 m, we obtain

[latex]E=\frac{25.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{kV}}{0.0400\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{m}}=6.25\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{5}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V/m}\text{.}[/latex] - The magnitude of the force on a charge in an electric field is obtained from the equation

[latex]F=qE.[/latex]

Substituting known values gives

[latex]F=\left(0.500\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-6}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{C}\right)\left(6.25\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{5}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V/m}\right)=0.313\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{N}\text{.}[/latex]

Significance

Note that the units are newtons, since [latex]1\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V/m}=1\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{N/C}[/latex]. Because the electric field is uniform between the plates, the force on the charge is the same no matter where the charge is located between the plates.

Example

Calculating Potential of a Point Charge

Given a point charge [latex]q=+2.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{nC}[/latex] at the origin, calculate the potential difference between point [latex]{P}_{1}[/latex] a distance [latex]a=4.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{cm}[/latex] from q, and [latex]{P}_{2}[/latex] a distance [latex]b=12.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{cm}[/latex] from q, where the two points have an angle of [latex]\phi =24\text{°}[/latex] between them (Figure 7.17).

Strategy

Do this in two steps. The first step is to use [latex]{V}_{B}-{V}_{A}=\text{−}{\int }_{A}^{B}\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}·d\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{l}}[/latex] and let [latex]A=a=4.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{cm}[/latex] and [latex]B=b=12.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{cm},[/latex] with [latex]d\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{l}}=d\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{r}}=\hat{\textbf{r}}dr[/latex] and [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}=\frac{kq}{{r}^{2}}\hat{\textbf{r}}.[/latex] Then perform the integral. The second step is to integrate [latex]{V}_{B}-{V}_{A}=\text{−}{\int }_{A}^{B}\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}·d\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{l}}[/latex] around an arc of constant radius r, which means we let [latex]d\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{l}}=r\hat{\pmb{\phi }}d\phi[/latex] with limits [latex]0\le \phi \le 24\text{°},[/latex] still using [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}=\frac{kq}{{r}^{2}}\hat{\textbf{r}}[/latex]. Then add the two results together.

Solution

Show Answer

For the first part, [latex]{V}_{B}-{V}_{A}=\text{−}{\int }_{A}^{B}\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}·d\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{l}}[/latex] for this system becomes [latex]{V}_{b}-{V}_{a}=\text{−}{\int }_{a}^{b}\frac{kq}{{r}^{2}}\hat{\textbf{r}}·\hat{\textbf{r}}dr[/latex] which computes to

For the second step, [latex]{V}_{B}-{V}_{A}=\text{−}{\int }_{A}^{B}\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{E}}·d\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{l}}[/latex] becomes [latex]\text{Δ}V=\text{−}{\int }_{0}^{24\text{°}}\frac{kq}{{r}^{2}}\hat{\textbf{r}}·r\hat{\pmb{\phi }}d\phi[/latex], but [latex]\hat{\textbf{r}}·\hat{\pmb{\phi }}=0[/latex] and therefore [latex]\text{Δ}V=0.[/latex] Adding the two parts together, we get 300 V.

Significance

We have demonstrated the use of the integral form of the potential difference to obtain a numerical result. Notice that, in this particular system, we could have also used the formula for the potential due to a point charge at the two points and simply taken the difference.

Check Your Understanding

From the examples, how does the energy of a lightning strike vary with the height of the clouds from the ground? Consider the cloud-ground system to be two parallel plates.

Show Solution

Given a fixed maximum electric field strength, the potential at which a strike occurs increases with increasing height above the ground. Hence, each electron will carry more energy. Determining if there is an effect on the total number of electrons lies in the future.

Before presenting problems involving electrostatics, we suggest a problem-solving strategy to follow for this topic.

Problem-Solving Strategy: Electrostatics

- Examine the situation to determine if static electricity is involved; this may concern separated stationary charges, the forces among them, and the electric fields they create.

- Identify the system of interest. This includes noting the number, locations, and types of charges involved.

- Identify exactly what needs to be determined in the problem (identify the unknowns). A written list is useful. Determine whether the Coulomb force is to be considered directly—if so, it may be useful to draw a free-body diagram, using electric field lines.

- Make a list of what is given or can be inferred from the problem as stated (identify the knowns). It is important to distinguish the Coulomb force F from the electric field E, for example.

- Solve the appropriate equation for the quantity to be determined (the unknown) or draw the field lines as requested.

- Examine the answer to see if it is reasonable: Does it make sense? Are units correct and the numbers involved reasonable?

Summary

- Electric potential is potential energy per unit charge.

- The potential difference between points A and B, [latex]{V}_{B}-{V}_{A},[/latex] that is, the change in potential of a charge q moved from A to B, is equal to the change in potential energy divided by the charge.

- Potential difference is commonly called voltage, represented by the symbol [latex]\text{Δ}V[/latex]:

[latex]\text{Δ}V=\frac{\text{Δ}U}{q}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{or}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{Δ}U=q\text{Δ}V.[/latex] - An electron-volt is the energy given to a fundamental charge accelerated through a potential difference of 1 V. In equation form,

[latex]1\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{eV}=\left(1.60\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-19}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{C}\right)\left(1\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V}\right)=\left(1.60\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}10}^{-19}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{C}\right)\left(1\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J/C}\right)=1.60\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-19}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J}\text{.}[/latex]

Conceptual Questions

Discuss how potential difference and electric field strength are related. Give an example.

What is the strength of the electric field in a region where the electric potential is constant?

Show Solution

The electric field strength is zero because electric potential differences are directly related to the field strength. If the potential difference is zero, then the field strength must also be zero.

If a proton is released from rest in an electric field, will it move in the direction of increasing or decreasing potential? Also answer this question for an electron and a neutron. Explain why.

Voltage is the common word for potential difference. Which term is more descriptive, voltage or potential difference?

Show Solution

Potential difference is more descriptive because it indicates that it is the difference between the electric potential of two points.

If the voltage between two points is zero, can a test charge be moved between them with zero net work being done? Can this necessarily be done without exerting a force? Explain.

What is the relationship between voltage and energy? More precisely, what is the relationship between potential difference and electric potential energy?

Show Solution

They are very similar, but potential difference is a feature of the system; when a charge is introduced to the system, it will have a potential energy which may be calculated by multiplying the magnitude of the charge by the potential difference.

Voltages are always measured between two points. Why?

How are units of volts and electron-volts related? How do they differ?

Show Solution

An electron-volt is a volt multiplied by the charge of an electron. Volts measure potential difference, electron-volts are a unit of energy.

Can a particle move in a direction of increasing electric potential, yet have its electric potential energy decrease? Explain

Problems

Find the ratio of speeds of an electron and a negative hydrogen ion (one having an extra electron) accelerated through the same voltage, assuming non-relativistic final speeds. Take the mass of the hydrogen ion to be [latex]1.67\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-27}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{kg}\text{.}[/latex]

Show Solution

[latex]\begin{array}{ccc}\frac{1}{2}{m}_{e}{v}_{e}^{2}\hfill & =\hfill & qV,\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{1}{2}{m}_{\text{H}}{v}_{\text{H}}^{2}=qV,\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{so that}\hfill \\ \frac{{m}_{e}{v}_{e}^{2}}{{m}_{\text{H}}{v}_{\text{H}}^{2}}\hfill & =\hfill & 1\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{or}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\frac{{v}_{e}}{{v}_{\text{H}}}=42.8\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

An evacuated tube uses an accelerating voltage of 40 kV to accelerate electrons to hit a copper plate and produce X-rays. Non-relativistically, what would be the maximum speed of these electrons?

Show that units of V/m and N/C for electric field strength are indeed equivalent.

Show Solution

[latex]1\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V}=1\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J/C;}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}1\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J}=1\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{N}·\text{m}\to 1\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V/m}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}=1\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{N/C}[/latex]

What is the strength of the electric field between two parallel conducting plates separated by 1.00 cm and having a potential difference (voltage) between them of [latex]1.50\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{4}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V}[/latex]?

The electric field strength between two parallel conducting plates separated by 4.00 cm is [latex]7.50\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{4}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V/m}[/latex]. (a) What is the potential difference between the plates? (b) The plate with the lowest potential is taken to be zero volts. What is the potential 1.00 cm from that plate and 3.00 cm from the other?

Show Solution

a. [latex]{V}_{AB}=3.00\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{kV}[/latex]; b. [latex]{V}_{AB}=750\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V}[/latex]

The voltage across a membrane forming a cell wall is 80.0 mV and the membrane is 9.00 nm thick. What is the electric field strength? (The value is surprisingly large, but correct.) You may assume a uniform electric field.

Two parallel conducting plates are separated by 10.0 cm, and one of them is taken to be at zero volts. (a) What is the electric field strength between them, if the potential 8.00 cm from the zero volt plate (and 2.00 cm from the other) is 450 V? (b) What is the voltage between the plates?

Show Solution

a. [latex]{V}_{AB}=Ed\to E=5.63\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{kV/m}[/latex];

b. [latex]{V}_{AB}=563\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V}[/latex]

Find the maximum potential difference between two parallel conducting plates separated by 0.500 cm of air, given the maximum sustainable electric field strength in air to be [latex]3.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{6}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V/m}[/latex].

An electron is to be accelerated in a uniform electric field having a strength of [latex]2.00\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{6}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V/m}\text{.}[/latex] (a) What energy in keV is given to the electron if it is accelerated through 0.400 m? (b) Over what distance would it have to be accelerated to increase its energy by 50.0 GeV?

Show Solution

a. [latex]\begin{array}{ccc}\text{Δ}K\hfill & =\hfill & q\text{Δ}V\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{and}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{V}_{AB}=Ed,\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{so that}\hfill \\ \text{Δ}K\hfill & =\hfill & 800\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{keV;}\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

b. [latex]d=25.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{km}[/latex]

Use the definition of potential difference in terms of electric field to deduce the formula for potential difference between [latex]r={r}_{a}[/latex] and [latex]r={r}_{b}[/latex] for a point charge located at the origin. Here r is the spherical radial coordinate.

The electric field in a region is pointed away from the z-axis and the magnitude depends upon the distance s from the axis. The magnitude of the electric field is given as [latex]E=\frac{\alpha }{s}[/latex] where [latex]\alpha[/latex] is a constant. Find the potential difference between points [latex]{P}_{1}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{and}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{P}_{2}[/latex], explicitly stating the path over which you conduct the integration for the line integral.

Show Solution

One possibility is to stay at constant radius and go along the arc from [latex]{P}_{1}[/latex] to [latex]{P}_{2}[/latex], which will have zero potential due to the path being perpendicular to the electric field. Then integrate from a to b: [latex]{V}_{ab}=\alpha \phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{ln}\left(\frac{b}{a}\right)[/latex]

Singly charged gas ions are accelerated from rest through a voltage of 13.0 V. At what temperature will the average kinetic energy of gas molecules be the same as that given these ions?

Glossary

- electric potential

- potential energy per unit charge

- electric potential difference

- the change in potential energy of a charge q moved between two points, divided by the charge.

- electron-volt

- energy given to a fundamental charge accelerated through a potential difference of one volt

- voltage

- change in potential energy of a charge moved from one point to another, divided by the charge; units of potential difference are joules per coulomb, known as volt

Licenses and Attributions

Electric Potential and Potential Difference. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-2/pages/7-2-electric-potential-and-potential-difference. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-2/pages/1-introduction