Chapter 13. Electromagnetic Induction

13.2 Lenz’s Law

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Use Lenz’s law to determine the direction of induced emf whenever a magnetic flux changes

- Use Faraday’s law with Lenz’s law to determine the induced emf in a coil and in a solenoid

The direction in which the induced emf drives current around a wire loop can be found through the negative sign. However, it is usually easier to determine this direction with Lenz’s law, named in honor of its discoverer, Heinrich Lenz (1804–1865). (Faraday also discovered this law, independently of Lenz.) We state Lenz’s law as follows:

Lenz’s Law

The direction of the induced emf drives current around a wire loop to always oppose the change in magnetic flux that causes the emf.

Lenz’s law can also be considered in terms of conservation of energy. If pushing a magnet into a coil causes current, the energy in that current must have come from somewhere. If the induced current causes a magnetic field opposing the increase in field of the magnet we pushed in, then the situation is clear. We pushed a magnet against a field and did work on the system, and that showed up as current. If it were not the case that the induced field opposes the change in the flux, the magnet would be pulled in produce a current without anything having done work. Electric potential energy would have been created, violating the conservation of energy.

To determine an induced emf [latex]\epsilon[/latex], you first calculate the magnetic flux [latex]{\text{Φ}}_{\text{m}}[/latex] and then obtain [latex]d{\text{Φ}}_{\text{m}}\text{/}dt.[/latex] The magnitude of [latex]\epsilon[/latex] is given by [latex]\epsilon =|d{\text{Φ}}_{\text{m}}\text{/}dt|.[/latex] Finally, you can apply Lenz’s law to determine the sense of [latex]\text{ε}[/latex]. This will be developed through examples that illustrate the following problem-solving strategy.

Problem-Solving Strategy: Lenz’s Law

To use Lenz’s law to determine the directions of induced magnetic fields, currents, and emfs:

- Make a sketch of the situation for use in visualizing and recording directions.

- Determine the direction of the applied magnetic field [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{B}}.[/latex]

- Determine whether its magnetic flux is increasing or decreasing.

- Now determine the direction of the induced magnetic field [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{B}}.[/latex] The induced magnetic field tries to reinforce a magnetic flux that is decreasing or opposes a magnetic flux that is increasing. Therefore, the induced magnetic field adds or subtracts to the applied magnetic field, depending on the change in magnetic flux.

- Use right-hand rule 2 (RHR-2; see Magnetic Forces and Fields) to determine the direction of the induced current I that is responsible for the induced magnetic field [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{B}}.[/latex]

- The direction (or polarity) of the induced emf can now drive a conventional current in this direction.

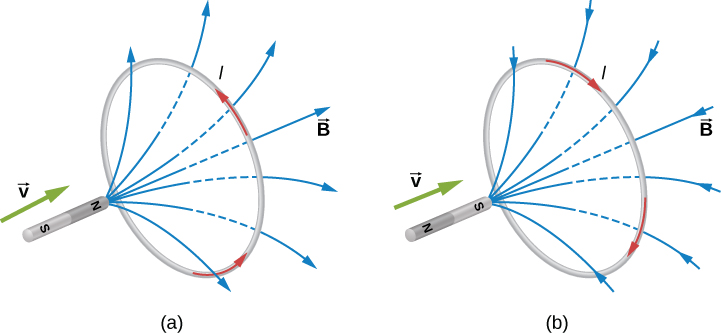

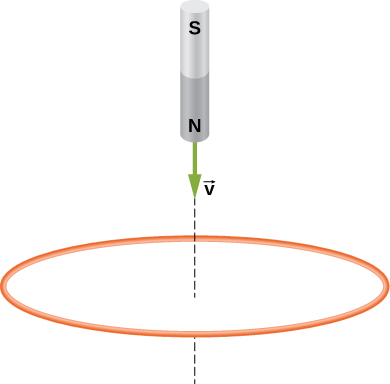

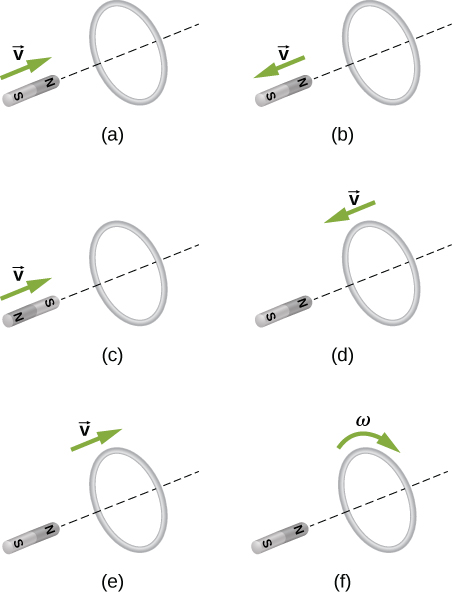

Let’s apply Lenz’s law to the system of Figure 13.7(a). We designate the “front” of the closed conducting loop as the region containing the approaching bar magnet, and the “back” of the loop as the other region. As the north pole of the magnet moves toward the loop, the flux through the loop due to the field of the magnet increases because the strength of field lines directed from the front to the back of the loop is increasing. A current is therefore induced in the loop. By Lenz’s law, the direction of the induced current must be such that its own magnetic field is directed in a way to oppose the changing flux caused by the field of the approaching magnet. Hence, the induced current circulates so that its magnetic field lines through the loop are directed from the back to the front of the loop. By RHR-2, place your thumb pointing against the magnetic field lines, which is toward the bar magnet. Your fingers wrap in a counterclockwise direction as viewed from the bar magnet. Alternatively, we can determine the direction of the induced current by treating the current loop as an electromagnet that opposes the approach of the north pole of the bar magnet. This occurs when the induced current flows as shown, for then the face of the loop nearer the approaching magnet is also a north pole.

Part (b) of the figure shows the south pole of a magnet moving toward a conducting loop. In this case, the flux through the loop due to the field of the magnet increases because the number of field lines directed from the back to the front of the loop is increasing. To oppose this change, a current is induced in the loop whose field lines through the loop are directed from the front to the back. Equivalently, we can say that the current flows in a direction so that the face of the loop nearer the approaching magnet is a south pole, which then repels the approaching south pole of the magnet. By RHR-2, your thumb points away from the bar magnet. Your fingers wrap in a clockwise fashion, which is the direction of the induced current.

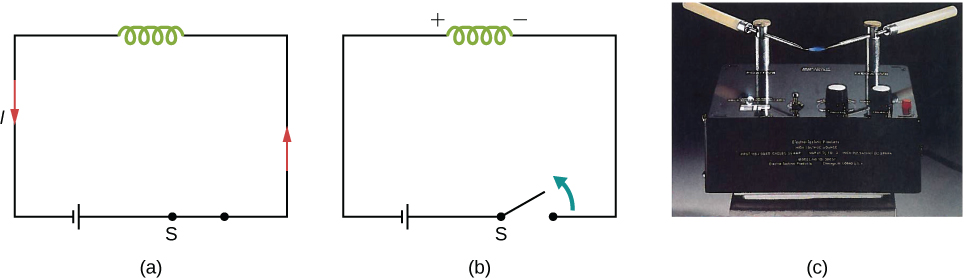

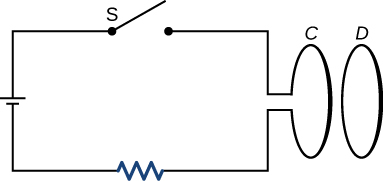

Another example illustrating the use of Lenz’s law is shown in Figure 13.8. When the switch is opened, the decrease in current through the solenoid causes a decrease in magnetic flux through its coils, which induces an emf in the solenoid. This emf must oppose the change (the termination of the current) causing it. Consequently, the induced emf has the polarity shown and drives in the direction of the original current. This may generate an arc across the terminals of the switch as it is opened.

Check Your Understanding

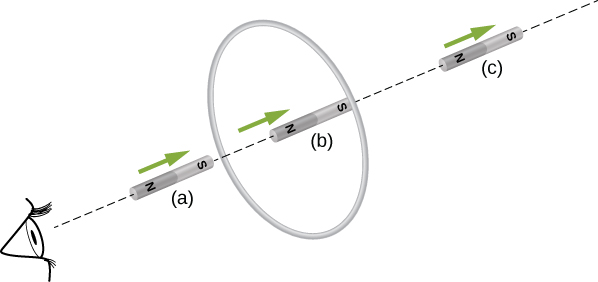

Find the direction of the induced current in the wire loop shown below as the magnet enters, passes through, and leaves the loop.

Show Solution

To the observer shown, the current flows clockwise as the magnet approaches, decreases to zero when the magnet is centered in the plane of the coil, and then flows counterclockwise as the magnet leaves the coil.

Check Your Understanding

Verify the directions of the induced currents in Figure 13.3.

Example

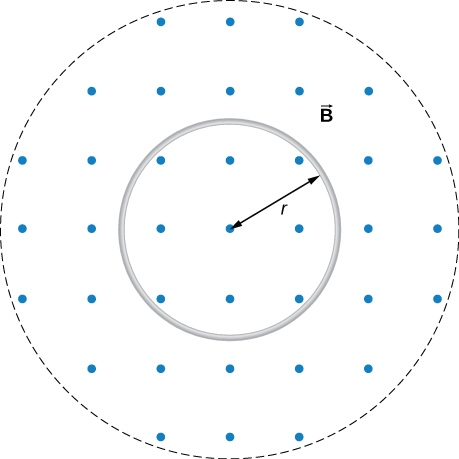

A Circular Coil in a Changing Magnetic Field

A magnetic field [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{B}}[/latex] is directed outward perpendicular to the plane of a circular coil of radius [latex]r=0.50\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{m}[/latex] (Figure 13.9). The field is cylindrically symmetrical with respect to the center of the coil, and its magnitude decays exponentially according to [latex]B=\left(1.5T\right){e}^{\text{−}\left(5.0{\text{s}}^{-1}\right)t},[/latex] where B is in teslas and t is in seconds. (a) Calculate the emf induced in the coil at the times [latex]{t}_{1}=0,[/latex] [latex]{t}_{2}=5.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}1{0}^{\text{−}2}\text{s},[/latex] and [latex]{t}_{3}=1.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{s}.[/latex] (b) Determine the current in the coil at these three times if its resistance is [latex]10\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{Ω}.[/latex]

Strategy

Since the magnetic field is perpendicular to the plane of the coil and constant over each spot in the coil, the dot product of the magnetic field [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{B}}[/latex] and normal to the area unit vector [latex]\hat{\textbf{n}}[/latex] turns into a multiplication. The magnetic field can be pulled out of the integration, leaving the flux as the product of the magnetic field times area. We need to take the time derivative of the exponential function to calculate the emf using Faraday’s law. Then we use Ohm’s law to calculate the current.

Solution

Show Answer

- Since [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{B}}[/latex] is perpendicular to the plane of the coil, the magnetic flux is given by

[latex]\begin{array}{}\\ \\ \hfill {\text{Φ}}_{\text{m}}& =B\pi {r}^{2}=\left(1.5{e}^{-5.0t}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{T}\right)\pi {\left(0.50\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{m}\right)}^{2}\hfill \\ & =1.2{e}^{\text{−}\left(5.0{\text{s}}^{-1}\right)t}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{Wb}\text{.}\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

From Faraday’s law, the magnitude of the induced emf is

[latex]\epsilon =|\frac{d{\text{Φ}}_{m}}{dt}|=|\frac{d}{dt}\left(1.2{e}^{\text{−}\left(5.0{\text{s}}^{-1}\right)t}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{Wb}\right)|=6.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{e}^{\text{−}\left(5.0{\text{s}}^{-1}\right)t}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V}\text{.}[/latex]

Since [latex]\stackrel{\to }{\textbf{B}}[/latex] is directed out of the page and is decreasing, the induced current must flow counterclockwise when viewed from above so that the magnetic field it produces through the coil also points out of the page. For all three times, the sense of ε is counterclockwise; its magnitudes are

[latex]\epsilon \left({t}_{1}\right)=6.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V};\phantom{\rule{0.5em}{0ex}}\epsilon \left({t}_{2}\right)=4.7\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V};\phantom{\rule{0.5em}{0ex}}\epsilon \left({t}_{3}\right)=0.040\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V}.[/latex] - From Ohm’s law, the respective currents are

[latex]\begin{array}{ccc}\hfill I\left({t}_{1}\right)& =\hfill & \frac{\epsilon \left({t}_{1}\right)}{R}=\frac{6.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V}}{10\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{Ω}}=0.60\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{A;}\hfill \\ \hfill I\left({t}_{2}\right)& =\hfill & \frac{4.7\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V}}{10\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{Ω}}=0.47\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{A;}\hfill \end{array}[/latex]

and

[latex]I\left({t}_{3}\right)=\frac{0.040\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{V}}{10\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{Ω}}=4.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-3}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{A}\text{.}[/latex]

Significance

An emf voltage is created by a changing magnetic flux over time. If we know how the magnetic field varies with time over a constant area, we can take its time derivative to calculate the induced emf.

Example

Changing Magnetic Field Inside a Solenoid

The current through the windings of a solenoid with [latex]n=2000[/latex] turns per meter is changing at a rate [latex]dI\text{/}dt=3.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{A}\text{/}\text{s}.[/latex] (See Sources of Magnetic Fields for a discussion of solenoids.) The solenoid is 50-cm long and has a cross-sectional diameter of 3.0 cm. A small coil consisting of [latex]N=20[/latex] closely wound turns wrapped in a circle of diameter 1.0 cm is placed in the middle of the solenoid such that the plane of the coil is perpendicular to the central axis of the solenoid. Assuming that the infinite-solenoid approximation is valid at the location of the small coil, determine the magnitude of the emf induced in the coil.

Strategy

The magnetic field in the middle of the solenoid is a uniform value of [latex]{\mu }_{0}nI.[/latex] This field is producing a maximum magnetic flux through the coil as it is directed along the length of the solenoid. Therefore, the magnetic flux through the coil is the product of the solenoid’s magnetic field times the area of the coil. Faraday’s law involves a time derivative of the magnetic flux. The only quantity varying in time is the current, the rest can be pulled out of the time derivative. Lastly, we include the number of turns in the coil to determine the induced emf in the coil.

Solution

Show Answer

Since the field of the solenoid is given by [latex]B={\mu }_{0}nI,[/latex] the flux through each turn of the small coil is

where d is the diameter of the coil. Now from Faraday’s law, the magnitude of the emf induced in the coil is

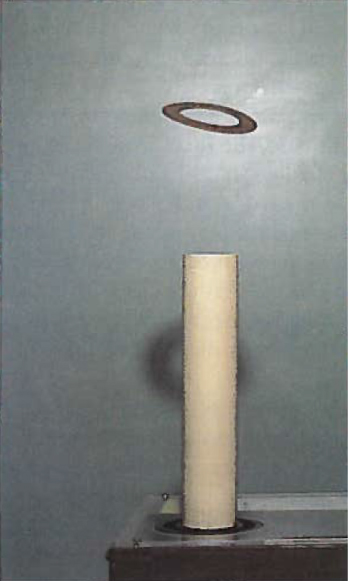

Significance

When the current is turned on in a vertical solenoid, as shown in Figure 13.10, the ring has an induced emf from the solenoid’s changing magnetic flux that opposes the change. The result is that the ring is fired vertically into the air.

Visit this website for a demonstration of the jumping ring from MIT.

Summary

- We can use Lenz’s law to determine the directions of induced magnetic fields, currents, and emfs.

- The direction of an induced emf always opposes the change in magnetic flux that causes the emf, a result known as Lenz’s law.

Conceptual Questions

The circular conducting loops shown in the accompanying figure are parallel, perpendicular to the plane of the page, and coaxial. (a) When the switch S is closed, what is the direction of the current induced in D? (b) When the switch is opened, what is the direction of the current induced in loop D?

Show Solution

a. CW as viewed from the circuit; b. CCW as viewed from the circuit

The north pole of a magnet is moved toward a copper loop, as shown below. If you are looking at the loop from above the magnet, will you say the induced current is circulating clockwise or counterclockwise?

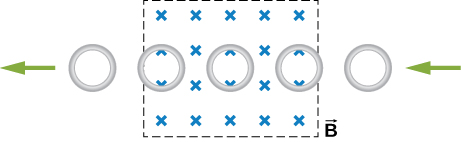

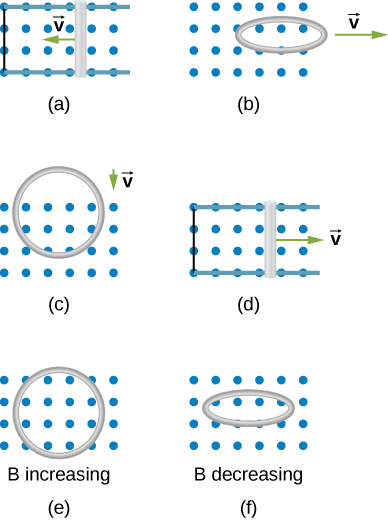

The accompanying figure shows a conducting ring at various positions as it moves through a magnetic field. What is the sense of the induced emf for each of those positions?

Show Solution

As the loop enters, the induced emf creates a CCW current while as the loop leaves the induced emf creates a CW current. While the loop is fully inside the magnetic field, there is no flux change and therefore no induced current.

Show that [latex]\epsilon[/latex] and [latex]d{\text{Φ}}_{\text{m}}\text{/}dt[/latex] have the same units.

State the direction of the induced current for each case shown below, observing from the side of the magnet.

Show Solution

a. CCW viewed from the magnet; b. CW viewed from the magnet; c. CW viewed from the magnet; d. CCW viewed from the magnet; e. CW viewed from the magnet; f. no current

Problems

A single-turn circular loop of wire of radius 50 mm lies in a plane perpendicular to a spatially uniform magnetic field. During a 0.10-s time interval, the magnitude of the field increases uniformly from 200 to 300 mT. (a) Determine the emf induced in the loop. (b) If the magnetic field is directed out of the page, what is the direction of the current induced in the loop?

Show Solution

a. [latex]7.8\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-3}\text{V}[/latex]; b. CCW from the same view as the magnetic field

When a magnetic field is first turned on, the flux through a 20-turn loop varies with time according to [latex]{\text{Φ}}_{\text{m}}=5.0{t}^{2}-2.0t,[/latex] where [latex]{\text{Φ}}_{\text{m}}[/latex] is in milliwebers, t is in seconds, and the loop is in the plane of the page with the unit normal pointing outward. (a) What is the emf induced in the loop as a function of time? What is the direction of the induced current at (b) t = 0, (c) 0.10, (d) 1.0, and (e) 2.0 s?

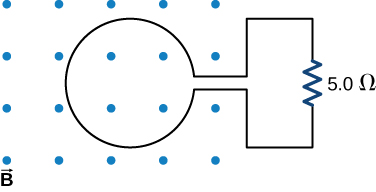

The magnetic flux through the loop shown in the accompanying figure varies with time according to [latex]{\text{Φ}}_{\text{m}}=2.00{e}^{-3t}\text{sin}\left(120\pi t\right),[/latex] where [latex]{\text{Φ}}_{\text{m}}[/latex] is in milliwebers. What are the direction and magnitude of the current through the [latex]5.00\text{-}\text{Ω}[/latex] resistor at (a) [latex]t=0[/latex]; (b) [latex]t=2.17\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}1{0}^{\text{−}2}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{s},[/latex] and (c) [latex]t=3.00\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{s?}[/latex]

Show Solution

a. 150 A downward through the resistor; b. 46 A upward through the resistor; c. 0.019 A downward through the resistor

Use Lenz’s law to determine the direction of induced current in each case.

Glossary

- Lenz’s law

- direction of an induced emf opposes the change in magnetic flux that produced it; this is the negative sign in Faraday’s law

Licenses and Attributions

Lenz's Law. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-2/pages/13-2-lenzs-law. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-2/pages/1-introduction