Chapter 2. The Kinetic Theory of Gases

2.3 Heat Capacity and Equipartition of Energy

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Solve problems involving heat transfer to and from ideal monatomic gases whose volumes are held constant

- Solve similar problems for non-monatomic ideal gases based on the number of degrees of freedom of a molecule

- Estimate the heat capacities of metals using a model based on degrees of freedom

In the chapter on temperature and heat, we defined the specific heat capacity with the equation [latex]Q=mc\text{Δ}T,[/latex] or [latex]c=\left(1\text{/}m\right)Q\text{/}\text{Δ}T[/latex]. However, the properties of an ideal gas depend directly on the number of moles in a sample, so here we define specific heat capacity in terms of the number of moles, not the mass. Furthermore, when talking about solids and liquids, we ignored any changes in volume and pressure with changes in temperature—a good approximation for solids and liquids, but for gases, we have to make some condition on volume or pressure changes. Here, we focus on the heat capacity with the volume held constant. We can calculate it for an ideal gas.

Heat Capacity of an Ideal Monatomic Gas at Constant Volume

We define the molar heat capacity at constant volume [latex]{C}_{V}[/latex] as

This is often expressed in the form

If the volume does not change, there is no overall displacement, so no work is done, and the only change in internal energy is due to the heat flow [latex]\text{Δ}{E}_{\text{int}}=Q.[/latex] (This statement is discussed further in the next chapter.) We use the equation [latex]{E}_{\text{int}}=3nRT\text{/}2[/latex] to write [latex]\text{Δ}{E}_{\text{int}}=3nR\text{Δ}T\text{/}2[/latex] and substitute [latex]\text{Δ}E[/latex] for Q to find [latex]Q=3nR\text{Δ}T\text{/}2[/latex], which gives the following simple result for an ideal monatomic gas:

It is independent of temperature, which justifies our use of finite differences instead of a derivative. This formula agrees well with experimental results.

In the next chapter we discuss the molar specific heat at constant pressure [latex]{C}_{p},[/latex] which is always greater than [latex]{C}_{V}.[/latex]

Example

Calculating Temperature

A sample of 0.125 kg of xenon is contained in a rigid metal cylinder, big enough that the xenon can be modeled as an ideal gas, at a temperature of [latex]20.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex]. The cylinder is moved outside on a hot summer day. As the xenon comes into equilibrium by reaching the temperature of its surroundings, 180 J of heat are conducted to it through the cylinder walls. What is the equilibrium temperature? Ignore the expansion of the metal cylinder.

Solution

Show Answer

- Identify the knowns: We know the initial temperature [latex]{T}_{1}[/latex] is [latex]20.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex], the heat Q is 180 J, and the mass m of the xenon is 0.125 kg.

- Identify the unknown. We need the final temperature, so we’ll need [latex]\text{Δ}T[/latex].

- Determine which equations are needed. Because xenon gas is monatomic, we can use [latex]Q=3nR\text{Δ}T\text{/}2.[/latex] Then we need the number of moles, [latex]n=m\text{/}M.[/latex]

- Substitute the known values into the equations and solve for the unknowns.

The molar mass of xenon is 131.3 g, so we obtain

Therefore, the final temperature is [latex]35.2\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex]. The problem could equally well be solved in kelvin; as a kelvin is the same size as a degree Celsius of temperature change, you would get [latex]\text{Δ}T=15.2\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{K}\text{.}[/latex]

Significance

The heating of an ideal or almost ideal gas at constant volume is important in car engines and many other practical systems.

Check Your Understanding

Suppose 2 moles of helium gas at 200 K are mixed with 2 moles of krypton gas at 400 K in a calorimeter. What is the final temperature?

Show Solution

As the number of moles is equal and we know the molar heat capacities of the two gases are equal, the temperature is halfway between the initial temperatures, 300 K.

We would like to generalize our results to ideal gases with more than one atom per molecule. In such systems, the molecules can have other forms of energy beside translational kinetic energy, such as rotational kinetic energy and vibrational kinetic and potential energies. We will see that a simple rule lets us determine the average energies present in these forms and solve problems in much the same way as we have for monatomic gases.

Degrees of Freedom

In the previous section, we found that [latex]\frac{1}{2}m\stackrel{\text{–}}{{v}^{2}}=\frac{3}{2}{k}_{\text{B}}T[/latex] and [latex]\stackrel{\text{–}}{{v}^{2}}=3\stackrel{\text{–}}{{v}_{x}^{2}}[/latex], from which it follows that [latex]\frac{1}{2}m\stackrel{\text{–}}{{v}_{x}^{2}}=\frac{1}{2}{k}_{\text{B}}T[/latex]. The same equation holds for [latex]\stackrel{\text{–}}{{v}_{y}^{2}}[/latex] and for [latex]\stackrel{\text{–}}{{v}_{z}^{2}}[/latex]. Thus, we can look at our energy of [latex]\frac{3}{2}{k}_{\text{B}}T[/latex] as the sum of contributions of [latex]\frac{1}{2}{k}_{\text{B}}T[/latex] from each of the three dimensions of translational motion. Shifting to the gas as a whole, we see that the 3 in the formula [latex]{C}_{V}=\frac{3}{2}R[/latex] also reflects those three dimensions. We define a degree of freedom as an independent possible motion of a molecule, such as each of the three dimensions of translation. Then, letting d represent the number of degrees of freedom, the molar heat capacity at constant volume of a monatomic ideal gas is [latex]{C}_{V}=\frac{d}{2}R,[/latex] where [latex]d=3[/latex].

The branch of physics called statistical mechanics tells us, and experiment confirms, that [latex]{C}_{V}[/latex] of any ideal gas is given by this equation, regardless of the number of degrees of freedom. This fact follows from a more general result, the equipartition theorem, which holds in classical (non-quantum) thermodynamics for systems in thermal equilibrium under technical conditions that are beyond our scope. Here, we mention only that in a system, the energy is shared among the degrees of freedom by collisions.

Equipartition Theorem

The energy of a thermodynamic system in equilibrium is partitioned equally among its degrees of freedom. Accordingly, the molar heat capacity of an ideal gas is proportional to its number of degrees of freedom, d:

This result is due to the Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell (1831−1871), whose name will appear several more times in this book.

For example, consider a diatomic ideal gas (a good model for nitrogen, [latex]{\text{N}}_{2},[/latex] and oxygen, [latex]{\text{O}}_{2}[/latex]). Such a gas has more degrees of freedom than a monatomic gas. In addition to the three degrees of freedom for translation, it has two degrees of freedom for rotation perpendicular to its axis. Furthermore, the molecule can vibrate along its axis. This motion is often modeled by imagining a spring connecting the two atoms, and we know from simple harmonic motion that such motion has both kinetic and potential energy. Each of these forms of energy corresponds to a degree of freedom, giving two more.

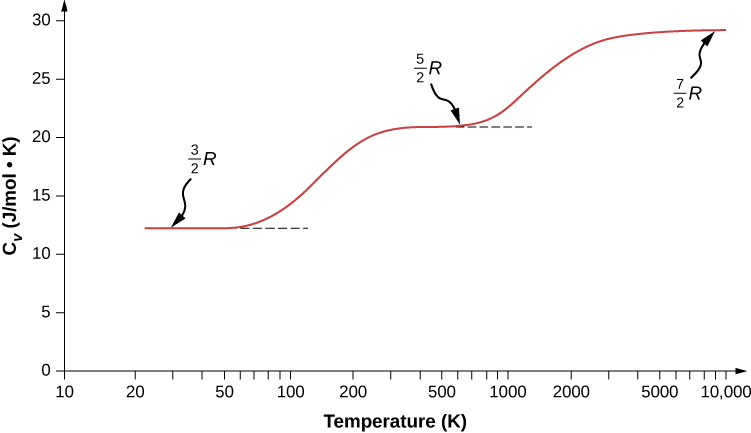

We might expect that for a diatomic gas, we should use 7 as the number of degrees of freedom; classically, if the molecules of a gas had only translational kinetic energy, collisions between molecules would soon make them rotate and vibrate. However, as explained in the previous module, quantum mechanics controls which degrees of freedom are active. The result is shown in Figure 2.13. Both rotational and vibrational energies are limited to discrete values. For temperatures below about 60 K, the energies of hydrogen molecules are too low for a collision to bring the rotational state or vibrational state of a molecule from the lowest energy to the second lowest, so the only form of energy is translational kinetic energy, and [latex]d=3[/latex] or [latex]{C}_{V}=3R\text{/}2[/latex] as in a monatomic gas. Above that temperature, the two rotational degrees of freedom begin to contribute, that is, some molecules are excited to the rotational state with the second-lowest energy. (This temperature is much lower than that where rotations of monatomic gases contribute, because diatomic molecules have much higher rotational inertias and hence much lower rotational energies.) From about room temperature (a bit less than 300 K) to about 600 K, the rotational degrees of freedom are fully active, but the vibrational ones are not, and [latex]d=5[/latex]. Then, finally, above about 3000 K, the vibrational degrees of freedom are fully active, and [latex]d=7[/latex] as the classical theory predicted.

Polyatomic molecules typically have one additional rotational degree of freedom at room temperature, since they have comparable moments of inertia around any axis. Thus, at room temperature, they have [latex]d=6,[/latex] and at high temperature, [latex]d=8.[/latex] We usually assume that gases have the theoretical room-temperature values of d.

As shown in Table 2.3, the results agree well with experiments for many monatomic and diatomic gases, but the agreement for triatomic gases is only fair. The differences arise from interactions that we have ignored between and within molecules.

| Gas | [latex]{C}_{V}\text{/}R[/latex] at [latex]25\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex] and 1 atm |

|---|---|

| Ar | 1.50 |

| He | 1.50 |

| Ne | 1.50 |

| CO | 2.50 |

| [latex]{\text{H}}_{2}[/latex] | 2.47 |

| [latex]{\text{N}}_{2}[/latex] | 2.50 |

| [latex]{\text{O}}_{2}[/latex] | 2.53 |

| [latex]{\text{F}}_{2}[/latex] | 2.8 |

| [latex]{\text{CO}}_{2}[/latex] | 3.48 |

| [latex]{\text{H}}_{2}\text{S}[/latex] | 3.13 |

| [latex]{\text{N}}_{2}\text{O}[/latex] | 3.66 |

What about internal energy for diatomic and polyatomic gases? For such gases, [latex]{C}_{V}[/latex] is a function of temperature (Figure 2.13), so we do not have the kind of simple result we have for monatomic ideal gases.

Molar Heat Capacity of Solid Elements

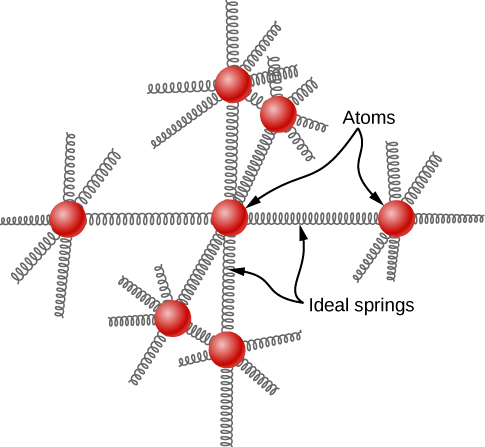

The idea of equipartition leads to an estimate of the molar heat capacity of solid elements at ordinary temperatures. We can model the atoms of a solid as attached to neighboring atoms by springs (Figure 2.14).

Analogously to the discussion of vibration in the previous module, each atom has six degrees of freedom: one kinetic and one potential for each of the x-, y-, and z-directions. Accordingly, the molar specific heat of a metal should be 3R. This result, known as the Law of Dulong and Petit, works fairly well experimentally at room temperature. (For every element, it fails at low temperatures for quantum-mechanical reasons. Since quantum effects are particularly important for low-mass particles, the Law of Dulong and Petit already fails at room temperature for some light elements, such as beryllium and carbon. It also fails for some heavier elements for various reasons beyond what we can cover.)

Problem-Solving Strategy: Heat Capacity and Equipartition

The strategy for solving these problems is the same as the one in Phase Changes for the effects of heat transfer. The only new feature is that you should determine whether the case just presented—ideal gases at constant volume—applies to the problem. (For solid elements, looking up the specific heat capacity is generally better than estimating it from the Law of Dulong and Petit.) In the case of an ideal gas, determine the number d of degrees of freedom from the number of atoms in the gas molecule and use it to calculate [latex]{C}_{V}[/latex] (or use [latex]{C}_{V}[/latex] to solve for d).

Example

Calculating Temperature: Calorimetry with an Ideal Gas

A 300-g piece of solid gallium (a metal used in semiconductor devices) at its melting point of only [latex]30.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°}\text{C}[/latex] is in contact with 12.0 moles of air (assumed diatomic) at [latex]95.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°}\text{C}[/latex] in an insulated container. When the air reaches equilibrium with the gallium, 202 g of the gallium have melted. Based on those data, what is the heat of fusion of gallium? Assume the volume of the air does not change and there are no other heat transfers.

Strategy

We’ll use the equation [latex]{Q}_{\text{hot}}+{Q}_{\text{cold}}=0.[/latex] As some of the gallium doesn’t melt, we know the final temperature is still the melting point. Then the only [latex]{Q}_{\text{hot}}[/latex] is the heat lost as the air cools, [latex]{Q}_{\text{hot}}={n}_{\text{air}}{C}_{V}\text{Δ}T,[/latex] where [latex]{C}_{V}=5R\text{/}2.[/latex] The only [latex]{Q}_{\text{cold}}[/latex] is the latent heat of fusion of the gallium, [latex]{Q}_{\text{cold}}={m}_{\text{Ga}}{L}_{\text{f}}.[/latex] It is positive because heat flows into the gallium.

Solution

Show Answer

- Set up the equation:

- Substitute the known values and solve:

[latex]\left(12.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{mol}\right)\left(\frac{5}{2}\right)\left(8.31\frac{\text{J}}{\text{mol}·\text{°}\text{C}}\right)\left(30.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°}\text{C}-95.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}\right)+\left(0.202\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{kg}\right){\text{L}}_{\text{f}}=0.[/latex]

We solve to find that the heat of fusion of gallium is 80.2 kJ/kg.

Summary

- Every degree of freedom of an ideal gas contributes [latex]\frac{1}{2}{k}_{\text{B}}T[/latex] per atom or molecule to its changes in internal energy.

- Every degree of freedom contributes [latex]\frac{1}{2}R[/latex] to its molar heat capacity at constant volume [latex]{C}_{V}.[/latex]

- Degrees of freedom do not contribute if the temperature is too low to excite the minimum energy of the degree of freedom as given by quantum mechanics. Therefore, at ordinary temperatures, [latex]d=3[/latex] for monatomic gases, [latex]d=5[/latex] for diatomic gases, and [latex]d\approx 6[/latex] for polyatomic gases.

Conceptual Questions

Experimentally it appears that many polyatomic molecules’ vibrational degrees of freedom can contribute to some extent to their energy at room temperature. Would you expect that fact to increase or decrease their heat capacity from the value R? Explain.

One might think that the internal energy of diatomic gases is given by [latex]{E}_{\text{int}}=5RT\text{/}2.[/latex] Do diatomic gases near room temperature have more or less internal energy than that? Hint: Their internal energy includes the total energy added in raising the temperature from the boiling point (very low) to room temperature.

Show Solution

Less, because at lower temperatures their heat capacity was only 3RT/2.

You mix 5 moles of [latex]{\text{H}}_{2}[/latex] at 300 K with 5 moles of He at 360 K in a perfectly insulated calorimeter. Is the final temperature higher or lower than 330 K?

Problems

To give a helium atom nonzero angular momentum requires about 21.2 eV of energy (that is, 21.2 eV is the difference between the energies of the lowest-energy or ground state and the lowest-energy state with angular momentum). The electron-volt or eV is defined as [latex]1.60\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-19}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J}\text{.}[/latex] Find the temperature T where this amount of energy equals [latex]{k}_{\text{B}}T\text{/}2.[/latex] Does this explain why we can ignore the rotational energy of helium for most purposes? (The results for other monatomic gases, and for diatomic gases rotating around the axis connecting the two atoms, have comparable orders of magnitude.)

Show Solution

[latex]4.92\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{5}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{K}[/latex]; Yes, that’s an impractically high temperature.

(a) How much heat must be added to raise the temperature of 1.5 mol of air from [latex]25.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex] to [latex]33.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex] at constant volume? Assume air is completely diatomic. (b) Repeat the problem for the same number of moles of xenon, Xe.

A sealed, rigid container of 0.560 mol of an unknown ideal gas at a temperature of [latex]30.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex] is cooled to [latex]-40.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex]. In the process, 980 J of heat are removed from the gas. Is the gas monatomic, diatomic, or polyatomic?

Show Solution

polyatomic

A sample of neon gas (Ne, molar mass [latex]M=20.2\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{g/mol}[/latex]) at a temperature of [latex]13.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex] is put into a steel container of mass 47.2 g that’s at a temperature of [latex]-40.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex]. The final temperature is[latex]-28.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex]. (No heat is exchanged with the surroundings, and you can neglect any change in the volume of the container.) What is the mass of the sample of neon?

A steel container of mass 135 g contains 24.0 g of ammonia, [latex]{\text{NH}}_{3}[/latex], which has a molar mass of 17.0 g/mol. The container and gas are in equilibrium at [latex]12.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex]. How much heat has to be removed to reach a temperature of [latex]-20.0\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex] ? Ignore the change in volume of the steel.

Show Solution

[latex]3.08\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{3}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J}[/latex]

A sealed room has a volume of [latex]24\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{\text{m}}^{3}[/latex]. It’s filled with air, which may be assumed to be diatomic, at a temperature of [latex]24\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex] and a pressure of [latex]9.83\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{4}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{Pa}\text{.}[/latex] A 1.00-kg block of ice at its melting point is placed in the room. Assume the walls of the room transfer no heat. What is the equilibrium temperature?

Heliox, a mixture of helium and oxygen, is sometimes given to hospital patients who have trouble breathing, because the low mass of helium makes it easier to breathe than air. Suppose helium at [latex]25\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex] is mixed with oxygen at [latex]35\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex] to make a mixture that is [latex]70%[/latex] helium by mole. What is the final temperature? Ignore any heat flow to or from the surroundings, and assume the final volume is the sum of the initial volumes.

Show Solution

[latex]29.2\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex]

Professional divers sometimes use heliox, consisting of [latex]79%[/latex] helium and [latex]21%[/latex] oxygen by mole. Suppose a perfectly rigid scuba tank with a volume of 11 L contains heliox at an absolute pressure of [latex]2.1\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{7}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{Pa}[/latex] at a temperature of [latex]31\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex]. (a) How many moles of helium and how many moles of oxygen are in the tank? (b) The diver goes down to a point where the sea temperature is [latex]27\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex] while using a negligible amount of the mixture. As the gas in the tank reaches this new temperature, how much heat is removed from it?

In car racing, one advantage of mixing liquid nitrous oxide [latex]\left({\text{N}}_{2}\text{O}\right)[/latex] with air is that the boiling of the “nitrous” absorbs latent heat of vaporization and thus cools the air and ultimately the fuel-air mixture, allowing more fuel-air mixture to go into each cylinder. As a very rough look at this process, suppose 1.0 mol of nitrous oxide gas at its boiling point, [latex]-88\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex], is mixed with 4.0 mol of air (assumed diatomic) at [latex]30\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex]. What is the final temperature of the mixture? Use the measured heat capacity of [latex]{\text{N}}_{2}\text{O}[/latex] at [latex]25\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex], which is [latex]30.4\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{J/mol}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex]. (The primary advantage of nitrous oxide is that it consists of 1/3 oxygen, which is more than air contains, so it supplies more oxygen to burn the fuel. Another advantage is that its decomposition into nitrogen and oxygen releases energy in the cylinder.)

Show Solution

[latex]-1.6\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{°C}[/latex]

Glossary

- degree of freedom

- independent kind of motion possessing energy, such as the kinetic energy of motion in one of the three orthogonal spatial directions

- equipartition theorem

- theorem that the energy of a classical thermodynamic system is shared equally among its degrees of freedom

Licenses and Attributions

Heat Capacity and Equipartition of Energy. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-2/pages/2-3-heat-capacity-and-equipartition-of-energy. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-2/pages/1-introduction