Chapter 5. Electric Charges and Fields

5.2 Conductors, Insulators, and Charging by Induction

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain what a conductor is

- Explain what an insulator is

- List the differences and similarities between conductors and insulators

- Describe the process of charging by induction

In the preceding section, we said that scientists were able to create electric charge only on nonmetallic materials and never on metals. To understand why this is the case, you have to understand more about the nature and structure of atoms. In this section, we discuss how and why electric charges do—or do not—move through materials (Figure 5.9). A more complete description is given in a later chapter.

Conductors and Insulators

As discussed in the previous section, electrons surround the tiny nucleus in the form of a (comparatively) vast cloud of negative charge. However, this cloud does have a definite structure to it. Let’s consider an atom of the most commonly used conductor, copper.

For reasons that will become clear in Atomic Structure, there is an outermost electron that is only loosely bound to the atom’s nucleus. It can be easily dislodged; it then moves to a neighboring atom. In a large mass of copper atoms (such as a copper wire or a sheet of copper), these vast numbers of outermost electrons (one per atom) wander from atom to atom, and are the electrons that do the moving when electricity flows. These wandering, or “free,” electrons are called conduction electrons, and copper is therefore an excellent conductor (of electric charge). All conducting elements have a similar arrangement of their electrons, with one or two conduction electrons. This includes most metals.

Insulators, in contrast, are made from materials that lack conduction electrons; charge flows only with great difficulty, if at all. Even if excess charge is added to an insulating material, it cannot move, remaining indefinitely in place. This is why insulating materials exhibit the electrical attraction and repulsion forces described earlier, whereas conductors do not; any excess charge placed on a conductor would instantly flow away (due to mutual repulsion from existing charges), leaving no excess charge around to create forces. Charge cannot flow along or through an insulator, so its electric forces remain for long periods of time. (Charge will dissipate from an insulator, given enough time.) As it happens, amber, fur, and most semi-precious gems are insulators, as are materials like wood, glass, and plastic.

Charging by Induction

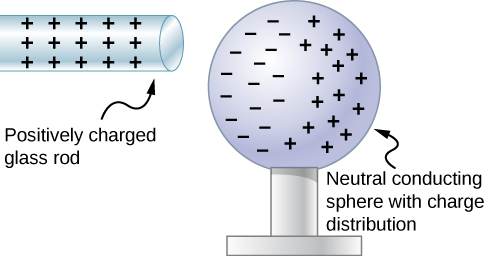

Let’s examine in more detail what happens in a conductor when an electrically charged object is brought close to it. As mentioned, the conduction electrons in the conductor are able to move with nearly complete freedom. As a result, when a charged insulator (such as a positively charged glass rod) is brought close to the conductor, the (total) charge on the insulator exerts an electric force on the conduction electrons. Since the rod is positively charged, the conduction electrons (which themselves are negatively charged) are attracted, flowing toward the insulator to the near side of the conductor (Figure 5.10).

Now, the conductor is still overall electrically neutral; the conduction electrons have changed position, but they are still in the conducting material. However, the conductor now has a charge distribution; the near end (the portion of the conductor closest to the insulator) now has more negative charge than positive charge, and the reverse is true of the end farthest from the insulator. The relocation of negative charges to the near side of the conductor results in an overall positive charge in the part of the conductor farthest from the insulator. We have thus created an electric charge distribution where one did not exist before. This process is referred to as inducing polarization—in this case, polarizing the conductor. The resulting separation of positive and negative charge is called polarization, and a material, or even a molecule, that exhibits polarization is said to be polarized. A similar situation occurs with a negatively charged insulator, but the resulting polarization is in the opposite direction.

The result is the formation of what is called an electric dipole, from a Latin phrase meaning “two ends.” The presence of electric charges on the insulator—and the electric forces they apply to the conduction electrons—creates, or “induces,” the dipole in the conductor.

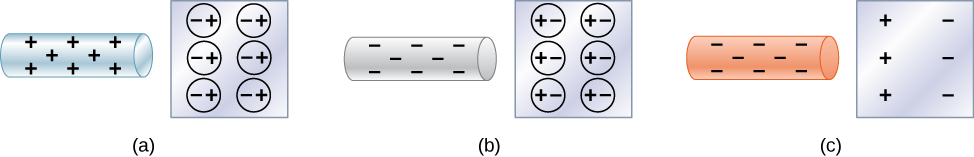

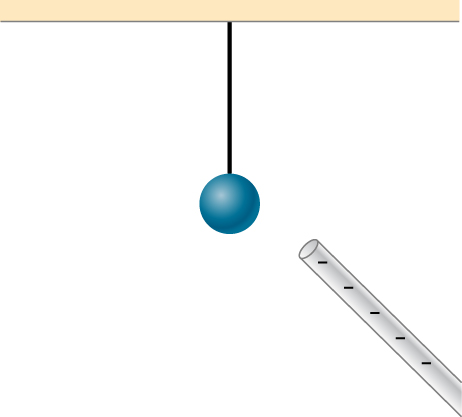

Neutral objects can be attracted to any charged object. The pieces of straw attracted to polished amber are neutral, for example. If you run a plastic comb through your hair, the charged comb can pick up neutral pieces of paper. Figure 5.11 shows how the polarization of atoms and molecules in neutral objects results in their attraction to a charged object.

When a charged rod is brought near a neutral substance, an insulator in this case, the distribution of charge in atoms and molecules is shifted slightly. Opposite charge is attracted nearer the external charged rod, while like charge is repelled. Since the electrostatic force decreases with distance, the repulsion of like charges is weaker than the attraction of unlike charges, and so there is a net attraction. Thus, a positively charged glass rod attracts neutral pieces of paper, as will a negatively charged rubber rod. Some molecules, like water, are polar molecules. Polar molecules have a natural or inherent separation of charge, although they are neutral overall. Polar molecules are particularly affected by other charged objects and show greater polarization effects than molecules with naturally uniform charge distributions.

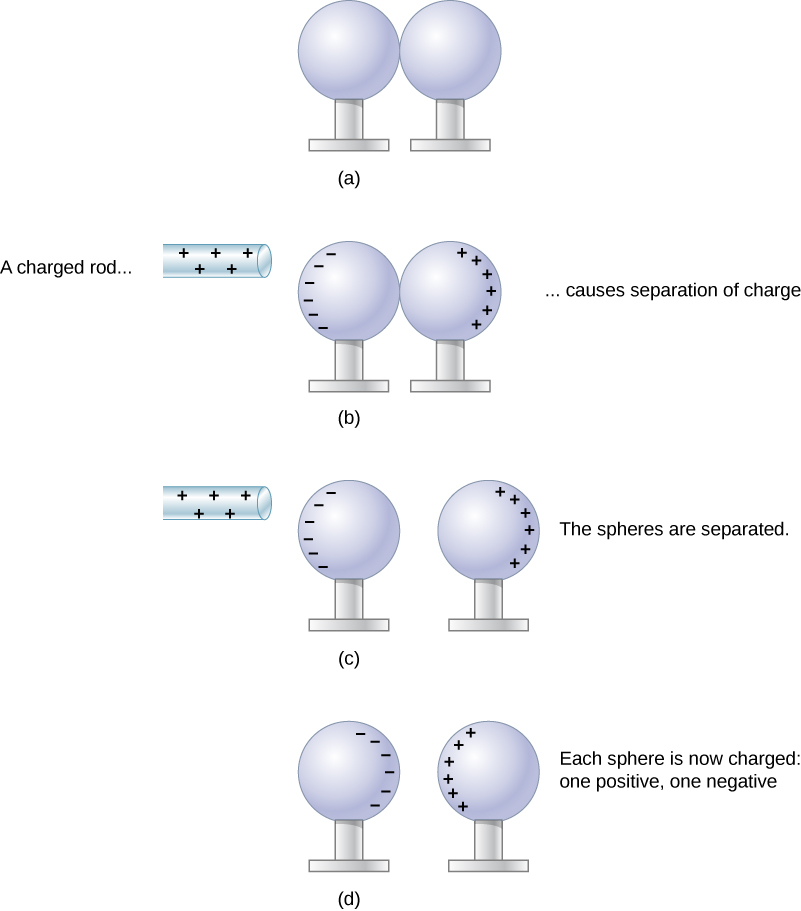

When the two ends of a dipole can be separated, this method of charging by induction may be used to create charged objects without transferring charge. In Figure 5.12, we see two neutral metal spheres in contact with one another but insulated from the rest of the world. A positively charged rod is brought near one of them, attracting negative charge to that side, leaving the other sphere positively charged.

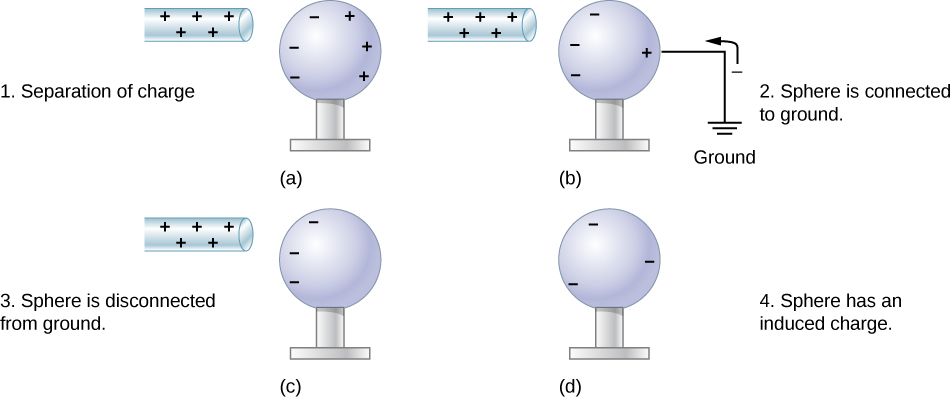

Another method of charging by induction is shown in Figure 5.13. The neutral metal sphere is polarized when a charged rod is brought near it. The sphere is then grounded, meaning that a conducting wire is run from the sphere to the ground. Since Earth is large and most of the ground is a good conductor, it can supply or accept excess charge easily. In this case, electrons are attracted to the sphere through a wire called the ground wire, because it supplies a conducting path to the ground. The ground connection is broken before the charged rod is removed, leaving the sphere with an excess charge opposite to that of the rod. Again, an opposite charge is achieved when charging by induction, and the charged rod loses none of its excess charge.

Summary

- A conductor is a substance that allows charge to flow freely through its atomic structure.

- An insulator holds charge fixed in place.

- Polarization is the separation of positive and negative charges in a neutral object. Polarized objects have their positive and negative charges concentrated in different areas, giving them a charge distribution.

Conceptual Questions

An eccentric inventor attempts to levitate a cork ball by wrapping it with foil and placing a large negative charge on the ball and then putting a large positive charge on the ceiling of his workshop. Instead, while attempting to place a large negative charge on the ball, the foil flies off. Explain.

When a glass rod is rubbed with silk, it becomes positive and the silk becomes negative—yet both attract dust. Does the dust have a third type of charge that is attracted to both positive and negative? Explain.

Show Solution

No, the dust is attracted to both because the dust particle molecules become polarized in the direction of the silk.

Why does a car always attract dust right after it is polished? (Note that car wax and car tires are insulators.)

Does the uncharged conductor shown below experience a net electric force?

Show Solution

Yes, polarization charge is induced on the conductor so that the positive charge is nearest the charged rod, causing an attractive force.

While walking on a rug, a person frequently becomes charged because of the rubbing between his shoes and the rug. This charge then causes a spark and a slight shock when the person gets close to a metal object. Why are these shocks so much more common on a dry day?

Compare charging by conduction to charging by induction.

Show Solution

Charging by conduction is charging by contact where charge is transferred to the object. Charging by induction first involves producing a polarization charge in the object and then connecting a wire to ground to allow some of the charge to leave the object, leaving the object charged.

Small pieces of tissue are attracted to a charged comb. Soon after sticking to the comb, the pieces of tissue are repelled from it. Explain.

Trucks that carry gasoline often have chains dangling from their undercarriages and brushing the ground. Why?

Show Solution

This is so that any excess charge is transferred to the ground, keeping the gasoline receptacles neutral. If there is excess charge on the gasoline receptacle, a spark could ignite it.

Why do electrostatic experiments work so poorly in humid weather?

Why do some clothes cling together after being removed from the clothes dryer? Does this happen if they’re still damp?

Show Solution

The dryer charges the clothes. If they are damp, the presence of water molecules suppresses the charge.

Can induction be used to produce charge on an insulator?

Suppose someone tells you that rubbing quartz with cotton cloth produces a third kind of charge on the quartz. Describe what you might do to test this claim.

Show Solution

There are only two types of charge, attractive and repulsive. If you bring a charged object near the quartz, only one of these two effects will happen, proving there is not a third kind of charge.

A handheld copper rod does not acquire a charge when you rub it with a cloth. Explain why.

Suppose you place a charge q near a large metal plate. (a) If q is attracted to the plate, is the plate necessarily charged? (b) If q is repelled by the plate, is the plate necessarily charged?

Show Solution

a. No, since a polarization charge is induced. b. Yes, since the polarization charge would produce only an attractive force.

Problems

Suppose a speck of dust in an electrostatic precipitator has [latex]1.0000\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{12}[/latex] protons in it and has a net charge of −5.00 nC (a very large charge for a small speck). How many electrons does it have?

Show Solution

[latex]5.00\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-9}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{C}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\left(6.242\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{18}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{e}\text{/}\text{C}\right)=3.121\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{10}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{e}[/latex];

[latex]3.121\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{10}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{e}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{+}1.0000\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{12}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{e}=1.0312\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{12}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{e}[/latex]

An amoeba has [latex]1.00\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{16}[/latex] protons and a net charge of 0.300 pC. (a) How many fewer electrons are there than protons? (b) If you paired them up, what fraction of the protons would have no electrons?

A 50.0-g ball of copper has a net charge of [latex]2.00\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\mu \text{C}[/latex]. What fraction of the copper’s electrons has been removed? (Each copper atom has 29 protons, and copper has an atomic mass of 63.5.)

Show Solution

atomic mass of copper atom times [latex]1\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{u}=1.055\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-25}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{kg}[/latex];

number of copper atoms [latex]=4.739\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{23}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{atoms}[/latex];

number of electrons equals 29 times number of atoms or [latex]1.374\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{25}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{electrons}[/latex]; [latex]\frac{2.00\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-6}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{C}\left(6.242\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{18}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{e}\text{/}\text{C}\right)}{1.374\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{25}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{e}}=9.083\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-13}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{or}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}9.083\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-11}\text{%}[/latex]

What net charge would you place on a 100-g piece of sulfur if you put an extra electron on 1 in [latex]{10}^{12}[/latex] of its atoms? (Sulfur has an atomic mass of 32.1 u.)

How many coulombs of positive charge are there in 4.00 kg of plutonium, given its atomic mass is 244 and that each plutonium atom has 94 protons?

Show Solution

[latex]244.00\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{u}\left(1.66\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-27}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{kg}\text{/}\text{u}\right)=4.050\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-25}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{kg}[/latex];

[latex]\frac{4.00\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{kg}}{4.050\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-25}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{kg}}=9.877\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{24}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{atoms}\phantom{\rule{1em}{0ex}}9.877\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{24}\left(94\right)=9.284\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{26}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{protons}[/latex];

[latex]9.284\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{26}\left(1.602\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{-19}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{C}\text{/}\text{p}\right)=1.487\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}×\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}{10}^{8}\phantom{\rule{0.2em}{0ex}}\text{C}[/latex]

Glossary

- charging by induction

- process by which an electrically charged object brought near a neutral object creates a charge separation in that object

- conduction electron

- electron that is free to move away from its atomic orbit

- conductor

- material that allows electrons to move separately from their atomic orbits; object with properties that allow charges to move about freely within it

- dipole

- two equal and opposite charges that are fixed close to each other

- insulator

- material that holds electrons securely within their atomic orbits

- polarization

- slight shifting of positive and negative charges to opposite sides of an object

Licenses and Attributions

Conductors, Insulators, and Charging by Induction. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-2/pages/5-2-conductors-insulators-and-charging-by-induction. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/university-physics-volume-2/pages/1-introduction