Biopsychology

Lobes of the Brain

Learning Objectives

- Identify the location and function of the lobes of the brain

Forebrain Structures

Lobes of the Brain

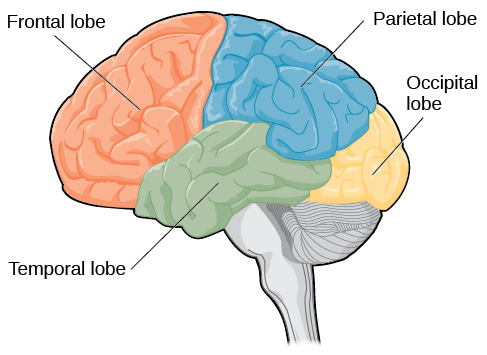

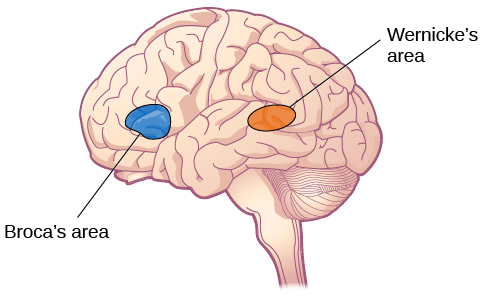

The four lobes of the brain are the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes (Figure 2). The frontal lobe is located in the forward part of the brain, extending back to a fissure known as the central sulcus. The frontal lobe is involved in reasoning, motor control, emotion, and language. It contains the motor cortex, which is involved in planning and coordinating movement; the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for higher-level cognitive functioning; and Broca’s area, which is essential for language production.

People who suffer damage to Broca’s area have great difficulty producing language of any form. For example, Padma was an electrical engineer who was socially active and a caring, involved mother. About twenty years ago, she was in a car accident and suffered damage to her Broca’s area. She completely lost the ability to speak and form any kind of meaningful language. There is nothing wrong with her mouth or her vocal cords, but she is unable to produce words. She can follow directions but can’t respond verbally, and she can read but no longer write. She can do routine tasks like running to the market to buy milk, but she could not communicate verbally if a situation called for it.

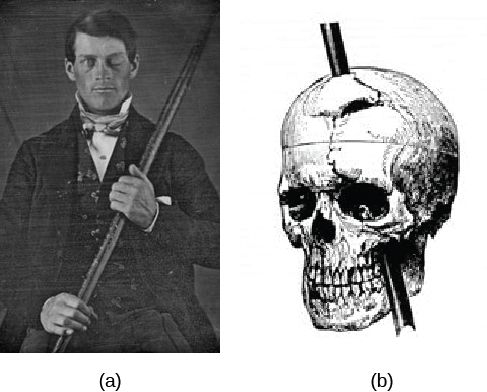

Probably the most famous case of frontal lobe damage is that of a man by the name of Phineas Gage. On September 13, 1848, Gage (age 25) was working as a railroad foreman in Vermont. He and his crew were using an iron rod to tamp explosives down into a blasting hole to remove rock along the railway’s path. Unfortunately, the iron rod created a spark and caused the rod to explode out of the blasting hole, into Gage’s face, and through his skull (Figure 3). Although lying in a pool of his own blood with brain matter emerging from his head, Gage was conscious and able to get up, walk, and speak. But in the months following his accident, people noticed that his personality had changed. Many of his friends described him as no longer being himself. Before the accident, it was said that Gage was a well-mannered, soft-spoken man, but he began to behave in odd and inappropriate ways after the accident. Such changes in personality would be consistent with loss of impulse control—a frontal lobe function.

Beyond the damage to the frontal lobe itself, subsequent investigations into the rod’s path also identified probable damage to pathways between the frontal lobe and other brain structures, including the limbic system. With connections between the planning functions of the frontal lobe and the emotional processes of the limbic system severed, Gage had difficulty controlling his emotional impulses.

However, there is some evidence suggesting that the dramatic changes in Gage’s personality were exaggerated and embellished. Gage’s case occurred in the midst of a 19th century debate over localization—regarding whether certain areas of the brain are associated with particular functions. On the basis of extremely limited information about Gage, the extent of his injury, and his life before and after the accident, scientists tended to find support for their own views, on whichever side of the debate they fell (Macmillan, 1999).

Link to learning

Watch this clip about Phineas Gage to learn more about his accident and injury.

You can view the transcript for “Phineas Gage (LEGO Stop-Motion Video)” (opens in new window).

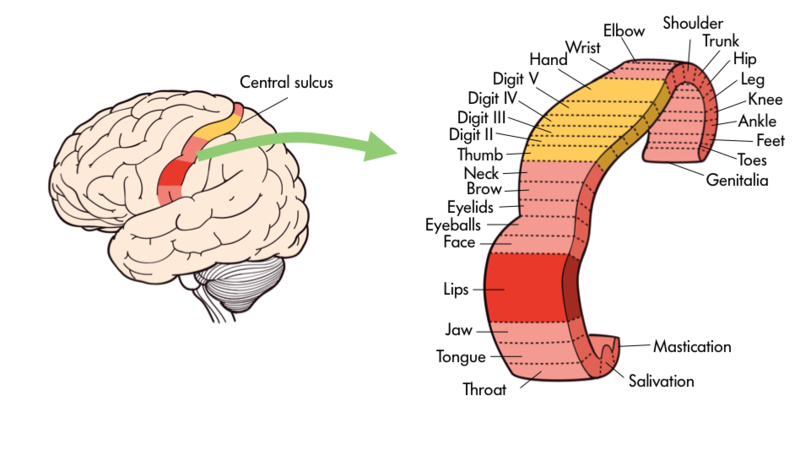

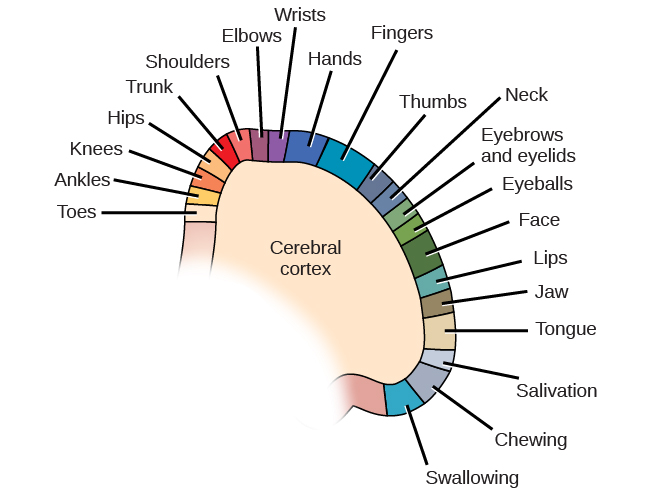

One particularly fascinating area in the frontal lobe is called the “primary motor cortex”. This strip running along the side of the brain is in charge of voluntary movements like waving goodbye, wiggling your eyebrows, and kissing. It is an excellent example of the way that the various regions of the brain are highly specialized. Interestingly, each of our various body parts has a unique portion of the primary motor cortex devoted to it. Each individual finger has about as much dedicated brain space as your entire leg. Your lips, in turn, require about as much dedicated brain processing as all of your fingers and your hand combined!

Because the cerebral cortex in general, and the frontal lobe in particular, are associated with such sophisticated functions as planning and being self-aware they are often thought of as a higher, less primal portion of the brain. Indeed, other animals such as rats and kangaroos while they do have frontal regions of their brain do not have the same level of development in the cerebral cortices. The closer an animal is to humans on the evolutionary tree—think chimpanzees and gorillas, the more developed is this portion of their brain.

The brain’s parietal lobe is located immediately behind the frontal lobe, and is involved in processing information from the body’s senses. It contains the somatosensory cortex, which is essential for processing sensory information from across the body, such as touch, temperature, and pain. The somatosensory cortex is organized topographically, which means that spatial relationships that exist in the body are maintained on the surface of the somatosensory cortex. For example, the portion of the cortex that processes sensory information from the hand is adjacent to the portion that processes information from the wrist.

The temporal lobe is located on the side of the head (temporal means “near the temples”), and is associated with hearing, memory, emotion, and some aspects of language. The auditory cortex, the main area responsible for processing auditory information, is located within the temporal lobe. Wernicke’s area, important for speech comprehension, is also located here. Whereas individuals with damage to Broca’s area have difficulty producing language, those with damage to Wernicke’s area can produce sensible language, but they are unable to understand it.

The occipital lobe is located at the very back of the brain, and contains the primary visual cortex, which is responsible for interpreting incoming visual information. The occipital cortex is organized retinotopically, which means there is a close relationship between the position of an object in a person’s visual field and the position of that object’s representation on the cortex. You will learn much more about how visual information is processed in the occipital lobe when you study sensation and perception.

Food for Thought

Consider the following advice from Joseph LeDoux, a professor of neuroscience and psychology at New York University, as you learn about the specific parts of the brain:

Be suspicious of any statement that says a brain area is a center responsible for some function. The notion of functions being products of brain areas or centers is left over from the days when most evidence about brain function was based on the effects of brain lesions localized to specific areas. Today, we think of functions as products of systems rather than of areas. Neurons in areas contribute because they are part of a system. The amygdala, for example, contributes to threat detection because it is part of a threat detection system. And just because the amygdala contributes to threat detection does not mean that threat detection is the only function to which it contributes. Amygdala neurons, for example, are also components of systems that process the significance of stimuli related to eating, drinking, sex, and addictive drugs.

Licenses and Attributions (Click to expand)

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- The Brain and Spinal Cord. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/3-4-the-brain-and-spinal-cord. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction.

- The Amygdala Is Not The Brains Fear Center. Authored by: Joseph LeDoux. Located at: http://thepsychreport.com/science/the-amygdala-is-not-the-brains-fear-center/. Project: The Psych Report. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Motor cortex paragraphs and image. Authored by: Robert Biswas-Diener. Provided by: Portland State University. Located at: http://nobaproject.com/modules/the-brain-and-nervous-system. Project: The Noba Project. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

All rights reserved content

- Phineas Gage (LEGO Stop-Motion Music Video). Authored by: Brad Wray. Located at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_nikOxNfjqs. License: Other. License Terms: Standard YouTube License

surface of the brain that is associated with our highest mental capabilities

largest part of the brain, containing the cerebral cortex, the thalamus, and the limbic system, among other structures

part of the cerebral cortex involved in reasoning, motor control, emotion, and language; contains motor cortex

depressions or grooves in the cerebral cortex

strip of cortex involved in planning and coordinating movement

area in the frontal lobe responsible for higher-level cognitive functioning

region in the left hemisphere that is essential for language production

part of the cerebral cortex involved in processing various sensory and perceptual information; contains the primary somatosensory cortex

essential for processing sensory information from across the body, such as touch, temperature, and pain

part of cerebral cortex associated with hearing, memory, emotion, and some aspects of language; contains primary auditory cortex

strip of cortex in the temporal lobe that is responsible for processing auditory information

important for speech comprehension

part of the cerebral cortex associated with visual processing; contains the primary visual cortex