Chapter 3: Creating New Social Orders: Colonial Societies, 1500–1700

Introduction

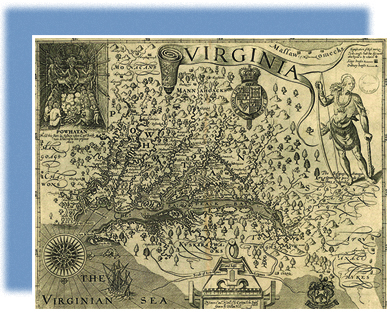

By the mid-seventeenth century, the geopolitical map of North America had become a patchwork of imperial designs and ambitions as the Spanish, Dutch, French, and English reinforced their claims to parts of the land. Uneasiness, punctuated by violent clashes, prevailed in the border zones between the Europeans’ territorial claims. Meanwhile, still-powerful native peoples waged war to drive the invaders from the continent. In the Chesapeake Bay and New England colonies, conflicts erupted as the English pushed against their native neighbors (Figure 3.1).

The rise of colonial societies in the Americas brought Native Americans, Africans, and Europeans together for the first time, highlighting the radical social, cultural, and religious differences that hampered their ability to understand each other. European settlement affected every aspect of the land and its people, bringing goods, ideas, and diseases that transformed the Americas. Reciprocally, Native American practices, such as the use of tobacco, profoundly altered European habits and tastes.