Condensed Matter Physics

Superconductivity

Samuel J. Ling; Jeff Sanny; and William Moebs

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the main features of a superconductor

- Describe the BCS theory of superconductivity

- Determine the critical magnetic field for T = 0 K from magnetic field data

- Calculate the maximum emf or current for a wire to remain superconducting

Electrical resistance can be considered as a measure of the frictional force in electrical current flow. Thus, electrical resistance is a primary source of energy dissipation in electrical systems such as electromagnets, electric motors, and transmission lines. Copper wire is commonly used in electrical wiring because it has one of the lowest room-temperature electrical resistivities among common conductors. (Actually, silver has a lower resistivity than copper, but the high cost and limited availability of silver outweigh its savings in energy over copper.)

Although our discussion of conductivity seems to imply that all materials must have electrical resistance, we know that this is not the case. When the temperature decreases below a critical value for many materials, their electrical resistivity drops to zero, and the materials become superconductors (see Superconductors).

Watch this NOVA video excerpt, Making Stuff Colder, as an introduction to the topic of superconductivity and its many applications.

Properties of Superconductors

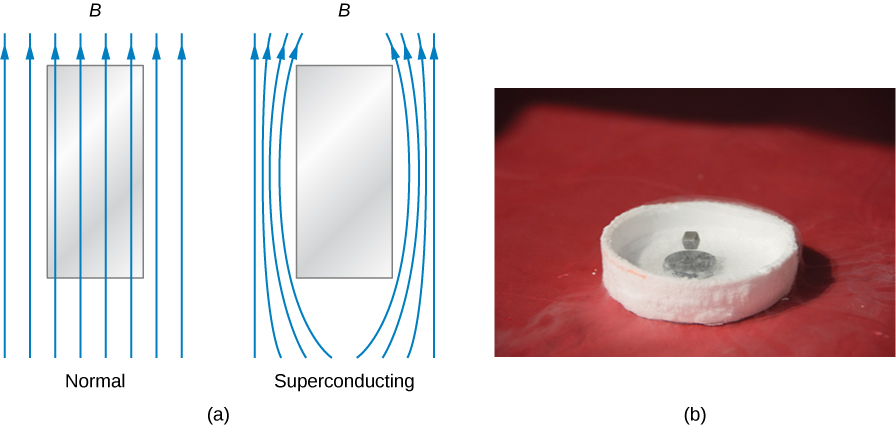

In addition to zero electrical resistance, superconductors also have perfect diamagnetism. In other words, in the presence of an applied magnetic field, the net magnetic field within a superconductor is always zero ((Figure)). Therefore, any magnetic field lines that pass through a superconducting sample when it is in its normal state are expelled once the sample becomes superconducting. These are manifestations of the Meissner effect, which you learned about in the chapter on current and resistance.

Interestingly, the Meissner effect is not a consequence of the resistance being zero. To see why, suppose that a sample placed in a magnetic field undergoes a transition in which its resistance drops to zero. From Ohm’s law, the current density, j, in the sample is related to the net internal electric field, E, and the resistivity ![]() by

by ![]() . If

. If ![]() is zero, E must also be zero so that j can remain finite. Now E and the magnetic flux

is zero, E must also be zero so that j can remain finite. Now E and the magnetic flux ![]() through the sample are related by Faraday’s law as

through the sample are related by Faraday’s law as

If E is zero, ![]() is also zero, that is, the magnetic flux through the sample cannot change. The magnetic field lines within the sample should therefore not be expelled when the transition occurs. Hence, it does not follow that a material whose resistance goes to zero has to exhibit the Meissner effect. Rather, the Meissner effect is a special property of superconductors.

is also zero, that is, the magnetic flux through the sample cannot change. The magnetic field lines within the sample should therefore not be expelled when the transition occurs. Hence, it does not follow that a material whose resistance goes to zero has to exhibit the Meissner effect. Rather, the Meissner effect is a special property of superconductors.

Another important property of a superconducting material is its critical temperature, ![]() , the temperature below which the material is superconducting. The known range of critical temperatures is from a fraction of 1 K to slightly above 100 K. Superconductors with critical temperatures near this higher limit are commonly known as “high-temperature” superconductors. From a practical standpoint, superconductors for which

, the temperature below which the material is superconducting. The known range of critical temperatures is from a fraction of 1 K to slightly above 100 K. Superconductors with critical temperatures near this higher limit are commonly known as “high-temperature” superconductors. From a practical standpoint, superconductors for which ![]() are very important. At present, applications involving superconductors often still require that superconducting materials be immersed in liquid helium (4.2 K) in order to keep them below their critical temperature. The liquid helium baths must be continually replenished because of evaporation, and cooling costs can easily outweigh the savings in using a superconductor. However, 77 K is the temperature of liquid nitrogen, which is far more abundant and inexpensive than liquid helium. It would be much more cost-effective if we could easily fabricate and use high-temperature superconductor components that only need to be kept in liquid nitrogen baths to maintain their superconductivity.

are very important. At present, applications involving superconductors often still require that superconducting materials be immersed in liquid helium (4.2 K) in order to keep them below their critical temperature. The liquid helium baths must be continually replenished because of evaporation, and cooling costs can easily outweigh the savings in using a superconductor. However, 77 K is the temperature of liquid nitrogen, which is far more abundant and inexpensive than liquid helium. It would be much more cost-effective if we could easily fabricate and use high-temperature superconductor components that only need to be kept in liquid nitrogen baths to maintain their superconductivity.

High-temperature superconducting materials are presently in use in various applications. An example is the production of magnetic fields in some particle accelerators. The ultimate goal is to discover materials that are superconducting at room temperature. Without any cooling requirements, the bulk of electronic components and transmission lines could be superconducting, resulting in dramatic and unprecedented increases in efficiency and performance.

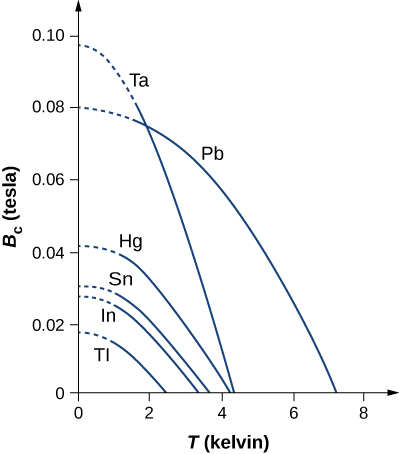

Another important property of a superconducting material is its critical magnetic field ![]() which is the maximum applied magnetic field at a temperature T that will allow a material to remain superconducting. An applied field that is greater than the critical field will destroy the superconductivity. The critical field is zero at the critical temperature and increases as the temperature decreases. Plots of the critical field versus temperature for several superconducting materials are shown in (Figure). The temperature dependence of the critical field can be described approximately by

which is the maximum applied magnetic field at a temperature T that will allow a material to remain superconducting. An applied field that is greater than the critical field will destroy the superconductivity. The critical field is zero at the critical temperature and increases as the temperature decreases. Plots of the critical field versus temperature for several superconducting materials are shown in (Figure). The temperature dependence of the critical field can be described approximately by

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com {B}_{\text{c}}\left(T\right)={B}_{\text{c}}\left(0\right)\left[1-{\left(\frac{T}{{T}_{\text{c}}}\right)}^{2}\right]](https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-ac9778da5bdbc235dbf7f8eb58731171_l3.png)

where ![]() is the critical field at absolute zero temperature. (Figure) lists the critical temperatures and fields for two classes of superconductors: type I superconductor and type II superconductor. In general, type I superconductors are elements, such as aluminum and mercury. They are perfectly diamagnetic below a critical field BC(T), and enter the normal non-superconducting state once that field is exceeded. The critical fields of type I superconductors are generally quite low (well below one tesla). For this reason, they cannot be used in applications requiring the production of high magnetic fields, which would destroy their superconducting state.

is the critical field at absolute zero temperature. (Figure) lists the critical temperatures and fields for two classes of superconductors: type I superconductor and type II superconductor. In general, type I superconductors are elements, such as aluminum and mercury. They are perfectly diamagnetic below a critical field BC(T), and enter the normal non-superconducting state once that field is exceeded. The critical fields of type I superconductors are generally quite low (well below one tesla). For this reason, they cannot be used in applications requiring the production of high magnetic fields, which would destroy their superconducting state.

| Material | Critical Temperature |

Critical Magnetic Field |

|---|---|---|

| Type I | ||

| Type II | ||

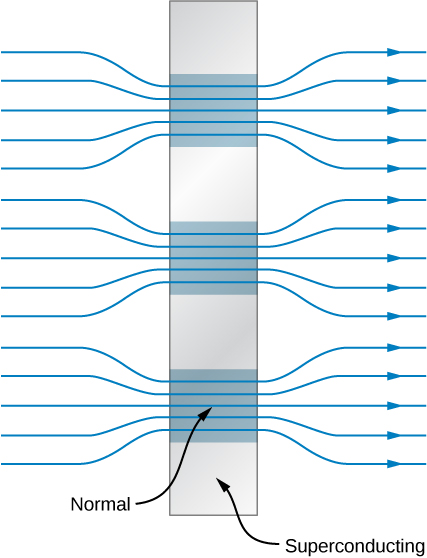

Type II superconductors are generally compounds or alloys involving transition metals or actinide series elements. Almost all superconductors with relatively high critical temperatures are type II. They have two critical fields, represented by ![]() and

and ![]() . When the field is below

. When the field is below ![]() type II superconductors are perfectly diamagnetic, and no magnetic flux penetration into the material can occur. For a field exceeding

type II superconductors are perfectly diamagnetic, and no magnetic flux penetration into the material can occur. For a field exceeding ![]() they are driven into their normal state. When the field is greater than

they are driven into their normal state. When the field is greater than ![]() but less than

but less than ![]() type II superconductors are said to be in a mixed state. Although there is some magnetic flux penetration in the mixed state, the resistance of the material is zero. Within the superconductor, filament-like regions exist that have normal electrical and magnetic properties interspersed between regions that are superconducting with perfect diamagnetism. A representation of this state is given in (Figure). The magnetic field is expelled from the superconducting regions but exists in the normal regions. In general,

type II superconductors are said to be in a mixed state. Although there is some magnetic flux penetration in the mixed state, the resistance of the material is zero. Within the superconductor, filament-like regions exist that have normal electrical and magnetic properties interspersed between regions that are superconducting with perfect diamagnetism. A representation of this state is given in (Figure). The magnetic field is expelled from the superconducting regions but exists in the normal regions. In general, ![]() is very large compared with the critical fields of type I superconductors, so wire made of type II superconducting material is suitable for the windings of high-field magnets.

is very large compared with the critical fields of type I superconductors, so wire made of type II superconducting material is suitable for the windings of high-field magnets.

Niobium Wire In an experiment, a niobium (Nb) wire of radius 0.25 mm is immersed in liquid helium (![]() ) and required to carry a current of 300 A. Does the wire remain superconducting?

) and required to carry a current of 300 A. Does the wire remain superconducting?

Strategy The applied magnetic field can be determined from the radius of the wire and current. The critical magnetic field can be determined from (Figure), the properties of the superconductor, and the temperature. If the applied magnetic field is greater than the critical field, then superconductivity in the Nb wire is destroyed.

Solution At ![]() the critical field for Nb is, from (Figure) and (Figure),

the critical field for Nb is, from (Figure) and (Figure),

In an earlier chapter, we learned the magnetic field inside a current-carrying wire of radius a is given by

where r is the distance from the central axis of the wire. Thus, the field at the surface of the wire is ![]() For the niobium wire, this field is

For the niobium wire, this field is

Since this exceeds the critical 0.16 T, the wire does not remain superconducting.

Significance Superconductivity requires low temperatures and low magnetic fields. These simultaneous conditions are met less easily for Nb than for many other metals. For example, aluminum superconducts at temperatures 7 times lower and magnetic fields 18 times lower.

Check Your Understanding What conditions are necessary for superconductivity?

a low temperature and low magnetic field

Theory of Superconductors

A successful theory of superconductivity was developed in the 1950s by John Bardeen, Leon Cooper, and J. Robert Schrieffer, for which they received the Nobel Prize in 1972. This theory is known as the BCS theory. BCS theory is complex, so we summarize it qualitatively below.

In a normal conductor, the electrical properties of the material are due to the most energetic electrons near the Fermi energy. In 1956, Cooper showed that if there is any attractive interaction between two electrons at the Fermi level, then the electrons can form a bound state in which their total energy is less than ![]() . Two such electrons are known as a Cooper pair.

. Two such electrons are known as a Cooper pair.

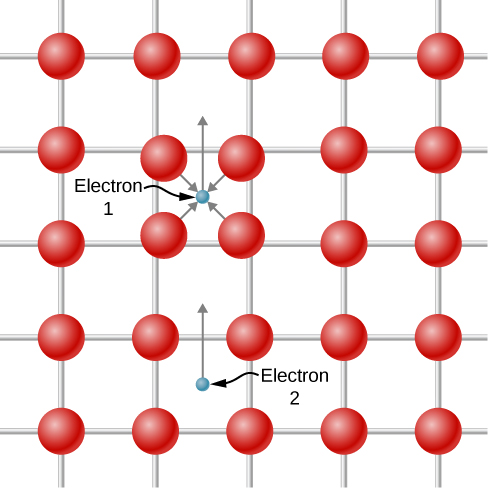

It is hard to imagine two electrons attracting each other, since they have like charge and should repel. However, the proposed interaction occurs only in the context of an atomic lattice. A depiction of the attraction is shown in (Figure). Electron 1 slightly displaces the positively charged atomic nuclei toward itself as it travels past because of the Coulomb attraction. Electron 2 “sees” a region with a higher density of positive charge relative to the surroundings and is therefore attracted into this region and, therefore indirectly, to electron 1. Because of the exclusion principle, the two electrons of a Cooper pair must have opposite spin.

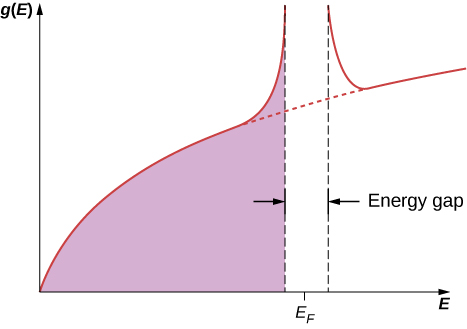

The BCS theory extends Cooper’s ideas, which are for a single pair of electrons, to the entire free electron gas. When the transition to the superconducting state occurs, all the electrons pair up to form Cooper pairs. On an atomic scale, the distance between the two electrons making up a Cooper pair is quite large. Between these electrons are typically about ![]() other electrons, each also pairs with a distant electron. Hence, there is considerable overlap between the wave functions of the individual Cooper pairs, resulting in a strong correlation among the motions of the pairs. They all move together “in step,” like the members of a marching band. In the superconducting transition, the density of states becomes drastically changed near the Fermi level. As shown in (Figure), an energy gap appears around

other electrons, each also pairs with a distant electron. Hence, there is considerable overlap between the wave functions of the individual Cooper pairs, resulting in a strong correlation among the motions of the pairs. They all move together “in step,” like the members of a marching band. In the superconducting transition, the density of states becomes drastically changed near the Fermi level. As shown in (Figure), an energy gap appears around ![]() because the collection of Cooper pairs has lower ground state energy than the Fermi gas of noninteracting electrons. The appearance of this gap characterizes the superconducting state. If this state is destroyed, then the gap disappears, and the density of states reverts to that of the free electron gas.

because the collection of Cooper pairs has lower ground state energy than the Fermi gas of noninteracting electrons. The appearance of this gap characterizes the superconducting state. If this state is destroyed, then the gap disappears, and the density of states reverts to that of the free electron gas.

The BCS theory is able to predict many of the properties observed in superconductors. Examples include the Meissner effect, the critical temperature, the critical field, and, perhaps most importantly, the resistivity becoming zero at a critical temperature. We can think about this last phenomenon qualitatively as follows. In a normal conductor, resistivity results from the interaction of the conduction electrons with the lattice. In this interaction, the energy exchanged is on the order of ![]() the thermal energy. In a superconductor, electric current is carried by the Cooper pairs. The only way for a lattice to scatter a Cooper pair is to break it up. The destruction of one pair then destroys the collective motion of all the pairs. This destruction requires energy on the order of

the thermal energy. In a superconductor, electric current is carried by the Cooper pairs. The only way for a lattice to scatter a Cooper pair is to break it up. The destruction of one pair then destroys the collective motion of all the pairs. This destruction requires energy on the order of ![]() , which is the size of the energy gap. Below the critical temperature, there is not enough thermal energy available for this process, so the Cooper pairs travel unimpeded throughout the superconductor.

, which is the size of the energy gap. Below the critical temperature, there is not enough thermal energy available for this process, so the Cooper pairs travel unimpeded throughout the superconductor.

Finally, it is interesting to note that no evidence of superconductivity has been found in the best normal conductors, such as copper and silver. This is not unexpected, given the BCS theory. The basis for the formation of the superconducting state is an interaction between the electrons and the lattice. In the best conductors, the electron-lattice interaction is weakest, as evident from their minimal resistivity. We might expect then that in these materials, the interaction is so weak that Cooper pairs cannot be formed, and superconductivity is therefore precluded.

Summary

- A superconductor is characterized by two features: the conduction of electrons with zero electrical resistance and the repelling of magnetic field lines.

- A minimum temperature is required for superconductivity to occur.

- A strong magnetic field destroys superconductivity.

- Superconductivity can be explain in terms of Cooper pairs.

Key Equations

| Electrostatic energy for equilibrium separation distance between atoms | |

| Energy change associated with ionic bonding | |

| Critical magnetic field of a superconductor | ![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com {B}_{\text{c}}\left(T\right)={B}_{\text{c}}\left(0\right)\left[1-{\left(\frac{T}{{T}_{\text{c}}}\right)}^{2}\right]](https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/app/uploads/quicklatex/quicklatex.com-ac9778da5bdbc235dbf7f8eb58731171_l3.png) |

| Rotational energy of a diatomic molecule | |

| Characteristic rotational energy of a molecule | |

| Potential energy associated with the exclusion principle | |

| Dissociation energy of a solid | |

| Moment of inertia of a diatomic molecule with reduced mass |

|

| Electron energy in a metal | |

| Electron density of states of a metal | |

| Fermi energy | |

| Fermi temperature | |

| Hall effect | |

| Current versus bias voltage across p-n junction | |

| Current gain | |

| Selection rule for rotational energy transitions | |

| Selection rule for vibrational energy transitions |

Conceptual Questions

Describe two main features of a superconductor.

How does BCS theory explain superconductivity?

BSC theory explains superconductivity in terms of the interactions between electron pairs (Cooper pairs). One electron in a pair interacts with the lattice, which interacts with the second electron. The combine electron-lattice-electron interaction binds the electron pair together in a way that overcomes their mutual repulsion.

What is the Meissner effect?

What impact does an increasing magnetic field have on the critical temperature of a semiconductor?

As the magnitude of the magnetic field is increased, the critical temperature decreases.

Problems

At what temperature, in terms of ![]() , is the critical field of a superconductor one-half its value at

, is the critical field of a superconductor one-half its value at ![]() ?

?

![]()

What is the critical magnetic field for lead at ![]() ?

?

A Pb wire wound in a tight solenoid of diameter of 4.0 mm is cooled to a temperature of 5.0 K. The wire is connected in series with a ![]() resistor and a variable source of emf. As the emf is increased, what value does it have when the superconductivity of the wire is destroyed?

resistor and a variable source of emf. As the emf is increased, what value does it have when the superconductivity of the wire is destroyed?

61 kV

A tightly wound solenoid at 4.0 K is 50 cm long and is constructed from Nb wire of radius 1.5 mm. What maximum current can the solenoid carry if the wire is to remain superconducting?

Additional Problems

Potassium fluoride (KF) is a molecule formed by an ionic bond. At equilibrium separation the atoms are ![]() apart. Determine the electrostatic potential energy of the atoms. The electron affinity of F is 3.40 eV and the ionization energy of K is 4.34 eV. Determine dissociation energy. (Neglect the energy of repulsion.)

apart. Determine the electrostatic potential energy of the atoms. The electron affinity of F is 3.40 eV and the ionization energy of K is 4.34 eV. Determine dissociation energy. (Neglect the energy of repulsion.)

![]()

For the preceding problem, sketch the potential energy versus separation graph for the bonding of ![]() ions. (a) Label the graph with the energy required to transfer an electron from K to Fl. (b) Label the graph with the dissociation energy.

ions. (a) Label the graph with the energy required to transfer an electron from K to Fl. (b) Label the graph with the dissociation energy.

The separation between hydrogen atoms in a ![]() molecule is about 0.075 nm. Determine the characteristic energy of rotation in eV.

molecule is about 0.075 nm. Determine the characteristic energy of rotation in eV.

![]()

The characteristic energy of the ![]() molecule is

molecule is ![]() . Determine the separation distance between the nitrogen atoms.

. Determine the separation distance between the nitrogen atoms.

Determine the lowest three rotational energy levels of ![]()

![]() ;

; ![]() (no rotation);

(no rotation);![]() ;

; ![]()

A carbon atom can hybridize in the ![]() configuration. (a) What is the angle between the hybrid orbitals?

configuration. (a) What is the angle between the hybrid orbitals?

List five main characteristics of ionic crystals that result from their high dissociation energy.

- They are fairly hard and stable.

- They vaporize at relatively high temperatures (1000 to 2000 K).

- They are transparent to visible radiation, because photons in the visible portion of the spectrum are not energetic enough to excite an electron from its ground state to an excited state.

- They are poor electrical conductors because they contain effectively no free electrons.

- They are usually soluble in water, because the water molecule has a large dipole moment whose electric field is strong enough to break the electrostatic bonds between the ions.

Why is bonding in ![]() favorable? Express your answer in terms of the symmetry of the electron wave function.

favorable? Express your answer in terms of the symmetry of the electron wave function.

Astronomers claim to find evidence of ![]() from light spectra of a distant star. Do you believe them?

from light spectra of a distant star. Do you believe them?

No, He atoms do not contain valence electrons that can be shared in the formation of a chemical bond.

Show that the moment of inertia of a diatomic molecule is ![]() , where

, where ![]() is the reduced mass, and

is the reduced mass, and ![]() is the distance between the masses.

is the distance between the masses.

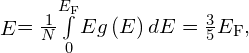

Show that the average energy of an electron in a one-dimensional metal is related to the Fermi energy by ![]()

![]() so

so ![]()

Measurements of a superconductor’s critical magnetic field (in T) at various temperatures (in K) are given below. Use a line of best fit to determine ![]() Assume

Assume ![]()

| T (in K) | |

|---|---|

| 3.0 | 0.18 |

| 4.0 | 0.16 |

| 5.0 | 0.14 |

| 6.0 | 0.12 |

| 7.0 | 0.09 |

| 8.0 | 0.05 |

| 9.0 | 0.01 |

Estimate the fraction of Si atoms that must be replaced by As atoms in order to form an impurity band.

An impurity band will be formed when the density of the donor atoms is high enough that the orbits of the extra electrons overlap. We saw earlier that the orbital radius is about 50 Angstroms, so the maximum distance between the impurities for a band to form is 100 Angstroms. Thus if we use 1 Angstrom as the interatomic distance between the Si atoms, we find that 1 out of 100 atoms along a linear chain must be a donor atom. And in a three-dimensional crystal, roughly 1 out of ![]() atoms must be replaced by a donor atom in order for an impurity band to form.

atoms must be replaced by a donor atom in order for an impurity band to form.

Transition in the rotation spectrum are observed at ordinary room temperature (![]() ). According to your lab partner, a peak in the spectrum corresponds to a transition from the

). According to your lab partner, a peak in the spectrum corresponds to a transition from the ![]() to the

to the ![]() state. Is this possible? If so, determine the momentum of inertia of the molecule.

state. Is this possible? If so, determine the momentum of inertia of the molecule.

Determine the Fermi energies for (a) Mg, (b) Na, and (c) Zn.

a. ![]() ; b.

; b. ![]() ; c.

; c. ![]()

Find the average energy of an electron in a Zn wire.

What value of the repulsion constant, n, gives the measured dissociation energy of 158 kcal/mol for CsCl?

![]()

A physical model of a diamond suggests a BCC packing structure. Why is this not possible?

Challenge Problems

For an electron in a three-dimensional metal, show that the average energy is given by

Where N is the total number electrons in the metal.

In three dimensions, the energy of an electron is given by:

![]() where

where ![]() . Each allowed energy state corresponds to node in N space

. Each allowed energy state corresponds to node in N space ![]() . The number of particles corresponds to the number of states (nodes) in the first octant, within a sphere of radius, R. This number is given by:

. The number of particles corresponds to the number of states (nodes) in the first octant, within a sphere of radius, R. This number is given by: ![]() where the factor 2 accounts for two states of spin. The density of states is found by differentiating this expression by energy:

where the factor 2 accounts for two states of spin. The density of states is found by differentiating this expression by energy:

![]() . Integrating gives:

. Integrating gives: ![]()

Glossary

- BCS theory

- theory of superconductivity based on electron-lattice-electron interactions

- Cooper pair

- coupled electron pair in a superconductor

- critical magnetic field

- maximum field required to produce superconductivity

- critical temperature

- maximum temperature to produce superconductivity

- type I superconductor

- superconducting element, such as aluminum or mercury

- type II superconductor

- superconducting compound or alloy, such as a transition metal or an actinide series element