Condensed Matter Physics

Introduction

Samuel J. Ling; Jeff Sanny; and William Moebs

In this chapter, we examine applications of quantum mechanics to more complex systems, such as molecules, metals, semiconductors, and superconductors. We review and develop concepts of the previous chapters, including wave functions, orbitals, and quantum states. We also introduce many new concepts, including covalent bonding, rotational energy levels, Fermi energy, energy bands, doping, and Cooper pairs.

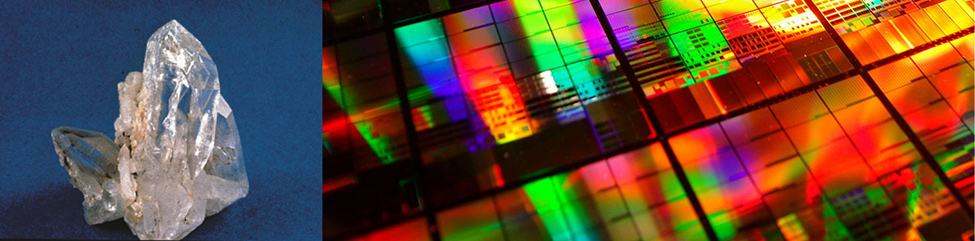

The main topic in this chapter is the crystal structure of solids. For centuries, crystalline solids have been prized for their beauty, including gems like diamonds and emeralds, as well as geological crystals of quartz and metallic ores. But the crystalline structures of semiconductors such as silicon have also made possible the electronics industry of today. In this chapter, we study how the structures of solids give them properties from strength and transparency to electrical conductivity.