Photons and Matter Waves

Introduction

Samuel J. Ling; Jeff Sanny; and William Moebs

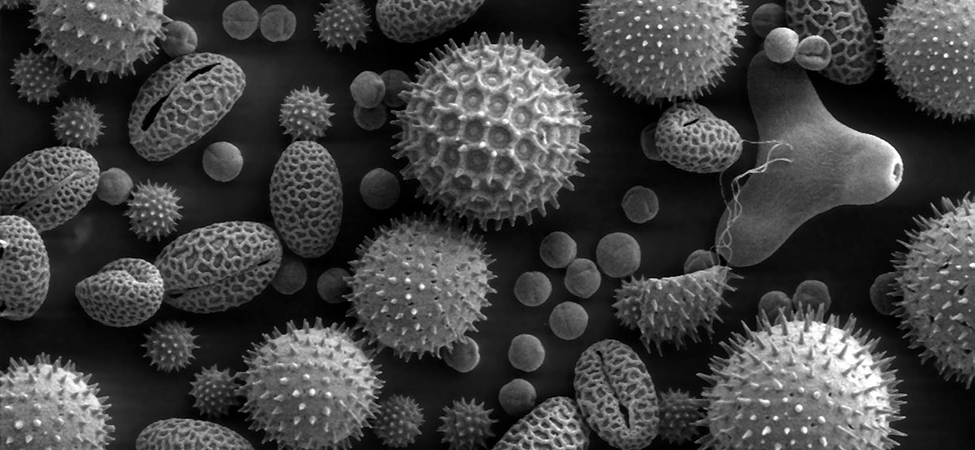

Two of the most revolutionary concepts of the twentieth century were the description of light as a collection of particles, and the treatment of particles as waves. These wave properties of matter have led to the discovery of technologies such as electron microscopy, which allows us to examine submicroscopic objects such as grains of pollen, as shown above.

In this chapter, you will learn about the energy quantum, a concept that was introduced in 1900 by the German physicist Max Planck to explain blackbody radiation. We discuss how Albert Einstein extended Planck’s concept to a quantum of light (a “photon”) to explain the photoelectric effect. We also show how American physicist Arthur H. Compton used the photon concept in 1923 to explain wavelength shifts observed in X-rays. After a discussion of Bohr’s model of hydrogen, we describe how matter waves were postulated in 1924 by Louis-Victor de Broglie to justify Bohr’s model and we examine the experiments conducted in 1923–1927 by Clinton Davisson and Lester Germer that confirmed the existence of de Broglie’s matter waves.