Chapter 31 Radioactivity and Nuclear Physics

31.2 Radiation Detection and Detectors

Summary

- Explain the working principle of a Geiger tube.

- Define and discuss radiation detectors.

It is well known that ionizing radiation affects us but does not trigger nerve impulses. Newspapers carry stories about unsuspecting victims of radiation poisoning who fall ill with radiation sickness, such as burns and blood count changes, but who never felt the radiation directly. This makes the detection of radiation by instruments more than an important research tool. This section is a brief overview of radiation detection and some of its applications.

Human Application

The first direct detection of radiation was Becquerel’s fogged photographic plate. Photographic film is still the most common detector of ionizing radiation, being used routinely in medical and dental x rays. Nuclear radiation is also captured on film, such as seen in Figure 1. The mechanism for film exposure by ionizing radiation is similar to that by photons. A quantum of energy interacts with the emulsion and alters it chemically, thus exposing the film. The quantum come from an [latex]{\alpha}[/latex] -particle, [latex]{\beta}[/latex] -particle, or photon, provided it has more than the few eV of energy needed to induce the chemical change (as does all ionizing radiation). The process is not 100% efficient, since not all incident radiation interacts and not all interactions produce the chemical change. The amount of film darkening is related to exposure, but the darkening also depends on the type of radiation, so that absorbers and other devices must be used to obtain energy, charge, and particle-identification information.

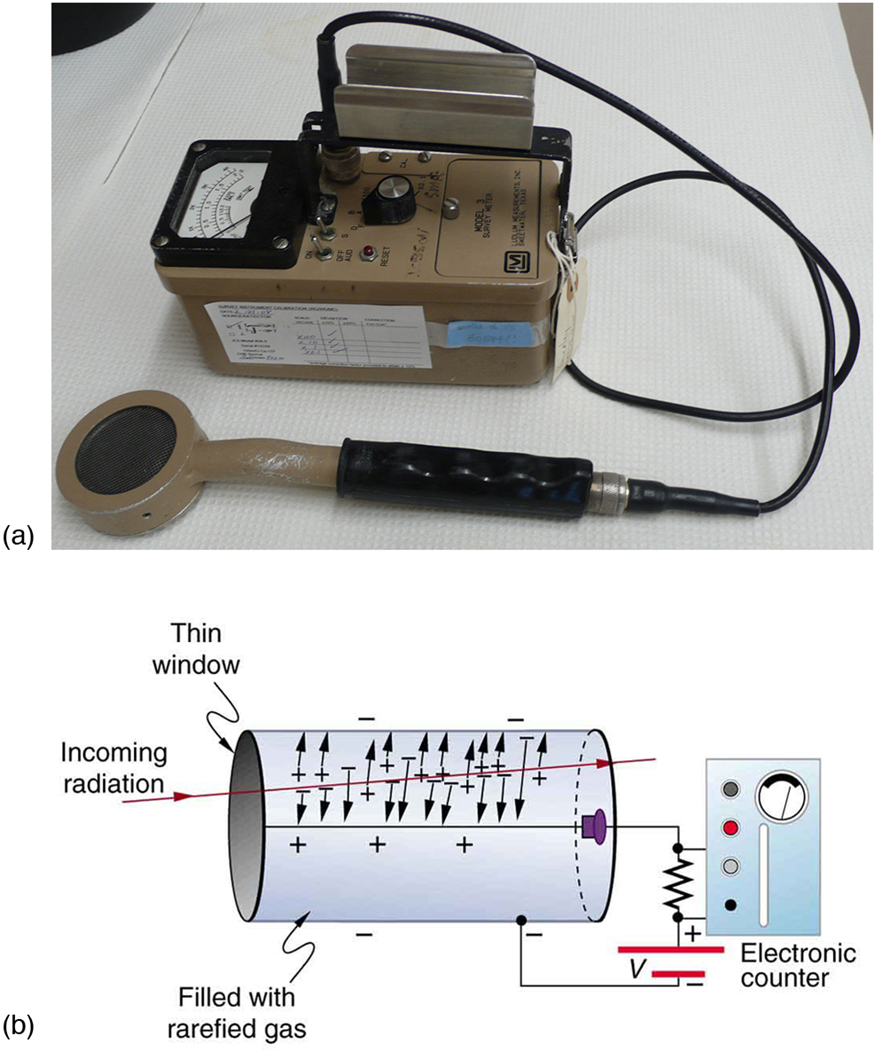

Another very common radiation detector is the Geiger tube. The clicking and buzzing sound we hear in dramatizations and documentaries, as well as in our own physics labs, is usually an audio output of events detected by a Geiger counter. These relatively inexpensive radiation detectors are based on the simple and sturdy Geiger tube, shown schematically in Figure 2(b). A conducting cylinder with a wire along its axis is filled with an insulating gas so that a voltage applied between the cylinder and wire produces almost no current. Ionizing radiation passing through the tube produces free ion pairs that are attracted to the wire and cylinder, forming a current that is detected as a count. The word count implies that there is no information on energy, charge, or type of radiation with a simple Geiger counter. They do not detect every particle, since some radiation can pass through without producing enough ionization to be detected. However, Geiger counters are very useful in producing a prompt output that reveals the existence and relative intensity of ionizing radiation.

Another radiation detection method records light produced when radiation interacts with materials. The energy of the radiation is sufficient to excite atoms in a material that may fluoresce, such as the phosphor used by Rutherford’s group. Materials called scintillators use a more complex collaborative process to convert radiation energy into light. Scintillators may be liquid or solid, and they can be very efficient. Their light output can provide information about the energy, charge, and type of radiation. Scintillator light flashes are very brief in duration, enabling the detection of a huge number of particles in short periods of time. Scintillator detectors are used in a variety of research and diagnostic applications. Among these are the detection by satellite-mounted equipment of the radiation from distant galaxies, the analysis of radiation from a person indicating body burdens, and the detection of exotic particles in accelerator laboratories.

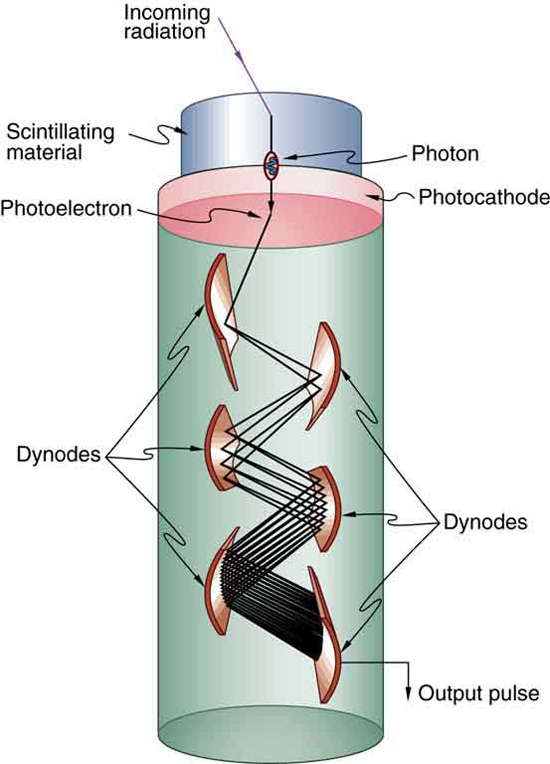

Light from a scintillator is converted into electrical signals by devices such as the photomultiplier tube shown schematically in Figure 3. These tubes are based on the photoelectric effect, which is multiplied in stages into a cascade of electrons, hence the name photomultiplier. Light entering the photomultiplier strikes a metal plate, ejecting an electron that is attracted by a positive potential difference to the next plate, giving it enough energy to eject two or more electrons, and so on. The final output current can be made proportional to the energy of the light entering the tube, which is in turn proportional to the energy deposited in the scintillator. Very sophisticated information can be obtained with scintillators, including energy, charge, particle identification, direction of motion, and so on.

Solid-state radiation detectors convert ionization produced in a semiconductor (like those found in computer chips) directly into an electrical signal. Semiconductors can be constructed that do not conduct current in one particular direction. When a voltage is applied in that direction, current flows only when ionization is produced by radiation, similar to what happens in a Geiger tube. Further, the amount of current in a solid-state detector is closely related to the energy deposited and, since the detector is solid, it can have a high efficiency (since ionizing radiation is stopped in a shorter distance in solids fewer particles escape detection). As with scintillators, very sophisticated information can be obtained from solid-state detectors.

PhET Explorations: Radioactive Dating Game

Learn about different types of radiometric dating, such as carbon dating. Understand how decay and half life work to enable radiometric dating to work. Play a game that tests your ability to match the percentage of the dating element that remains to the age of the object.

Section Summary

- Radiation detectors are based directly or indirectly upon the ionization created by radiation, as are the effects of radiation on living and inert materials.

Conceptual Questions

1: Is it possible for light emitted by a scintillator to be too low in frequency to be used in a photomultiplier tube? Explain.

Problems & Exercises

1: The energy of 30.0 eVeV is required to ionize a molecule of the gas inside a Geiger tube, thereby producing an ion pair. Suppose a particle of ionizing radiation deposits 0.500 MeV of energy in this Geiger tube. What maximum number of ion pairs can it create?

2: A particle of ionizing radiation creates 4000 ion pairs in the gas inside a Geiger tube as it passes through. What minimum energy was deposited, if 30.0 eVis required to create each ion pair?

3: (a) Repeat Chapter 31.2 Exercise 2, and convert the energy to joules or calories. (b) If all of this energy is converted to thermal energy in the gas, what is its temperature increase, assuming [latex]{50.0 \;\text{cm}^3}[/latex] of ideal gas at 0.250-atm pressure? (The small answer is consistent with the fact that the energy is large on a quantum mechanical scale but small on a macroscopic scale.)

4: Suppose a particle of ionizing radiation deposits 1.0 MeV in the gas of a Geiger tube, all of which goes to creating ion pairs. Each ion pair requires 30.0 eV of energy. (a) The applied voltage sweeps the ions out of the gas in [latex]{1.00 \;\mu \text{s}}[/latex]. What is the current? (b) This current is smaller than the actual current since the applied voltage in the Geiger tube accelerates the separated ions, which then create other ion pairs in subsequent collisions. What is the current if this last effect multiplies the number of ion pairs by 900?

Glossary

- Geiger tube

- a very common radiation detector that usually gives an audio output

- photomultiplier

- a device that converts light into electrical signals

- radiation detector

- a device that is used to detect and track the radiation from a radioactive reaction

- scintillators

- a radiation detection method that records light produced when radiation interacts with materials

- solid-state radiation detectors

- semiconductors fabricated to directly convert incident radiation into electrical current

Solutions

Problems & Exercises

1: [latex]{1.67 \times 10^4}[/latex]