Chapter 33 Particle Physics

33.4 Particles, Patterns, and Conservation Laws

Summary

- Define matter and antimatter.

- Outline the differences between hadrons and leptons.

- State the differences between mesons and baryons.

In the early 1930s only a small number of subatomic particles were known to exist—the proton, neutron, electron, photon and, indirectly, the neutrino. Nature seemed relatively simple in some ways, but mysterious in others. Why, for example, should the particle that carries positive charge be almost 2000 times as massive as the one carrying negative charge? Why does a neutral particle like the neutron have a magnetic moment? Does this imply an internal structure with a distribution of moving charges? Why is it that the electron seems to have no size other than its wavelength, while the proton and neutron are about 1 fermi in size? So, while the number of known particles was small and they explained a great deal of atomic and nuclear phenomena, there were many unexplained phenomena and hints of further substructures.

Things soon became more complicated, both in theory and in the prediction and discovery of new particles. In 1928, the British physicist P.A.M. Dirac (see Figure 1) developed a highly successful relativistic quantum theory that laid the foundations of quantum electrodynamics (QED). His theory, for example, explained electron spin and magnetic moment in a natural way. But Dirac’s theory also predicted negative energy states for free electrons. By 1931, Dirac, along with Oppenheimer, realized this was a prediction of positively charged electrons (or positrons). In 1932, American physicist Carl Anderson discovered the positron in cosmic ray studies. The positron, or [latex]{e ^+}[/latex], is the same particle as emitted in [latex]{\beta ^+}[/latex] decay and was the first antimatter that was discovered. In 1935, Yukawa predicted pions as the carriers of the strong nuclear force, and they were eventually discovered. Muons were discovered in cosmic ray experiments in 1937, and they seemed to be heavy, unstable versions of electrons and positrons. After World War II, accelerators energetic enough to create these particles were built. Not only were predicted and known particles created, but many unexpected particles were observed. Initially called elementary particles, their numbers proliferated to dozens and then hundreds, and the term “particle zoo” became the physicist’s lament at the lack of simplicity. But patterns were observed in the particle zoo that led to simplifying ideas such as quarks, as we shall soon see.

Matter and Antimatter

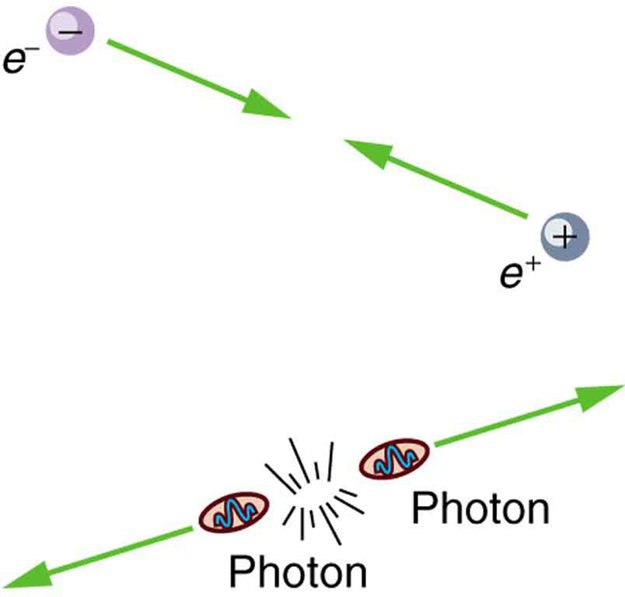

The positron was only the first example of antimatter. Every particle in nature has an antimatter counterpart, although some particles, like the photon, are their own antiparticles. Antimatter has charge opposite to that of matter (for example, the positron is positive while the electron is negative) but is nearly identical otherwise, having the same mass, intrinsic spin, half-life, and so on. When a particle and its antimatter counterpart interact, they annihilate one another, usually totally converting their masses to pure energy in the form of photons as seen in Figure 2. Neutral particles, such as neutrons, have neutral antimatter counterparts, which also annihilate when they interact. Certain neutral particles are their own antiparticle and live correspondingly short lives. For example, the neutral pion [latex]{\pi ^0}[/latex] is its own antiparticle and has a half-life about [latex]{10^{-8}}[/latex] shorter than [latex]{\pi ^+}[/latex] and [latex]{\pi ^-}[/latex], which are each other’s antiparticles. Without exception, nature is symmetric—all particles have antimatter counterparts. For example, antiprotons and antineutrons were first created in accelerator experiments in 1956 and the antiproton is negative. Antihydrogen atoms, consisting of an antiproton and antielectron, were observed in 1995 at CERN, too. It is possible to contain large-scale antimatter particles such as antiprotons by using electromagnetic traps that confine the particles within a magnetic field so that they don't annihilate with other particles. However, particles of the same charge repel each other, so the more particles that are contained in a trap, the more energy is needed to power the magnetic field that contains them. It is not currently possible to store a significant quantity of antiprotons. At any rate, we now see that negative charge is associated with both low-mass (electrons) and high-mass particles (antiprotons) and the apparent asymmetry is not there. But this knowledge does raise another question—why is there such a predominance of matter and so little antimatter? Possible explanations emerge later in this and the next chapter.

Hadrons and Leptons

Particles can also be revealingly grouped according to what forces they feel between them. All particles (even those that are massless) are affected by gravity, since gravity affects the space and time in which particles exist. All charged particles are affected by the electromagnetic force, as are neutral particles that have an internal distribution of charge (such as the neutron with its magnetic moment). Special names are given to particles that feel the strong and weak nuclear forces. Hadrons are particles that feel the strong nuclear force, whereas leptons are particles that do not. The proton, neutron, and the pions are examples of hadrons. The electron, positron, muons, and neutrinos are examples of leptons, the name meaning low mass. Leptons feel the weak nuclear force. In fact, all particles feel the weak nuclear force. This means that hadrons are distinguished by being able to feel both the strong and weak nuclear forces.

Table 2 lists the characteristics of some of the most important subatomic particles, including the directly observed carrier particles for the electromagnetic and weak nuclear forces, all leptons, and some hadrons. Several hints related to an underlying substructure emerge from an examination of these particle characteristics. Note that the carrier particles are called gauge bosons. First mentioned in Chapter 30.7 Patterns in Spectra Reveal More Quantization, a boson is a particle with zero or an integer value of intrinsic spin (such as [latex]{s = 0, 1, 2, \dots}[/latex]), whereas a fermion is a particle with a half-integer value of intrinsic spin ([latex]{s=1/2,3/2, \dots}[/latex]). Fermions obey the Pauli exclusion principle whereas bosons do not. All the known and conjectured carrier particles are bosons.

| Category | Particle name | Symbol | Antiparticle | Rest mass ([latex]{\text{MeV/c}^2}[/latex]) |

[latex]{B}[/latex] | [latex]{L_e}[/latex] | [latex]{L_{\pi}}[/latex] | [latex]{L_{\tau}}[/latex] | [latex]{S}[/latex] | Lifetime2 (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gauge | Photon | [latex]{\gamma}[/latex] | Self | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Stable |

| Bosons | [latex]{W}[/latex] | [latex]{W^+}[/latex] | [latex]{W^-}[/latex] | [latex]{80.39 \times 10^3}[/latex] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | [latex]{1.6 \times 10^{-25}}[/latex] |

| [latex]{Z}[/latex] | [latex]{Z^0}[/latex] | Self | [latex]{91.19 \times 10^3}[/latex] | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | [latex]{1.32 \times 10^{-25}}[/latex] | |

| Leptons | Electron | [latex]{e^-}[/latex] | [latex]{e^+}[/latex] | 0.511 | 0 | [latex]{\pm 1}[/latex] | 0 | 0 | 0 | Stable |

| Neutrino (e) | [latex]{v_e}[/latex] | [latex]{\overline{v}_e}[/latex] | [latex]{0 (7.0 \;\text{eV})}[/latex] 3 | 0 | [latex]{\pm 1}[/latex] | 0 | 0 | 0 | Stable | |

| Muon | [latex]{\mu ^-}[/latex] | [latex]{\mu ^+}[/latex] | 105.7 | 0 | 0 | [latex]{\pm 1}[/latex] | 0 | 0 | [latex]{2.20 \times 10^{-6}}[/latex] | |

| Neutrino [latex]{( \mu )}[/latex] | [latex]{v_{\mu}}[/latex] | [latex]{\overline{v}_{\mu}}[/latex] | [latex]{0(0.27)}[/latex] | 0 | 0 | [latex]{\pm 1}[/latex] | 0 | 0 | Stable | |

| Tau | [latex]{\tau ^-}[/latex] | [latex]{\tau ^+}[/latex] | 1777 | 0 | 0 | 0 | [latex]{\pm 1}[/latex] | 0 | [latex]{2.91 \times 10^{-13}}[/latex] | |

| Neutrino [latex]{( \tau )}[/latex] | [latex]{v_{\tau}}[/latex] | [latex]{\overline{v}^{\tau}}[/latex] | [latex]{0 (31)}[/latex] | 0 | 0 | 0 | [latex]{\pm 1}[/latex] | 0 | Stable | |

| Hadrons (selected) | ||||||||||

| Mesons | Pion | [latex]{\pi ^+}[/latex] | [latex]{\pi ^-}[/latex] | 139.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | [latex]{2.60 \times 10^{-8}}[/latex] |

| [latex]{\pi ^0}[/latex] | Self | 135.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | [latex]{8.4 \times 10^{-17}}[/latex] | ||

| Kaon | [latex]{K^+}[/latex] | [latex]{K^-}[/latex] | 493.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | [latex]{\pm 1}[/latex] | [latex]{1.24 \times 10^{-8}}[/latex] | |

| [latex]{K^0}[/latex] | [latex]{\overline{K} ^0}[/latex] | 497.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | [latex]{\pm 1}[/latex] | [latex]{0.90 \times 10^{-10}}[/latex] | ||

| Eta | [latex]{\eta ^0}[/latex] | Self | 547.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | [latex]{2.53 \times 10^{-19}}[/latex] | |

| (many other mesons known) | ||||||||||

| Baryons | Proton | [latex]{p}[/latex] | [latex]{\overline{p}}[/latex] | 938.3 | ± 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Stable4 |

| Neutron | [latex]{n}[/latex] | [latex]{\overline{n}}[/latex] | 939.6 | ± 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 882 | |

| Lambda | [latex]{\Lambda ^0}[/latex] | [latex]{\overline{\Lambda} ^0}[/latex] | 1115.7 | ± 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | [latex]{\pm 1}[/latex] | [latex]{2.63 \times 10^{-10}}[/latex] | |

| Sigma | [latex]{\Sigma ^+}[/latex] | [latex]{\overline{\Sigma} ^-}[/latex] | 1189.4 | ± 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | [latex]{\pm 1}[/latex] | [latex]{0.80 \times 10^{-10}}[/latex] | |

| [latex]{\Sigma ^0}[/latex] | [latex]{\overline{\Sigma} ^0}[/latex] | 1192.6 | ± 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | [latex]{\pm 1}[/latex] | [latex]{7.4 \times 10^{-20}}[/latex] | ||

| [latex]{\Sigma ^-}[/latex] | [latex]{\overline{\Sigma} ^+}[/latex] | 1197.4 | ± 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | [latex]{\pm 1}[/latex] | [latex]{1.48 \times 10^{-10}}[/latex] | ||

| Xi | [latex]{\Xi ^0}[/latex] | [latex]{\overline{\Xi} ^0}[/latex] | 1314.9 | ± 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | [latex]{\pm 2}[/latex] | [latex]{2.90 \times 10^{-10}}[/latex] | |

| [latex]{\Xi ^-}[/latex] | [latex]{\Xi ^+}[/latex] | 1321.7 | ± 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | [latex]{\pm 2}[/latex] | [latex]{1.64 \times 10^{-10}}[/latex] | ||

| Omega | [latex]{\Omega ^-}[/latex] | [latex]{\Omega ^+}[/latex] | 1672.5 | ± 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | [latex]{\pm 3}[/latex] | [latex]{0.82 \times 10^{-10}}[/latex] | |

| (many other baryons known) | ||||||||||

| Table 2: Selected Particle Characteristics1 | ||||||||||

All known leptons are listed in the table given above. There are only six leptons (and their antiparticles), and they seem to be fundamental in that they have no apparent underlying structure. Leptons have no discernible size other than their wavelength, so that we know they are pointlike down to about [latex]{10^{-18} \;\text{m}}[/latex]. The leptons fall into three families, implying three conservation laws for three quantum numbers. One of these was known from [latex]{\beta}[/latex] decay, where the existence of the electron’s neutrino implied that a new quantum number, called the electron family number [latex]{L_e}[/latex] is conserved. Thus, in [latex]{\beta}[/latex] decay, an antielectron’s neutrino [latex]{\overline{v}_e}[/latex] must be created with [latex]{L_e = -1}[/latex] when an electron with [latex]{L_e = +1}[/latex] is created, so that the total remains 0 as it was before decay.

Once the muon was discovered in cosmic rays, its decay mode was found to be

which implied another “family” and associated conservation principle. The particle [latex]{v_{\mu}}[/latex] is a muon’s neutrino, and it is created to conserve muon family number [latex]{L_{\mu}}[/latex]. So muons are leptons with a family of their own, and conservation of total [latex]{L_{\mu}}[/latex] also seems to be obeyed in many experiments.

More recently, a third lepton family was discovered when [latex]{\pi}[/latex] particles were created and observed to decay in a manner similar to muons. One principal decay mode is

Conservation of total [latex]{L_{\pi}}[/latex] seems to be another law obeyed in many experiments. In fact, particle experiments have found that lepton family number is not universally conserved, due to neutrino “oscillations,” or transformations of neutrinos from one family type to another.

Mesons and Baryons

Now, note that the hadrons in the table given above are divided into two subgroups, called mesons (originally for medium mass) and baryons (the name originally meaning large mass). The division between mesons and baryons is actually based on their observed decay modes and is not strictly associated with their masses. Mesons are hadrons that can decay to leptons and leave no hadrons, which implies that mesons are not conserved in number. Baryons are hadrons that always decay to another baryon. A new physical quantity called baryon number [latex]{B}[/latex] seems to always be conserved in nature and is listed for the various particles in the table given above. Mesons and leptons have [latex]{B = 0}[/latex] so that they can decay to other particles with [latex]{B=0}[/latex]. But baryons have [latex]{B = +1}[/latex] if they are matter, and [latex]{B=-1}[/latex] if they are antimatter. The conservation of total baryon number is a more general rule than first noted in nuclear physics, where it was observed that the total number of nucleons was always conserved in nuclear reactions and decays. That rule in nuclear physics is just one consequence of the conservation of the total baryon number.

Forces, Reactions, and Reaction Rates

The forces that act between particles regulate how they interact with other particles. For example, pions feel the strong force and do not penetrate as far in matter as do muons, which do not feel the strong force. (This was the way those who discovered the muon knew it could not be the particle that carries the strong force—its penetration or range was too great for it to be feeling the strong force.) Similarly, reactions that create other particles, like cosmic rays interacting with nuclei in the atmosphere, have greater probability if they are caused by the strong force than if they are caused by the weak force. Such knowledge has been useful to physicists while analyzing the particles produced by various accelerators.

The forces experienced by particles also govern how particles interact with themselves if they are unstable and decay. For example, the stronger the force, the faster they decay and the shorter is their lifetime. An example of a nuclear decay via the strong force is

[latex]{{^8 \text{Be}} \rightarrow \alpha + \alpha }[/latex] with a lifetime of about [latex]{10^{-16} \;\text{s}}[/latex]. The neutron is a good example of decay via the weak force. The process [latex]{n \rightarrow p + e^- + \overline{v}_e}[/latex] has a longer lifetime of 882 s. The weak force causes this decay, as it does all [latex]{\beta}[/latex] decay. An important clue that the weak force is responsible for [latex]{\beta}[/latex] decay is the creation of leptons, such as [latex]{e^-}[/latex] and [latex]{\overline{v} _e}[/latex]. None would be created if the strong force was responsible, just as no leptons are created in the decay of [latex]{^8 \text{Be}}[/latex]. The systematics of particle lifetimes is a little simpler than nuclear lifetimes when hundreds of particles are examined (not just the ones in the table given above). Particles that decay via the weak force have lifetimes mostly in the range of [latex]{10^{-16}}[/latex] to [latex]{10^{-12}}[/latex] s, whereas those that decay via the strong force have lifetimes mostly in the range of [latex]{10^{-16}}[/latex] to [latex]{10^{-23}}[/latex] s. Turning this around, if we measure the lifetime of a particle, we can tell if it decays via the weak or strong force.

Yet another quantum number emerges from decay lifetimes and patterns. Note that the particles [latex]{\Lambda , \Sigma , \Xi}[/latex], and [latex]{\Omega}[/latex] decay with lifetimes on the order of [latex]{10^{-10}}[/latex] s (the exception is [latex]{\Sigma ^0}[/latex], whose short lifetime is explained by its particular quark substructure.), implying that their decay is caused by the weak force alone, although they are hadrons and feel the strong force. The decay modes of these particles also show patterns—in particular, certain decays that should be possible within all the known conservation laws do not occur. Whenever something is possible in physics, it will happen. If something does not happen, it is forbidden by a rule. All this seemed strange to those studying these particles when they were first discovered, so they named a new quantum number strangeness, given the symbol [latex]{S}[/latex] in the table given above. The values of strangeness assigned to various particles are based on the decay systematics. It is found that strangeness is conserved by the strong force, which governs the production of most of these particles in accelerator experiments. However, strangeness is not conserved by the weak force. This conclusion is reached from the fact that particles that have long lifetimes decay via the weak force and do not conserve strangeness. All of this also has implications for the carrier particles, since they transmit forces and are thus involved in these decays.

Example 1: Calculating Quantum Numbers in Two Decays

(a) The most common decay mode of the [latex]{\Xi ^-}[/latex] particle is [latex]{\Xi ^- \rightarrow \Lambda ^0 + \pi ^-}[/latex]. Using the quantum numbers in the table given above, show that strangeness changes by 1, baryon number and charge are conserved, and lepton family numbers are unaffected.

(b) Is the decay [latex]{K^+ \rightarrow \pi ^+ + \nu _{\mu}}[/latex] allowed, given the quantum numbers in the table given above?

Strategy

In part (a), the conservation laws can be examined by adding the quantum numbers of the decay products and comparing them with the parent particle. In part (b), the same procedure can reveal if a conservation law is broken or not.

Solution for (a)

Before the decay, the [latex]{\Xi ^-}[/latex] has strangeness [latex]{S=-2}[/latex]. After the decay, the total strangeness is –1 for the [latex]{\Lambda ^0}[/latex], plus 0 for the [latex]{\pi ^-}[/latex]. Thus, total strangeness has gone from –2 to –1 or a change of +1. Baryon number for the [latex]{\Xi ^-}[/latex] is [latex]{B=+1}[/latex] before the decay, and after the decay the [latex]{\Lambda ^0}[/latex] has [latex]{B=+1}[/latex] and the [latex]{\pi ^-}[/latex] has [latex]{B=0}[/latex] so that the total baryon number remains +1. Charge is –1 before the decay, and the total charge after is also [latex]{0 - 1= -1}[/latex]. Lepton numbers for all the particles are zero, and so lepton numbers are conserved.

Discussion for (a)

The [latex]{\Xi ^-}[/latex] decay is caused by the weak interaction, since strangeness changes, and it is consistent with the relatively long [latex]{1.64 \times 10^{-10}}[/latex] lifetime of the [latex]{\Xi ^-}[/latex].

Solution for (b)

The decay [latex]{K^+ \rightarrow \mu ^+ + \nu _{\mu}}[/latex] is allowed if charge, baryon number, mass-energy, and lepton numbers are conserved. Strangeness can change due to the weak interaction. Charge is conserved as [latex]{s \rightarrow d}[/latex]. Baryon number is conserved, since all particles have [latex]{B = 0}[/latex]. Mass-energy is conserved in the sense that the [latex]{K^+}[/latex] has a greater mass than the products, so that the decay can be spontaneous. Lepton family numbers are conserved at 0 for the electron and tau family for all particles. The muon family number is [latex]{L_{\mu} = 0}[/latex] before and [latex]{L_{\mu} = -1 +1 =0}[/latex] after. Strangeness changes from +1 before to 0 + 0 after, for an allowed change of 1. The decay is allowed by all these measures.

Discussion for (b)

This decay is not only allowed by our reckoning, it is, in fact, the primary decay mode of the [latex]{K^+}[/latex] meson and is caused by the weak force, consistent with the long [latex]{1.24 \times 10^{-8} \;\text{-s}}[/latex] lifetime.

There are hundreds of particles, all hadrons, not listed in Table 2, most of which have shorter lifetimes. The systematics of those particle lifetimes, their production probabilities, and decay products are completely consistent with the conservation laws noted for lepton families, baryon number, and strangeness, but they also imply other quantum numbers and conservation laws. There are a finite, and in fact relatively small, number of these conserved quantities, however, implying a finite set of substructures. Additionally, some of these short-lived particles resemble the excited states of other particles, implying an internal structure. All of this jigsaw puzzle can be tied together and explained relatively simply by the existence of fundamental substructures. Leptons seem to be fundamental structures. Hadrons seem to have a substructure called quarks. Chapter 33.5 Quarks: Is That All There Is? explores the basics of the underlying quark building blocks.

Summary

- All particles of matter have an antimatter counterpart that has the opposite charge and certain other quantum numbers as seen in Table 2. These matter-antimatter pairs are otherwise very similar but will annihilate when brought together. Known particles can be divided into three major groups—leptons, hadrons, and carrier particles (gauge bosons).

- Leptons do not feel the strong nuclear force and are further divided into three groups—electron family designated by electron family number [latex]{L_e}[/latex]; muon family designated by muon family number [latex]{L_{\mu}}[/latex]; and tau family designated by tau family number [latex]{L_{\tau}}[/latex]. The family numbers are not universally conserved due to neutrino oscillations.

- Hadrons are particles that feel the strong nuclear force and are divided into baryons, with the baryon family number [latex]{B}[/latex] being conserved, and mesons.

Conceptual Questions

1: Large quantities of antimatter isolated from normal matter should behave exactly like normal matter. An antiatom, for example, composed of positrons, antiprotons, and antineutrons should have the same atomic spectrum as its matter counterpart. Would you be able to tell it is antimatter by its emission of antiphotons? Explain briefly.

2: Massless particles are not only neutral, they are chargeless (unlike the neutron). Why is this so?

3: Massless particles must travel at the speed of light, while others cannot reach this speed. Why are all massless particles stable? If evidence is found that neutrinos spontaneously decay into other particles, would this imply they have mass?

4: When a star erupts in a supernova explosion, huge numbers of electron neutrinos are formed in nuclear reactions. Such neutrinos from the 1987A supernova in the relatively nearby Magellanic Cloud were observed within hours of the initial brightening, indicating they traveled to earth at approximately the speed of light. Explain how this data can be used to set an upper limit on the mass of the neutrino, noting that if the mass is small the neutrinos could travel very close to the speed of light and have a reasonable energy (on the order of MeV).

5: Theorists have had spectacular success in predicting previously unknown particles. Considering past theoretical triumphs, why should we bother to perform experiments?

6: What lifetime do you expect for an antineutron isolated from normal matter?

7: Why does the [latex]{\eta ^0}[/latex] meson have such a short lifetime compared to most other mesons?

8: (a) Is a hadron always a baryon?

(b) Is a baryon always a hadron?

(c) Can an unstable baryon decay into a meson, leaving no other baryon?

9: Explain how conservation of baryon number is responsible for conservation of total atomic mass (total number of nucleons) in nuclear decay and reactions.

Problems & Exercises

1: The [latex]{\pi ^0}[/latex] is its own antiparticle and decays in the following manner: [latex]{\pi ^0 \rightarrow \gamma + \gamma}[/latex]. What is the energy of each [latex]{\gamma}[/latex] ray if the [latex]{\pi ^0}[/latex] is at rest when it decays?

2: The primary decay mode for the negative pion is [latex]{\pi ^- \rightarrow \mu ^- + \overline{\nu}_{\mu}}[/latex]. What is the energy release in MeV in this decay?

3: The mass of a theoretical particle that may be associated with the unification of the electroweak and strong forces is [latex]{10^{14} \;\text{GeV/c}^2}[/latex].

(a) How many proton masses is this?

(b) How many electron masses is this? (This indicates how extremely relativistic the accelerator would have to be in order to make the particle, and how large the relativistic quantity [latex]{\gamma}[/latex] would have to be.)

4: The decay mode of the negative muon is [latex]{\mu ^- \rightarrow e^- + \overline{\nu}_e + \nu _{\mu}}[/latex].

(a) Find the energy released in MeV.

(b) Verify that charge and lepton family numbers are conserved.

5: The decay mode of the positive tau is [latex]{\tau ^+ \rightarrow \mu ^+ + \nu _{\mu} + \overline{\nu}_{\tau}}[/latex].

(a) What energy is released?

(b) Verify that charge and lepton family numbers are conserved.

(c) The [latex]{\tau ^+}[/latex] is the antiparticle of the [latex]{\tau ^-}[/latex].Verify that all the decay products of the [latex]{\tau ^+}[/latex] are the antiparticles of those in the decay of the [latex]{\tau ^-}[/latex] given in the text.

6: The principal decay mode of the sigma zero is [latex]{\Sigma ^0 \rightarrow \Lambda ^0 + \lambda}[/latex].

(a) What energy is released?

(b) Considering the quark structure of the two baryons, does it appear that the [latex]{\Sigma ^0}[/latex] is an excited state of the [latex]{\Lambda ^0}[/latex]?

(c) Verify that strangeness, charge, and baryon number are conserved in the decay.

(d) Considering the preceding and the short lifetime, can the weak force be responsible? State why or why not.

7: (a) What is the uncertainty in the energy released in the decay of a [latex]{\pi ^0}[/latex] due to its short lifetime?

(b) What fraction of the decay energy is this, noting that the decay mode is [latex]{\pi ^0 \rightarrow \gamma + \gamma }[/latex] (so that all the [latex]{\pi ^0}[/latex] mass is destroyed)?

8: (a) What is the uncertainty in the energy released in the decay of a [latex]{\tau ^-}[/latex] due to its short lifetime?

(b) Is the uncertainty in this energy greater than or less than the uncertainty in the mass of the tau neutrino? Discuss the source of the uncertainty.

Footnotes

- 1 The lower of the [latex]{\mp}[/latex] or [latex]{\pm}[/latex] symbols are the values for antiparticles.

- 2 Lifetimes are traditionally given as [latex]{t_{1/2}/0.693}[/latex] (which is [latex]{1/ \lambda}[/latex], the inverse of the decay constant).

- 3 Neutrino masses may be zero. Experimental upper limits are given in parentheses.

- 4 Experimental lower limit is [latex]{>5 \times 10^{32}}[/latex] for proposed mode of decay.

Glossary

- boson

- particle with zero or an integer value of intrinsic spin

- baryons

- hadrons that always decay to another baryon

- baryon number

- a conserved physical quantity that is zero for mesons and leptons and [latex]{\pm}[/latex] for baryons and antibaryons, respectively

- conservation of total baryon number

- a general rule based on the observation that the total number of nucleons was always conserved in nuclear reactions and decays

- conservation of total electron family number

- a general rule stating that the total electron family number stays the same through an interaction

- conservation of total muon family number

- a general rule stating that the total muon family number stays the same through an interaction

- electron family number

- the number [latex]{\pm}[/latex] that is assigned to all members of the electron family, or the number 0 that is assigned to all particles not in the electron family

- fermion

- particle with a half-integer value of intrinsic spin

- gauge boson

- particle that carries one of the four forces

- hadrons

- particles that feel the strong nuclear force

- leptons

- particles that do not feel the strong nuclear force

- meson

- hadrons that can decay to leptons and leave no hadrons

- muon family number

- the number [latex]{\pm 1}[/latex] that is assigned to all members of the muon family, or the number 0 that is assigned to all particles not in the muon family

- strangeness

- a physical quantity assigned to various particles based on decay systematics

- tau family number

- the number [latex]{\pm 1}[/latex] that is assigned to all members of the tau family, or the number 0 that is assigned to all particles not in the tau family

Solutions

Problems & Exercises

1: 67.5 MeV

3: (a) [latex]{1 \times 10^{14}}[/latex]

(b) [latex]{2 \times 10^{17}}[/latex]

5: (a) 1671 MeV 1671 MeV

(b) [latex]{Q = 1 ,Q^{\prime} = 1+0+0 = 1}[/latex]. [latex]{L_{\tau} = -1 ; {L^{\prime}}_{\tau} = -1 ; L_{\mu} = 0; {L^{\prime}}_{\mu} = -1+1 = 0}[/latex]

(c)

[latex]{\tau ^- \rightarrow \mu ^- + v_{\mu} + \overline{v}_{\tau} \Rightarrow \mu ^- \;\text{antiparticle of} \;\mu^+ ; v_{\mu} \;\text{of} \;\overline{v}_{\mu} ; \overline{v}_{\tau} \;\text{of} \; v_{\tau}}[/latex]

7: (a) 3.9 eV

(b) [latex]{2.9 \times 10^{-8}}[/latex]