Chapter 17 Physics of Hearing

17.6 Hearing

Summary

- Define hearing, pitch, loudness, timbre, note, tone, phon, ultrasound, and infrasound.

- Compare loudness to frequency and intensity of a sound.

- Identify structures of the inner ear and explain how they relate to sound perception.

The human ear has a tremendous range and sensitivity. It can give us a wealth of simple information—such as pitch, loudness, and direction. And from its input we can detect musical quality and nuances of voiced emotion. How is our hearing related to the physical qualities of sound, and how does the hearing mechanism work?

Hearing is the perception of sound. (Perception is commonly defined to be awareness through the senses, a typically circular definition of higher-level processes in living organisms.) Normal human hearing encompasses frequencies from 20 to 20,000 Hz, an impressive range. Sounds below 20 Hz are called infrasound, whereas those above 20,000 Hz are ultrasound. Neither is perceived by the ear, although infrasound can sometimes be felt as vibrations. When we do hear low-frequency vibrations, such as the sounds of a diving board, we hear the individual vibrations only because there are higher-frequency sounds in each. Other animals have hearing ranges different from that of humans. Dogs can hear sounds as high as 30,000 Hz, whereas bats and dolphins can hear up to 100,000-Hz sounds. You may have noticed that dogs respond to the sound of a dog whistle which produces sound out of the range of human hearing. Elephants are known to respond to frequencies below 20 Hz.

The perception of frequency is called pitch. Most of us have excellent relative pitch, which means that we can tell whether one sound has a different frequency from another. Typically, we can discriminate between two sounds if their frequencies differ by 0.3% or more. For example, 500.0 and 501.5 Hz are noticeably different. Pitch perception is directly related to frequency and is not greatly affected by other physical quantities such as intensity. Musical notes are particular sounds that can be produced by most instruments and in Western music have particular names. Combinations of notes constitute music. Some people can identify musical notes, such as A-sharp, C, or E-flat, just by listening to them. This uncommon ability is called perfect pitch.

The ear is remarkably sensitive to low-intensity sounds. The lowest audible intensity or threshold is about [latex]{10^{-12}\text{ W/m}^2}[/latex] or 0 dB. Sounds as much as [latex]{10^{12}}[/latex] more intense can be briefly tolerated. Very few measuring devices are capable of observations over a range of a trillion. The perception of intensity is called loudness. At a given frequency, it is possible to discern differences of about 1 dB, and a change of 3 dB is easily noticed. But loudness is not related to intensity alone. Frequency has a major effect on how loud a sound seems. The ear has its maximum sensitivity to frequencies in the range of 2000 to 5000 Hz, so that sounds in this range are perceived as being louder than, say, those at 500 or 10,000 Hz, even when they all have the same intensity. Sounds near the high- and low-frequency extremes of the hearing range seem even less loud, because the ear is even less sensitive at those frequencies. Table 4 gives the dependence of certain human hearing perceptions on physical quantities.

| Perception | Physical quantity |

|---|---|

| Pitch | Frequency |

| Loudness | Intensity and Frequency |

| Timbre | Number and relative intensity of multiple frequencies. Subtle craftsmanship leads to non-linear effects and more detail. |

| Note | Basic unit of music with specific names, combined to generate tunes |

| Tone | Number and relative intensity of multiple frequencies. |

| Table 4. Sound Perceptions. | |

When a violin plays middle C, there is no mistaking it for a piano playing the same note. The reason is that each instrument produces a distinctive set of frequencies and intensities. We call our perception of these combinations of frequencies and intensities tone quality, or more commonly the timbre of the sound. It is more difficult to correlate timbre perception to physical quantities than it is for loudness or pitch perception. Timbre is more subjective. Terms such as dull, brilliant, warm, cold, pure, and rich are employed to describe the timbre of a sound. So the consideration of timbre takes us into the realm of perceptual psychology, where higher-level processes in the brain are dominant. This is true for other perceptions of sound, such as music and noise. We shall not delve further into them; rather, we will concentrate on the question of loudness perception.

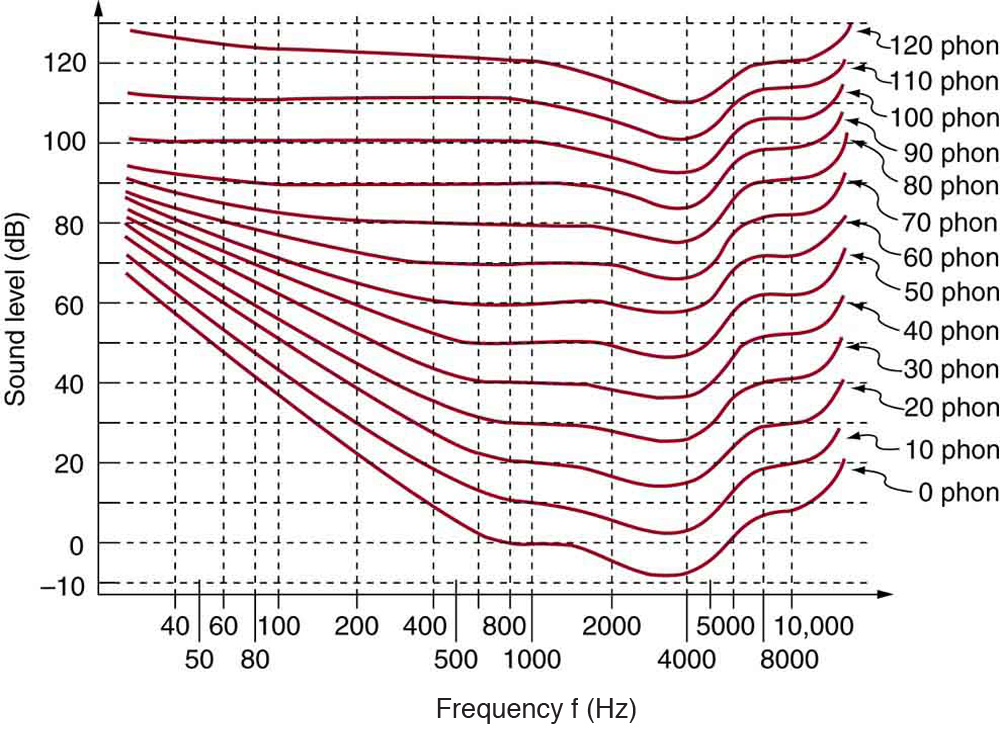

A unit called a phon is used to express loudness numerically. Phons differ from decibels because the phon is a unit of loudness perception, whereas the decibel is a unit of physical intensity. Figure 2 shows the relationship of loudness to intensity (or intensity level) and frequency for persons with normal hearing. The curved lines are equal-loudness curves. Each curve is labeled with its loudness in phons. Any sound along a given curve will be perceived as equally loud by the average person. The curves were determined by having large numbers of people compare the loudness of sounds at different frequencies and sound intensity levels. At a frequency of 1000 Hz, phons are taken to be numerically equal to decibels. The following example helps illustrate how to use the graph:

Example 1: Measuring Loudness: Loudness Versus Intensity Level and Frequency

(a) What is the loudness in phons of a 100-Hz sound that has an intensity level of 80 dB? (b) What is the intensity level in decibels of a 4000-Hz sound having a loudness of 70 phons? (c) At what intensity level will an 8000-Hz sound have the same loudness as a 200-Hz sound at 60 dB?

Strategy for (a)

The graph in Figure 2 should be referenced in order to solve this example. To find the loudness of a given sound, you must know its frequency and intensity level and locate that point on the square grid, then interpolate between loudness curves to get the loudness in phons.

Solution for (a)

(1) Identify knowns:

- The square grid of the graph relating phons and decibels is a plot of intensity level versus frequency—both physical quantities.

- 100 Hz at 80 dB lies halfway between the curves marked 70 and 80 phons.

(2) Find the loudness: 75 phons.

Strategy for (b)

The graph in Figure 2 should be referenced in order to solve this example. To find the intensity level of a sound, you must have its frequency and loudness. Once that point is located, the intensity level can be determined from the vertical axis.

Solution for (b)

(1) Identify knowns:

- Values are given to be 4000 Hz at 70 phons.

(2) Follow the 70-phon curve until it reaches 4000 Hz. At that point, it is below the 70 dB line at about 67 dB.

(3) Find the intensity level:

67 dB

Strategy for (c)

The graph in Figure 2 should be referenced in order to solve this example.

Solution for (c)

(1) Locate the point for a 200 Hz and 60 dB sound.

(2) Find the loudness: This point lies just slightly above the 50-phon curve, and so its loudness is 51 phons.

(3) Look for the 51-phon level is at 8000 Hz: 63 dB.

Discussion

These answers, like all information extracted from Figure 2, have uncertainties of several phons or several decibels, partly due to difficulties in interpolation, but mostly related to uncertainties in the equal-loudness curves.

Further examination of the graph in Figure 2 reveals some interesting facts about human hearing. First, sounds below the 0-phon curve are not perceived by most people. So, for example, a 60 Hz sound at 40 dB is inaudible. The 0-phon curve represents the threshold of normal hearing. We can hear some sounds at intensity levels below 0 dB. For example, a 3-dB, 5000-Hz sound is audible, because it lies above the 0-phon curve. The loudness curves all have dips in them between about 2000 and 5000 Hz. These dips mean the ear is most sensitive to frequencies in that range. For example, a 15-dB sound at 4000 Hz has a loudness of 20 phons, the same as a 20-dB sound at 1000 Hz. The curves rise at both extremes of the frequency range, indicating that a greater-intensity level sound is needed at those frequencies to be perceived to be as loud as at middle frequencies. For example, a sound at 10,000 Hz must have an intensity level of 30 dB to seem as loud as a 20 dB sound at 1000 Hz. Sounds above 120 phons are painful as well as damaging.

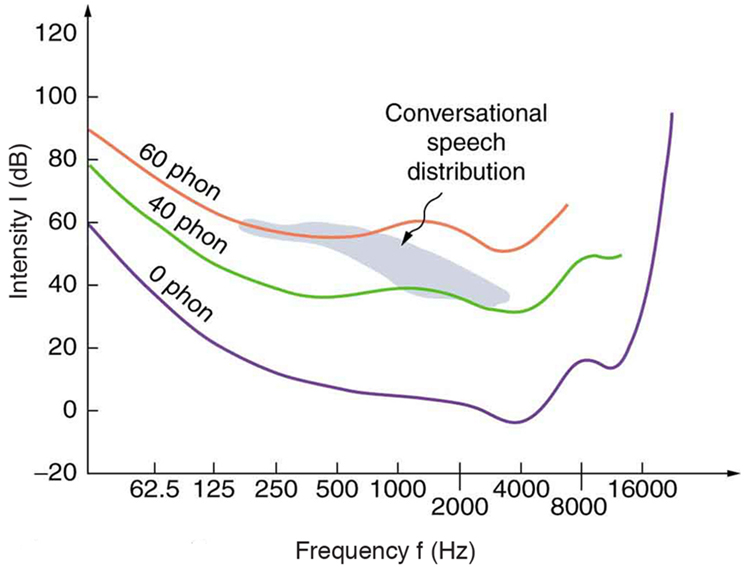

We do not often utilize our full range of hearing. This is particularly true for frequencies above 8000 Hz, which are rare in the environment and are unnecessary for understanding conversation or appreciating music. In fact, people who have lost the ability to hear such high frequencies are usually unaware of their loss until tested. The shaded region in Figure 3 is the frequency and intensity region where most conversational sounds fall. The curved lines indicate what effect hearing losses of 40 and 60 phons will have. A 40-phon hearing loss at all frequencies still allows a person to understand conversation, although it will seem very quiet. A person with a 60-phon loss at all frequencies will hear only the lowest frequencies and will not be able to understand speech unless it is much louder than normal. Even so, speech may seem indistinct, because higher frequencies are not as well perceived. The conversational speech region also has a gender component, in that female voices are usually characterized by higher frequencies. So the person with a 60-phon hearing impediment might have difficulty understanding the normal conversation of a woman.

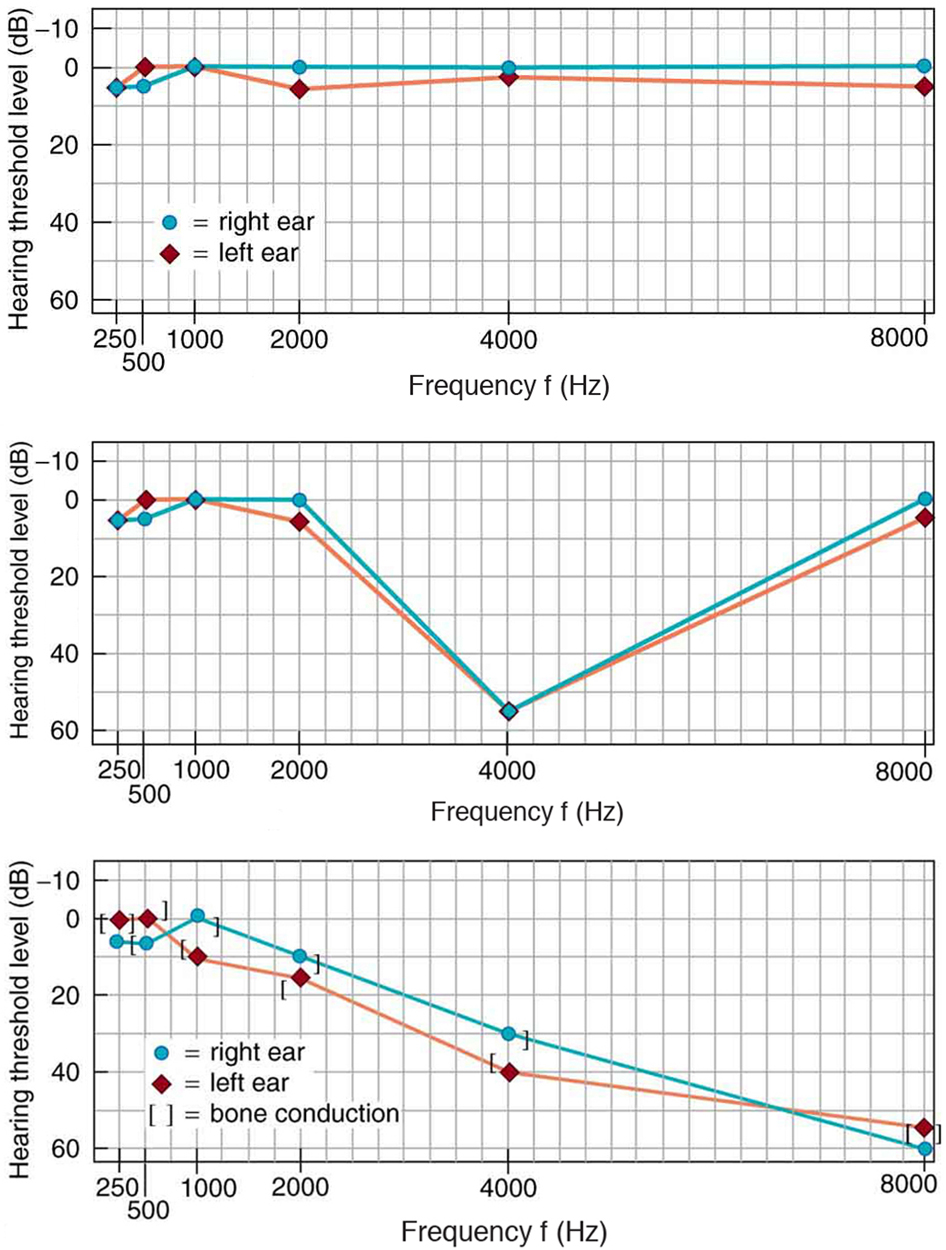

Hearing tests are performed over a range of frequencies, usually from 250 to 8000 Hz, and can be displayed graphically in an audiogram like that in Figure 4. The hearing threshold is measured in dB relative to the normal threshold, so that normal hearing registers as 0 dB at all frequencies. Hearing loss caused by noise typically shows a dip near the 4000 Hz frequency, irrespective of the frequency that caused the loss and often affects both ears. The most common form of hearing loss comes with age and is called presbycusis—literally elder ear. Such loss is increasingly severe at higher frequencies, and interferes with music appreciation and speech recognition.

The Hearing Mechanism

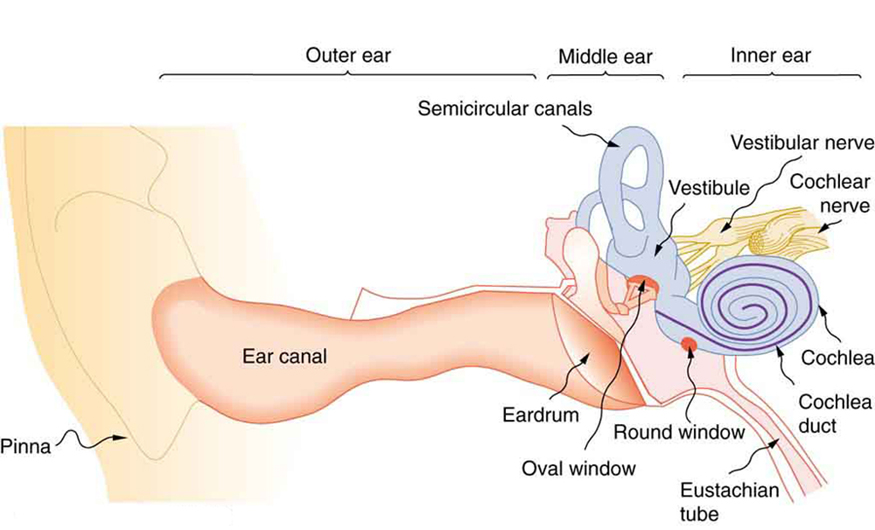

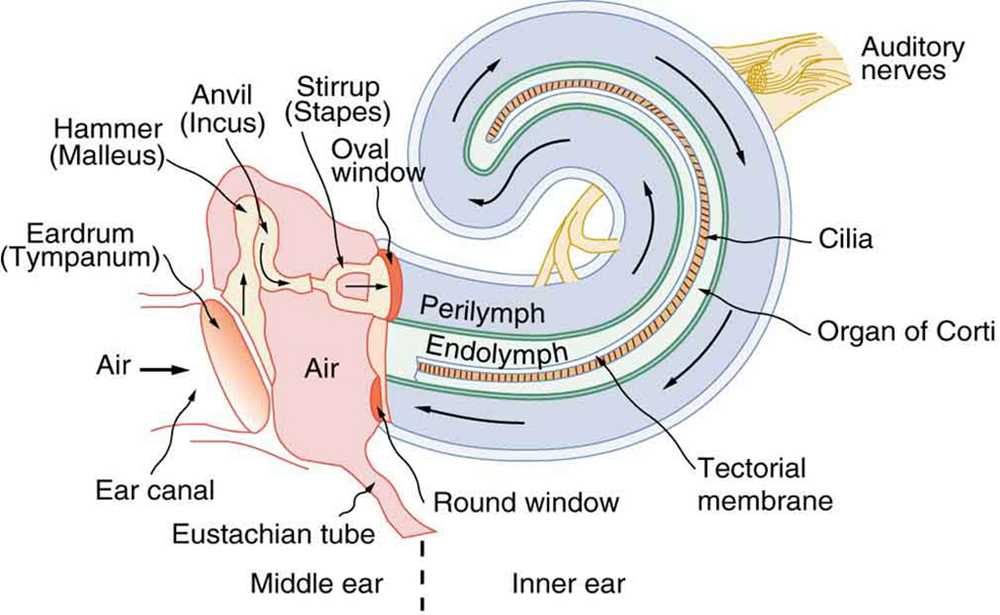

The hearing mechanism involves some interesting physics. The sound wave that impinges upon our ear is a pressure wave. The ear is a transducer that converts sound waves into electrical nerve impulses in a manner much more sophisticated than, but analogous to, a microphone. Figure 5. shows the gross anatomy of the ear with its division into three parts: the outer ear or ear canal; the middle ear, which runs from the eardrum to the cochlea; and the inner ear, which is the cochlea itself. The body part normally referred to as the ear is technically called the pinna.

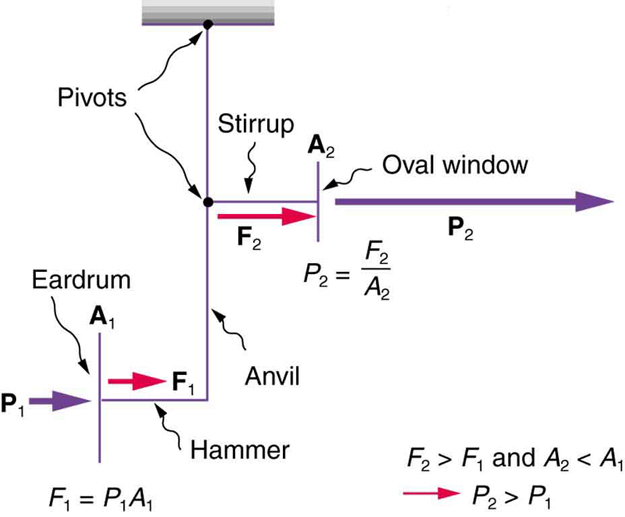

The outer ear, or ear canal, carries sound to the recessed protected eardrum. The air column in the ear canal resonates and is partially responsible for the sensitivity of the ear to sounds in the 2000 to 5000 Hz range. The middle ear converts sound into mechanical vibrations and applies these vibrations to the cochlea. The lever system of the middle ear takes the force exerted on the eardrum by sound pressure variations, amplifies it and transmits it to the inner ear via the oval window, creating pressure waves in the cochlea approximately 40 times greater than those impinging on the eardrum. (See Figure 6.) Two muscles in the middle ear (not shown) protect the inner ear from very intense sounds. They react to intense sound in a few milliseconds and reduce the force transmitted to the cochlea. This protective reaction can also be triggered by your own voice, so that humming while shooting a gun, for example, can reduce noise damage.

Figure 7 shows the middle and inner ear in greater detail. Pressure waves moving through the cochlea cause the tectorial membrane to vibrate, rubbing cilia (called hair cells), which stimulate nerves that send electrical signals to the brain. The membrane resonates at different positions for different frequencies, with high frequencies stimulating nerves at the near end and low frequencies at the far end. The complete operation of the cochlea is still not understood, but several mechanisms for sending information to the brain are known to be involved. For sounds below about 1000 Hz, the nerves send signals at the same frequency as the sound. For frequencies greater than about 1000 Hz, the nerves signal frequency by position. There is a structure to the cilia, and there are connections between nerve cells that perform signal processing before information is sent to the brain. Intensity information is partly indicated by the number of nerve signals and by volleys of signals. The brain processes the cochlear nerve signals to provide additional information such as source direction (based on time and intensity comparisons of sounds from both ears). Higher-level processing produces many nuances, such as music appreciation.

Hearing losses can occur because of problems in the middle or inner ear. Conductive losses in the middle ear can be partially overcome by sending sound vibrations to the cochlea through the skull. Hearing aids for this purpose usually press against the bone behind the ear, rather than simply amplifying the sound sent into the ear canal as many hearing aids do. Damage to the nerves in the cochlea is not repairable, but amplification can partially compensate. There is a risk that amplification will produce further damage. Another common failure in the cochlea is damage or loss of the cilia but with nerves remaining functional. Cochlear implants that stimulate the nerves directly are now available and widely accepted. Over 100,000 implants are in use, in about equal numbers of adults and children.

The cochlear implant was pioneered in Melbourne, Australia, by Graeme Clark in the 1970s for his deaf father. The implant consists of three external components and two internal components. The external components are a microphone for picking up sound and converting it into an electrical signal, a speech processor to select certain frequencies and a transmitter to transfer the signal to the internal components through electromagnetic induction. The internal components consist of a receiver/transmitter secured in the bone beneath the skin, which converts the signals into electric impulses and sends them through an internal cable to the cochlea and an array of about 24 electrodes wound through the cochlea. These electrodes in turn send the impulses directly into the brain. The electrodes basically emulate the cilia.

Check Your Understanding

1: Are ultrasound and infrasound imperceptible to all hearing organisms? Explain your answer.

Section Summary

- The range of audible frequencies is 20 to 20,000 Hz.

- Those sounds above 20,000 Hz are ultrasound, whereas those below 20 Hz are infrasound.

- The perception of frequency is pitch.

- The perception of intensity is loudness.

- Loudness has units of phons.

Conceptual Questions

1: Why can a hearing test show that your threshold of hearing is 0 dB at 250 Hz, when Figure 3 implies that no one can hear such a frequency at less than 20 dB?

Problems & Exercises

1: The factor of [latex]{10^{-12}}[/latex] in the range of intensities to which the ear can respond, from threshold to that causing damage after brief exposure, is truly remarkable. If you could measure distances over the same range with a single instrument and the smallest distance you could measure was 1 mm, what would the largest be?

2: The frequencies to which the ear responds vary by a factor of [latex]{10^3}.[/latex] Suppose the speedometer on your car measured speeds differing by the same factor of [latex]{10^3},[/latex] and the greatest speed it reads is 90.0 mi/h. What would be the slowest nonzero speed it could read?

3: What are the closest frequencies to 500 Hz that an average person can clearly distinguish as being different in frequency from 500 Hz? The sounds are not present simultaneously.

4: Can the average person tell that a 2002-Hz sound has a different frequency than a 1999-Hz sound without playing them simultaneously?

5: If your radio is producing an average sound intensity level of 85 dB, what is the next lowest sound intensity level that is clearly less intense?

6: Can you tell that your roommate turned up the sound on the TV if its average sound intensity level goes from 70 to 73 dB?

7: Based on the graph in Figure 2, what is the threshold of hearing in decibels for frequencies of 60, 400, 1000, 4000, and 15,000 Hz? Note that many AC electrical appliances produce 60 Hz, music is commonly 400 Hz, a reference frequency is 1000 Hz, your maximum sensitivity is near 4000 Hz, and many older TVs produce a 15,750 Hz whine.

8: What sound intensity levels must sounds of frequencies 60, 3000, and 8000 Hz have in order to have the same loudness as a 40-dB sound of frequency 1000 Hz (that is, to have a loudness of 40 phons)?

9: What is the approximate sound intensity level in decibels of a 600-Hz tone if it has a loudness of 20 phons? If it has a loudness of 70 phons?

1): (a) What are the loudnesses in phons of sounds having frequencies of 200, 1000, 5000, and 10,000 Hz, if they are all at the same 60.0-dB sound intensity level? (b) If they are all at 110 dB? (c) If they are all at 20.0 dB?

11: Suppose a person has a 50-dB hearing loss at all frequencies. By how many factors of 10 will low-intensity sounds need to be amplified to seem normal to this person? Note that smaller amplification is appropriate for more intense sounds to avoid further hearing damage.

12: If a woman needs an amplification of [latex]{5.0\times10^{12}}[/latex] times the threshold intensity to enable her to hear at all frequencies, what is her overall hearing loss in dB? Note that smaller amplification is appropriate for more intense sounds to avoid further damage to her hearing from levels above 90 dB.

13: (a) What is the intensity in watts per meter squared of a just barely audible 200-Hz sound? (b) What is the intensity in watts per meter squared of a barely audible 4000-Hz sound?

14: (a) Find the intensity in watts per meter squared of a 60.0-Hz sound having a loudness of 60 phons. (b) Find the intensity in watts per meter squared of a 10,000-Hz sound having a loudness of 60 phons.

15: A person has a hearing threshold 10 dB above normal at 100 Hz and 50 dB above normal at 4000 Hz. How much more intense must a 100-Hz tone be than a 4000-Hz tone if they are both barely audible to this person?

16: A child has a hearing loss of 60 dB near 5000 Hz, due to noise exposure, and normal hearing elsewhere. How much more intense is a 5000-Hz tone than a 400-Hz tone if they are both barely audible to the child?

17: What is the ratio of intensities of two sounds of identical frequency if the first is just barely discernible as louder to a person than the second?

Glossary

- loudness

- the perception of sound intensity

- timbre

- number and relative intensity of multiple sound frequencies

- note

- basic unit of music with specific names, combined to generate tunes

- tone

- number and relative intensity of multiple sound frequencies

- phon

- the numerical unit of loudness

- ultrasound

- sounds above 20,000 Hz

- infrasound

- sounds below 20 Hz

Solutions

Check Your understanding

1: No, the range of perceptible sound is based in the range of human hearing. Many other organisms perceive either infrasound or ultrasound.

Problems & Exercises

1:

[latex]{1\times10^6\text{ km}}[/latex]

3:

498.5 or 501.5 Hz

5:

82 dB

7:

approximately 48, 9, 0, –7, and 20 dB, respectively

9:

(a) 23 dB

(b) 70 dB

11:

Five factors of 10

13:

(a) [latex]{2\times10^{-10}\text{ W/m}^2}[/latex]

(b) [latex]{2\times10^{-13}\text{ W/m}^2}[/latex]

15:

2.5

17:

1.26