44.4 Aquatic Biomes

Learning Objectives

- Describe the effects of abiotic factors on the composition of plant and animal communities in aquatic biomes

- Compare and contrast the characteristics of the ocean zones

- Summarize the characteristics of standing water and flowing water freshwater biomes

Abiotic Factors Influencing Aquatic Biomes

Like terrestrial biomes, aquatic biomes are influenced by a series of abiotic factors. The aquatic medium—water— has different physical and chemical properties than air, however. Even if the water in a pond or other body of water is perfectly clear (there are no suspended particles), water, on its own, absorbs light. As one descends into a deep body of water, there will eventually be a depth which the sunlight cannot reach. While there are some abiotic and biotic factors in a terrestrial ecosystem that might obscure light (like fog, dust, or insect swarms), usually these are not permanent features of the environment. The importance of light in aquatic biomes is central to the communities of organisms found in both freshwater and marine ecosystems. In freshwater systems, stratification due to differences in density is perhaps the most critical abiotic factor and is related to the energy aspects of light. The thermal properties of water (rates of heating and cooling and the ability to store much larger amounts of energy than the air) are significant to the function of marine systems and have major impacts on global climate and weather patterns. Marine systems are also influenced by large-scale physical water movements, such as currents; these are less important in most freshwater lakes.

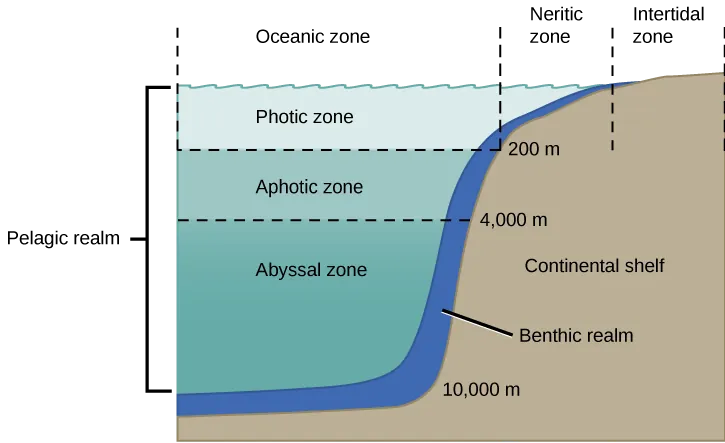

The ocean is categorized by several areas or zones (Figure 44.21). All of the ocean’s open water is referred to as the pelagic realm (or zone). The benthic realm (or zone) extends along the ocean bottom from the shoreline to the deepest parts of the ocean floor. Within the pelagic realm is the photic zone, which is the portion of the ocean that light can penetrate (approximately 200 m or 650 ft). At depths greater than 200 m, light cannot penetrate; thus, this is referred to as the aphotic zone. The majority of the ocean is aphotic and lacks sufficient light for photosynthesis.

Visual Connection

Marine Biomes

The ocean is the largest marine biome. It is a continuous body of salt water that is relatively uniform in chemical composition; in fact, it is a weak solution of mineral salts and decayed biological matter. Within the ocean, coral reefs are a second kind of marine biome. Estuaries, coastal areas where salt water and fresh water mix, form a third unique marine biome.

Ocean

The physical diversity of the ocean is a significant influence on plants, animals, and other organisms. The ocean is categorized into different zones based on how far light reaches into the water. Each zone has a distinct group of species adapted to the biotic and abiotic conditions particular to that zone.

The intertidal zone, which is the zone between high and low tide, is the oceanic region that is closest to land (Figure 44.21). The intertidal zone is an extremely variable environment because of action of tidal ebb and flow. Organisms are exposed to air and sunlight at low tide and are underwater most of the time, especially during high tide. Therefore, living things that thrive in the intertidal zone are adapted to being dry for long periods of time. The shore of the intertidal zone may also be repeatedly struck by waves, and the organisms found there are adapted to withstand damage from their pounding action (Figure 44.22).

The neritic zone (Figure 44.21) extends from the intertidal zone to depths of about 200 m (or 650 ft) at the edge of the continental shelf (the underwater landmass that extends from a continent). Since light can penetrate this depth, photosynthesis can still occur in the neritic zone. Zooplankton, protists, small fishes, and shrimp are found in the neritic zone and are the base of the food chain for most of the world’s fisheries.

Beyond the neritic zone is the open ocean area known as the pelagic or open oceanic zone (Figure 44.21). Within the oceanic zone there is thermal stratification where warm and cold waters mix because of ocean currents. Abundant plankton serve as the base of the food chain for larger animals such as whales and dolphins. Nutrients are scarce and this is a relatively less productive part of the marine biome. When photosynthetic organisms and the protists and animals that feed on them die, their bodies fall to the bottom of the ocean, where they remain.

Beneath the pelagic zone is the benthic realm. (Figure 44.21). The bottom of the benthic realm is composed of sand, silt, and dead organisms. Temperature decreases, remaining above freezing, as water depth increases. This is a nutrient-rich portion of the ocean because of the dead organisms that fall from the upper layers of the ocean. Because of this high level of nutrients, a diversity of fungi, sponges, sea anemones, marine worms, sea stars, fishes, and bacteria exist.

The deepest part of the ocean is the abyssal zone, which is at depths of 4000 m or greater. The abyssal zone (Figure 44.21) is very cold and has very high pressure, high oxygen content, and low nutrient content. There are a variety of invertebrates and fishes found in this zone, but the abyssal zone does not have plants because of the lack of light. Hydrothermal vents are found primarily in the abyssal zone; chemosynthetic bacteria utilize the hydrogen sulfide and other minerals emitted from the vents. These chemosynthetic bacteria use the hydrogen sulfide as an energy source and serve as the base of the food chain found in the abyssal zone.

Coral Reefs

Coral reefs are geological structures formed by marine invertebrates, comprising mostly cnidarians and molluscs, living in warm shallow waters within the photic zone of the ocean. They are found within 30˚ north and south of the equator. The coral organisms (members of phylum Cnidaria) are colonies of saltwater polyps that secrete a calcium carbonate skeleton. These calcium-rich skeletons slowly accumulate, forming the underwater reef (Figure 44.23). Coral reefs support a high diversity of invertebrates and vertebrates such as fish and marine reptiles.

Estuaries: Where the Ocean Meets Fresh Water

Estuaries are biomes that occur where a source of fresh water, such as a river, meets the ocean. Therefore, both fresh water and salt water are found in the same vicinity; mixing results in a diluted (brackish) saltwater. Estuaries form protected areas where many of the young offspring of crustaceans, molluscs, and fish begin their lives, which also creates important breeding grounds for other animals. Salinity is a very important factor that influences the organisms and the adaptations of the organisms found in estuaries. The salinity of estuaries varies considerably and is based on the rate of flow of its freshwater sources, which may depend on the seasonal rainfall. Once or twice a day, high tides bring salt water into the estuary. Low tides occurring at the same frequency reverse the current of salt water. The variance in salinity requires estuarine organisms to have adaptations to handle the changes. Biomass is generally high in estuaries due to high nutrient levels but the harsher conditions limit species diversity.

Freshwater Biomes

Freshwater biomes include lakes and ponds (standing water) as well as rivers and streams (flowing water). They also include wetlands, which will be discussed later. Humans rely on freshwater biomes to provide ecosystem benefits, which are aquatic resources for drinking water, crop irrigation, sanitation, and industry. Lakes and ponds are connected with abiotic and biotic factors influencing their terrestrial biomes.

Lakes and Ponds

Lakes and ponds can range in area from a few square meters to thousands of square kilometers. Temperature is an important abiotic factor affecting living things found in lakes and ponds. In the summer, as we have seen, thermal stratification of lakes and ponds occurs when the upper layer of water is warmed by the sun and does not mix with deeper, cooler water. Light can penetrate within the photic zone of the lake or pond. Phytoplankton (algae and cyanobacteria) are found here and carry out photosynthesis, providing the base of the food web of lakes and ponds. Zooplankton, such as rotifers and larvae and adult crustaceans, consume these phytoplankton. At the bottom of lakes and ponds, bacteria in the aphotic zone break down dead organisms that sink to the bottom.

Nitrogen and phosphorus are important limiting nutrients in lakes and ponds. Because of this, they are the determining factors in the amount of phytoplankton growth that takes place in lakes and ponds. When there is a large input of nitrogen and phosphorus (from sewage and runoff from fertilized lawns and farms, for example), the growth of algae skyrockets, resulting in a large accumulation of algae called an algal bloom.

Rivers and Streams

Rivers and streams are continuously moving bodies of water that carry large amounts of water from the source, or headwater, to a lake or ocean. The largest rivers include the Nile River in Africa, the Amazon River in South America, and the Mississippi River in North America.

Abiotic features of rivers and streams vary along the length of the river or stream. The fast-moving water results in minimal silt accumulation at the bottom of the river or stream; therefore, the water is usually clear and free of debris. Photosynthesis here is mostly attributed to algae that are growing on rocks; the swift current inhibits the growth of phytoplankton. An additional input of energy can come from leaves and other organic material that fall downstream into the river or stream, as well as from trees and other plants that border the water. Plants and animals have adapted to this fast-moving water.

As the river or stream flows away from the source, the width of the channel gradually widens and the current slows. This slow-moving water, caused by the gradient decrease and the volume increase as tributaries unite, has more sedimentation. Phytoplankton can also be suspended in slow-moving water. Therefore, the water will not be as clear as it is near the source, and the water is also warmer.

Wetlands

Wetlands are environments in which the soil is either permanently or periodically saturated with water. Wetlands are different from lakes because wetlands are shallow bodies of water whereas lakes vary in depth. Emergent vegetation consists of wetland plants that are rooted in the soil but have portions of leaves, stems, and flowers extending above the water’s surface. There are several types of wetlands including marshes, swamps, bogs, mudflats, and salt marshes (Figure 44.25). The three shared characteristics among these types—what makes them wetlands—are their hydrology, hydrophytic vegetation, and hydric soils.

Link to Learning

Watch this summary video on aquatic biomes.