46.3 Biogeochemical Cycles

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the biogeochemical cycles of water and carbon

Energy flows directionally through ecosystems, entering as sunlight (or inorganic molecules for chemoautotrophs) and leaving as heat during the many transfers between trophic levels. However, the matter that makes up living organisms is conserved and recycled. The six most common elements associated with organic molecules—carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, phosphorus, and sulfur—take a variety of chemical forms and may exist for long periods in the atmosphere, on land, in water, or beneath the Earth’s surface. Geologic processes, such as weathering, erosion, water drainage, and the subduction of the continental plates, all play a role in this recycling of materials. Because geology and chemistry have major roles in the study of this process, the recycling of inorganic matter between living organisms and their environment is called a biogeochemical cycle.

Water contains hydrogen and oxygen, which is essential to all living processes. The hydrosphere is the area of the Earth where water movement and storage occurs. On or beneath the surface, water occurs in liquid or solid form in rivers, lakes, oceans, groundwater, polar ice caps, and glaciers. And it occurs as water vapor in the atmosphere. Carbon is found in all organic macromolecules and is an important constituent of fossil fuels. Nitrogen is a major component of our nucleic acids and proteins and is critical to human agriculture. Phosphorus, a major component of nucleic acid (along with nitrogen), is one of the main ingredients in artificial fertilizers used in agriculture and their associated environmental impacts on our surface water. Sulfur is critical to the 3-D folding of proteins, such as in disulfide binding.

The cycling of these elements is interconnected. For example, the movement of water is critical for the leaching of nitrogen and phosphate into rivers, lakes, and oceans. Furthermore, the ocean itself is a major reservoir for carbon. Thus, mineral nutrients are cycled, either rapidly or slowly, through the entire biosphere, from one living organism to another, and between the biotic and abiotic world.

The Water (Hydrologic) Cycle

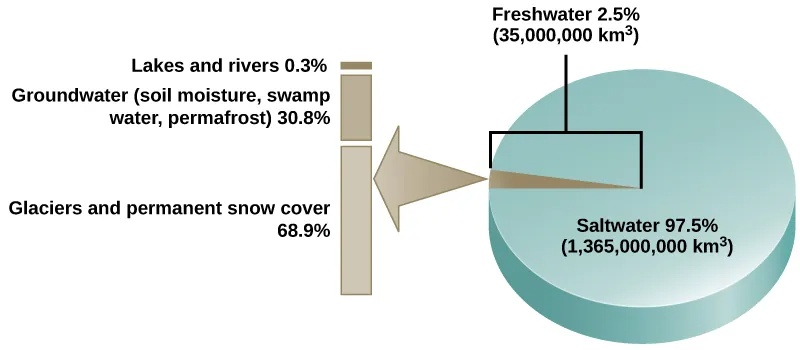

Water is the basis of all living processes on Earth. When examining the stores of water on Earth, 97.5 percent of it is non-potable salt water (Figure 46.12). Of the remaining water, 99 percent is locked underground as water or as ice. Thus, less than 1 percent of fresh water is easily accessible from lakes and rivers. Many living things, such as plants, animals, and fungi, are dependent on that small amount of fresh surface water, a lack of which can have massive effects on ecosystem dynamics. To be successful, organisms must adapt to fluctuating water supplies. Humans, of course, have developed technologies to increase water availability, such as digging wells to harvest groundwater, storing rainwater, and using desalination to obtain drinkable water from the ocean.

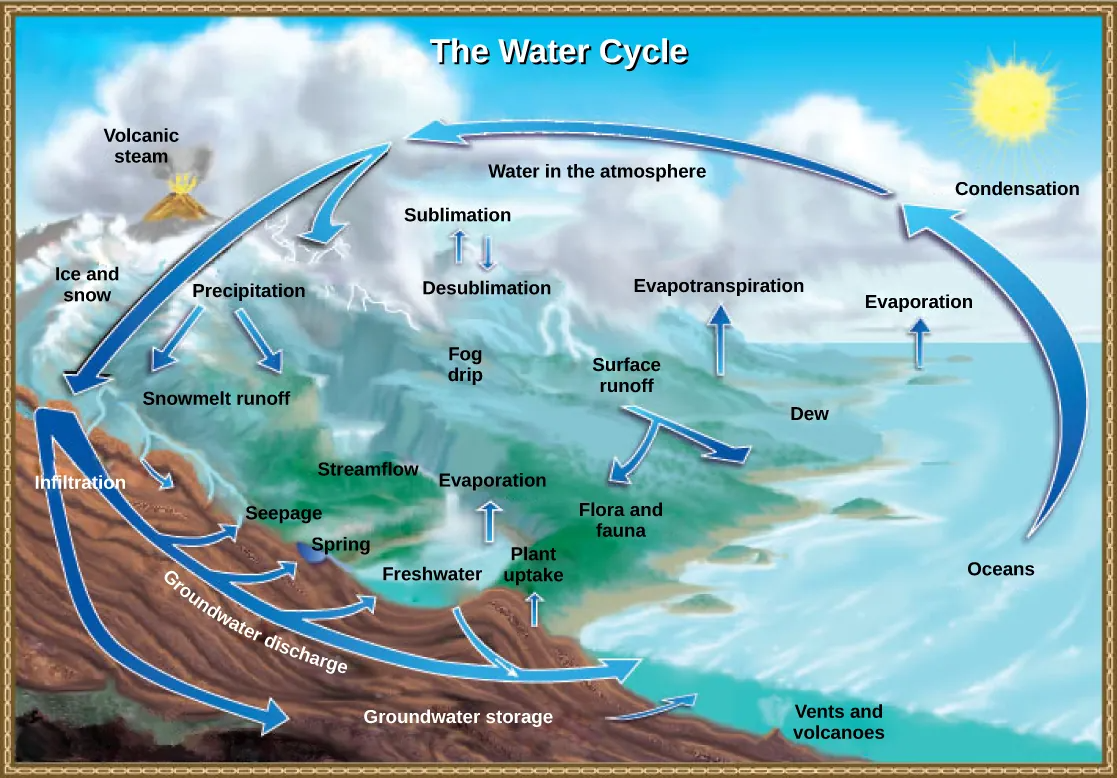

There are various processes that occur during the cycling of water, shown in Figure 46.14 These processes include the following:

- evaporation/sublimation

- condensation/precipitation

- subsurface water flow

- surface runoff/snowmelt

- streamflow

The water cycle is driven by the sun’s energy as it warms the oceans and other surface waters. This leads to the evaporation (water to water vapor) of liquid surface water and the sublimation (ice to water vapor) of frozen water, which deposits large amounts of water vapor into the atmosphere. Over time, this water vapor condenses into clouds as liquid or frozen droplets and is eventually followed by precipitation (rain or snow), which returns water to the Earth’s surface. Rain eventually permeates into the ground, where it may evaporate again if it is near the surface, flow beneath the surface, or be stored for long periods. More easily observed is surface runoff: the flow of fresh water either from rain or melting ice. Runoff can then make its way through streams and lakes to the oceans or flow directly to the oceans themselves.

Link to Learning

Head to this website to learn more about the world’s fresh water supply.

Rain and surface runoff are major ways in which minerals, including carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur, are cycled from land to water. The environmental effects of runoff will be discussed later as these cycles are described.

The Carbon Cycle

Carbon is the second most abundant element in living organisms. Carbon is present in all organic molecules, and its role in the structure of macromolecules is of primary importance to living organisms.

The carbon cycle is most easily studied as two interconnected sub-cycles: one dealing with rapid carbon exchange among living organisms and the other dealing with the long-term cycling of carbon through geologic processes. The entire carbon cycle is shown in Figure 46.15..

Link to Learning

Click this link to read information about the United States Carbon Cycle Science Program

The Biological Carbon Cycle

Living organisms are connected in many ways, even between ecosystems. A good example of this connection is the exchange of carbon between autotrophs and heterotrophs within and between ecosystems by way of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide is the basic building block that most autotrophs use to build multicarbon, high energy compounds, such as glucose. The energy harnessed from the sun is used by these organisms to form the covalent bonds that link carbon atoms together. These chemical bonds thereby store this energy for later use in the process of respiration. Most terrestrial autotrophs obtain their carbon dioxide directly from the atmosphere, while marine autotrophs acquire it in the dissolved form (carbonic acid, H2CO3−). However carbon dioxide is acquired, a by-product of the process is oxygen. The photosynthetic organisms are responsible for depositing approximately 21 percent oxygen content of the atmosphere that we observe today.

Heterotrophs and autotrophs are partners in biological carbon exchange (especially the primary consumers, largely herbivores). Heterotrophs acquire the high-energy carbon compounds from the autotrophs by consuming them, and breaking them down by respiration to obtain cellular energy, such as ATP. The most efficient type of respiration, aerobic respiration, requires oxygen obtained from the atmosphere or dissolved in water. Thus, there is a constant exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between the autotrophs (which need the carbon) and the heterotrophs (which need the oxygen). Gas exchange through the atmosphere and water is one way that the carbon cycle connects all living organisms on Earth.

The Biogeochemical Carbon Cycle

The movement of carbon through the land, water, and air is complex, and in many cases, it occurs much more slowly geologically than as seen between living organisms. Carbon is stored for long periods in what are known as carbon reservoirs, which include the atmosphere, bodies of liquid water (mostly oceans), ocean sediment, soil, land sediments (including fossil fuels), and the Earth’s interior.

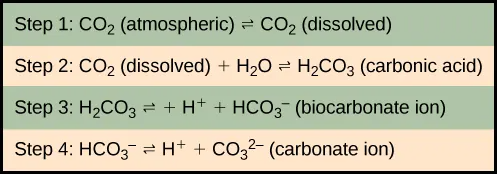

As stated, the atmosphere is a major reservoir of carbon in the form of carbon dioxide and is essential to the process of photosynthesis. The level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is greatly influenced by the reservoir of carbon in the oceans. The exchange of carbon between the atmosphere and water reservoirs influences how much carbon is found in each location, and each one affects the other reciprocally. Carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere dissolves in water and combines with water molecules to form carbonic acid, and then it ionizes to carbonate and bicarbonate ions (Figure 46.16)

The equilibrium coefficients are such that more than 90 percent of the carbon in the ocean is found as bicarbonate ions. Some of these ions combine with seawater calcium to form calcium carbonate (CaCO3), a major component of marine organism shells. These organisms eventually form sediments on the ocean floor. Over geologic time, the calcium carbonate forms limestone, which comprises the largest carbon reservoir on Earth.

On land, carbon is stored in soil as a result of the decomposition of living organisms (by decomposers) or from weathering of terrestrial rock and minerals. This carbon can be leached into the water reservoirs by surface runoff. Deeper underground, on land and at sea, are fossil fuels: the anaerobically decomposed remains of plants that take millions of years to form. Fossil fuels are considered a nonrenewable resource because their use far exceeds their rate of formation. A nonrenewable resource, such as fossil fuel, is either regenerated very slowly or not at all. Another way for carbon to enter the atmosphere is from land (including land beneath the surface of the ocean) by the eruption of volcanoes and other geothermal systems. Carbon sediments from the ocean floor are taken deep within the Earth by the process of subduction: the movement of one tectonic plate beneath another. Carbon is released as carbon dioxide when a volcano erupts or from volcanic hydrothermal vents.

Humans contribute to atmospheric carbon by the burning of fossil fuels and other materials. Since the Industrial Revolution, humans have significantly increased the release of carbon and carbon compounds, which has in turn affected the climate and overall environment.

Animal husbandry by humans also increases atmospheric carbon. The large numbers of land animals raised to feed the Earth’s growing population results in increased carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere due to farming practices and respiration and methane production. This is another example of how human activity indirectly affects biogeochemical cycles in a significant way. Although much of the debate about the future effects of increasing atmospheric carbon on climate change focuses on fossils fuels, scientists take natural processes, such as volcanoes and respiration, into account as they model and predict the future impact of this increase.