22.2 Structure of Prokaryotes

Learning Outcomes

- Describe the basic structure of a typical prokaryote

- Describe how prokaryotes reproduce and genetically recombine

There are many differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. The name “prokaryote” suggests that prokaryotes are defined by exclusion—they are not eukaryotes, or organisms whose cells contain a nucleus and other internal membrane-bound organelles. However, all cells have four common structures:

- the plasma membrane, which functions as a barrier for the cell and separates the cell from its environment;

- the cytoplasm, a complex solution of organic molecules and salts inside the cell;

- a double-stranded DNA genome, the informational archive of the cell;

- ribosomes, where protein synthesis takes place.

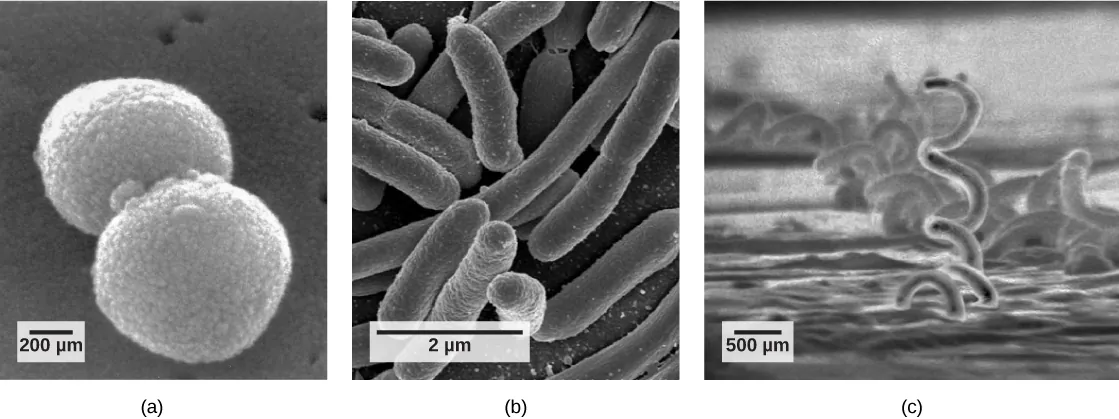

Prokaryotes come in various shapes, but many fall into three categories: cocci (spherical), bacilli (rod-shaped), and spirilli (spiral-shaped) (Figure 22.9).

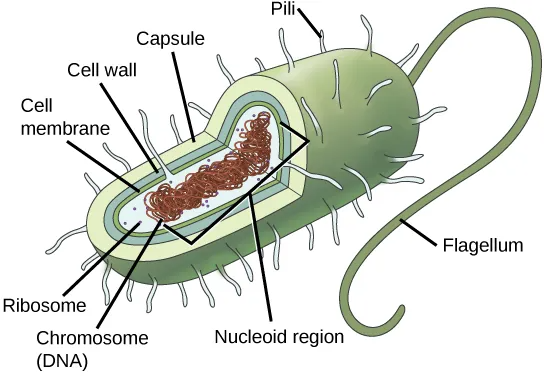

The Prokaryotic Cell

Recall that prokaryotes are unicellular organisms that lack membrane-bound organelles or other internal membrane-bound structures (Figure 22.10). Their chromosome—usually single—consists of a piece of circular, double-stranded DNA located in an area of the cell called the nucleoid. Most prokaryotes have a cell wall outside the plasma membrane. The cell wall functions as a protective layer, and it is responsible for the organism’s shape. Some bacterial species have a capsule outside the cell wall. The capsule enables the organism to attach to surfaces, protects it from dehydration and attack by phagocytic cells, and makes pathogens more resistant to our immune responses. Some species also have flagella (singular, flagellum) used for locomotion, and pili (singular, pilus) used for attachment to surfaces including the surfaces of other cells. Plasmids, which consist of extra-chromosomal DNA, are also present in many species of bacteria and archaea.

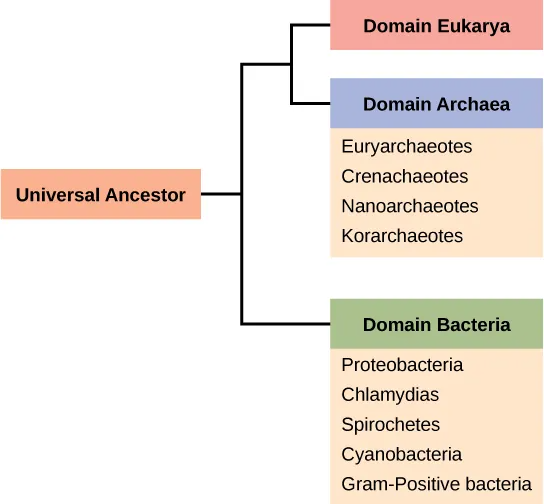

Recall that prokaryotes are divided into two different domains, Bacteria and Archaea, which together with Eukarya, comprise the three domains of life (Figure 22.11).

The Plasma Membrane of Prokaryotes

The prokaryotic plasma membrane is a thin lipid bilayer (6 to 8 nanometers) that completely surrounds the cell and separates the inside from the outside. Its selectively permeable nature keeps ions, proteins, and other molecules within the cell and prevents them from diffusing into the extracellular environment, while other molecules may move through the membrane. Recall that the general structure of a cell membrane is a phospholipid bilayer composed of two layers of lipid molecules.

The Cell Wall of Prokaryotes

The cytoplasm of prokaryotic cells has a high concentration of dissolved solutes. Therefore, the osmotic pressure within the cell is relatively high. The cell wall is a protective layer that surrounds some cells and gives them shape and rigidity. It is located outside the cell membrane and prevents osmotic lysis (bursting due to increasing volume). The chemical composition of the cell wall varies between Archaea and Bacteria, and also varies between bacterial species.

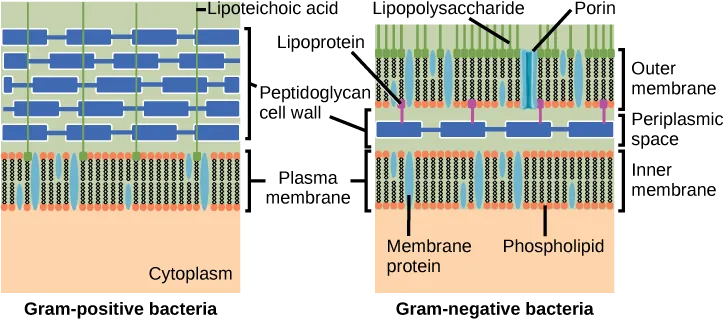

Bacterial cell walls contain peptidoglycan, composed of polysaccharide chains that are cross-linked by unusual peptides containing both L- and D-amino acids including D-glutamic acid and D-alanine. (Proteins normally have only L-amino acids; as a consequence, many of our antibiotics work by mimicking D-amino acids and therefore have specific effects on bacterial cell-wall development.) There are more than 100 different forms of peptidoglycan.

Bacteria are divided into two major groups: Gram positive and Gram negative, based on their reaction to Gram staining. Note that all Gram-positive bacteria belong to one phylum; bacteria in the other phyla (Proteobacteria, Chlamydias, Spirochetes, Cyanobacteria, and others) are Gram-negative. The Gram staining method is named after its inventor, Danish scientist Hans Christian Gram (1853–1938). The different bacterial responses to the staining procedure are ultimately due to cell wall structure. Gram-positive organisms typically lack the outer membrane found in Gram-negative organisms (Figure 22.16). Up to 90 percent of the cell-wall in Gram-positive bacteria is composed of peptidoglycan, and most of the rest is composed of acidic substances called teichoic acids. Teichoic acids may be covalently linked to lipids in the plasma membrane to form lipoteichoic acids. Lipoteichoic acids anchor the cell wall to the cell membrane. Gram-negative bacteria have a relatively thin cell wall composed of a few layers of peptidoglycan (only 10 percent of the total cell wall), surrounded by an outer envelope containing lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and lipoproteins. This outer envelope is sometimes referred to as a second lipid bilayer. The chemistry of this outer envelope is very different, however, from that of the typical lipid bilayer that forms plasma membranes.

Reproduction

Reproduction in prokaryotes is asexual and usually takes place by binary fission. (Recall that the DNA of a prokaryote is a single, circular chromosome.) Prokaryotes do not undergo mitosis; instead, the chromosome is replicated and the two resulting copies separate from one another, due to the growth of the cell. The prokaryote, now enlarged, is pinched inward at its equator and the two resulting cells, which are clones, separate. Binary fission does not provide an opportunity for genetic recombination or genetic diversity, but prokaryotes can share genes by three other mechanisms.

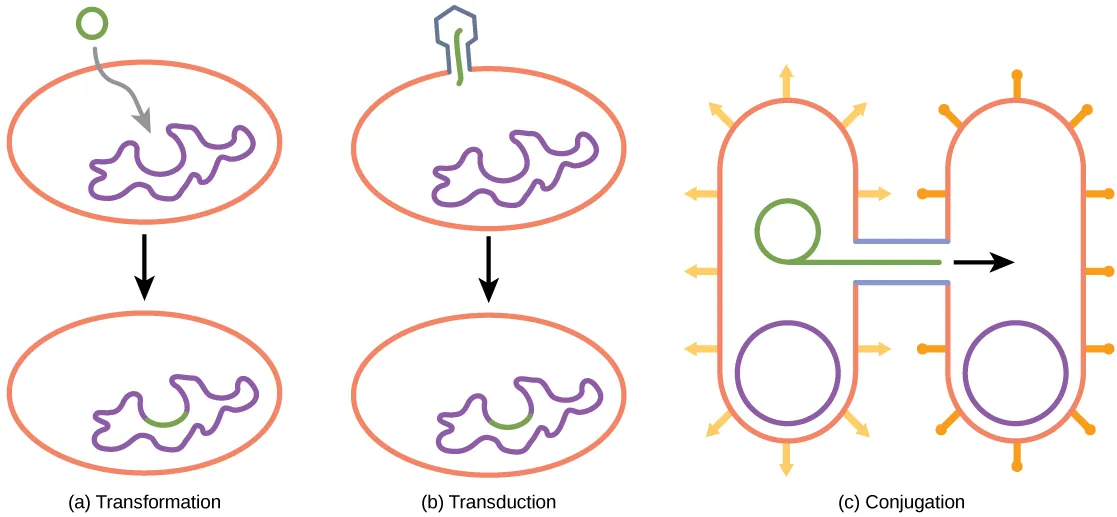

In transformation, the prokaryote takes in DNA shed by other prokaryotes into its environment. If a nonpathogenic bacterium takes up DNA for a toxin gene from a pathogen and incorporates the new DNA into its own chromosome, it too may become pathogenic.

In transduction, bacteriophages, the viruses that infect bacteria, may move short pieces of chromosomal DNA from one bacterium to another. Transduction results in a recombinant organism. Archaea also have viruses that may translocate genetic material from one individual to another.

In conjugation, DNA is transferred from one prokaryote to another by means of a pilus, which brings the organisms into contact with one another, and provides a channel for transfer of DNA. The DNA transferred can be in the form of a plasmid or as a composite molecule, containing both plasmid and chromosomal DNA.

These three processes of DNA exchange are shown in Figure 22.17.

Reproduction can be very rapid: a few minutes for some species. This short generation time coupled with mechanisms of genetic recombination and high rates of mutation result in the rapid evolution of prokaryotes, allowing them to respond to environmental changes (such as the introduction of an antibiotic) very quickly.

Link to Learning

Bacteria

This video summarizes some of the aspects of prokaryote form and function that you have read about. The video also explains how most bacteria are beneficial to us. Something important to realize as we move into the next section that talks about bacterial diseases.

central part of a prokaryotic cell in which the chromosome is found

rigid cell covering made of various molecules that protects the cell, provides structural support, and gives shape to the cell

external structure that enables a prokaryote to attach to surfaces and protects it from dehydration

material composed of polysaccharide chains cross-linked to unusual peptides

bacterium that contains mainly peptidoglycan in its cell walls

bacterium whose cell wall contains little peptidoglycan but has an outer membrane

process by which a prokaryote takes in DNA found in its environment that is shed by other prokaryotes

process by which a bacteriophage moves DNA from one prokaryote to another

process by which prokaryotes move DNA from one individual to another using a pilus