28.1 Phylum Porifera

Learning Outcomes

- Describe the organizational features of the simplest multicellular organisms such as sponges

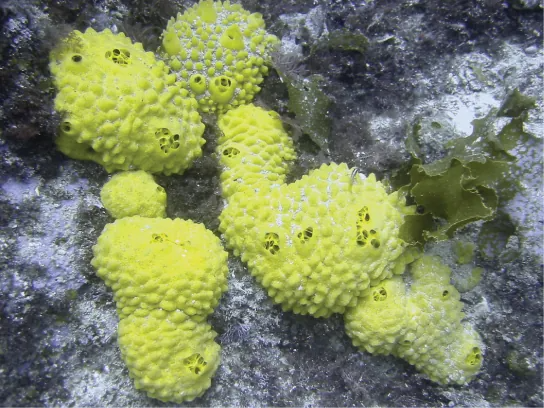

We will start our investigation with the simplest of all the invertebrates—animals sometimes classified within the clade Parazoa (“beside the animals”). This clade currently includes only the phylum Placozoa (containing a single species, Trichoplax adhaerens), and the phylum Porifera, containing the more familiar sponges (Figure 28.2). The split between the Parazoa and the Eumetazoa (all animal clades above Parazoa) likely took place over a billion years ago.

We should reiterate here that the Porifera do not possess “true” tissues that are embryologically homologous to those of all other derived animal groups such as the insects and mammals. This is because they do not create a true gastrula during embryogenesis, and as a result do not produce a true endoderm or ectoderm. But even though they are not considered to have true tissues, they do have specialized cells that perform specific functions like tissues (for example, the external “pinacoderm” of a sponge acts like our epidermis). Thus, functionally, the poriferans can be said to have tissues; however, these tissues are likely not embryologically homologous to our own.

Sponge larvae (e.g, parenchymula and amphiblastula) are flagellated and able to swim; however, adults are non-motile and spend their life attached to a substratum. Since water is vital to sponges for feeding, excretion, and gas exchange, their body structure facilitates the movement of water through the sponge. Various canals, chambers, and cavities enable water to move through the sponge to allow the exchange of food and waste as well as the exchange of gases to nearly all body cells.

Morphology of Sponges

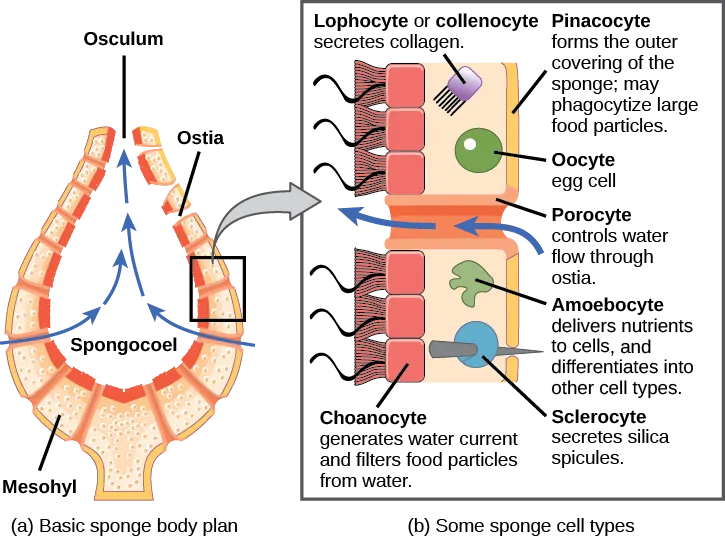

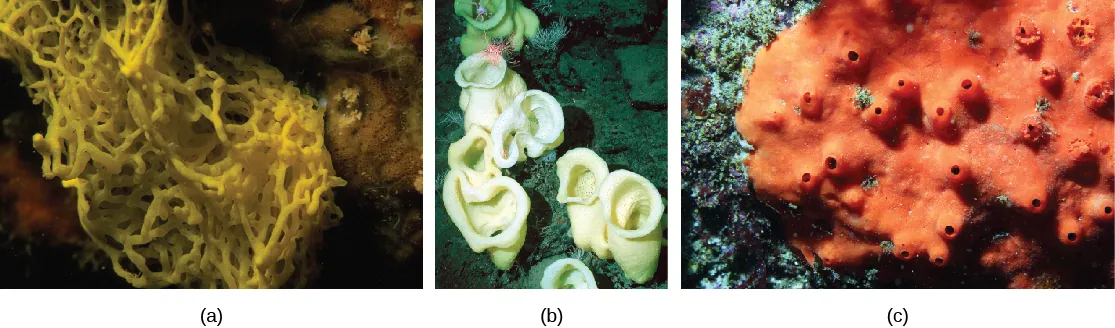

There are at least 5,000 named species of sponges, likely with thousands more yet to be classified. The morphology of the simplest sponges takes the shape of an irregular cylinder with a large central cavity, the spongocoel, occupying the inside of the cylinder (Figure 28.4). Water enters into the spongocoel through numerous pores, or ostia, that create openings in the body wall. Water entering the spongocoel is expelled via a large common opening called the osculum.

Link to Learning

Watch this video to see the movement of water through the sponge body.

Visual Connection

Physiological Process in Sponges

Sponges lack complex digestive, respiratory, circulatory, and nervous systems. Their food is trapped as water passes through the ostia and out through the osculum. In sponges, in spite of what looks like a large digestive cavity, all digestion is intracellular. The limit of this type of digestion is that food particles must be smaller than individual sponge cells.

All other major body functions in the sponge (gas exchange, circulation, excretion) are performed by diffusion between the cells that line the openings within the sponge and the water that is passing through those openings. All cell types within the sponge obtain oxygen from water through diffusion. Likewise, carbon dioxide is released into seawater by diffusion. In addition, nitrogenous waste produced as a byproduct of protein metabolism is excreted via diffusion by individual cells into the water as it passes through the sponge.

Although there is no specialized nervous system in sponges, there is intercellular communication that can regulate events like contraction of the sponge’s body or the activity of the choanocytes. Sponges reproduce by both sexual as well as asexual methods (e.g. budding or fragmentation).