29.4 Reptiles

Learning Objectives

- Describe the main characteristics of amniotes

- Identify the characteristics of reptiles

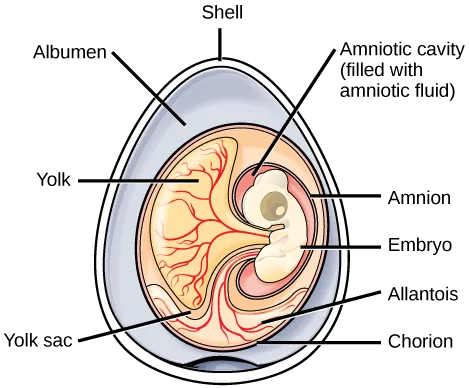

The reptiles (including dinosaurs and birds) are distinguished from amphibians by their terrestrially adapted egg, which is supported by four extraembryonic membranes: the yolk sac, the amnion, the chorion, and the allantois (Figure 29.22). The amnion forms a fluid-filled cavity that provides the embryo with is own internal aquatic environment. The evolution of the extraembryonic membranes led to less dependence on water for development and thus allowed the amniotes to branch out into drier environments.

In addition to these membranes, the eggs of birds, reptiles, and a few mammals have shells. An amniote embryo was then enclosed in the amnion, which was in turn encased in an extra-embryonic coelom contained within the chorion. Between the shell and the chorion was the albumin of the egg, which provided additional fluid and cushioning. This was a significant development that further distinguishes the amniotes from amphibians, which were and continue to be restricted to moist environments due their shell-less eggs. Although the shells of various reptilian amniotic species vary significantly, they all permit the retention of water and nutrients for the developing embryo. The egg shells of bird (avian reptiles) are hardened with calcium carbonate, making them rigid, but fragile. The shells of most nonavian reptile eggs, such as turtles, are leathery and require a moist environment.

Characteristics of Amniotes

The amniotic egg is the key characteristic of amniotes. In amniotes that lay eggs, the shell of the egg provides protection for the developing embryo while being permeable enough to allow for the exchange of carbon dioxide and oxygen. The albumin, or egg white, outside of the chorion provides the embryo with water and protein, whereas the fattier egg yolk contained in the yolk sac provides nutrients for the embryo, as is the case with the eggs of many other animals, such as amphibians.

Visual Connection

Additional derived characteristics of amniotes include a waterproof skin, accessory keratinized structures, and costal (rib) ventilation of the lungs.

Characteristics of Reptiles

Reptiles are tetrapods. Limbless reptiles—snakes and legless lizards—are classified as tetrapods because they are descended from four-limbed ancestors. Reptiles lay calcareous or leathery eggs enclosed in shells on land. Even aquatic reptiles return to the land to lay eggs. They reproduce sexually with internal fertilization.

One of the key adaptations that permitted reptiles to live on land was the development of their scaly skin, containing the protein keratin and waxy lipids, which reduced water loss from the skin. A number of keratinous epidermal structures have emerged in the descendants of various reptilian lineages and some have become defining characters for these lineages: scales, claws, nails, horns, feathers, and hair. Their occlusive skin means that reptiles cannot use their skin for respiration, like amphibians, and thus all amniotes breathe with lungs. All reptiles grow throughout their lives and regularly shed their skin, both to accommodate their growth and to rid themselves of ectoparasites. Snakes tend to shed the entire skin at one time, but other reptiles shed their skins in patches.

Most reptiles are ectotherms, animals whose main source of body heat comes from the environment; however, some crocodilians maintain elevated thoracic temperatures and thus appear to be at least regional endotherms. This is in contrast to true endotherms, which use heat produced by metabolism and muscle contraction to regulate body temperature over a very narrow temperature range, and thus are properly referred to as homeotherms. Reptiles have behavioral adaptations to help regulate body temperature, such as basking in sunny places to warm up through the absorption of solar radiation, or finding shady spots or going underground to minimize the absorption of solar radiation, which allows them to cool down and prevent overheating. The advantage of ectothermy is that metabolic energy from food is not required to heat the body; therefore, reptiles can survive on about 10 percent of the calories required by a similarly sized endotherm.

Class Reptilia includes many diverse species that are classified into four living clades:

1. Crocodilia: Alligators, crocodiles, gharials, and caimans

2. Sphenodontia: Tuataras

3. Squamata: Lizards and Snakes

4. Testudines: Turtles, terrapins, and tortoises