22.4 Bacterial Diseases and Antibiotics Resistance

Learning Outcomes

- Explain how the overuse of antibiotics may be creating “superbugs”

- Explain the importance of MRSA with respect to the problems of antibiotic resistance

To a prokaryote, humans may be just another housing opportunity. Unfortunately, the tenancy of some species can have harmful effects and cause disease. Bacteria or other infectious agents that cause harm to their human hosts are called pathogens. Devastating pathogen-borne diseases and plagues, both viral and bacterial in nature, have affected humans and their ancestors for millions of years. The true cause of these diseases was not understood until modern scientific thought developed; before this many people thought that diseases were a “spiritual punishment.” Only within the past several centuries have people understood that staying away from afflicted persons, disposing of the corpses and personal belongings of victims of illness, and sanitation practices reduced their own chances of getting sick.

Epidemiologists study how diseases are transmitted and how they affect a population. Often, they are following the course of an epidemic—a disease that occurs in an unusually high number of individuals in a population at the same time. In contrast, a pandemic is a widespread, and usually worldwide, epidemic. An endemic disease is a disease that is always present, usually at low incidence, in a population.

Antibiotics: Are We Facing a Crisis?

The word antibiotic comes from the Greek anti meaning “against” and bios meaning “life.” An antibiotic is a chemical, produced either by microbes or synthetically, that is hostile to or prevents the growth of other organisms. Today’s media often address concerns about an antibiotic crisis. Are the antibiotics that easily treated bacterial infections in the past becoming obsolete? Are there new “superbugs”—bacteria that have evolved to become more resistant to our arsenal of antibiotics? Is this the beginning of the end of antibiotics? All these questions challenge the healthcare community.

One of the main causes of antibiotic resistance in bacteria is overexposure to antibiotics. The imprudent and excessive use of antibiotics has resulted in the natural selection of resistant forms of bacteria. The antibiotic kills most of the infecting bacteria, and therefore only the resistant forms remain. These resistant forms reproduce, resulting in an increase in the proportion of resistant forms over non-resistant ones. In addition to transmission of resistance genes to progeny, lateral transfer of resistance genes on plasmids can rapidly spread these genes through a bacterial population. A major misuse of antibiotics is in patients with viral infections like colds or the flu, against which antibiotics are useless. Another problem is the excessive use of antibiotics in livestock. The routine use of antibiotics in animal feed promotes bacterial resistance as well. In the United States, 70 percent of the antibiotics produced are fed to animals. These antibiotics are given to livestock in low doses, which maximize the probability of resistance developing, and these resistant bacteria are readily transferred to humans.

One of the Superbugs: MRSA

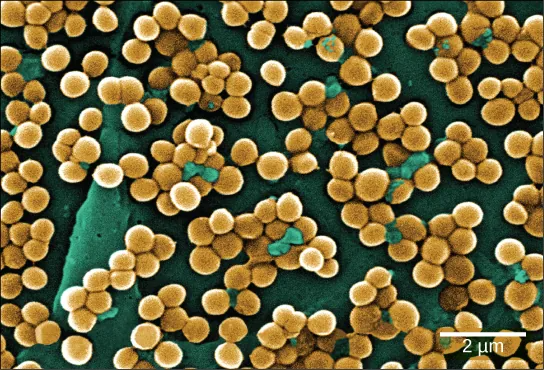

The imprudent use of antibiotics has paved the way for the expansion of resistant bacterial populations. For example, Staphylococcus aureus, often called “staph,” is a common bacterium that can live in the human body and is usually easily treated with antibiotics. However, a very dangerous strain, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) has made the news over the past few years (Figure 22.25). This strain is resistant to many commonly used antibiotics, including methicillin, amoxicillin, penicillin, and oxacillin. MRSA can cause infections of the skin, but it can also infect the bloodstream, lungs, urinary tract, or sites of injury. While MRSA infections are common among people in healthcare facilities, they have also appeared in healthy people who haven’t been hospitalized, but who live or work in tight populations (like military personnel and prisoners). Researchers have expressed concern about the way this latter source of MRSA targets a much younger population than those residing in care facilities. The Journal of the American Medical Association reported that, among MRSA-afflicted persons in healthcare facilities, the average age is 68, whereas people with “community-associated MRSA” (CA-MRSA) have an average age of 23.4

Link to Learning

What causes antibiotic resistance?

Right now, you are inhabited by trillions of microorganisms. Many of these bacteria are harmless (or even helpful!), but there are a few strains of ‘super bacteria’ that are pretty nasty — and they’re growing resistant to our antibiotics. Why is this happening? This Ted Ed video details the evolution of this problem that presents a big challenge for the future of medicine.

In summary, the medical community is facing an antibiotic crisis. Some scientists believe that after years of being protected from bacterial infections by antibiotics, we may be returning to a time in which a simple bacterial infection could again devastate the human population. Researchers are developing new antibiotics, but it takes many years of research and clinical trials, plus financial investments in the millions of dollars, to generate an effective and approved drug.

disease that occurs in an unusually high number of individuals in a population at the same time

widespread, usually worldwide, epidemic disease

disease that is constantly present, usually at low incidence, in a population

biological substance that, in low concentration, is antagonistic to the growth of prokaryotes