27.2 Features Used to Classify Animals

Learning Outcomes

- Explain the differences in animal body plans that support basic animal classification

- Compare and contrast the embryonic development of protostomes and deuterostomes

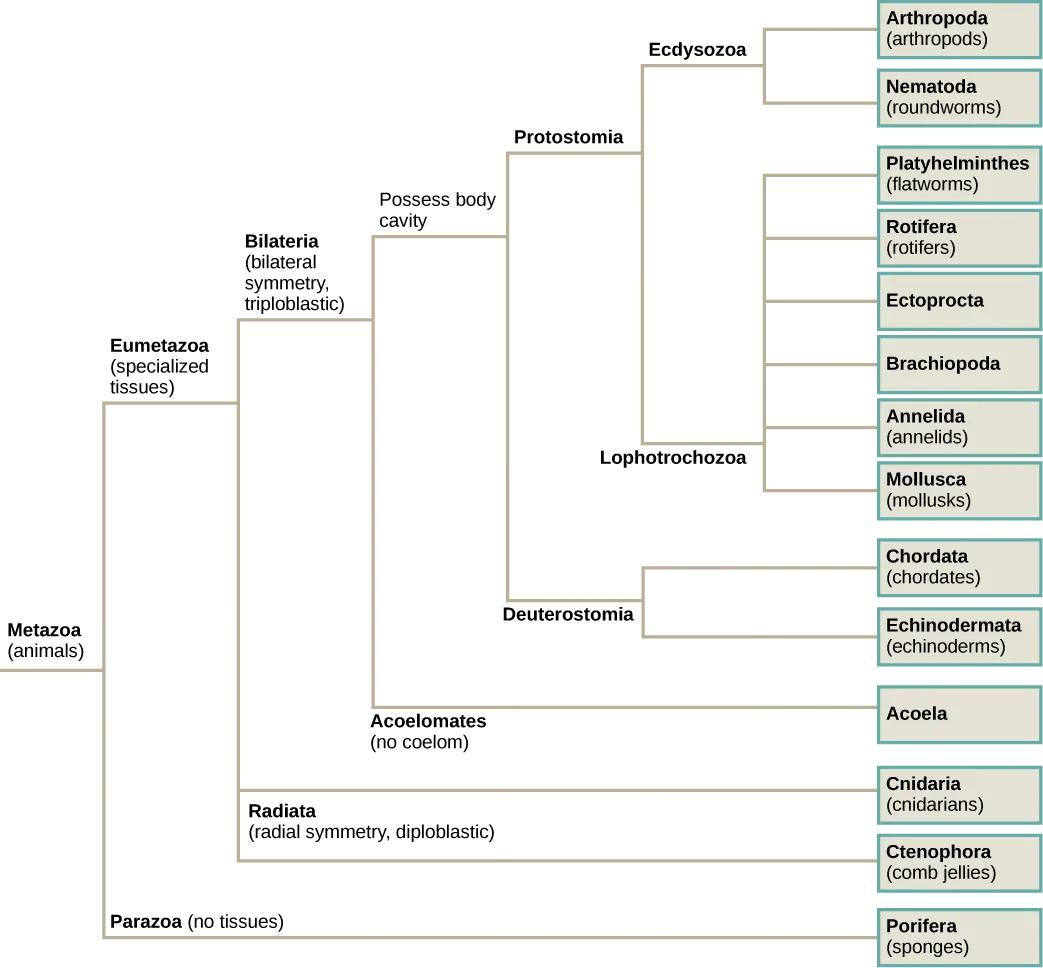

Scientists have developed a classification scheme that categorizes all members of the animal kingdom, although there are exceptions to most “rules” governing animal classification (Figure 27.6). Animals have been traditionally classified according to two characteristics: body plan and developmental pathway. The major feature of the body plan is its symmetry: how the body parts are distributed along the major body axis. Symmetrical animals can be divided into roughly equivalent halves along at least one axis. Developmental characteristics include the number of germ tissue layers formed during development, the origin of the mouth and anus, the presence or absence of an internal body cavity, and other features of embryological development, such as larval types or whether or not periods of growth are interspersed with molting.

Visual Connection

Animal Characterization Based on Body Symmetry

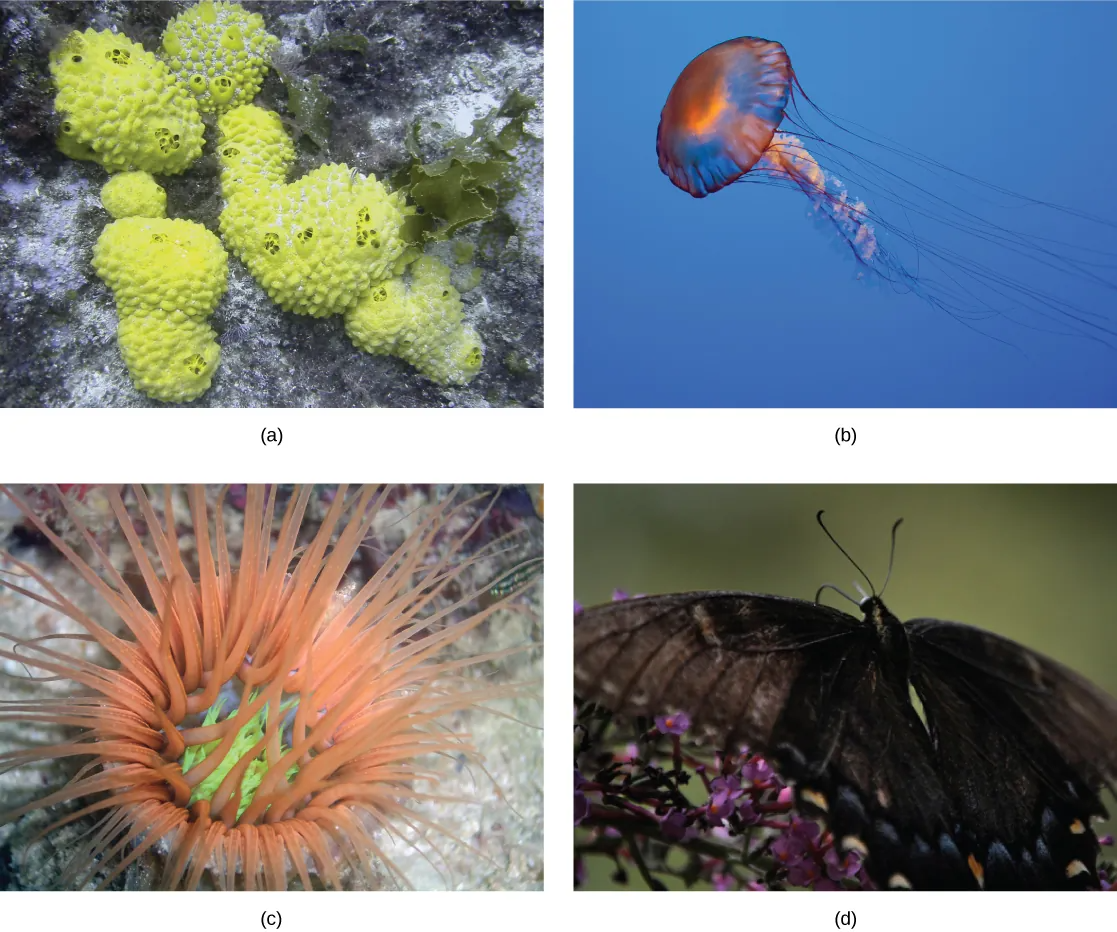

At a very basic level of classification, true animals can be largely divided into three groups based on the type of symmetry of their body plan: radially symmetrical, bilaterally symmetrical, and asymmetrical. Asymmetry is seen in two modern clades, the Parazoa (Figure 27.7a) and Placozoa. (Although we should note that the ancestral fossils of the Parazoa apparently exhibited bilateral symmetry.) One clade, the Cnidaria (Figure 27.7b,c), exhibits radial or biradial symmetry: Ctenophores have rotational symmetry (Figure 27.7e). Bilateral symmetry is seen in the largest of the clades, the Bilateria (Figure 27.7d); however the Echinodermata are bilateral as larvae and metamorphose secondarily into radial adults. All types of symmetry are well suited to meet the unique demands of a particular animal’s lifestyle.

Radial symmetry is the arrangement of body parts around a central axis, as is seen in a bicycle wheel or pie. It results in animals having top and bottom surfaces but no left and right sides, nor front or back. If a radially symmetrical animal is divided in any direction along the oral/aboral axis (the side with a mouth is “oral side,” and the side without a mouth is the “aboral side”), the two halves will be mirror images. This form of symmetry marks the body plans of many animals in the phyla Cnidaria, including jellyfish and adult sea anemones (Figure 27.7b, c). Radial symmetry equips these sea creatures (which may be sedentary or only capable of slow movement or floating) to experience the environment equally from all directions. Bilaterally symmetrical animals, like butterflies (Figure 27.7d) have only a single plane along which the body can be divided into equivalent halves.

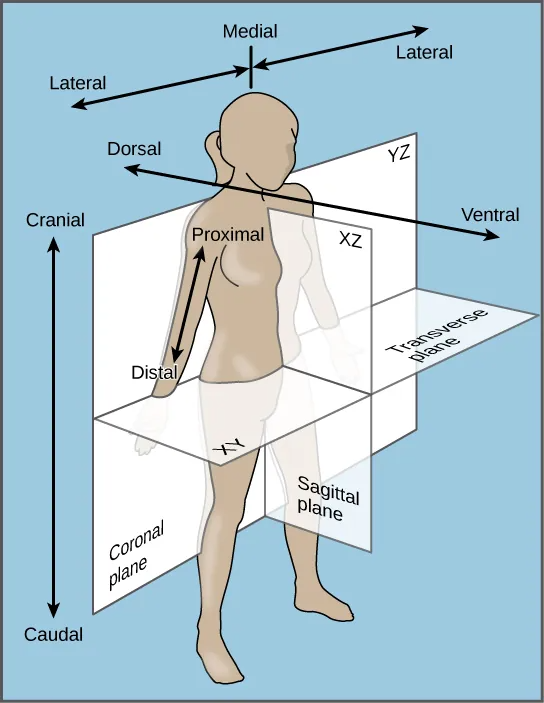

Bilateral symmetry involves the division of the animal through a midsagittal plane, resulting in two superficially mirror images, right and left halves, such as those of a butterfly (Figure 27.7d), crab, or human body. Animals with bilateral symmetry have a “head” and “tail” (anterior vs. posterior), front and back (dorsal vs. ventral), and right and left sides (Figure 27.8). All Eumetazoa except those with secondary radial symmetry are bilaterally symmetrical. The evolution of bilateral symmetry that allowed for the formation of anterior and posterior (head and tail) ends promoted a phenomenon called cephalization, which refers to the collection of an organized nervous system at the animal’s anterior end. In contrast to radial symmetry, which is best suited for stationary or limited-motion lifestyles, bilateral symmetry allows for streamlined and directional motion. In evolutionary terms, this simple form of symmetry promoted active and controlled directional mobility and increased sophistication of resource-seeking and predator-prey relationships.

Link to Learning

Watch this video to see a quick sketch of the different types of body symmetry.

Animal Characterization Based on Features of Embryological Development

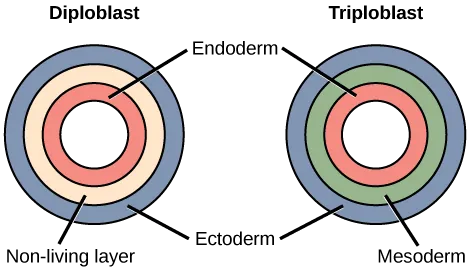

Most animal species undergo a separation of tissues into germ layers during embryonic development. Animals develop either two or three embryonic germ layers (Figure 27.9). The animals that display radial, biradial, or rotational symmetry develop two germ layers, an inner layer (endoderm) and an outer layer (ectoderm). These animals are called diploblasts, and have a nonliving middle layer between the endoderm and ectoderm (although individual cells may be distributed through this middle layer, there is no coherent third layer of tissue). The four clades considered to be diploblastic have different levels of complexity and different developmental pathways, although there is little information about development in Placozoa. More complex animals (usually those with bilateral symmetry) develop three tissue layers: an inner layer (endoderm), an outer layer (ectoderm), and a middle layer (mesoderm). Animals with three tissue layers are called triploblasts.

Visual Connection

Each of the three germ layers is programmed to give rise to specific body tissues and organs, although there are variations on these themes. Generally speaking, the endoderm gives rise to the lining of the digestive tract (including the stomach, intestines, liver, and pancreas), as well as to the lining of the trachea, bronchi, and lungs of the respiratory tract, along with a few other structures. The ectoderm develops into the outer epithelial covering of the body surface, the central nervous system, and a few other structures. The mesoderm is the third germ layer; it forms between the endoderm and ectoderm in triploblasts. This germ layer gives rise to all specialized muscle tissues (including the cardiac tissues and muscles of the intestines), connective tissues such as the skeleton and blood cells, and most other visceral organs such as the kidneys and the spleen. Diploblastic animals may have cell types that serve multiple functions, such as epitheliomuscular cells, which serve as a covering as well as contractile cells.

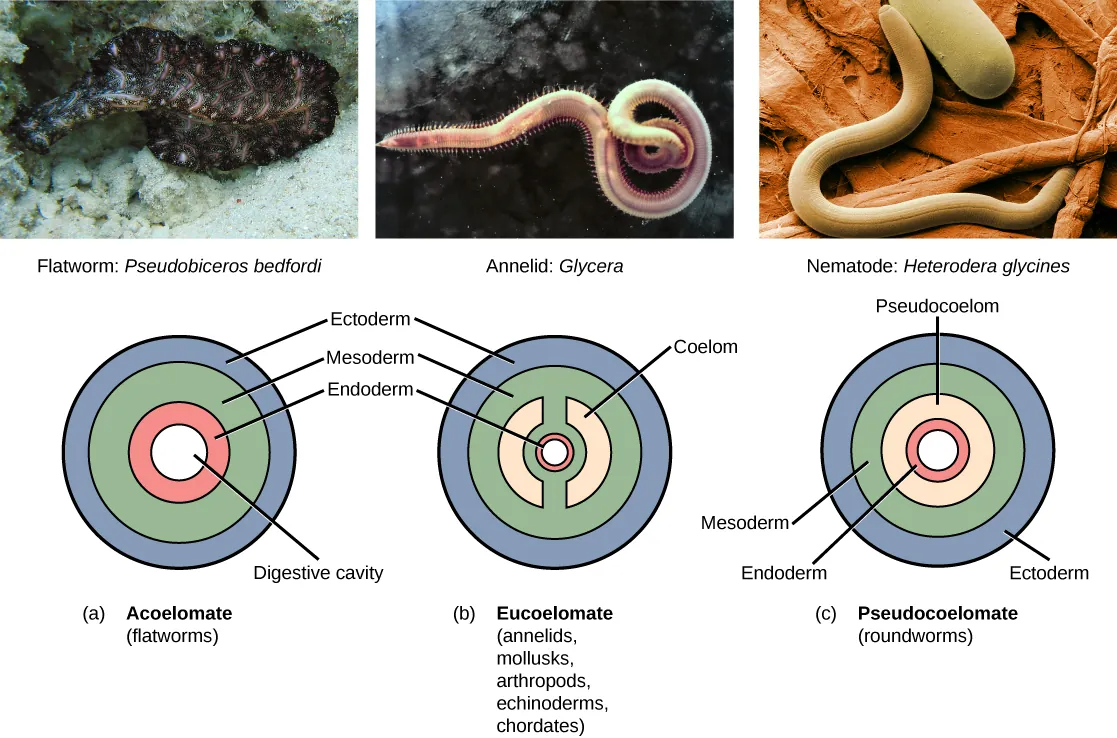

Presence or Absence of a Coelom

Further subdivision of animals with three germ layers (triploblasts) results in the separation of animals that may develop an internal body cavity derived from mesoderm, called a coelom, and those that do not. This epithelial cell-lined coelomic cavity, usually filled with fluid, lies between the visceral organs and the body wall. It houses many organs such as the digestive, urinary, and reproductive systems, the heart and lungs, and also contains the major arteries and veins of the circulatory system. In mammals, the body cavity is divided into the thoracic cavity, which houses the heart and lungs, and the abdominal cavity, which houses the digestive organs. In the thoracic cavity further subdivision produces the pleural cavity, which provides space for the lungs to expand during breathing, and the pericardial cavity, which provides room for movements of the heart. The evolution of the coelom is associated with many functional advantages. For example, the coelom provides cushioning and shock absorption for the major organ systems that it encloses. In addition, organs housed within the coelom can grow and move freely, which promotes optimal organ development and placement. The coelom also provides space for the diffusion of gases and nutrients, as well as body flexibility, promoting improved animal motility.

Triploblasts that do not develop a coelom are called acoelomates, and their mesoderm region is completely filled with tissue, although they do still have a gut cavity. Examples of acoelomates include animals in the phylum Platyhelminthes, also known as flatworms. Animals with a true coelom are called eucoelomates (or coelomates) (Figure 27.10). In such cases, a true coelom arises entirely within the mesoderm germ layer and is lined by an epithelial membrane. This membrane also lines the organs within the coelom, connecting and holding them in position while allowing them some freedom of movement. Annelids, mollusks, arthropods, echinoderms, and chordates are all eucoelomates. A third group of triploblasts has a slightly different coelom lined partly by mesoderm and partly by endoderm. Although still functionally a coelom, these are considered “false” coeloms, and so we call these animals pseudocoelomates. The phylum Nematoda (roundworms) is an example of a pseudocoelomate. True coelomates can be further characterized based on other features of their early embryological development.

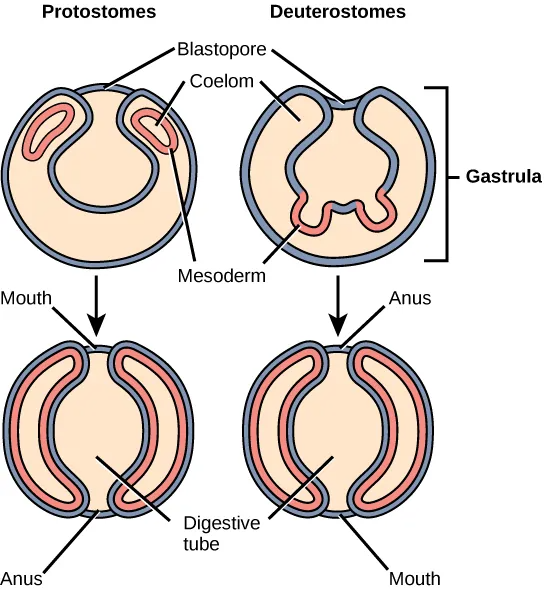

Embryonic Development of the Mouth

Bilaterally symmetrical, tribloblastic eucoelomates can be further divided into two groups based on differences in the origin of the mouth. When the primitive gut forms, the opening that first connects the gut cavity to the outside of the embryo is called the blastopore. Most animals have openings at both ends of the gut: mouth at one end and anus at the other. One of these openings will develop at or near the site of the blastopore. In Protostomes (“mouth first”), the mouth develops at the blastopore (Figure 27.11). In Deuterostomes (“mouth second”), the mouth develops at the other end of the gut (Figure 27.11) and the anus develops at the site of the blastopore. Protostomes include arthropods, mollusks, and annelids. Deuterostomes include more complex animals such as chordates but also some “simple” animals such as echinoderms. Recent evidence has challenged this simple view of the relationship between the location of the blastopore and the formation of the mouth, however, and the theory remains under debate. Nevertheless, these details of mouth and anus formation reflect general differences in the organization of protostome and deuterostome embryos, which are also expressed in other developmental features.

Link to Learning

Watch this Crash Course Biology Video: “We’re Just Tubes.”

Activity

Now practice your knowledge of Animal Body Terms with this Materia Widget!