32.2 Pollination and Fertilization

Learning Outcomes

- Describe what must occur for plant fertilization

- Explain cross-pollination and the ways in which it takes place

- Describe the process that leads to the development of a seed

- Define double fertilization

In angiosperms, pollination is defined as the placement or transfer of pollen from the anther to the stigma of the same flower or another flower. In gymnosperms, pollination involves pollen transfer from the male cone to the female cone. Upon transfer, the pollen germinates to form the pollen tube and the sperm for fertilizing the egg.

Pollination takes two forms: self-pollination and cross-pollination. Self-pollination occurs when the pollen from the anther is deposited on the stigma of the same flower, or another flower on the same plant. Cross-pollination is the transfer of pollen from the anther of one flower to the stigma of another flower on a different plant of the same species. Self-pollination occurs in flowers where the stamen and carpel mature at the same time, and are positioned so that the pollen can land on the flower’s stigma. This method of pollination does not require an investment from the plant to provide nectar and pollen as food for pollinators.

Link to Learning

Cross vs. Self Pollination

Explore this interactive website to review self-pollination and cross-pollination.

Living species are designed to ensure survival of their progeny; those that fail become extinct. Genetic diversity is therefore required so that in a changing environment some of the progeny can survive. Self-pollination leads to the production of plants with less genetic diversity, since genetic material from the same plant is used to form gametes, and eventually, the zygote. In contrast, cross-pollination leads to greater genetic diversity because the microgametophyte and megagametophyte are derived from different plants.

Because cross-pollination allows for more genetic diversity, plants have developed many ways to avoid self-pollination. In some species, the pollen and the ovary mature at different times. By the time pollen matures and has been shed, the stigma of this flower is mature and can only be pollinated by pollen from another flower. Some flowers have developed physical features that prevent self-pollination. Many plants have male and female flowers located on different parts of the plant, thus making self-pollination difficult. In yet other species, the male and female flowers are borne on different plants (dioecious). All of these are barriers to self-pollination; therefore, the plants depend on pollinators to transfer pollen. The majority of pollinators are biotic agents such as insects, bats, birds, and other animals. Other plant species are pollinated by abiotic agents, such as wind and water.

Pollination by Insects

Bees are perhaps the most important pollinator of many garden plants and most commercial fruit trees (Figure 32.12). The most common species of bees are bumblebees and honeybees. Bees collect energy-rich pollen or nectar for their survival and energy needs. They visit flowers that are open during the day, are brightly colored, have a strong scent, and have a tubular shape, typically with the presence of a nectar guide. A nectar guide includes regions on the flower petals that are visible only to bees; it helps to guide bees to the center of the flower, thus making the pollination process more efficient. The pollen sticks to the bees’ fuzzy hair, and when the bee visits another flower, some of the pollen is transferred to the second flower. Recently, there have been many reports about the declining population of honeybees. Many flowers will remain unpollinated and not bear seed if honeybees disappear. The impact on commercial fruit growers could be devastating.

Many flies are attracted to flowers that have a decaying smell or an odor of rotting flesh. These flowers, which produce nectar, usually have dull colors, such as brown or purple. The nectar provides energy, whereas the pollen provides protein. Wasps are also important insect pollinators, and pollinate many species of figs.

Butterflies, such as the monarch, pollinate many garden flowers and wildflowers. These flowers are brightly colored, have a strong fragrance, are open during the day, and have nectar guides to make access to nectar easier. The pollen is picked up and carried on the butterfly’s limbs. Moths, on the other hand, pollinate flowers during the late afternoon and night. The flowers pollinated by moths are pale or white and are flat, enabling the moths to land.

Pollination by Bats

In the tropics and deserts, bats are often the pollinators of nocturnal flowers such as agave, guava, and morning glory. The flowers are usually large and white or pale-colored; thus, they can be distinguished from the dark surroundings at night. The flowers have a strong, fruity, or musky fragrance and produce large amounts of nectar. They are naturally large and wide-mouthed to accommodate the head of the bat. As the bats seek the nectar, their faces and heads become covered with pollen, which is then transferred to the next flower.

Pollination by Birds

Many species of small birds, such as the hummingbird (Figure 32.14) are pollinators for plants such as orchids and other wildflowers. Flowers visited by birds are usually sturdy and are oriented in such a way as to allow the birds to stay near the flower without getting their wings entangled in the nearby flowers. The flower typically has a curved, tubular shape, which allows access for the bird’s beak. Brightly colored, odorless flowers that are open during the day are pollinated by birds. As a bird seeks energy-rich nectar, pollen is deposited on the bird’s head and neck and is then transferred to the next flower it visits.

Pollination by Wind

Most species of conifers, and many angiosperms, such as grasses, maples and oaks, are pollinated by wind. Pine cones are brown and unscented, while the flowers of wind-pollinated angiosperm species are usually green, small, may have small or no petals, and produce large amounts of pollen. Unlike the typical insect-pollinated flowers, flowers adapted to pollination by wind do not produce nectar or scent. In wind-pollinated species, the microsporangia hang out of the flower, and, as the wind blows, the lightweight pollen is carried with it (Figure 32.15).

Evolution Connection

Pollination by Deception

Orchids are highly valued flowers, with many rare varieties (Figure 32.17). They grow in a range of specific habitats, mainly in the tropics of Asia, South America, and Central America. At least 25,000 species of orchids have been identified.

Flowers often attract pollinators with food rewards, in the form of nectar. However, some species of orchid are an exception to this standard: they have evolved different ways to attract the desired pollinators. They use a method known as food deception, in which bright colors and perfumes are offered, but no food. Anacamptis morio, commonly known as the green-winged orchid, bears bright purple flowers and emits a strong scent. The bumblebee, its main pollinator, is attracted to the flower because of the strong scent—which usually indicates food for a bee—and in the process, picks up the pollen to be transported to another flower.

Other orchids use sexual deception. Chiloglottis trapeziformis emits a compound that smells the same as the pheromone emitted by a female wasp to attract male wasps. The male wasp is attracted to the scent, lands on the orchid flower, and in the process, transfers pollen. Some orchids, like the Australian hammer orchid, use scent as well as visual trickery in yet another sexual deception strategy to attract wasps. The flower of this orchid mimics the appearance of a female wasp and emits a pheromone. The male wasp tries to mate with what appears to be a female wasp, and in the process, picks up pollen, which it then transfers to the next counterfeit mate.

Double Fertilization

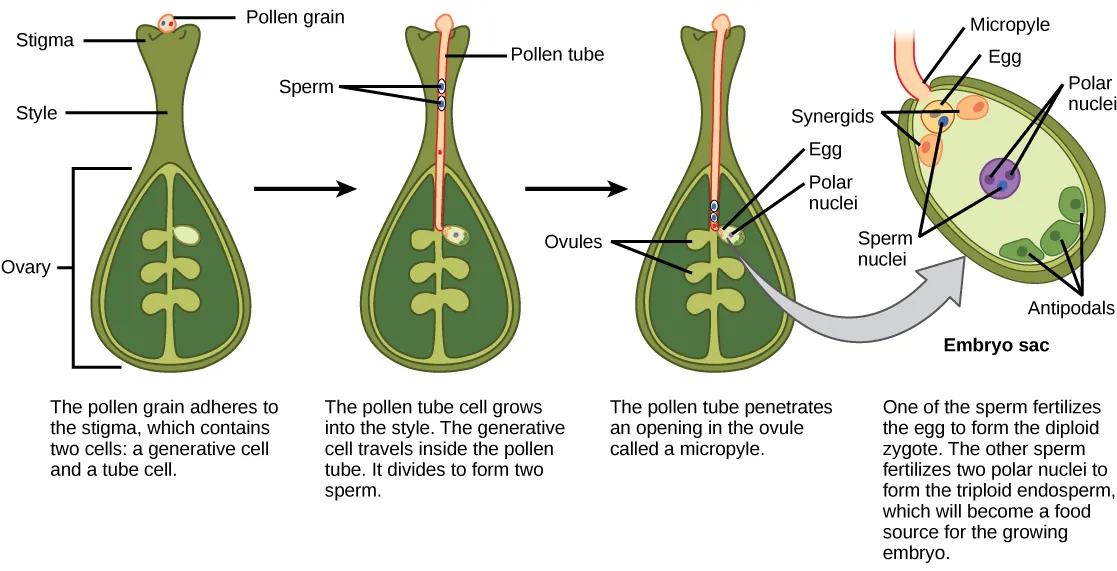

After pollen is deposited on the stigma, it must germinate and grow through the style to reach the ovule. The pollen, contain two cells: the pollen tube cell and the generative cell. The pollen tube cell grows into a pollen tube through which the generative cell travels. If the generative cell has not already split into two cells, it now divides to form two sperm cells. Of the two sperm cells, one sperm fertilizes the egg cell, forming a diploid zygote; the other sperm fuses with the two polar nuclei, forming a triploid cell that develops into the endosperm. Together, these two fertilization events in angiosperms are known as double fertilization (Figure 32.18). After fertilization is complete, no other sperm can enter. The fertilized ovule forms the seed, whereas the tissues of the ovary become the fruit, usually enveloping the seed.

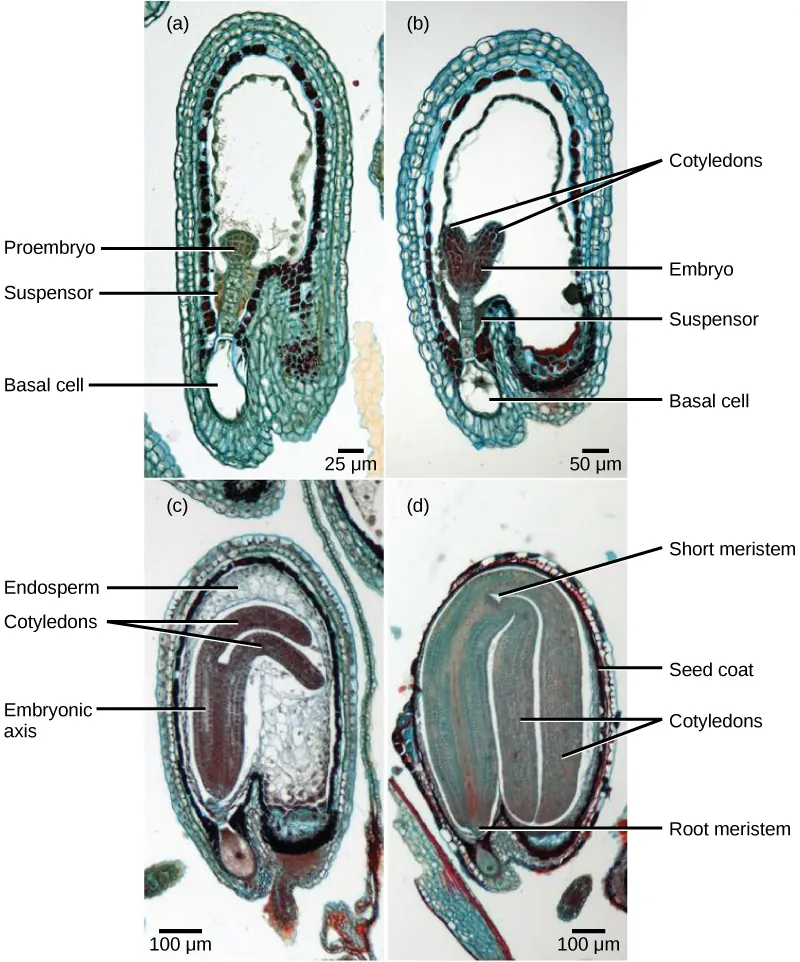

After fertilization, the zygote divides via mitosis. In dicots (eudicots), the developing embryo has a heart shape, due to the presence of the two rudimentary cotyledons (Figure 32.19b). As the embryo and cotyledons enlarge, they run out of room inside the developing seed, and are forced to bend (Figure 32.19c). Ultimately, the embryo and cotyledons fill the seed (Figure 32.19d), and the seed is ready for dispersal. Embryonic development is suspended after some time, and growth is resumed only when the seed germinates. The developing seedling will rely on the food reserves stored in the cotyledons until the first set of leaves begin photosynthesis.

Development of the Seed

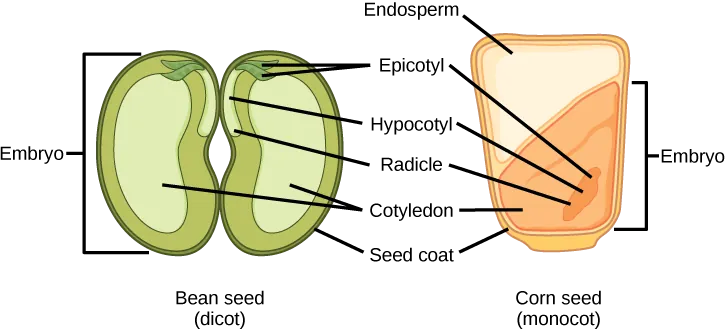

The mature ovule develops into the seed. A typical seed contains a seed coat, cotyledons, endosperm, and a single embryo (Figure 32.20).

Visual Connection

Monocot vs. Dicot Seed

The storage of food reserves in angiosperm seeds differs between monocots and dicots. In monocots, such as corn and wheat, the single cotyledon is connected by vascular tissue to the endosperm where food reserves are stored . Upon germination, enzymes degrade the stored carbohydrates, proteins and lipids, to sustain the seedling until the first leaves are formed.

The two cotyledons in the dicot seed also have vascular connections to the embryo. In endospermic dicots, the food reserves are stored in the endosperm. During germination, the two cotyledons therefore act as absorptive organs to absorb the released food reserves in the endosperm. The seed, along with the ovule, is protected by a seed coat that is formed from the integuments of the ovule sac.

Seed Germination

Many mature seeds enter a period of inactivity, known as dormancy, which may last for months, years, or even centuries. Dormancy helps keep seeds viable during unfavorable conditions. Upon a return to favorable conditions, seed germination takes place. Favorable conditions could be as diverse as moisture, light, cold, fire, or chemical treatments. After heavy rains, many new seedlings emerge. Forest fires also lead to the emergence of new seedlings. Some seeds require vernalization (cold treatment) before they can germinate. This guarantees that seeds produced by plants in temperate climates will not germinate until the spring.

Depending on seed size, the time taken for a seedling to emerge may vary. Species with large seeds have enough food reserves to germinate deep below ground. Seeds of small-seeded species usually require light as a germination cue. This ensures the seeds only germinate at or near the soil surface (where the light is greatest). If they were to germinate too far underneath the surface, the developing seedling would not have enough food reserves to reach the sunlight.

Development of Fruit and Fruit Types

After fertilization, the ovary of the flower usually develops into the fruit. Fruits are usually associated with having a sweet taste; however, not all fruits are sweet. Some fruits develop from the ovary and are known as true fruits, whereas others develop from other parts of the female gametophyte and are known as accessory fruits. The fruit encloses the seeds and the developing embryo, thereby providing it with protection. As the fruit matures, the seeds also mature.

Fruits generally have three parts: the exocarp (the outermost skin or covering), the mesocarp (middle part of the fruit), and the endocarp (the inner part of the fruit). Together, all three are known as the pericarp. The mesocarp is usually the fleshy, edible part of the fruit. In many fruits, two or all three of the layers are fused, and are indistinguishable at maturity. Fruits can be dry (nuts) or fleshy.

Fruit and Seed Dispersal

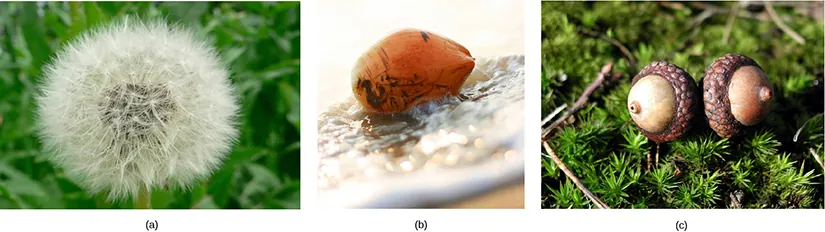

The fruit has a single purpose: seed dispersal. Seeds contained within fruits need to be dispersed far from the mother plant, so they may less competitive conditions in which to germinate and grow.

Some fruit have built-in mechanisms so they can disperse by themselves, whereas others require the help of agents like wind, water, and animals (Figure 32.23). Wind-dispersed fruit are lightweight and may have wing-like appendages that allow them to be carried by the wind.

Seeds dispersed by water are contained in light and buoyant fruit, giving them the ability to float. Coconuts are well known for their ability to float on water to reach land where they can germinate.

Animals and birds eat fruits, and the seeds that are not digested are excreted in their droppings some distance away. Some animals, like squirrels, bury seed-containing fruits for later use; if the squirrel does not find its stash, and if conditions are favorable, the seeds germinate.

All of the above mechanisms allow for seeds to be dispersed through space, much like an animal’s offspring can move to a new location. Seed dormancy, which was described earlier, allows plants to disperse their progeny through time: something animals cannot do. Dormant seeds can wait months, years, or even decades for the proper conditions for germination and propagation of the species.