Chapter 9: Political Parties

What Are Parties and How Did They Form?

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe political parties and what they do

- Differentiate political parties from interest groups

- Explain how U.S. political parties formed

At some point, most of us have found ourselves part of a group trying to solve a problem, like picking a restaurant or movie to attend, or completing a big project at school or work. Members of the group probably had various opinions about what should be done. Some may have even refused to help make the decision or to follow it once it had been made. Still others may have been willing to follow along but were less interested in contributing to a workable solution. Because of this disagreement, at some point, someone in the group had to find a way to make a decision, negotiate a compromise, and ultimately do the work needed for the group to accomplish its goals.

This kind of collective action problem is very common in societies, as groups and entire societies try to solve problems or distribute scarce resources. In modern U.S. politics, such problems are usually solved by two important types of organizations: interest groups and political parties. There are many interest groups, all with opinions about what should be done and a desire to influence policy. Because they are usually not officially affiliated with any political party, they generally have no trouble working with either of the major parties. But at some point, a society must find a way of taking all these opinions and turning them into solutions to real problems. That is where political parties come in. Essentially, political parties are groups of people with similar interests who work together to create and implement policies. They do this by gaining control over the government by winning elections. Party platforms guide members of Congress in drafting legislation. Parties guide proposed laws through Congress and inform party members how they should vote on important issues. Political parties also nominate candidates to run for state government, Congress, and the presidency. Finally, they coordinate political campaigns and mobilize voters.

POLITICAL PARTIES AS UNIQUE ORGANIZATIONS

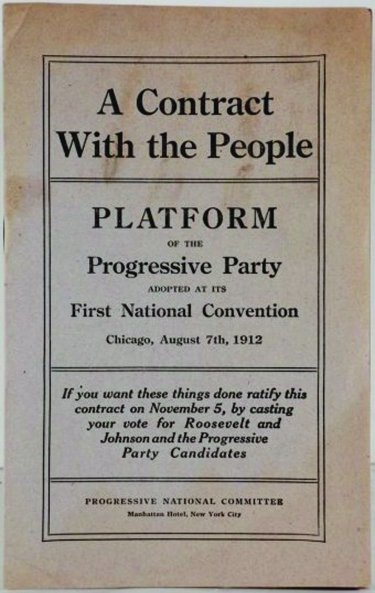

In Federalist No. 10, written in the late eighteenth century, James Madison noted that the formation of self-interested groups, which he called factions, was inevitable in any society, as individuals started to work together to protect themselves from the government. Interest groups and political parties are two of the most easily identified forms of factions in the United States. These groups are similar in that they are both mediating institutions responsible for communicating public preferences to the government. They are not themselves government institutions in a formal sense. Neither is directly mentioned in the U.S. Constitution nor do they have any real, legal authority to influence policy. But whereas interest groups often work indirectly to influence our leaders, political parties are organizations that try to directly influence public policy through its members who seek to win and hold public office. Parties accomplish this by identifying and aligning sets of issues that are important to voters in the hopes of gaining support during elections; their positions on these critical issues are often presented in documents known as a party platform ((Figure)), which is adopted at each party’s presidential nominating convention every four years. If successful, a party can create a large enough electoral coalition to gain control of the government. Once in power, the party is then able to deliver, to its voters and elites, the policy preferences they choose by electing its partisans to the government. In this respect, parties provide choices to the electorate, something they are doing that is in such sharp contrast to their opposition.

Winning elections and implementing policy would be hard enough in simple political systems, but in a country as complex as the United States, political parties must take on great responsibilities to win elections and coordinate behavior across the many local, state, and national governing bodies. Indeed, political differences between states and local areas can contribute much complexity. If a party stakes out issue positions on which few people agree and therefore builds too narrow a coalition of voter support, that party may find itself marginalized. But if the party takes too broad a position on issues, it might find itself in a situation where the members of the party disagree with one another, making it difficult to pass legislation, even if the party can secure victory.

It should come as no surprise that the story of U.S. political parties largely mirrors the story of the United States itself. The United States has seen sweeping changes to its size, its relative power, and its social and demographic composition. These changes have been mirrored by the political parties as they have sought to shift their coalitions to establish and maintain power across the nation and as party leadership has changed. As you will learn later, this also means that the structure and behavior of modern parties largely parallel the social, demographic, and geographic divisions within the United States today. To understand how this has happened, we look at the origins of the U.S. party system.

HOW POLITICAL PARTIES FORMED

National political parties as we understand them today did not really exist in the United States during the early years of the republic. Most politics during the time of the nation’s founding were local in nature and based on elite politics, limited suffrage (or the ability to vote in elections), and property ownership. Residents of the various colonies, and later of the various states, were far more interested in events in their state legislatures than in those occurring at the national level or later in the nation’s capital. To the extent that national issues did exist, they were largely limited to collective security efforts to deal with external rivals, such as the British or the French, and with perceived internal threats, such as conflicts with Native Americans.

Soon after the United States emerged from the Revolutionary War, however, a rift began to emerge between two groups that had very different views about the future direction of U.S. politics. Thus, from the very beginning of its history, the United States has had a system of government dominated by two different philosophies. Federalists, who were largely responsible for drafting and ratifying the U.S. Constitution, generally favored the idea of a stronger, more centralized republic that had greater control over regulating the economy.[1]

Anti-Federalists preferred a more confederate system built on state equality and autonomy.[2]

The Federalist faction, led by Alexander Hamilton, largely dominated the government in the years immediately after the Constitution was ratified. Included in the Federalists was President George Washington, who was initially against the existence of parties in the United States. When Washington decided to exit politics and leave office, he warned of the potential negative effects of parties in his farewell address to the nation, including their potentially divisive nature and the fact that they might not always focus on the common good but rather on partisan ends. However, members of each faction quickly realized that they had a vested interest not only in nominating and electing a president who shared their views, but also in winning other elections. Two loosely affiliated party coalitions, known as the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans, soon emerged. The Federalists succeeded in electing their first leader, John Adams, to the presidency in 1796, only to see the Democratic-Republicans gain victory under Thomas Jefferson four years later in 1800.

|

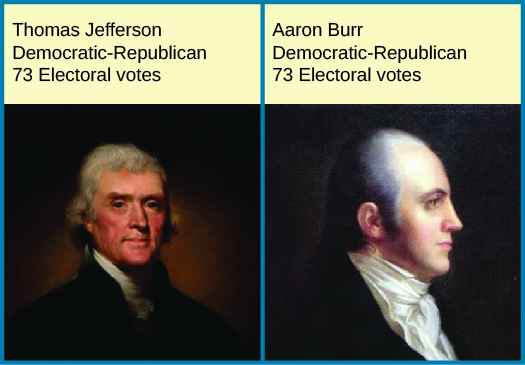

The “Revolution of 1800”: Uniting the Executive Branch under One Party When the U.S. Constitution was drafted, its authors were certainly aware that political parties existed in other countries (like Great Britain), but they hoped to avoid them in the United States. They felt the importance of states in the U.S. federal structure would make it difficult for national parties to form. They also hoped that having a college of electors vote for the executive branch, with the top two vote-getters becoming president and vice president, would discourage the formation of parties. Their system worked for the first two presidential elections, when essentially all the electors voted for George Washington to serve as president. But by 1796, the Federalist and Anti-Federalist camps had organized into electoral coalitions. The Anti-Federalists joined with many others active in the process to become known as the Democratic-Republicans. The Federalist John Adams won the Electoral College vote, but his authority was undermined when the vice presidency went to Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson, who finished second. Four years later, the Democratic-Republicans managed to avoid this outcome by coordinating the electors to vote for their top two candidates. But when the vote ended in a tie, it was ultimately left to Congress to decide who would be the third president of the United States ((Figure)).  Figure 2. Thomas Jefferson almost lost the presidential election of 1800 to his own running mate when a flaw in the design of the Electoral College led to a tie that had to be resolved by Congress. In an effort to prevent a similar outcome in the future, Congress and the states voted to ratify the Twelfth Amendment, which went into effect in 1804. This amendment changed the rules so that the president and vice president would be selected through separate elections within the Electoral College, and it altered the method that Congress used to fill the offices in the event that no candidate won a majority. The amendment essentially endorsed the new party system and helped prevent future controversies. It also served as an early effort by the two parties to collude to make it harder for an outsider to win the presidency. Does the process of selecting the executive branch need to be reformed so that the people elect the president and vice president directly, rather than through the Electoral College? Should the people vote separately on each office rather than voting for both at the same time? Explain your reasoning. |

Growing regional tensions eroded the Federalist Party’s ability to coordinate elites, and it eventually collapsed following its opposition to the War of 1812.[3]

The Democratic-Republican Party, on the other hand, eventually divided over whether national resources should be focused on economic and mercantile development, such as tariffs on imported goods and government funding of internal improvements like roads and canals, or on promoting populist issues that would help the “common man,” such as reducing or eliminating state property requirements that had prevented many men from voting.[4]

In the election of 1824, numerous candidates contended for the presidency, all members of the Democratic-Republican Party. Andrew Jackson won more popular votes and more votes in the Electoral College than any other candidate. However, because he did not win the majority (more than half) of the available electoral votes, the election was decided by the House of Representatives, as required by the Twelfth Amendment. The Twelfth Amendment limited the House’s choice to the three candidates with the greatest number of electoral votes. Thus, Andrew Jackson, with 99 electoral votes, found himself in competition with only John Quincy Adams, the second place finisher with 84 electoral votes, and William H. Crawford, who had come in third with 41. The fourth-place finisher, Henry Clay, who was no longer in contention, had won 37 electoral votes. Clay strongly disliked Jackson, and his ideas on government support for tariffs and internal improvements were similar to those of Adams. Clay thus gave his support to Adams, who was chosen on the first ballot. Jackson considered the actions of Clay and Adams, the son of the Federalist president John Adams, to be an unjust triumph of supporters of the elite and referred to it as “the corrupt bargain.”[5]

This marked the beginning of what historians call the Second Party System (the first parties had been the Federalists and the Jeffersonian Republicans), with the splitting of the Democratic-Republicans and the formation of two new political parties. One half, called simply the Democratic Party, was the party of Jackson; it continued to advocate for the common people by championing westward expansion and opposing a national bank. The branch of the Democratic-Republicans that believed that the national government should encourage economic (primarily industrial) development was briefly known as the National Republicans and later became the Whig Party[6]. In the election of 1828, Democrat Andrew Jackson was triumphant. Three times as many people voted in 1828 as had in 1824, and most cast their ballots for him.[7]

The formation of the Democratic Party marked an important shift in U.S. politics. Rather than being built largely to coordinate elite behavior, the Democratic Party worked to organize the electorate by taking advantage of state-level laws that had extended suffrage from male property owners to nearly all white men.[8]

This change marked the birth of what is often considered the first modern political party in any democracy in the world.[9]

It also dramatically changed the way party politics was, and still is, conducted. For one thing, this new party organization was built to include structures that focused on organizing and mobilizing voters for elections at all levels of government. The party also perfected an existing spoils system, in which support for the party during elections was rewarded with jobs in the government bureaucracy after victory.[10]

Many of these positions were given to party bosses and their friends. These men were the leaders of political machines, organizations that secured votes for the party’s candidates or supported the party in other ways. Perhaps more importantly, this election-focused organization also sought to maintain power by creating a broader coalition and thereby expanding the range of issues upon which the party was constructed.[11]

Each of the two main U.S. political parties today—the Democrats and the Republicans—maintains an extensive website with links to its affiliated statewide organizations, which in turn often maintain links to the party’s country organizations.

By comparison, here are websites for the Green Party and the Libertarian Party that are two other parties in the United States today.

The Democratic Party emphasized personal politics, which focused on building direct relationships with voters rather than on promoting specific issues. This party dominated national politics from Andrew Jackson’s presidential victory in 1828 until the mid-1850s, when regional tensions began to threaten the nation’s very existence. The growing power of industrialists, who preferred greater national authority, combined with increasing tensions between the northern and southern states over slavery, led to the rise of the Republican Party and its leader Abraham Lincoln in the election of 1860, while the Democratic Party dominated in the South. Like the Democrats, the Republicans also began to utilize a mass approach to party design and organization. Their opposition to the expansion of slavery, and their role in helping to stabilize the Union during Reconstruction, made them the dominant player in national politics for the next several decades.[12]

The Democratic and Republican parties have remained the two dominant players in the U.S. party system since the Civil War (1861–1865). That does not mean, however, that the system has been stagnant. Every political actor and every citizen has the ability to determine for him- or herself whether one of the two parties meets his or her needs and provides an appealing set of policy options, or whether another option is preferable.

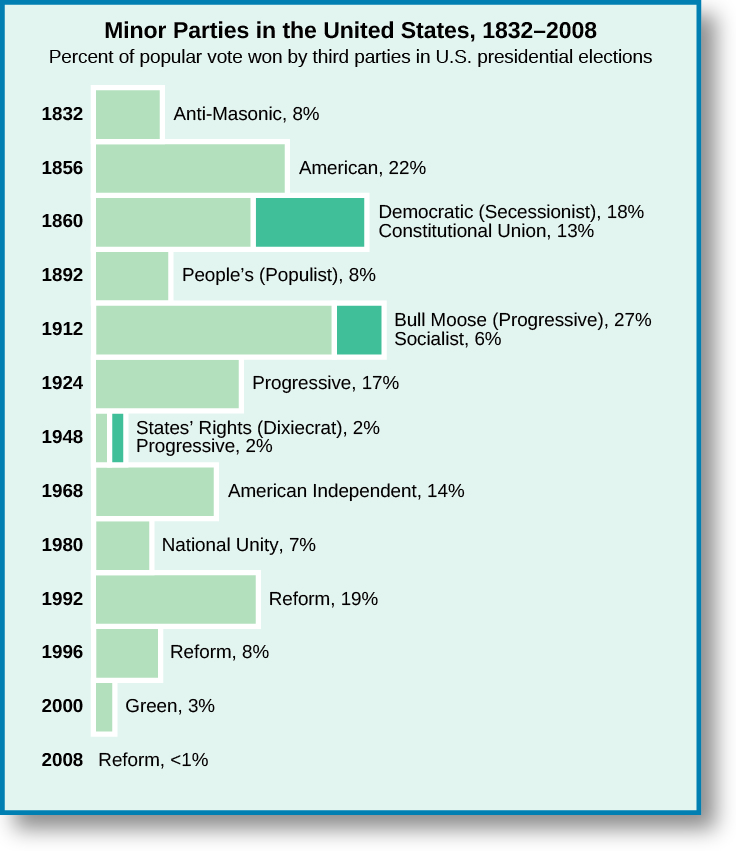

At various points in the past 170 years, elites and voters have sought to create alternatives to the existing party system. Political parties that are formed as alternatives to the Republican and Democratic parties are known as third parties, or minor parties ((Figure)). In 1892, a third party known as the Populist Party formed in reaction to what its constituents perceived as the domination of U.S. society by big business and a decline in the power of farmers and rural communities. The Populist Party called for the regulation of railroads, an income tax, and the popular election of U.S. senators, who at this time were chosen by state legislatures and not by ordinary voters.[13]

The party’s candidate in the 1892 elections, James B. Weaver, did not perform as well as the two main party candidates, and, in the presidential election of 1896, the Populists supported the Democratic candidate William Jennings Bryan. Bryan lost, and the Populists once again nominated their own presidential candidates in 1900, 1904, and 1908. The party disappeared from the national scene after 1908, but its ideas were similar to those of the Progressive Party, a new political party created in 1912.

Figure 3. Various third parties, also known as minor parties, have appeared in the United States over the years. Some, like the Socialist Party, still exist in one form or another. Others, like the Anti-Masonic Party, which wanted to protect the United States from the influence of the Masonic fraternal order and garnered just under 8 percent of the popular vote in 1832, are gone.

In 1912, former Republican president Theodore Roosevelt attempted to form a third party, known as the Progressive Party, as an alternative to the more business-minded Republicans. The Progressives sought to correct the many problems that had arisen as the United States transformed itself from a rural, agricultural nation into an increasingly urbanized, industrialized country dominated by big business interests. Among the reforms that the Progressive Party called for in its 1912 platform were women’s suffrage, an eight-hour workday, and workers’ compensation. The party also favored some of the same reforms as the Populist Party, such as the direct election of U.S. senators and an income tax, although Populists tended to be farmers while the Progressives were from the middle class. In general, Progressives sought to make government more responsive to the will of the people and to end political corruption in government. They wished to break the power of party bosses and political machines, and called upon states to pass laws allowing voters to vote directly on proposed legislation, propose new laws, and recall from office incompetent or corrupt elected officials. The Progressive Party largely disappeared after 1916, and most members returned to the Republican Party.[14]

The party enjoyed a brief resurgence in 1924, when Robert “Fighting Bob” La Follette ran unsuccessfully for president under the Progressive banner.

In 1948, two new third parties appeared on the political scene. Henry A. Wallace, a vice president under Franklin Roosevelt, formed a new Progressive Party, which had little in common with the earlier Progressive Party. Wallace favored racial desegregation and believed that the United States should have closer ties to the Soviet Union. Wallace’s campaign was a failure, largely because most people believed his policies, including national healthcare, were too much like those of communism, and this party also vanished. The other third party, the States’ Rights Democrats, also known as the Dixiecrats, were white, southern Democrats who split from the Democratic Party when Harry Truman, who favored civil rights for African Americans, became the party’s nominee for president. The Dixiecrats opposed all attempts by the federal government to end segregation, extend voting rights, prohibit discrimination in employment, or otherwise promote social equality among races.[15]

They remained a significant party that threatened Democratic unity throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Other examples of third parties in the United States include the American Independent Party, the Libertarian Party, United We Stand America, the Reform Party, and the Green Party.

None of these alternatives to the two major political parties had much success at the national level, and most are no longer viable parties. All faced the same fate. Formed by charismatic leaders, each championed a relatively narrow set of causes and failed to gain broad support among the electorate. Once their leaders had been defeated or discredited, the party structures that were built to contest elections collapsed. And within a few years, most of their supporters were eventually pulled back into one of the existing parties. To be sure, some of these parties had an electoral impact. For example, the Progressive Party pulled enough votes away from the Republicans to hand the 1912 election to the Democrats. Thus, the third-party rival’s principal accomplishment was helping its least-preferred major party win, usually at the short-term expense of the very issue it championed. In the long run, however, many third parties have brought important issues to the attention of the major parties, which then incorporated these issues into their platforms. Understanding why this is the case is an important next step in learning about the issues and strategies of the modern Republican and Democratic parties. In the next section, we look at why the United States has historically been dominated by only two political parties.

Summary

Political parties are vital to the operation of any democracy. Early U.S. political parties were formed by national elites who disagreed over how to divide power between the national and state governments. The system we have today, divided between Republicans and Democrats, had consolidated by 1860. A number of minor parties have attempted to challenge the status quo, but they have largely failed to gain traction despite having an occasional impact on the national political scene.

| NOTE: The activities below will not be counted towards your final grade for this class. They are strictly here to help you check your knowledge in preparation for class assignments and future dialogue. Best of luck! |

Glossary

- party platform

- the collection of a party’s positions on issues it considers politically important

- personal politics

- a political style that focuses on building direct relationships with voters rather than on promoting specific issues

- political machine

- an organization that secures votes for a party’s candidates or supports the party in other ways, usually in exchange for political favors such as a job in government

- political parties

- organizations made up of groups of people with similar interests that try to directly influence public policy through their members who seek and hold public office

- third parties

- political parties formed as an alternative to the Republican and Democratic parties, also known as minor parties

- Larry Sabato and Howard R. Ernst. 2007. Encyclopedia of American Political Parties and Elections. New York: Checkmark Books, 151. ↵

- Saul Cornell. 2016. The Other Founders: Anti-Federalism and the Dissenting Tradition in America. Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press, 11. ↵

- James H. Ellis. 2009. A Ruinous and Unhappy War: New England and the War of 1812. New York: Algora Publishing, 80. ↵

- Alexander Keyssar. 2009. The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States. New York: Basic Books. ↵

- R. R. Stenberg, “Jackson, Buchanan, and the “Corrupt Bargain” Calumny,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 58, no. 1 (1934): 61–85. ↵

- 2009. “Democratic-Republican Party,” In UXL Encyclopedia of U.S. History, eds. Sonia Benson, Daniel E. Brannen, Jr., and Rebecca Valentine. Detroit: UXL, 435–436; “Jacksonian Democracy and Modern America,” http://www.ushistory.org/us/23f.asp (March 6, 2016). ↵

- Virginia Historical Society. “Elections from 1789–1828.” http://www.vahistorical.org/collections-and-resources/virginia-history-explorer/getting-message-out-presidential-campaign-0 (March 11, 2016). ↵

- William G. Shade. 1983. “The Second Party System.” In Evolution of American Electoral Systems, eds. Paul Kleppner, et al. Westport, CT: Greenwood Pres, 77–111. ↵

- Jules Witcover. 2003. Party of the People: A History of the Democrats. New York: Random House, 3. ↵

- Daniel Walker Howe. 2007. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. New York: Oxford University Press, 330-34. ↵

- Sean Wilentz. 2006. The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln. New York: Norton. ↵

- Calvin Jillson. 1994. “Patterns and Periodicity.” In The Dynamics of American Politics: Approaches and Interpretations, eds. Lawrence C. Dodd and Calvin C. Jillson. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 38–41. ↵

- Norman Pollack. 1976. The Populist Response to Industrial America: Midwestern Populist Thought. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 11–12. ↵

- 1985. Congressional Quarterly’s Guide to U.S. Elections. Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly Inc., 75–78, 387–388. ↵

- “Platform of the States Rights Democratic Party,” http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=25851 (March 12, 2016). ↵