Chapter 6: The Politics of Public Opinion

The Nature of Public Opinion

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define public opinion and political socialization

- Explain the process and role of political socialization in the U.S. political system

- Compare the ways in which citizens learn political information

- Explain how beliefs and ideology affect the formation of public opinion

The collection of public opinion through polling and interviews is a part of American political culture. Politicians want to know what the public thinks. Campaign managers want to know how citizens will vote. Media members seek to write stories about what Americans want. Every day, polls take the pulse of the people and report the results. And yet we have to wonder: Why do we care what people think?

WHAT IS PUBLIC OPINION?

Public opinion is a collection of popular views about something, perhaps a person, a local or national event, or a new idea. For example, each day, a number of polling companies call Americans at random to ask whether they approve or disapprove of the way the president is guiding the economy.[1]

When situations arise internationally, polling companies survey whether citizens support U.S. intervention in places like Syria or Ukraine. These individual opinions are collected together to be analyzed and interpreted for politicians and the media. The analysis examines how the public feels or thinks, so politicians can use the information to make decisions about their future legislative votes, campaign messages, or propaganda.

But where do people’s opinions come from? Most citizens base their political opinions on their beliefs[2] and their attitudes, both of which begin to form in childhood. Beliefs are closely held ideas that support our values and expectations about life and politics. For example, the idea that we are all entitled to equality, liberty, freedom, and privacy is a belief most people in the United States share. We may acquire this belief by growing up in the United States or by having come from a country that did not afford these valued principles to its citizens.

Our attitudes are also affected by our personal beliefs and represent the preferences we form based on our life experiences and values. A person who has suffered racism or bigotry may have a skeptical attitude toward the actions of authority figures, for example.

Over time, our beliefs and our attitudes about people, events, and ideas will become a set of norms, or accepted ideas, about what we may feel should happen in our society or what is right for the government to do in a situation. In this way, attitudes and beliefs form the foundation for opinions.

POLITICAL SOCIALIZATION

At the same time that our beliefs and attitudes are forming during childhood, we are also being socialized; that is, we are learning from many information sources about the society and community in which we live and how we are to behave in it. Political socialization is the process by which we are trained to understand and join a country’s political world, and, like most forms of socialization, it starts when we are very young. We may first become aware of politics by watching a parent or guardian vote, for instance, or by hearing presidents and candidates speak on television or the Internet, or seeing adults honor the American flag at an event ((Figure)). As socialization continues, we are introduced to basic political information in school. We recite the Pledge of Allegiance and learn about the Founding Fathers, the Constitution, the two major political parties, the three branches of government, and the economic system.

Figure 1. Political socialization begins early. Hans Enoksen, former prime minister of Greenland, receives a helping hand at the polls from five-year-old Pipaluk Petersen (a). Intelligence Specialist Second Class Tashawbaba McHerrin (b) hands a U.S. flag to a child visiting the USS Enterprise during Fleet Week in Port Everglades, Florida. (credit a: modification of work by Leiff Josefsen; credit b: modification of work by Matthew Keane, U.S. Navy)

By the time we complete school, we have usually acquired the information necessary to form political views and be contributing members of the political system. A young man may realize he prefers the Democratic Party because it supports his views on social programs and education, whereas a young woman may decide she wants to vote for the Republican Party because its platform echoes her beliefs about economic growth and family values.

Accounting for the process of socialization is central to our understanding of public opinion, because the beliefs we acquire early in life are unlikely to change dramatically as we grow older.[3]

Our political ideology, made up of the attitudes and beliefs that help shape our opinions on political theory and policy, is rooted in who we are as individuals. Our ideology may change subtly as we grow older and are introduced to new circumstances or new information, but our underlying beliefs and attitudes are unlikely to change very much, unless we experience events that profoundly affect us. For example, family members of 9/11 victims became more Republican and more political following the terrorist attacks.[4]

Similarly, young adults who attended political protest rallies in the 1960s and 1970s were more likely to participate in politics in general than their peers who had not protested.[5]

If enough beliefs or attitudes are shattered by an event, such as an economic catastrophe or a threat to personal safety, ideology shifts may affect the way we vote. During the 1920s, the Republican Party controlled the House of Representatives and the Senate, sometimes by wide margins.[6]

After the stock market collapsed and the nation slid into the Great Depression, many citizens abandoned the Republican Party. In 1932, voters overwhelmingly chose Democratic candidates, for both the presidency and Congress. The Democratic Party gained registered members and the Republican Party lost them.[7]

Citizens’ beliefs had shifted enough to cause the control of Congress to change from one party to the other, and Democrats continued to hold Congress for several decades. Another sea change occurred in Congress in the 1994 elections when the Republican Party took control of both the House and the Senate for the first time in over forty years.

Today, polling agencies have noticed that citizens’ beliefs have become far more polarized, or widely opposed, over the last decade.[8]

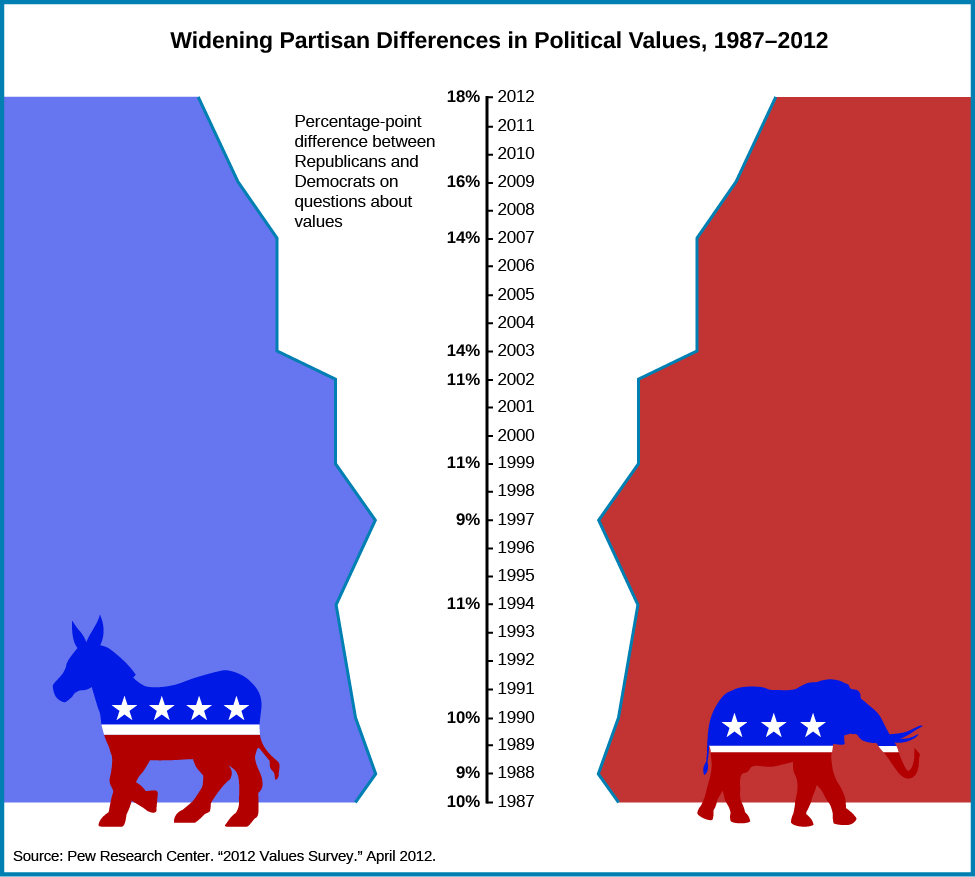

To track this polarization, Pew Research conducted a study of Republican and Democratic respondents over a twenty-five-year span. Every few years, Pew would poll respondents, asking them whether they agreed or disagreed with statements. These statements are referred to as “value questions” or “value statements,” because they measure what the respondent values. Examples of statements include “Government regulation of business usually does more harm than good,” “Labor unions are necessary to protect the working person,” and “Society should ensure all have equal opportunity to succeed.” After comparing such answers for twenty-five years, Pew Research found that Republican and Democratic respondents are increasingly answering these questions very differently. This is especially true for questions about the government and politics. In 1987, 58 percent of Democrats and 60 percent of Republicans agreed with the statement that the government controlled too much of our daily lives. In 2012, 47 percent of Democrats and 77 percent of Republicans agreed with the statement. This is an example of polarization, in which members of one party see government from a very different perspective than the members of the other party ((Figure)).[9]

Figure 2. Over the years, Democrats and Republicans have moved further apart in their beliefs about the role of government. In 1987, Republican and Democratic answers to forty-eight values questions differed by an average of only 10 percent, but that difference has grown to 18 percent over the last twenty-five years.

Political scientists noted this and other changes in beliefs following the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States, including an increase in the level of trust in government[10] and a new willingness to limit liberties for groups or citizens who “[did] not fit into the dominant cultural type.”[11]

According to some scholars, these shifts led partisanship to become more polarized than in previous decades, as more citizens began thinking of themselves as conservative or liberal rather than moderate.[12]

Some believe 9/11 caused a number of citizens to become more conservative overall, although it is hard to judge whether such a shift will be permanent.[13]

SOCIALIZATION AGENTS

An agent of political socialization is a source of political information intended to help citizens understand how to act in their political system and how to make decisions on political matters. The information may help a citizen decide how to vote, where to donate money, or how to protest decisions made by the government.

The most prominent agents of socialization are family and school. Other influential agents are social groups, such as religious institutions and friends, and the media. Political socialization is not unique to the United States. Many nations have realized the benefits of socializing their populations. China, for example, stresses nationalism in schools as a way to increase national unity.[14]

In the United States, one benefit of socialization is that our political system enjoys diffuse support, which is support characterized by a high level of stability in politics, acceptance of the government as legitimate, and a common goal of preserving the system.[15]

These traits keep a country steady, even during times of political or social upheaval. But diffuse support does not happen quickly, nor does it occur without the help of agents of political socialization.

For many children, family is the first introduction to politics. Children may hear adult conversations at home and piece together the political messages their parents support. They often know how their parents or grandparents plan to vote, which in turn can socialize them into political behavior such as political party membership.[16]

Children who accompany their parents on Election Day in November are exposed to the act of voting and the concept of civic duty, which is the performance of actions that benefit the country or community. Families active in community projects or politics make children aware of community needs and politics.

Introducing children to these activities has an impact on their future behavior. Both early and recent findings suggest that children adopt some of the political beliefs and attitudes of their parents ((Figure)).[17]

Children of Democratic parents often become registered Democrats, whereas children in Republican households often become Republicans. Children living in households where parents do not display a consistent political party loyalty are less likely to be strong Democrats or strong Republicans, and instead are often independents.[18]

![Chart shows the percentage intergenerational resemblance in partisan orientation in 1992. People who identify as strong democrat reported their parents’ political orientation as follows: 31% reported both of their parents as democrats, 6% reported both of their parents as republicans, and 10% reported no consistent partisanship among parents. Weak democrats reported their parents’ political orientation as follows: 27% reported both parents as democrat, 6% reported both their parents as republicans, and 14% reported no consistent partisanship among parents. Independent democrats reported their parents’ political orientation as follows: 14% reported both parents as democrats, 6% reported both parents as republicans, and 18% reported no consistent partisanship among parents. Pure independents reported their parents’ political orientation as follows: 7% reported both parents as democrats. 7% reported both parents as republicans. 17% reported no consistent partisanship among parents. Independent republicans reported their parents’ political orientation as follows: 7% reported both parents as democrats, 16% reported both parents as republicans. 16% reported no consistent partisanship among parents. Weak republicans reported their parents’ political orientation as follows: 8% reported both parents as democrats, 32% reported both parents as republicans, 14% reported no consistent partisanship among parents. Strong republicans reported their parents’ political orientation as follows: 6% reported both parents as democrats, 27% report both parents as republicans, and 9% reported no consistent partisanship among parents. At the bottom of the chart, a source is cited: “Miller, Warren E., Donald R. Kinder, Steven J. Rosenstone, and National Election Studies. American National Election Study, 1992: Pre- and Post-Election Survey [Enhanced with 1990 and 1991 Data]. ICPSR06067-v2. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor], 1999. http://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR06067.v2”.](https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/app/uploads/sites/4/2017/12/OSC_AmGov_06_01_PartisLink.jpg)

Figure 3. A parent’s political orientation often affects the political orientation of his or her child.

While family provides an informal political education, schools offer a more formal and increasingly important one. The early introduction is often broad and thematic, covering explorers, presidents, victories, and symbols, but generally the lessons are idealized and do not discuss many of the specific problems or controversies connected with historical figures and moments. George Washington’s contributions as our first president are highlighted, for instance, but teachers are unlikely to mention that he owned slaves. Lessons will also try to personalize government and make leaders relatable to children. A teacher might discuss Abraham Lincoln’s childhood struggle to get an education despite the death of his mother and his family’s poverty. Children learn to respect government, follow laws, and obey the requests of police, firefighters, and other first responders. The Pledge of Allegiance becomes a regular part of the school day, as students learn to show respect to our country’s symbols such as the flag and to abstractions such as liberty and equality.

As students progress to higher grades, lessons will cover more detailed information about the history of the United States, its economic system, and the workings of the government. Complex topics such as the legislative process, checks and balances, and domestic policymaking are covered. Introductory economics classes teach about the various ways to build an economy, explaining how the capitalist system works. Many high schools have implemented civic volunteerism requirements as a way to encourage students to participate in their communities. Many offer Advanced Placement classes in U.S. government and history, or other honors-level courses, such as International Baccalaureate or dual-credit courses. These courses can introduce detail and realism, raise controversial topics, and encourage students to make comparisons and think critically about the United States in a global and historical context. College students may choose to pursue their academic study of the U.S. political system further, become active in campus advocacy or rights groups, or run for any of a number of elected positions on campus or even in the local community. Each step of the educational system’s socialization process will ready students to make decisions and be participating members of political society.

We are also socialized outside our homes and schools. When citizens attend religious ceremonies, as 70 percent of Americans in a recent survey claimed,[19] they are socialized to adopt beliefs that affect their politics. Religion leaders often teach on matters of life, death, punishment, and obligation, which translate into views on political issues such as abortion, euthanasia, the death penalty, and military involvement abroad. Political candidates speak at religious centers and institutions in an effort to meet like-minded voters. For example, Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) announced his 2016 presidential bid at Liberty University, a fundamentalist Christian institution. This university matched Cruz’s conservative and religious ideological leanings and was intended to give him a boost from the faith-based community.

Friends and peers too have a socializing effect on citizens. Communication networks are based on trust and common interests, so when we receive information from friends and neighbors, we often readily accept it because we trust them.[20]

Information transmitted through social media like Facebook is also likely to have a socializing effect. Friends “like” articles and information, sharing their political beliefs and information with one another.

Media—newspapers, television, radio, and the Internet—also socialize citizens through the information they provide. For a long time, the media served as gatekeepers of our information, creating reality by choosing what to present. If the media did not cover an issue or event, it was as if it did not exist. With the rise of the Internet and social media, however, traditional media have become less powerful agents of this kind of socialization.

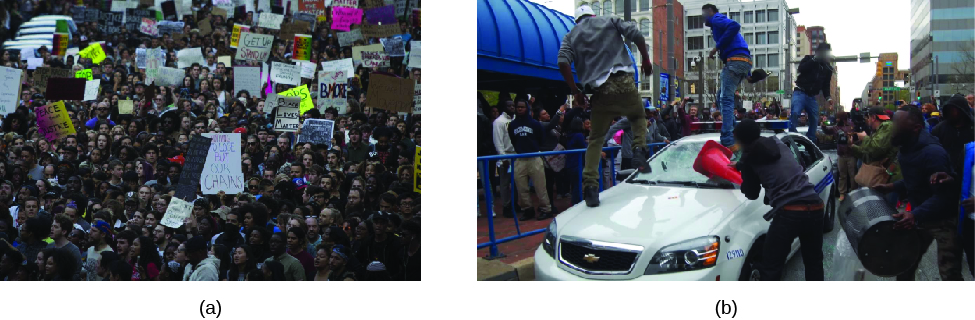

Another way the media socializes audiences is through framing, or choosing the way information is presented. Framing can affect the way an event or story is perceived. Candidates described with negative adjectives, for instance, may do poorly on Election Day. Consider the recent demonstrations over the deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and of Freddie Gray in Baltimore, Maryland. Both deaths were caused by police actions against unarmed African American men. Brown was shot to death by an officer on August 9, 2014. Gray died from spinal injuries sustained in transport to jail in April 2015. Following each death, family, friends, and sympathizers protested the police actions as excessive and unfair. While some television stations framed the demonstrations as riots and looting, other stations framed them as protests and fights against corruption. The demonstrations contained both riot and protest, but individuals’ perceptions were affected by the framing chosen by their preferred information sources ((Figure)).[21]

Figure 4. Images of protestors from the Baltimore “uprising” (a) and from the Baltimore “riots” (b) of April 25, 2015. (credit a: modification of work by Pete Santilli Live Stream/YouTube; credit b: modification of work by “Newzulu”/YouTube)

Finally, media information presented as fact can contain covert or overt political material. Covert content is political information provided under the pretense that it is neutral. A magazine might run a story on climate change by interviewing representatives of only one side of the policy debate and downplaying the opposing view, all without acknowledging the one-sided nature of its coverage. In contrast, when the writer or publication makes clear to the reader or viewer that the information offers only one side of the political debate, the political message is overt content. Political commentators like Rush Limbaugh and publications like Mother Jones openly state their ideological viewpoints. While such overt political content may be offensive or annoying to a reader or viewer, all are offered the choice whether to be exposed to the material.

SOCIALIZATION AND IDEOLOGY

The socialization process leaves citizens with attitudes and beliefs that create a personal ideology. Ideologies depend on attitudes and beliefs, and on the way we prioritize each belief over the others. Most citizens hold a great number of beliefs and attitudes about government action. Many think government should provide for the common defense, in the form of a national military. They also argue that government should provide services to its citizens in the form of free education, unemployment benefits, and assistance for the poor.

When asked how to divide the national budget, Americans reveal priorities that divide public opinion. Should we have a smaller military and larger social benefits, or a larger military budget and limited social benefits? This is the guns versus butter debate, which assumes that governments have a finite amount of money and must choose whether to spend a larger part on the military or on social programs. The choice forces citizens into two opposing groups.

Divisions like these appear throughout public opinion. Assume we have four different people named Garcia, Chin, Smith, and Dupree. Garcia may believe that the United States should provide a free education for every citizen all the way through college, whereas Chin may believe education should be free only through high school. Smith might believe children should be covered by health insurance at the government’s expense, whereas Dupree believes all citizens should be covered. In the end, the way we prioritize our beliefs and what we decide is most important to us determines whether we are on the liberal or conservative end of the political spectrum, or somewhere in between.

|

Express Yourself You can volunteer to participate in public opinion surveys. Diverse respondents are needed across a variety of topics to give a reliable picture of what Americans think about politics, entertainment, marketing, and more. One polling group, Harris Interactive, maintains an Internet pool of potential respondents of varied ages, education levels, backgrounds, cultures, and more. When a survey is designed and put out into the field, Harris emails an invitation to the pool to find respondents. Respondents choose which surveys to complete based on the topics, time required, and compensation offered (usually small). Harris Interactive is a subsidiary of Nielsen, a company with a long history of measuring television and media viewership in the United States and abroad. Nielsen ratings help television stations identify shows and newscasts with enough viewers to warrant being kept in production, and also to set advertising rates (based on audience size) for commercials on popular shows. Harris Interactive has expanded Nielsen’s survey methods by using polling data and interviews to better predict future political and market trends. Harris polls cover the economy, lifestyles, sports, international affairs, and more. Which topic has the most surveys? Politics, of course. Wondering what types of surveys you might get? The results of some of the surveys will give you an idea. They are available to the public on the Harris website. For more information, log in to Harris Poll Online. |

IDEOLOGIES AND THE IDEOLOGICAL SPECTRUM

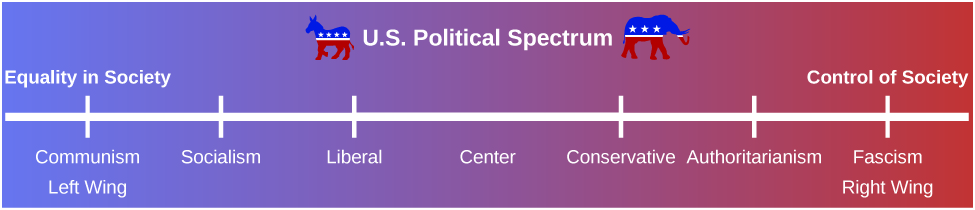

One useful way to look at ideologies is to place them on a spectrum that visually compares them based on what they prioritize. Liberal ideologies are traditionally put on the left and conservative ideologies on the right. (This placement dates from the French Revolution and is why liberals are called left-wing and conservatives are called right-wing.) The ideologies at the ends of the spectrum are the most extreme; those in the middle are moderate. Thus, people who identify with left- and right-wing ideologies identify with beliefs to the left and right ends of the spectrum, while moderates balance the beliefs at the extremes of the spectrum.

In the United States, ideologies at the right side of the spectrum prioritize government control over personal freedoms. They range from fascism to authoritarianism to conservatism. Ideologies on the left side of the spectrum prioritize equality and range from communism to socialism to liberalism ((Figure)). Moderate ideologies fall in the middle and try to balance the two extremes.

Figure 5. People who espouse left-wing ideologies in the United States identify with beliefs on the left side of the spectrum that prioritize equality, whereas those on the right side of the spectrum emphasize control.

Fascism promotes total control of the country by the ruling party or political leader. This form of government will run the economy, the military, society, and culture, and often tries to control the private lives of its citizens. Authoritarian leaders control the politics, military, and government of a country, and often the economy as well.

Conservative governments attempt to hold tight to the traditions of a nation by balancing individual rights with the good of the community. Traditional conservatism supports the authority of the monarchy and the church, believing government provides the rule of law and maintains a society that is safe and organized. Modern conservatism differs from traditional conservatism in assuming elected government will guard individual liberties and provide laws. Modern conservatives also prefer a smaller government that stays out of the economy, allowing the market and business to determine prices, wages, and supply.

Classical liberalism believes in individual liberties and rights. It is based on the idea of free will, that people are born equal with the right to make decisions without government intervention. It views government with suspicion, since history includes many examples of monarchs and leaders who limited citizens’ rights. Today, modern liberalism focuses on equality and supports government intervention in society and the economy if it promotes equality. Liberals expect government to provide basic social and educational programs to help everyone have a chance to succeed.

Under socialism, the government uses its authority to promote social and economic equality within the country. Socialists believe government should provide everyone with expanded services and public programs, such as health care, subsidized housing and groceries, childhood education, and inexpensive college tuition. Socialism sees the government as a way to ensure all citizens receive both equal opportunities and equal outcomes. Citizens with more wealth are expected to contribute more to the state’s revenue through higher taxes that pay for services provided to all. Socialist countries are also likely to have higher minimum wages than non-socialist countries.

In theory, communism promotes common ownership of all property, means of production, and materials. This means that the government, or states, should own the property, farms, manufacturing, and businesses. By controlling these aspects of the economy, Communist governments can prevent the exploitation of workers while creating an equal society. Extreme inequality of income, in which some citizens earn millions of dollars a year and other citizens merely hundreds, is prevented by instituting wage controls or by abandoning currency altogether. Communism presents a problem, however, because the practice differs from the theory. The theory assumes the move to communism is supported and led by the proletariat, or the workers and citizens of a country.[22]

Human rights violations by governments of actual Communist countries make it appear the movement has been driven not by the people, but by leadership.

We can characterize economic variations on these ideologies by adding another dimension to the ideological spectrum above—whether we prefer that government control the state economy or stay out of it. The extremes are a command economy, such as existed in the former Soviet Russia, and a laissez-faire (“leave it alone”) economy, such as in the United States prior to the 1929 market crash, when banks and corporations were largely unregulated. Communism prioritizes control of both politics and economy, while libertarianism is its near-opposite. Libertarians believe in individual rights and limited government intervention in private life and personal economic decisions. Government exists to maintain freedom and life, so its main function is to ensure domestic peace and national defense. Libertarians also believe the national government should maintain a military in case of international threats, but that it should not engage in setting minimum wages or ruling in private matters, like same-sex marriage or the right to abortion.[23]

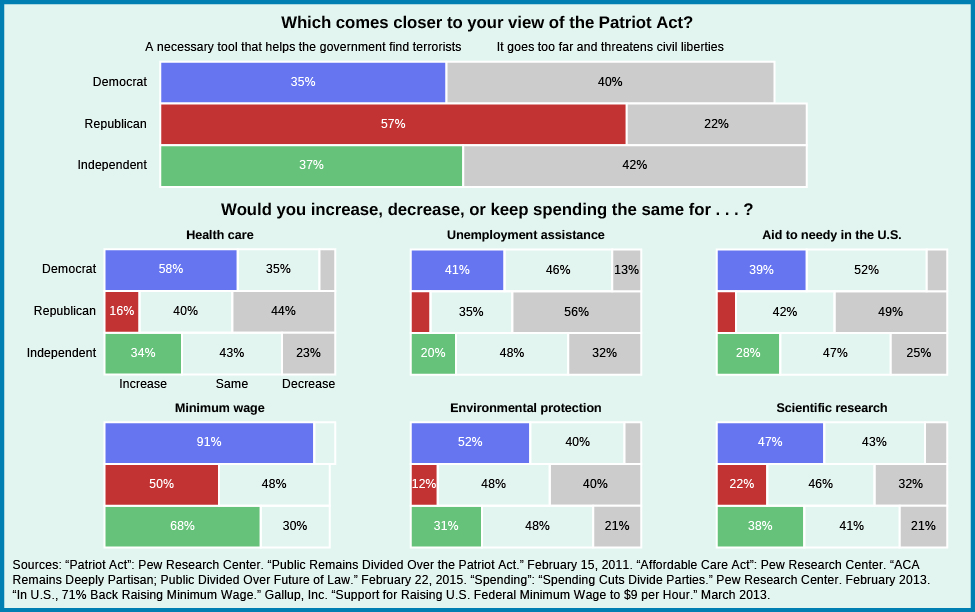

The point where a person’s ideology falls on the spectrum gives us some insight to his or her opinions. Though people can sometimes be liberal on one issue and conservative on another, a citizen to the left of liberalism, near socialism, would likely be happy with the passage of the Raise the Wage Act of 2015, which would eventually increase the minimum wage from $7.25 to $12 an hour. A citizen falling near conservatism would believe the Patriot Act is reasonable, because it allows the FBI and other government agencies to collect data on citizens’ phone calls and social media communications to monitor potential terrorism ((Figure)). A citizen to the right of the spectrum is more likely to favor cutting social services like unemployment and Medicaid.

Summary

Public opinion is more than a collection of answers to a question on a poll; it represents a snapshot of how people’s experiences and beliefs have led them to feel about a candidate, a law, or a social issue. Our attitudes are formed in childhood as part of our upbringing. They blend with our closely held beliefs about life and politics to form the basis for our opinions. Beginning early in life, we learn about politics from agents of socialization, which include family, schools, friends, religious organizations, and the media. Socialization gives us the information necessary to understand our political system and make decisions. We use this information to choose our ideology and decide what the proper role of government should be in our society.

| NOTE: The activities below will not be counted towards your final grade for this class. They are strictly here to help you check your knowledge in preparation for class assignments and future dialogue. Best of luck! |

Glossary

- agent of political socialization

- a person or entity that teaches and influences others about politics through use of information

- classical liberalism

- a political ideology based on belief in individual liberties and rights and the idea of free will, with little role for government

- communism

- a political and economic system in which, in theory, government promotes common ownership of all property, means of production, and materials to prevent the exploitation of workers while creating an equal society; in practice, most communist governments have used force to maintain control

- covert content

- ideologically slanted information presented as unbiased information in order to influence public opinion

- diffuse support

- the widespread belief that a country and its legal system are legitimate

- fascism

- a political system of total control by the ruling party or political leader over the economy, the military, society, and culture and often the private lives of citizens

- modern conservatism

- a political ideology that prioritizes individual liberties, preferring a smaller government that stays out of the economy

- modern liberalism

- a political ideology focused on equality and supporting government intervention in society and the economy if it promotes equality

- overt content

- political information whose author makes clear that only one side is presented

- political socialization

- the process of learning the norms and practices of a political system through others and societal institutions

- public opinion

- a collection of opinions of an individual or a group of individuals on a topic, person, or event

- socialism

- a political and economic system in which government uses its authority to promote social and economic equality, providing everyone with basic services and equal opportunities and requiring citizens with more wealth to contribute more

- traditional conservatism

- a political ideology supporting the authority of the monarchy and the church in the belief that government provides the rule of law

- Gallup. 2015. “Gallup Daily: Obama Job Approval.” Gallup. June 6, 2015. http://www.gallup.com/poll/113980/Gallup-Daily-Obama-Job-Approval.aspx (February 17, 2016); Rasmussen Reports. 2015. “Daily Presidential Tracking Poll.” Rasmussen Reports June 6, 2015. http://www.rasmussenreports.com/public_content/politics/obama_administration/daily_presidential_tracking_poll (February 17, 2016); Roper Center. 2015. “Obama Presidential Approval.” Roper Center. June 6, 2015. http://www.ropercenter.uconn.edu/polls/presidential-approval/ (February 17, 2016). ↵

- V. O. Key, Jr. 1966. The Responsible Electorate. Harvard University: Belknap Press. ↵

- John Zaller. 1992. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ↵

- Eitan Hersh. 2013. “Long-Term Effect of September 11 on the Political Behavior of Victims’ Families and Neighbors.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110 (52): 20959–63. ↵

- M. Kent Jennings. 2002. “Generation Units and the Student Protest Movement in the United States: An Intra- and Intergenerational Analysis.” Political Psychology 23 (2): 303–324. ↵

- United States Senate. 2015. “Party Division in the Senate, 1789-Present,” United States Senate. June 5, 2015. http://www.senate.gov/pagelayout/history/one_item_and_teasers/partydiv.htm (February 17, 2016). History, Art & Archives. 2015. “Party Divisions of the House of Representatives: 1789–Present.” United States House of Representatives. June 5, 2015. http://history.house.gov/Institution/Party-Divisions/Party-Divisions/ (February 17, 2016). ↵

- V. O. Key Jr. 1955. “A Theory of Critical Elections.” Journal of Politics 17 (1): 3–18. ↵

- Pew Research Center. 2014. “Political Polarization in the American Public.” Pew Research Center. June 12, 2014. http://www.people-press.org/2014/06/12/political-polarization-in-the-american-public/ (February 17, 2016). ↵

- Pew Research Center. 2015. “American Values Survey.” Pew Research Center. http://www.people-press.org/values-questions/ (February 17, 2016). ↵

- Virginia Chanley. 2002. “Trust in Government in the Aftermath of 9/11: Determinants and Consequences.” Political Psychology 23 (3): 469–483. ↵

- Deborah Schildkraut. 2002. “The More Things Change... American Identity and Mass and Elite Responses to 9/11.” Political Psychology 23 (3): 532. ↵

- Joseph Bafumi and Robert Shapiro. 2009. “A New Partisan Voter.” The Journal of Politics 71 (1): 1–24. ↵

- Liz Marlantes, “After 9/11, the Body Politic Tilts to Conservatism,” Christian Science Monitor, 16 January 2002. ↵

- Liping Weng. 2010. “Shanghai Children’s Value Socialization and Its Change: A Comparative Analysis of Primary School Textbooks.” China Media Research 6 (3): 36–43. ↵

- David Easton. 1965. A Systems Analysis of Political Life. New York: John Wiley. ↵

- Angus Campbell, Philip Converse, Warren Miller, and Donald Stokes. 2008. The American Voter: Unabridged Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Michael S. Lewis-Beck, William G. Jacoby, Helmut Norpoth, and Herbert F. Weisberg. 2008. American Vote Revisited. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ↵

- Russell Dalton. 1980. “Reassessing Parental Socialization: Indicator Unreliability versus Generational Transfer.” American Political Science Review 74 (2): 421–431. ↵

- Michael S. Lewis-Beck, William G. Jacoby, Helmut Norpoth, and Herbert F. Weisberg. 2008. American Vote Revisited. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ↵

- Michael Lipka. 2013. “What Surveys Say about Workshop Attendance—and Why Some Stay Home.” Pew Research Center. September 13, 2013. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/09/13/what-surveys-say-about-worship-attendance-and-why-some-stay-home/ (February 17, 2016). ↵

- Arthur Lupia and Mathew D. McCubbins. 1998. The Democratic Dilemma: Can Citizens Learn What They Need to Know? New York: Cambridge University Press. John Barry Ryan. 2011. “Social Networks as a Shortcut to Correct Voting.” American Journal of Political Science 55 (4): 753–766. ↵

- Sarah Bowen. 2015. “A Framing Analysis of Media Coverage of the Rodney King Incident and Ferguson, Missouri, Conflicts.” Elon Journal of Undergraduate Research in Communications 6 (1): 114–124. ↵

- Frederick Engels. 1847. The Principles of Communism. Trans. Paul Sweezy. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/11/prin-com.htm (February 17, 2016). ↵

- Libertarian Party. 2014. “Libertarian Party Platform.” June. http://www.lp.org/platform (February 17, 2016). ↵