Chapter 5: Civil Rights

The Fight for Women’s Rights

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe early efforts to achieve rights for women

- Explain why the Equal Rights Amendment failed to be ratified

- Describe the ways in which women acquired greater rights in the twentieth century

- Analyze why women continue to experience unequal treatment

Along with African Americans, women of all races and ethnicities have long been discriminated against in the United States, and the women’s rights movement began at the same time as the movement to abolish slavery in the United States. Indeed, the women’s movement came about largely as a result of the difficulties women encountered while trying to abolish slavery. The trailblazing Seneca Falls Convention for women’s rights was held in 1848, a few years before the Civil War. But the abolition and African American civil rights movements largely eclipsed the women’s movement throughout most of the nineteenth century. Women began to campaign actively again in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and another movement for women’s rights began in the 1960s.

THE EARLY WOMEN’S RIGHTS MOVEMENT AND WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE

At the time of the American Revolution, women had few rights. Although single women were allowed to own property, married women were not. When women married, their separate legal identities were erased under the legal principle of coverture. Not only did women adopt their husbands’ names, but all personal property they owned legally became their husbands’ property. Husbands could not sell their wives’ real property—such as land or in some states slaves—without their permission, but they were allowed to manage it and retain the profits. If women worked outside the home, their husbands were entitled to their wages.[1]

So long as a man provided food, clothing, and shelter for his wife, she was not legally allowed to leave him. Divorce was difficult and in some places impossible to obtain.[2]

Higher education for women was not available, and women were barred from professional positions in medicine, law, and ministry.

Following the Revolution, women’s conditions did not improve. Women were not granted the right to vote by any of the states except New Jersey, which at first allowed all taxpaying property owners to vote. However, in 1807, the law changed to limit the vote to men.[3]

Changes in property laws actually hurt women by making it easier for their husbands to sell their real property without their consent.

Although women had few rights, they nevertheless played an important role in transforming American society. This was especially true in the 1830s and 1840s, a time when numerous social reform movements swept across the United States. Many women were active in these causes, especially the abolition movement and the temperance movement, which tried to end the excessive consumption of liquor. They often found they were hindered in their efforts, however, either by the law or by widely held beliefs that they were weak, silly creatures who should leave important issues to men.[4]

One of the leaders of the early women’s movement, Elizabeth Cady Stanton ((Figure)), was shocked and angered when she sought to attend an 1840 antislavery meeting in London, only to learn that women would not be allowed to participate and had to sit apart from the men. At this convention, she made the acquaintance of another American female abolitionist, Lucretia Mott ((Figure)), who was also appalled by the male reformers’ treatment of women.[5]

Figure 1. Elizabeth Cady Stanton (a) and Lucretia Mott (b) both emerged from the abolitionist movement as strong advocates of women’s rights.

In 1848, Stanton and Mott called for a women’s rights convention, the first ever held specifically to address the subject, at Seneca Falls, New York. At the Seneca Falls Convention, Stanton wrote the Declaration of Sentiments, which was modeled after the Declaration of Independence and proclaimed women were equal to men and deserved the same rights. Among the rights Stanton wished to see granted to women was suffrage, the right to vote. When called upon to sign the Declaration, many of the delegates feared that if women demanded the right to vote, the movement would be considered too radical and its members would become a laughingstock. The Declaration passed, but the resolution demanding suffrage was the only one that did not pass unanimously.[6]

Along with other feminists (advocates of women’s equality), such as her friend and colleague Susan B. Anthony, Stanton fought for rights for women besides suffrage, including the right to seek higher education. As a result of their efforts, several states passed laws that allowed married women to retain control of their property and let divorced women keep custody of their children.[7]

Amelia Bloomer, another activist, also campaigned for dress reform, believing women could lead better lives and be more useful to society if they were not restricted by voluminous heavy skirts and tight corsets.

The women’s rights movement attracted many women who, like Stanton and Anthony, were active in either the temperance movement, the abolition movement, or both movements. Sarah and Angelina Grimke, the daughters of a wealthy slaveholding family in South Carolina, became first abolitionists and then women’s rights activists.[8]

Many of these women realized that their effectiveness as reformers was limited by laws that prohibited married women from signing contracts and by social proscriptions against women addressing male audiences. Without such rights, women found it difficult to rent halls in which to deliver lectures or to hire printers to produce antislavery literature.

Following the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, the women’s rights movement fragmented. Stanton and Anthony denounced the Fifteenth Amendment because it granted voting rights only to black men and not to women of any race.[9]

The fight for women’s rights did not die, however. In 1869, Stanton and Anthony formed the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), which demanded that the Constitution be amended to grant the right to vote to all women. It also called for more lenient divorce laws and an end to sex discrimination in employment. The less radical Lucy Stone formed the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) in the same year; AWSA hoped to win the suffrage for women by working on a state-by-state basis instead of seeking to amend the Constitution.[10]

Four western states—Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, and Idaho—did extend the right to vote to women in the late nineteenth century, but no other states did.

Women were also granted the right to vote on matters involving liquor licenses, in school board elections, and in municipal elections in several states. However, this was often done because of stereotyped beliefs that associated women with moral reform and concern for children, not as a result of a belief in women’s equality. Furthermore, voting in municipal elections was restricted to women who owned property.[11]

In 1890, the two suffragist groups united to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). To call attention to their cause, members circulated petitions, lobbied politicians, and held parades in which hundreds of women and girls marched through the streets ((Figure)).

Figure 2. In October 1917, suffragists marched down Fifth Avenue in New York demanding the right to vote. They carried a petition that had been signed by one million women.

The more radical National Woman’s Party (NWP), led by Alice Paul, advocated the use of stronger tactics. The NWP held public protests and picketed outside the White House ((Figure)).[12]

Demonstrators were often beaten and arrested, and suffragists were subjected to cruel treatment in jail. When some, like Paul, began hunger strikes to call attention to their cause, their jailers force-fed them, an incredibly painful and invasive experience for the women.[13]

Finally, in 1920, the triumphant passage of the Nineteenth Amendment granted all women the right to vote.

CIVIL RIGHTS AND THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT

Just as the passage of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments did not result in equality for African Americans, the Nineteenth Amendment did not end discrimination against women in education, employment, or other areas of life, which continued to be legal. Although women could vote, they very rarely ran for or held public office. Women continued to be underrepresented in the professions, and relatively few sought advanced degrees. Until the mid-twentieth century, the ideal in U.S. society was typically for women to marry, have children, and become housewives. Those who sought work for pay outside the home were routinely denied jobs because of their sex and, when they did find employment, were paid less than men. Women who wished to remain childless or limit the number of children they had in order to work or attend college found it difficult to do so. In some states it was illegal to sell contraceptive devices, and abortions were largely illegal and difficult for women to obtain.

A second women’s rights movement emerged in the 1960s to address these problems. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited discrimination in employment on the basis of sex as well as race, color, national origin, and religion. Nevertheless, women continued to be denied jobs because of their sex and were often sexually harassed at the workplace. In 1966, feminists who were angered by the lack of progress made by women and by the government’s lackluster enforcement of Title VII organized the National Organization for Women (NOW). NOW promoted workplace equality, including equal pay for women, and also called for the greater presence of women in public office, the professions, and graduate and professional degree programs.

NOW also declared its support for the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which mandated equal treatment for all regardless of sex. The ERA, written by Alice Paul and Crystal Eastman, was first proposed to Congress, unsuccessfully, in 1923. It was introduced in every Congress thereafter but did not pass both the House and the Senate until 1972. The amendment was then sent to the states for ratification with a deadline of March 22, 1979. Although many states ratified the amendment in 1972 and 1973, the ERA still lacked sufficient support as the deadline drew near. Opponents, including both women and men, argued that passage would subject women to military conscription and deny them alimony and custody of their children should they divorce.[14]

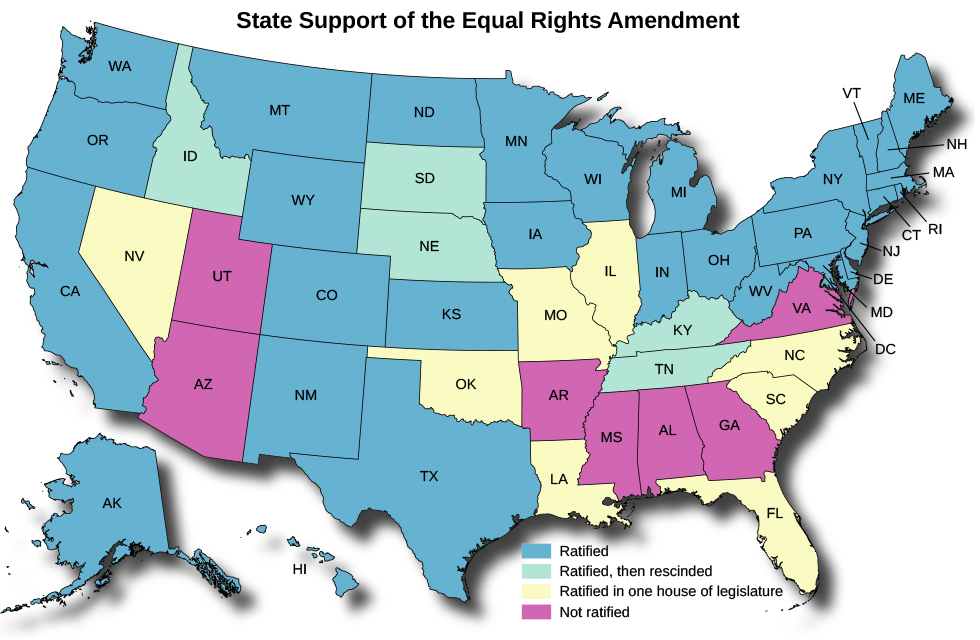

In 1978, Congress voted to extend the deadline for ratification to June 30, 1982. Even with the extension, however, the amendment failed to receive the support of the required thirty-eight states; by the time the deadline arrived, it had been ratified by only thirty-five, some of those had rescinded their ratifications, and no new state had ratified the ERA during the extension period ((Figure)).

Figure 4. The map shows which states supported the ERA and which did not. The dark blue states ratified the amendment. The amendment was ratified but later rescinded in the light blue states and was ratified in only one branch of the legislature in the yellow states. The ERA was never ratified by the purple states.

Although the ERA failed to be ratified, Title IX of the United States Education Amendments of 1972 passed into law as a federal statute (not as an amendment, as the ERA was meant to be). Title IX applies to all educational institutions that receive federal aid and prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in academic programs, dormitory space, health-care access, and school activities including sports. Thus, if a school receives federal aid, it cannot spend more funds on programs for men than on programs for women.

CONTINUING CHALLENGES FOR WOMEN

There is no doubt that women have made great progress since the Seneca Falls Convention. Today, more women than men attend college, and they are more likely than men to graduate.[15]

Women are represented in all the professions, and approximately half of all law and medical school students are women.[16]

Women have held Cabinet positions and have been elected to Congress. They have run for president and vice president, and three female justices currently serve on the Supreme Court. Women are also represented in all branches of the military and can serve in combat. As a result of the 1973 Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade, women now have legal access to abortion.[17]

Nevertheless, women are still underrepresented in some jobs and are less likely to hold executive positions than are men. Many believe the glass ceiling, an invisible barrier caused by discrimination, prevents women from rising to the highest levels of American organizations, including corporations, governments, academic institutions, and religious groups. Women earn less money than men for the same work. As of 2014, fully employed women earned seventy-nine cents for every dollar earned by a fully employed man.[18]

Women are also more likely to be single parents than are men.[19]

As a result, more women live below the poverty line than do men, and, as of 2012, households headed by single women are twice as likely to live below the poverty line than those headed by single men.[20]

Women remain underrepresented in elective offices. As of April 2016, women held only about 20 percent of seats in Congress and only about 25 percent of seats in state legislatures.[21]

Women remain subject to sexual harassment in the workplace and are more likely than men to be the victims of domestic violence. Approximately one-third of all women have experienced domestic violence; one in five women is assaulted during her college years.[22]

Many in the United States continue to call for a ban on abortion, and states have attempted to restrict women’s access to the procedure. For example, many states have required abortion clinics to meet the same standards set for hospitals, such as corridor size and parking lot capacity, despite lack of evidence regarding the benefits of such standards. Abortion clinics, which are smaller than hospitals, often cannot meet such standards. Other restrictions include mandated counseling before the procedure and the need for minors to secure parental permission before obtaining abortion services.[23]

Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt (2016) cited the lack of evidence for the benefit of larger clinics and further disallowed two Texas laws that imposed special requirements on doctors in order to perform abortions.[24]

Furthermore, the federal government will not pay for abortions for low-income women except in cases of rape or incest or in situations in which carrying the fetus to term would endanger the life of the mother.[25]

To address these issues, many have called for additional protections for women. These include laws mandating equal pay for equal work. According to the doctrine of comparable worth, people should be compensated equally for work requiring comparable skills, responsibilities, and effort. Thus, even though women are underrepresented in certain fields, they should receive the same wages as men if performing jobs requiring the same level of accountability, knowledge, skills, and/or working conditions, even though the specific job may be different.

For example, garbage collectors are largely male. The chief job requirements are the ability to drive a sanitation truck and to lift heavy bins and toss their contents into the back of truck. The average wage for a garbage collector is $15.34 an hour.[26]

Daycare workers are largely female, and the average pay is $9.12 an hour.[27]

However, the work arguably requires more skills and is a more responsible position. Daycare workers must be able to feed, clean, and dress small children; prepare meals for them; entertain them; give them medicine if required; and teach them basic skills. They must be educated in first aid and assume responsibility for the children’s safety. In terms of the skills and physical activity required and the associated level of responsibility of the job, daycare workers should be paid at least as much as garbage collectors and perhaps more. Women’s rights advocates also call for stricter enforcement of laws prohibiting sexual harassment, and for harsher punishment, such as mandatory arrest, for perpetrators of domestic violence.

|

Harry Burn and the Tennessee General Assembly In 1918, the proposed Nineteenth Amendment to the Constitution, extending the right to vote to all adult female citizens of the United States, was passed by both houses of Congress and sent to the states for ratification. Thirty-six votes were needed. Throughout 1918 and 1919, the Amendment dragged through legislature after legislature as pro- and anti-suffrage advocates made their arguments. By the summer of 1920, only one more state had to ratify it before it became law. The Amendment passed through Tennessee’s state Senate and went to its House of Representatives. Arguments were bitter and intense. Pro-suffrage advocates argued that the amendment would reward women for their service to the nation during World War I and that women’s supposedly greater morality would help to clean up politics. Those opposed claimed women would be degraded by entrance into the political arena and that their interests were already represented by their male relatives. On August 18, the amendment was brought for a vote before the House. The vote was closely divided, and it seemed unlikely it would pass. But as a young anti-suffrage representative waited for his vote to be counted, he remembered a note he had received from his mother that day. In it, she urged him, “Hurrah and vote for suffrage!” At the last minute, Harry Burn abruptly changed his ballot. The amendment passed the House by one vote, and eight days later, the Nineteenth Amendment was added to the Constitution. How are women perceived in politics today compared to the 1910s? What were the competing arguments for Harry Burn’s vote? |

Summary

| NOTE: The activities below will not be counted towards your final grade for this class. They are strictly here to help you check your knowledge in preparation for class assignments and future dialogue. Best of luck! |

Glossary

- comparable worth

- a doctrine calling for the same pay for workers whose jobs require the same level of education, responsibility, training, or working conditions

- coverture

- a legal status of married women in which their separate legal identities were erased

- Equal Rights Amendment (ERA)

- the proposed amendment to the Constitution that would have prohibited all discrimination based on sex

- glass ceiling

- an invisible barrier caused by discrimination that prevents women from rising to the highest levels of an organization—including corporations, governments, academic institutions, and religious organizations

- Title IX

- the section of the U.S. Education Amendments of 1972 that prohibits discrimination in education on the basis of sex

- Mary Beth Norton. 1980. Liberty’s Daughters: The Revolutionary Experience of American Women, 1750–1800. New York: Little, Brown, and Company, 46. ↵

- Ibid., 47. ↵

- Jan Ellen Lewis. 2011. “Rethinking Women’s Suffrage in New Jersey, 1776–1807,” Rutgers Law Review 63, No. 3, http://www.rutgerslawreview.com/wp-content/uploads/archive/vol63/Issue3/Lewis.pdf. ↵

- Keyssar, 174. ↵

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton. 1993. Eighty Years and More: Reminiscences, 1815–1897. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 148. ↵

- Elizabeth Cady Stanton et al. 1887. History of Woman Suffrage, vol. 1. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 73. ↵

- Jean H. Baker. 2005. Sisters: The Lives of America’s Suffragists. New York: Hill and Wang, 109. ↵

- Angelina Grimke. October 2, 1837. “Letter XII Human Rights Not Founded on Sex.” In Letters to Catherine E. Beecher: In Reply to an Essay on Slavery and Abolitionism. Boston: Knapp, 114–121. ↵

- Keyssar, 178. ↵

- Keyssar, 184. ↵

- Keyssar, 175, 186–187. ↵

- Keyssar, 214. ↵

- “Alice Paul,” https://www.nwhm.org/education-resources/biography/biographies/alice-paul/ (April 10, 2016). ↵

- Deborah Rhode. 2009. Justice and Gender: Sex Discrimination and the Law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 66–67. ↵

- Mark Hugo Lopez and Ana Gonzalez-Barrera. 6 March 2014. “Women’s College Enrollment Gains Leave Men Behind,” http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/03/06/womens-college-enrollment-gains-leave-men-behind/; Allie Bidwell, “Women More Likely to Graduate College, but Still Earn Less Than Men,” U.S. News & World Report, 31 October 2014. ↵

- “A Current Glance at Women in the Law–July 2014,” American Bar Association, July 2014; “Medical School Applicants, Enrollment Reach All-Time Highs,” Association of American Medical Colleges, October 24, 2013. ↵

- Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973). ↵

- “Pay Equity and Discrimination,” http://www.iwpr.org/initiatives/pay-equity-and-discrimination (April 10, 2016). ↵

- Gretchen Livingston. 2 July 2013. “The Rise of Single Fathers,” http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/07/02/the-rise-of-single-fathers/. ↵

- “Poverty in the U.S.: A Snapshot,” National Center for Law and Economic Justice, http://www.nclej.org/poverty-in-the-us.php. ↵

- “Current Numbers,” http://www.cawp.rutgers.edu/current-numbers (April 10, 2016). ↵

- “Statistics,” http://www.ncadv.org/learn/statistics [April 10, 2016]; “Statistics About Sexual Violence,” http://www.nsvrc.org/sites/default/files/publications_nsvrc_factsheet_media-packet_statistics-about-sexual-violence_0.pdf (April 10, 2016). ↵

- Heather D. Boonstra and Elizabeth Nash. 2014. “A Surge of State Abortion Restrictions Puts Providers–and the Women They Serve–in the Crosshairs,” Guttmacher Policy Review 17, No. 1, https://www.guttmacher.org/about/gpr/2014/03/surge-state-abortion-restrictions-puts-providers-and-women-they-serve-crosshairs. ↵

- Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, 579 U.S. ___ (2016). ↵

- Heather D. Boonstra. 2013. “Insurance Coverage of Abortion: Beyond the Exceptions for Life Endangerment, Rape and Incest,” Guttmacher Policy Review 16, No. 3, https://www.guttmacher.org/about/gpr/2013/09/insurance-coverage-abortion-beyond-exceptions-life-endangerment-rape-and-incest. ↵

- “Garbage Man Salary (United States),” http://www.payscale.com/research/US/Job=Garbage_Man/Hourly_Rate (April 10, 2016). ↵

- “Child Care/Day Care Worker Salary (United States),” http://www.payscale.com/research/US/Job=Child_Care_%2F_Day_Care_Worker/Hourly_Rate (April 10, 2016). ↵