Chapter 12: The Presidency

Presidential Governance: Direct Presidential Action

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the power presidents have to effect change without congressional cooperation

- Analyze how different circumstances influence the way presidents use unilateral authority

- Explain how presidents persuade others in the political system to support their initiatives

- Describe how historians and political scientists evaluate the effectiveness of a presidency

A president’s powers can be divided into two categories: direct actions the chief executive can take by employing the formal institutional powers of the office and informal powers of persuasion and negotiation essential to working with the legislative branch. When a president governs alone through direct action, it may break a policy deadlock or establish new grounds for action, but it may also spark opposition that might have been handled differently through negotiation and discussion. Moreover, such decisions are subject to court challenge, legislative reversal, or revocation by a successor. What may seem to be a sign of strength is often more properly understood as independent action undertaken in the wake of a failure to achieve a solution through the legislative process, or an admission that such an effort would prove futile. When it comes to national security, international negotiations, or war, the president has many more opportunities to act directly and in some cases must do so when circumstances require quick and decisive action.

DOMESTIC POLICY

The president may not be able to appoint key members of his or her administration without Senate confirmation, but he or she can demand the resignation or removal of cabinet officers, high-ranking appointees (such as ambassadors), and members of the presidential staff. During Reconstruction, Congress tried to curtail the president’s removal power with the Tenure of Office Act (1867), which required Senate concurrence to remove presidential nominees who took office upon Senate confirmation. Andrew Johnson’s violation of that legislation provided the grounds for his impeachment in 1868. Subsequent presidents secured modifications of the legislation before the Supreme Court ruled in 1926 that the Senate had no right to impair the president’s removal power.[1]

In the case of Senate failure to approve presidential nominations, the president is empowered to issue recess appointments (made while the Senate is in recess) that continue in force until the end of the next session of the Senate (unless the Senate confirms the nominee).

The president also exercises the power of pardon without conditions. Once used fairly sparingly—apart from Andrew Johnson’s wholesale pardons of former Confederates during the Reconstruction period—the pardon power has become more visible in recent decades. President Harry S. Truman issued over two thousand pardons and commutations, more than any other post–World War II president.[2]

President Gerald Ford has the unenviable reputation of being the only president to pardon another president (his predecessor Richard Nixon, who resigned after the Watergate scandal) ((Figure)). While not as generous as Truman, President Jimmy Carter also issued a great number of pardons, including several for draft dodging during the Vietnam War. President Reagan was reluctant to use the pardon as much, as was President George H. W. Bush. President Clinton pardoned few people for much of his presidency, but did make several last-minute pardons, which led to some controversy. To date, Barack Obama has seldom used his power to pardon.[3]

Figure 1. In 1974, President Ford became the first and still the only president to pardon a previous president (Richard Nixon). Here he is speaking before the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Criminal Justice meeting explaining his reasons. While the pardon was unpopular with many and may have cost Ford the election two years later, his constitutional power to issue it is indisputable. (credit: modification of work by the Library of Congress)

Presidents may choose to issue executive orders or proclamations to achieve policy goals. Usually, executive orders direct government agencies to pursue a certain course in the absence of congressional action. A more subtle version pioneered by recent presidents is the executive memorandum, which tends to attract less attention. Many of the most famous executive orders have come in times of war or invoke the president’s authority as commander-in-chief, including Franklin Roosevelt’s order permitting the internment of Japanese Americans in 1942 and Harry Truman’s directive desegregating the armed forces (1948). The most famous presidential proclamation was Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation (1863), which declared slaves in areas under Confederate control to be free (with a few exceptions).

Executive orders are subject to court rulings or changes in policy enacted by Congress. During the Korean War, the Supreme Court revoked Truman’s order seizing the steel industry.[4]

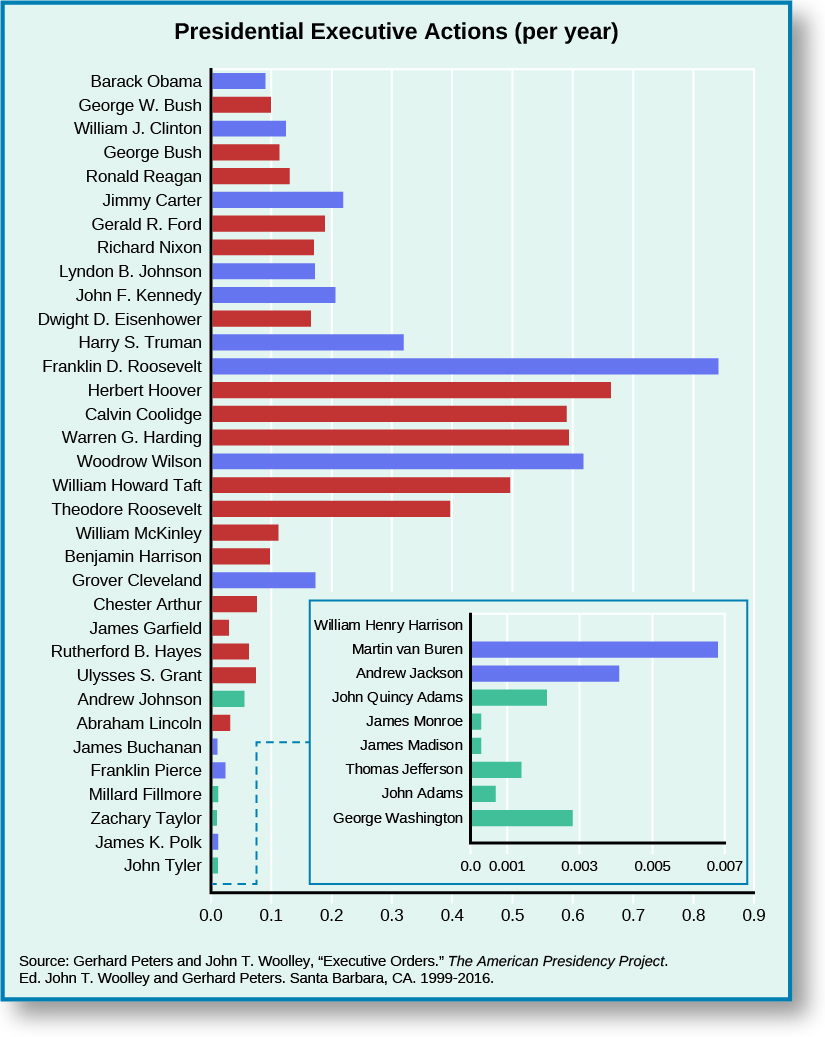

These orders are also subject to reversal by presidents who come after, and recent presidents have wasted little time reversing the orders of their predecessors in cases of disagreement. Sustained executive orders, which are those not overturned in courts, typically have some prior authority from Congress that legitimizes them. When there is no prior authority, it is much more likely that an executive order will be overturned by a later president. For this reason, this tool has become less common in recent decades ((Figure)).

|

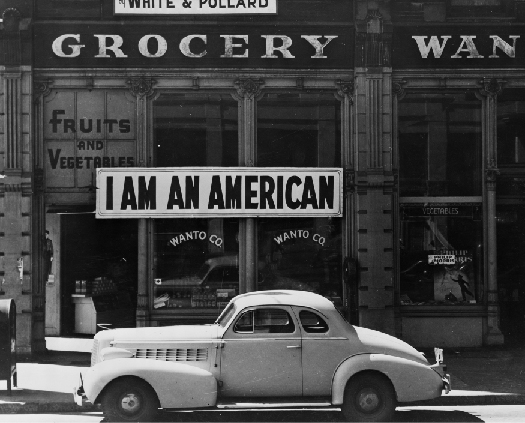

Executive Order 9066 Following the devastating Japanese attacks on the U.S. Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor in 1941, many in the United States feared that Japanese Americans on the West Coast had the potential and inclination to form a fifth column (a hostile group working from the inside) for the purpose of aiding a Japanese invasion. These fears mingled with existing anti-Japanese sentiment across the country and created a paranoia that washed over the West Coast like a large wave. In an attempt to calm fears and prevent any real fifth-column actions, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the removal of people from military areas as necessary. When the military dubbed the entire West Coast a military area, it effectively allowed for the removal of more than 110,000 Japanese Americans from their homes. These people, many of them U.S. citizens, were moved to relocation centers in the interior of the country. They lived in the camps there for two and a half years ((Figure)).[5]  Figure 3. This sign appeared outside a store in Oakland, California, owned by a Japanese American after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941. After the president’s executive order, the store was closed and the owner evacuated to an internment camp for the duration of the war. (credit: the Library of Congress) The overwhelming majority of Japanese Americans felt shamed by the actions of the Japanese empire and willingly went along with the policy in an attempt to demonstrate their loyalty to the United States. But at least one Japanese American refused to go along. His name was Fred Korematsu, and he decided to go into hiding in California rather than be taken to the internment camps with his family. He was soon discovered, turned over to the military, and sent to the internment camp in Utah that held his family. But his challenge to the internment system and the president’s executive order continued. In 1944, Korematsu’s case was heard by the Supreme Court. In a 6–3 decision, the Court ruled against him, arguing that the administration had the constitutional power to sign the order because of the need to protect U.S. interests against the threat of espionage.[6] Forty-four years after this decision, President Reagan issued an official apology for the internment and provided some compensation to the survivors. In 2011, the Justice Department went a step further by filing a notice officially recognizing that the solicitor general of the United States acted in error by arguing to uphold the executive order. (The solicitor general is the official who argues cases for the U.S. government before the Supreme Court.) However, despite these actions, in 2014, the late Supreme Court justice Antonin Scalia was documented as saying that while he believed the decision was wrong, it could occur again.[7] What do the Korematsu case and the internment of over 100,000 Japanese Americans suggest about the extent of the president’s war powers? What does this episode in U.S. history suggest about the weaknesses of constitutional checks on executive power during times of war? |

Finally, presidents have also used the line-item veto and signing statements to alter or influence the application of the laws they sign. A line-item veto is a type of veto that keeps the majority of a spending bill unaltered but nullifies certain lines of spending within it. While a number of states allow their governors the line-item veto (discussed in the chapter on state and local government), the president acquired this power only in 1996 after Congress passed a law permitting it. President Clinton used the tool sparingly. However, those entities that stood to receive the federal funding he lined out brought suit. Two such groups were the City of New York and the Snake River Potato Growers in Idaho.[8]

The Supreme Court heard their claims together and just sixteen months later declared unconstitutional the act that permitted the line-item veto.[9]

Since then, presidents have asked Congress to draft a line-item veto law that would be constitutional, although none have made it to the president’s desk.

On the other hand, signing statements are statements issued by a president when agreeing to legislation that indicate how the chief executive will interpret and enforce the legislation in question. Signing statements are less powerful than vetoes, though congressional opponents have complained that they derail legislative intent. Signing statements have been used by presidents since at least James Monroe, but they became far more common in this century.

NATIONAL SECURITY, FOREIGN POLICY, AND WAR

Presidents are more likely to justify the use of executive orders in cases of national security or as part of their war powers. In addition to mandating emancipation and the internment of Japanese Americans, presidents have issued orders to protect the homeland from internal threats. Most notably, Lincoln ordered the suspension of the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus in 1861 and 1862 before seeking congressional legislation to undertake such an act. Presidents hire and fire military commanders; they also use their power as commander-in-chief to aggressively deploy U.S. military force. Congress rarely has taken the lead over the course of history, with the War of 1812 being the lone exception. Pearl Harbor was a salient case where Congress did make a clear and formal declaration when asked by FDR. However, since World War II, it has been the president and not Congress who has taken the lead in engaging the United States in military action outside the nation’s boundaries, most notably in Korea, Vietnam, and the Persian Gulf ((Figure)).

Figure 4. By landing on an aircraft carrier and wearing a flight suit to announce the end of major combat operations in Iraq in 2003, President George W. Bush was carefully emphasizing his presidential power as commander-in-chief. (credit: Tyler J. Clements)

Presidents also issue executive agreements with foreign powers. Executive agreements are formal agreements negotiated between two countries but not ratified by a legislature as a treaty must be. As such, they are not treaties under U.S. law, which require two-thirds of the Senate for ratification. Treaties, presidents have found, are particularly difficult to get ratified. And with the fast pace and complex demands of modern foreign policy, concluding treaties with countries can be a tiresome and burdensome chore. That said, some executive agreements do require some legislative approval, such as those that commit the United States to make payments and thus are restrained by the congressional power of the purse. But for the most part, executive agreements signed by the president require no congressional action and are considered enforceable as long as the provisions of the executive agreement do not conflict with current domestic law.

THE POWER OF PERSUASION

The framers of the Constitution, concerned about the excesses of British monarchial power, made sure to design the presidency within a network of checks and balances controlled by the other branches of the federal government. Such checks and balances encourage consultation, cooperation, and compromise in policymaking. This is most evident at home, where the Constitution makes it difficult for either Congress or the chief executive to prevail unilaterally, at least when it comes to constructing policy. Although much is made of political stalemate and obstructionism in national political deliberations today, the framers did not want to make it too easy to get things done without a great deal of support for such initiatives.

It is left to the president to employ a strategy of negotiation, persuasion, and compromise in order to secure policy achievements in cooperation with Congress. In 1960, political scientist Richard Neustadt put forward the thesis that presidential power is the power to persuade, a process that takes many forms and is expressed in various ways.[10]

Yet the successful employment of this technique can lead to significant and durable successes. For example, legislative achievements tend to be of greater duration because they are more difficult to overturn or replace, as the case of health care reform under President Barack Obama suggests. Obamacare has faced court cases and repeated (if largely symbolic) attempts to gut it in Congress. Overturning it will take a new president who opposes it, together with a Congress that can pass the dissolving legislation.

In some cases, cooperation is essential, as when the president nominates and the Senate confirms persons to fill vacancies on the Supreme Court, an increasingly contentious area of friction between branches. While Congress cannot populate the Court on its own, it can frustrate the president’s efforts to do so. Presidents who seek to prevail through persuasion, according to Neustadt, target Congress, members of their own party, the public, the bureaucracy, and, when appropriate, the international community and foreign leaders. Of these audiences, perhaps the most obvious and challenging is Congress.[11]

Much depends on the balance of power within Congress: Should the opposition party hold control of both houses, it will be difficult indeed for the president to realize his or her objectives, especially if the opposition is intent on frustrating all initiatives. However, even control of both houses by the president’s own party is no guarantee of success or even of productive policymaking. For example, neither Bill Clinton nor Barack Obama achieved all they desired despite having favorable conditions for the first two years of their presidencies. In times of divided government (when one party controls the presidency and the other controls one or both chambers of Congress), it is up to the president to cut deals and make compromises that will attract support from at least some members of the opposition party without excessively alienating members of his or her own party. Both Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton proved effective in dealing with divided government—indeed, Clinton scored more successes with Republicans in control of Congress than he did with Democrats in charge.

It is more difficult to persuade members of the president’s own party or the public to support a president’s policy without risking the dangers inherent in going public. There is precious little opportunity for private persuasion while also going public in such instances, at least directly. The way the president and his or her staff handle media coverage of the administration may afford some opportunities for indirect persuasion of these groups. It is not easy to persuade the federal bureaucracy to do the president’s bidding unless the chief executive has made careful appointments. When it comes to diplomacy, the president must relay some messages privately while offering incentives, both positive and negative, in order to elicit desired responses, although at times, people heed only the threat of force and coercion.

While presidents may choose to go public in an attempt to put pressure on other groups to cooperate, most of the time they “stay private” as they attempt to make deals and reach agreements out of the public eye. The tools of negotiation have changed over time. Once chief executives played patronage politics, rewarding friends while attacking and punishing critics as they built coalitions of support. But the advent of civil service reform in the 1880s systematically deprived presidents of that option and reduced its scope and effectiveness. Although the president may call upon various agencies for assistance in lobbying for proposals, such as the Office of Legislative Liaison with Congress, it is often left to the chief executive to offer incentives and rewards. Some of these are symbolic, like private meetings in the White House or an appearance on the campaign trail. The president must also find common ground and make compromises acceptable to all parties, thus enabling everyone to claim they secured something they wanted.

Complicating Neustadt’s model, however, is that many of the ways he claimed presidents could shape favorable outcomes require going public, which as we have seen can produce mixed results. Political scientist Fred Greenstein, on the other hand, touted the advantages of a “hidden hand presidency,” in which the chief executive did most of the work behind the scenes, wielding both the carrot and the stick.

Greenstein singled out President Dwight Eisenhower as particularly skillful in such endeavors.

OPPORTUNITY AND LEGACY

What often shapes a president’s performance, reputation, and ultimately legacy depends on circumstances that are largely out of his or her control. Did the president prevail in a landslide or was it a closely contested election? Did he or she come to office as the result of death, assassination, or resignation? How much support does the president’s party enjoy, and is that support reflected in the composition of both houses of Congress, just one, or neither? Will the president face a Congress ready to embrace proposals or poised to oppose them? Whatever a president’s ambitions, it will be hard to realize them in the face of a hostile or divided Congress, and the options to exercise independent leadership are greater in times of crisis and war than when looking at domestic concerns alone.

Then there is what political scientist Stephen Skowronek calls “political time.”[12]

Some presidents take office at times of great stability with few concerns. Unless there are radical or unexpected changes, a president’s options are limited, especially if voters hoped for a simple continuation of what had come before. Other presidents take office at a time of crisis or when the electorate is looking for significant changes. Then there is both pressure and opportunity for responding to those challenges. Some presidents, notably Theodore Roosevelt, openly bemoaned the lack of any such crisis, which Roosevelt deemed essential for him to achieve greatness as a president.

People in the United States claim they want a strong president. What does that mean? At times, scholars point to presidential independence, even defiance, as evidence of strong leadership. Thus, vigorous use of the veto power in key situations can cause observers to judge a president as strong and independent, although far from effective in shaping constructive policies. Nor is such defiance and confrontation always evidence of presidential leadership skill or greatness, as the case of Andrew Johnson should remind us. When is effectiveness a sign of strength, and when are we confusing being headstrong with being strong? Sometimes, historians and political scientists see cooperation with Congress as evidence of weakness, as in the case of Ulysses S. Grant, who was far more effective in garnering support for administration initiatives than scholars have given him credit for.

These questions overlap with those concerning political time and circumstance. While domestic policymaking requires far more give-and-take and a fair share of cajoling and collaboration, national emergencies and war offer presidents far more opportunity to act vigorously and at times independently. This phenomenon often produces the rally around the flag effect, in which presidential popularity spikes during international crises. A president must always be aware that politics, according to Otto von Bismarck, is the art of the possible, even as it is his or her duty to increase what might be possible by persuading both members of Congress and the general public of what needs to be done.

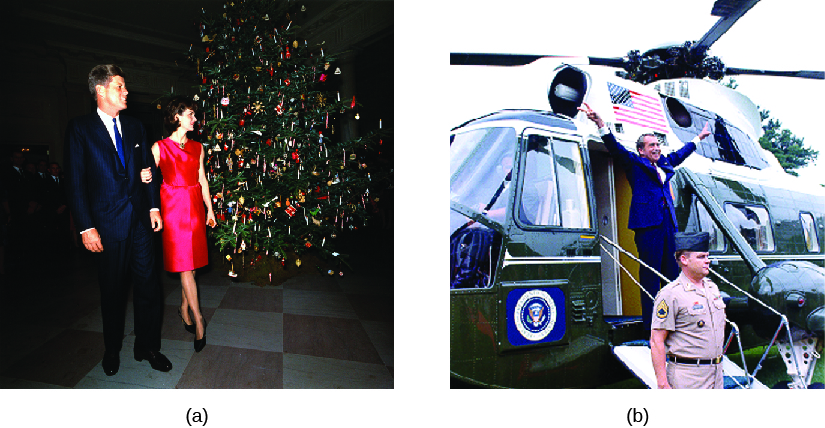

Finally, presidents often leave a legacy that lasts far beyond their time in office ((Figure)). Sometimes, this is due to the long-term implications of policy decisions. Critical to the notion of legacy is the shaping of the Supreme Court as well as other federal judges. Long after John Adams left the White House in 1801, his appointment of John Marshall as chief justice shaped American jurisprudence for over three decades. No wonder confirmation hearings have grown more contentious in the cases of highly visible nominees. Other legacies are more difficult to define, although they suggest that, at times, presidents cast a long shadow over their successors. It was a tough act to follow George Washington, and in death, Abraham Lincoln’s presidential stature grew to extreme heights. Theodore and Franklin D. Roosevelt offered models of vigorous executive leadership, while the image and style of John F. Kennedy and Ronald Reagan influenced and at times haunted or frustrated successors. Nor is this impact limited to chief executives deemed successful: Lyndon Johnson’s Vietnam and Richard Nixon’s Watergate offered cautionary tales of presidential power gone wrong, leaving behind legacies that include terms like Vietnam syndrome and the tendency to add the suffix “-gate” to scandals and controversies.

Figure 5. The youth and glamour that John F. Kennedy and first lady Jacqueline brought to the White House in the early 1960s (a) helped give rise to the legend of “one brief shining moment that was Camelot” after Kennedy’s presidency was cut short by his assassination on November 22, 1963. Despite a tainted legacy, President Richard Nixon gives his trademark “V for Victory” sign as he leaves the White House on August 9, 1974 (b), after resigning in the wake of the Watergate scandal.

Summary

While the power of the presidency is typically checked by the other two branches of government, presidents have the unencumbered power to pardon those convicted of federal crimes and to issue executive orders, which don’t require congressional approval but lack the permanence of laws passed by Congress. In matters concerning foreign policy, presidents have at their disposal the executive agreement, which is a much-easier way for two countries to come to terms than a treaty that requires Senate ratification but is also much narrower in scope.

Presidents use various means to attempt to drive public opinion and effect political change. But history has shown that they are limited in their ability to drive public opinion. Favorable conditions can help a president move policies forward. These conditions include party control of Congress and the arrival of crises such as war or economic decline. But as some presidencies have shown, even the most favorable conditions don’t guarantee success.

| NOTE: The activities below will not be counted towards your final grade for this class. They are strictly here to help you check your knowledge in preparation for class assignments and future dialogue. Best of luck! |

Suggested ReadingEdwards, George C. 2016. Predicting the Presidency: The Potential of Persuasive Leadership. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Edwards, George C. and Stephen J. Wayne. 2003. Presidential Leadership: Politics and Policy Making. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. Erickson, Robert S. and Christopher Wlezien. 2012. The Timeline of Presidential Elections: How Campaigns Do (and Do Not) Matter. Chicago: Chicago University Press. Greenstein, Fred I. 1982. The Hidden-Hand Presidency: Eisenhower as Leader. New York: Basic Books. Kernell, Samuel. 1986. Going Public: New Strategies of Presidential Leadership. Washington, DC: CQ Press. McGinnis, Joe. 1988. The Selling of the President. New York: Penguin Books. Nelson, Michael. 1984. The Presidency and the Political System. Washington, DC: CQ Press. Neustadt, Richard E. 1990. Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents: The Politics of Leadership from Roosevelt to Reagan. New York: Free Press. Pfiffner, James P. 1994. The Modern Presidency. New York: St. Martin’s Press. Pika, Joseph August, John Anthony Maltese, Norman C. Thomas, and Norman C. Thomas. 2002. The Politics of the Presidency. Washington, DC: CQ Press. Porter, Roger B. 1980. Presidential Decision Making: The Economic Policy Board. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Skowronek, Stephen. 2011. Presidential Leadership in Political Time: Reprise and Reappraisal. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. |

Glossary

- line-item veto

- a power created through law in 1996 and overturned by the Supreme Court in 1998 that allowed the president to veto specific aspects of bills passed by Congress while signing into law what remained

- rally around the flag effect

- a spike in presidential popularity during international crises

- signing statement

- a statement a president issues with the intent to influence the way a specific bill the president signs should be enforced

- Myers v. United States, 272 U.S. 52 (1925). ↵

- “Bush Issues Pardons, but to a Relative Few,” New York Times, 22 December 2006, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/22/washington/22pardon.html. ↵

- U.S. Department of Justice. “Clemency Statistics.” https://www.justice.gov/pardon/clemency-statistics (May 1, 2016). ↵

- Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952). ↵

- Julie Des Jardins, “From Citizen to Enemy: The Tragedy of Japanese Internment,” http://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/world-war-ii/essays/from-citizen-enemy-tragedy-japanese-internment (May 1, 2016). ↵

- Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944). ↵

- Ilya Somin, “Justice Scalia on Kelo and Korematsu,” Washington Post, 8 February 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/volokh-conspiracy/wp/2014/02/08/justice-scalia-on-kelo-and-korematsu/. ↵

- Glen S. Krutz. 2001. Hitching a Ride: Omnibus Legislating in the U.S. Congress. Columbus, OH: Ohio State University Press. ↵

- Clinton v. City of New York, 524 U.S. 417 (1998). ↵

- Richard E. Neustadt. 1960. Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents New York: Wiley. ↵

- Read “Power Lessons for Obama” at this website to learn more about applying Richard Neustadt’s framework to the leaders of today. ↵

- Stephen Skowronek. 2011. Presidential Leadership in Political Time: Reprise and Reappraisal. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ↵