Chapter 10: Interest Groups and Lobbying

Interest Groups as Political Participation

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Analyze how interest groups provide a means for political participation

- Discuss recent changes to interest groups and the way they operate in the United States

- Explain why lower socioeconomic status citizens are not well represented by interest groups

- Identify the barriers to interest group participation in the United States

Interest groups offer individuals an important avenue for political participation. Tea Party protests, for instance, gave individuals all over the country the opportunity to voice their opposition to government actions and control. Likewise, the Occupy Wall Street movement also gave a voice to those individuals frustrated with economic inequality and the influence of large corporations on the public sector. Individually, the protestors would likely have received little notice, but by joining with others, they drew substantial attention in the media and from lawmakers ((Figure)). While the Tea Party movement might not meet the definition of interest groups presented earlier, its aims have been promoted by established interest groups. Other opportunities for participation that interest groups offer or encourage include voting, campaigning, contacting lawmakers, and informing the public about causes.

Figure 1. In 2011, an Occupy Wall Street protestor highlights that the concerns of individual citizens are not always heard by those in the seats of power. (credit: Timothy Krause)

GROUP PARTICIPATION AS CIVIC ENGAGEMENT

Joining interest groups can help facilitate civic engagement, which allows people to feel more connected to the political and social community. Some interest groups develop as grassroots movements, which often begin from the bottom up among a small number of people at the local level. Interest groups can amplify the voices of such individuals through proper organization and allow them to participate in ways that would be less effective or even impossible alone or in small numbers. The Tea Party is an example of a so-called astroturf movement, because it is not, strictly speaking, a grassroots movement. Many trace the party’s origins to groups that champion the interests of the wealthy such as Americans for Prosperity and Citizens for a Sound Economy. Although many ordinary citizens support the Tea Party because of its opposition to tax increases, it attracts a great deal of support from elite and wealthy sponsors, some of whom are active in lobbying. The FreedomWorks political action committee (PAC), for example, is a conservative advocacy group that has supported the Tea Party movement. FreedomWorks is an offshoot of the interest group Citizens for a Sound Economy, which was founded by billionaire industrialists David H. and Charles G. Koch in 1984.

According to political scientists Jeffrey Berry and Clyde Wilcox, interest groups provide a means of representing people and serve as a link between them and government.[1]

Interest groups also allow people to actively work on an issue in an effort to influence public policy. Another function of interest groups is to help educate the public. Someone concerned about the environment may not need to know what an acceptable level of sulfur dioxide is in the air, but by joining an environmental interest group, he or she can remain informed when air quality is poor or threatened by legislative action. A number of education-related interests have been very active following cuts to education spending in many states, including North Carolina, Mississippi, and Wisconsin, to name a few.

Interest groups also help frame issues, usually in a way that best benefits their cause. Abortion rights advocates often use the term “pro-choice” to frame abortion as an individual’s private choice to be made free of government interference, while an anti-abortion group might use the term “pro-life” to frame its position as protecting the life of the unborn. “Pro-life” groups often label their opponents as “pro-abortion,” rather than “pro-choice,” a distinction that can affect the way the public perceives the issue. Similarly, scientists and others who believe that human activity has had a negative effect on the earth’s temperature and weather patterns attribute such phenomena as the increasing frequency and severity of storms to “climate change.” Industrialists and their supporters refer to alterations in the earth’s climate as “global warming.” Those who dispute that such a change is taking place can thus point to blizzards and low temperatures as evidence that the earth is not becoming warmer.

Interest groups also try to get issues on the government agenda and to monitor a variety of government programs. Following the passage of the ACA, numerous interest groups have been monitoring the implementation of the law, hoping to use successes and failures to justify their positions for and against the legislation. Those opposed have utilized the court system to try to alter or eliminate the law, or have lobbied executive agencies or departments that have a role in the law’s implementation. Similarly, teachers’ unions, parent-teacher organizations, and other education-related interests have monitored implementation of the No Child Left Behind Act promoted and signed into law by President George W. Bush.

|

Interest Groups as a Response to Riots The LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) movement owes a great deal to the gay rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s, and in particular to the 1969 riots at the Stonewall Inn in New York’s Greenwich Village. These were a series of violent responses to a police raid on the bar, a popular gathering place for members of the LGBT community. The riots culminated in a number of arrests but also raised awareness of the struggles faced by members of the gay and lesbian community.[2] The Stonewall Inn has recently been granted landmark status by New York City’s Landmarks Preservation Commission ((Figure)).  Figure 2. The Stonewall Inn in New York City’s Greenwich Village was the site of arrests and riots in 1969 that, like the building itself, became an important landmark in the LGBT movement. (credit: Steven Damron) The Castro district in San Francisco, California, was also home to a significant LGBT community during the same time period. In 1978, the community was shocked when Harvey Milk, a gay local activist and sitting member of San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors, was assassinated by a former city supervisor due to political differences.[3] This resulted in protests in San Francisco and other cities across the country and the mobilization of interests concerned about gay and lesbian rights. Today, advocacy interest organizations like Human Rights Watch and the Human Rights Council are at the forefront in supporting members of the LGBT community and popularizing a number of relevant issues. They played an active role in the effort to legalize same-sex marriage in individual states and later nationwide. Now that same-sex marriage is legal, these organizations and others are dealing with issues related to continuing discrimination against members of this community. One current debate centers around whether an individual’s religious freedom allows him or her to deny services to members of the LGBT community. What do you feel are lingering issues for the LGBT community? What approaches could you take to help increase attention and support for gay and lesbian rights? Do you think someone’s religious beliefs should allow them the freedom to discriminate against members of the LGBT community? Why or why not? |

TRENDS IN PUBLIC INTEREST GROUP FORMATION AND ACTIVITY

A number of changes in interest groups have taken place over the last three or four decades in the United States. The most significant change is the tremendous increase in both the number and type of groups.[4]

Political scientists often examine the diversity of registered groups, in part to determine how well they reflect the variety of interests in society. Some areas may be dominated by certain industries, while others may reflect a multitude of interests. Some interests appear to have increased at greater rates than others. For example, the number of institutions and corporate interests has increased both in Washington and in the states. Telecommunication companies like Verizon and AT&T will lobby Congress for laws beneficial to their businesses, but they also target the states because state legislatures make laws that can benefit or harm their activities. There has also been an increase in the number of public interest groups that represent the public as opposed to economic interests. U.S. PIRG is a public interest group that represents the public on issues including public health, the environment, and consumer protection.[5]

|

Public Interest Research Groups Public interest research groups (PIRGs) have increased in recent years, and many now exist nationally and at the state level. PIRGs represent the public in a multitude of issue areas, ranging from consumer protection to the environment, and like other interests, they provide opportunities for people to make a difference in the political process. PIRGs try to promote the common or public good, and most issues they favor affect many or even all citizens. Student PIRGs focus on issues that are important to students, including tuition costs, textbook costs, new voter registration, sustainable universities, and homelessness. Consider the cost of a college education. You may want to research how education costs have increased over time. Are cost increases similar across universities and colleges? Are they similar across states? What might explain similarities and differences in tuition costs? What solutions might help address the rising costs of higher education? How can you get involved in the drive for affordable college education? Consider why students might become engaged in it and why they might not do so. A number of countries have made tuition free or nearly free.[6] Is this feasible or desirable in the United States? Why or why not? |

What are the reasons for the increase in the number of interest groups? In some cases, it simply reflects new interests in society. Forty years ago, stem cell research was not an issue on the government agenda, but as science and technology advanced, its techniques and possibilities became known to the media and the public, and a number of interests began lobbying for and against this type of research. Medical research firms and medical associations will lobby in favor of greater spending and increased research on stem cell research, while some religious organizations and anti-abortion groups will oppose it. As societal attitudes change and new issues develop, and as the public becomes aware of them, we can expect to see the rise of interests addressing them.

The devolution of power also explains some of the increase in the number and type of interests, at least at the state level. As power and responsibility shifted to state governments in the 1980s, the states began to handle responsibilities that had been under the jurisdiction of the federal government. A number of federal welfare programs, for example, are generally administered at the state level. This means interests might be better served targeting their lobbying efforts in Albany, Raleigh, Austin, or Sacramento, rather than only in Washington, DC. As the states have become more active in more policy areas, they have become prime targets for interests wanting to influence policy in their favor.[7]

We have also seen increased specialization by some interests and even fragmentation of existing interests. While the American Medical Association may take a stand on stem cell research, the issue is not critical to the everyday activities of many of its members. On the other hand, stem cell research is highly salient to members of the American Neurological Association, an interest organization that represents academic neurologists and neuroscientists. Accordingly, different interests represent the more specialized needs of different specialties within the medical community, but fragmentation can occur when a large interest like this has diverging needs. Such was also the case when several unions split from the AFL-CIO (American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations), the nation’s largest federation of unions, in 2005.[8]

Improved technology and the development of social media have made it easier for smaller groups to form and to attract and communicate with members. The use of the Internet to raise money has also made it possible for even small groups to receive funding.

None of this suggests that an unlimited number of interests can exist in society. The size of the economy has a bearing on the number of interests, but only up to a certain point, after which the number increases at a declining rate. As we will see below, the limit on the number of interests depends on the available resources and levels of competition.

Over the last few decades, we have also witnessed an increase in professionalization in lobbying and in the sophistication of lobbying techniques. This was not always the case, because lobbying was not considered a serious profession in the mid-twentieth century. Over the past three decades, there has been an increase in the number of contract lobbying firms. These firms are often effective because they bring significant resources to the table, their lobbyists are knowledgeable about the issues on which they lobby, and they may have existing relationships with lawmakers. In fact, relationships between lobbyists and legislators are often ongoing, and these are critical if lobbyists want access to lawmakers. However, not every interest can afford to hire high-priced contract lobbyists to represent it. As (Figure) suggests, a great deal of money is spent on lobbying activities.

| Top Lobbying Firms in 2014 | |

|---|---|

| Lobbying Firm | Total Lobbying Annual Income |

| Akin, Gump et al. | $35,550,000 |

| Squire Patton Boggs | $31,540,000 |

| Podesta Group | $25,070,000 |

| Brownstein, Hyatt et al. | $23,400,000 |

| Van Scoyoc Assoc. | $21,420,000 |

| Holland & Knight | $19,250,000 |

| Capitol Counsel | $17,930,000 |

| K&L Gates | $17,420,000 |

| Williams & Jensen | $16,430,000 |

| BGR Group | $15,470,000 |

| Peck Madigan Jones | $13,395,000 |

| Cornerstone Government Affairs | $13,380,000 |

| Ernst & Young | $12,440,000 |

| Hogan Lovells | $12,410,000 |

| Capitol Tax Partners | $12,390,000 |

| Cassidy & Assoc. | $12,090,000 |

| Fierce, Isakowitz & Blalock | $11,970,000 |

| Covington & Burling | $11,537,000 |

| Mehlman, Castagnetti et al. | $11,180,000 |

| Alpine Group | $10,950,00 |

We have also seen greater limits on inside lobbying activities. In the past, many lobbyists were described as “good ol’ boys” who often provided gifts or other favors in exchange for political access or other considerations. Today, restrictions limit the types of gifts and benefits lobbyists can bestow on lawmakers. There are certainly fewer “good ol’ boy” lobbyists, and many lobbyists are now full-time professionals. The regulation of lobbying is addressed in greater detail below.

HOW REPRESENTATIVE IS THE INTEREST GROUP SYSTEM?

Participation in the United States has never been equal; wealth and education, components of socioeconomic status, are strong predictors of political engagement.[9]

We already discussed how wealth can help overcome collective action problems, but lack of wealth also serves as a barrier to participation more generally. These types of barriers pose challenges, making it less likely for some groups than others to participate.[10]

Some institutions, including large corporations, are more likely to participate in the political process than others, simply because they have tremendous resources. And with these resources, they can write a check to a political campaign or hire a lobbyist to represent their organization. Writing a check and hiring a lobbyist are unlikely options for a disadvantaged group ((Figure)).

Figure 3. A protestor at an Occupy Times Square rally in October 2011. (credit: Geoff Stearns)

Individually, the poor may not have the same opportunities to join groups.[11] They may work two jobs to make ends meet and lack the free time necessary to participate in politics. Further, there are often financial barriers to participation. For someone who punches a time-clock, spending time with political groups may be costly and paying dues may be a hardship. Certainly, the poor are unable to hire expensive lobbying firms to represent them. Structural barriers like voter identification laws may also disproportionately affect people with low socioeconomic status, although the effects of these laws may not be fully understood for some time.

The poor may also have low levels of efficacy, which refers to the conviction that you can make a difference or that government cares about you and your views. People with low levels of efficacy are less likely to participate in politics, including voting and joining interest groups. Therefore, they are often underrepresented in the political arena.

Minorities may also participate less often than the majority population, although when we control for wealth and education levels, we see fewer differences in participation rates. Still, there is a bias in participation and representation, and this bias extends to interest groups as well. For example, when fast food workers across the United States went on strike to demand an increase in their wages, they could do little more than take to the streets bearing signs, like the protestors shown in (Figure). Their opponents, the owners of restaurant chains and others who pay their employees minimum wage, could hire groups such as the Employment Policies Institute, which paid for billboard ads in Times Square in New York City. The billboards implied that raising the minimum wage was an insult to people who worked hard and discouraged people from getting an education to better their lives.[12]

Figure 4. Unlike their opponents, these minimum-wage workers in Minnesota have limited ways to make their interests known to government. However, they were able to increase their political efficacy by joining fast food workers in a nationwide strike on April 15, 2015, to call for a $15 per hour minimum wage and improved working conditions. (credit: “Fibonacci Blue”/Flickr)

Finally, people do not often participate because they lack the political skill to do so or believe that it is impossible to influence government actions.[13] They might also lack interest or could be apathetic. Participation usually requires some knowledge of the political system, the candidates, or the issues. Younger people in particular are often cynical about government’s response to the needs of non-elites.

How do these observations translate into the way different interests are represented in the political system? Some pluralist scholars like David Truman suggest that people naturally join groups and that there will be a great deal of competition for access to decision-makers.[14]

Scholars who subscribe to this pluralist view assume this competition among diverse interests is good for democracy. Political theorist Robert Dahl argued that “all active and legitimate groups had the potential to make themselves heard.”[15] In many ways, this is an optimistic assessment of representation in the United States.

However, not all scholars accept the premise that mobilization is natural and that all groups have the potential for access to decision-makers. The elite critique suggests that certain interests, typically businesses and the wealthy, are advantaged and that policies more often reflect their wishes than anyone else’s. Political scientist E. E. Schattschneider noted that “the flaw in the pluralist heaven is that the heavenly chorus sings with a strong upperclass accent.”[16]

A number of scholars have suggested that businesses and other wealthy interests are often overrepresented before government, and that poorer interests are at a comparative disadvantage.[17] For example, as we’ve seen, wealthy corporate interests have the means to hire in-house lobbyists or high-priced contract lobbyists to represent them. They can also afford to make financial contributions to politicians, which at least may grant them access. The ability to overcome collective action problems is not equally distributed across groups; as Mancur Olson noted, small groups and those with economic advantages were better off in this regard.[18] Disadvantaged interests face many challenges including shortages of resources, time, and skills.

A study of almost eighteen hundred policy decisions made over a twenty-year period revealed that the interests of the wealthy have much greater influence on the government than those of average citizens. The approval or disapproval of proposed policy changes by average voters had relatively little effect on whether the changes took place. When wealthy voters disapproved of a particular policy, it almost never was enacted. When wealthy voters favored a particular policy, the odds of the policy proposal’s passing increased to more than 50 percent.[19]

Indeed, the preferences of those in the top 10 percent of the population in terms of income had an impact fifteen times greater than those of average income. In terms of the effect of interest groups on policy, Gilens and Page found that business interest groups had twice the influence of public interest groups.[20]

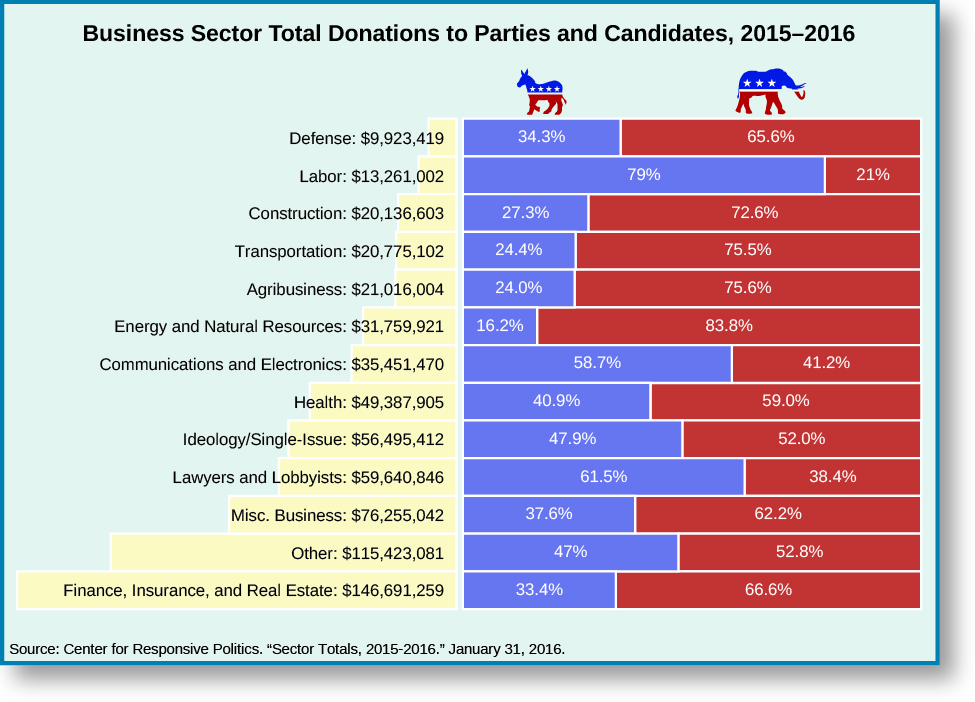

The (Figure) below shows contributions by interests from a variety of different sectors. We can draw a few notable observations from the table. First, large sums of money are spent by different interests. Second, many of these interests are business sectors, including the real estate sector, the insurance industry, businesses, and law firms.

Figure 5. The chart above shows the dollar amounts contributed from PACs, soft money (including directly from corporate and union treasuries), and individual donors to Democratic (blue) and Republican (red) federal candidates and political parties during the 2015–2016 election cycle, as reported to the Federal Election Commission.

Interest group politics are often characterized by whether the groups have access to decision-makers and can participate in the policy-making process. The iron triangle is a hypothetical arrangement among three elements (the corners of the triangle): an interest group, a congressional committee member or chair, and an agency within the bureaucracy.[21]

Each element has a symbiotic relationship with the other two, and it is difficult for those outside the triangle to break into it. The congressional committee members, including the chair, rely on the interest group for campaign contributions and policy information, while the interest group needs the committee to consider laws favorable to its view. The interest group and the committee need the agency to implement the law, while the agency needs the interest group for information and the committee for funding and autonomy in implementing the law.[22]

An alternate explanation of the arrangement of duties carried out in a given policy area by interest groups, legislators, and agency bureaucrats is that these actors are the experts in that given policy area. Hence, perhaps they are the ones most qualified to process policy in the given area. Some view the iron triangle idea as outdated. Hugh Heclo of George Mason University has sketched a more open pattern he calls an issue network that includes a number of different interests and political actors that work together in support of a single issue or policy.[23]

Some interest group scholars have studied the relationship among a multitude of interest groups and political actors, including former elected officials, the way some interests form coalitions with other interests, and the way they compete for access to decision-makers.[24]

Some coalitions are long-standing, while others are temporary. Joining coalitions does come with a cost, because it can dilute preferences and split potential benefits that the groups attempt to accrue. Some interest groups will even align themselves with opposing interests if the alliance will achieve their goals. For example, left-leaning groups might oppose a state lottery system because it disproportionately hurts the poor (who participate in this form of gambling at higher rates), while right-leaning groups might oppose it because they view gambling as a sinful activity. These opposing groups might actually join forces in an attempt to defeat the lottery.

While most scholars agree that some interests do have advantages, others have questioned the overwhelming dominance of certain interests. Additionally, neopluralist scholars argue that certainly some interests are in a privileged position, but these interests do not always get what they want.[25]

Instead, their influence depends on a number of factors in the political environment such as public opinion, political culture, competition for access, and the relevance of the issue. Even wealthy interests do not always win if their position is at odds with the wish of an attentive public. And if the public cares about the issue, politicians may be reluctant to defy their constituents. If a prominent manufacturing firm wants fewer regulations on environmental pollutants, and environmental protection is a salient issue to the public, the manufacturing firm may not win in every exchange, despite its resource advantage. We also know that when interests mobilize, opposing interests often counter-mobilize, which can reduce advantages of some interests. Thus, the conclusion that businesses, the wealthy, and elites win in every situation is overstated.[26]

A good example is the recent dispute between fast food chains and their employees. During the spring of 2015, workers at McDonald’s restaurants across the country went on strike and marched in protest of the low wages the fast food giant paid its employees. Despite the opposition of restaurant chains and claims by the National Restaurant Association that increasing the minimum wage would result in the loss of jobs, in September 2015, the state of New York raised the minimum wage for fast food employees to $15 per hour, an amount to be phased in over time. Buoyed by this success, fast food workers in other cities continued to campaign for a pay increase, and many low-paid workers have promised to vote for politicians who plan to boost the federal minimum wage.[27]

Visit the websites for the California or Michigan secretary of state, state boards of elections, or relevant governmental entity and ethics websites where lobbyists and interest groups must register. Several examples are provided but feel free to examine the comparable web page in your own state. Spend some time looking over the lists of interest groups registered in these states. Do the registered interests appear to reflect the important interests within the states? Are there patterns in the types of interests registered? Are certain interests over- or underrepresented?

Summary

Interest groups afford people the opportunity to become more civically engaged. Socioeconomic status is an important predictor of who will likely join groups. The number and types of groups actively lobbying to get what they want from government have been increasing rapidly. Many business and public interest groups have arisen, and many new interests have developed due to technological advances, increased specialization of industry, and fragmentation of interests. Lobbying has also become more sophisticated in recent years, and many interests now hire lobbying firms to represent them.

Some scholars assume that groups will compete for access to decision-makers and that most groups have the potential to be heard. Critics suggest that some groups are advantaged by their access to economic resources. Yet others acknowledge these resource advantages but suggest that the political environment is equally important in determining who gets heard.

| NOTE: The activities below will not be counted towards your final grade for this class. They are strictly here to help you check your knowledge in preparation for class assignments and future dialogue. Best of luck! |

Glossary

- astroturf movement

- a political movement that resembles a grassroots movement but is often supported or facilitated by wealthy interests and/or elites

- efficacy

- the belief that you make a difference and that government cares about you and your views

- elite critique

- the proposition that wealthy and elite interests are advantaged over those without resources

- fragmentation

- the result when a large interest group develops diverging needs

- grassroots movement

- a political movement that often begins from the bottom up, inspired by average citizens concerned about a given issue

- iron triangle

- three-way relationship among congressional committees, interests groups, and the bureaucracy

- issue network

- a group of interest groups and people who work together to support a particular issue or policy

- neopluralist

- a person who suggests that all groups’ access and influence depend on the political environment

- pluralist

- a person who believes many groups healthily compete for access to decision-makers

- See in general Jeffrey M. Berry and Clyde Wilcox. 2008. The Interest Group Society. 5th ed. New York: Routledge. ↵

- David Carter. 2010. Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin. ↵

- http://milkfoundation.org/about/harvey-milk-biography/ (November 8, 2015). ↵

- Clive S. Thomas and Ronald J. Hrebenar. 1990. “Interest Groups in the States.” In Politics in the American States: A Comparative Analysis, 5th ed., eds. Virginia Gray, Herbert Jacob, and Robert B. Albritton. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman, 123–158; Clive S. Thomas and Ronald J. Hrebenar. 1991. “Nationalization of Interest Groups and Lobbying in the States.” In Interest Group Politics, 3d ed., eds. Allan J. Cigler and Burdett A. Loomis. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 63–80; Clive S. Thomas and Ronald J. Hrebenar. 1996. “Interest Groups in the States.” In Politics in the American States: A Comparative Analysis, 6th ed., eds. Virginia Gray, and Herbert Jacob. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 122–158; Clive S. Thomas and Ronald J. Hrebenar. 1999. “Interest Groups in the States.” In Politics in the American States: A Comparative Analysis, 7th ed., eds. Virginia Gray, Russell L. Hanson, and Herbert Jacob. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 113–143; Clive S. Thomas and Ronald J. Hrebenar. 2004. “Interest Groups in the States.” In Politics in the American States: A Comparative Analysis, 8th ed., eds. Virginia Gray and Russell L. Hanson. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 100–128. ↵

- http://www.uspirg.org/ (November 1, 2015). ↵

- Rick Noack, “7 countries where Americans can study at universities, in English, for free (or almost free),” Washington Post, 29 October 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2014/10/29/7-countries-where-americans-can-study-at-universities-in-english-for-free-or-almost-free/. ↵

- Thomas and Hrebenar, “Nationalization of Interest Groups and Lobbying in the States;” Nownes and Newmark, “Interest Groups in the States.” ↵

- Thomas and Hrebenar, “Interest Groups in the States,” 1991, 1996, 1999, 2004; Thomas and Hrebenar, “Nationalization of Interest Groups and Lobbying in the States.” ↵

- Sidney Verba, Kay Lehmnn Schlozman, and Henry Brady. 1995. Voice and Equality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ↵

- Steven J. Rosenstone and John Mark Hansen. 2003. Mobilization, Participation, and Democracy in America. New York: Longman. ↵

- Verba et al., Voice and Equality; Mark J. Rozell, Clyde Wilcox, and Michael M. Franz. 2012. Interest Groups in American Campaigns: The New Face of Electioneering. Oxford University Press: New York. ↵

- Aaron Smith, “Conservative Group’s Times Square Billboard Attacks a $15 Minimum Wage,” 31 August 2015, http://money.cnn.com/2015/08/31/news/economy/times-square-minimum-wage/. ↵

- Robert Putnam. 2000. Bowling Alone. New York: Simon and Shuster; Rosenstone and Hansen, Mobilization, Participation and Democracy in America. ↵

- David B. Truman 1951. The Governmental Process: Political Interests and Public Opinion. New York: Knopf. ↵

- Dahl, Robert A. 1956. A Preface to Democratic Theory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; Dahl, Robert A. 1961. Who Governs? Democracy and Power in an American City. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ↵

- E. E. Schattschneider. 1960. The Semisovereign People: A Realist’s View of Democracy in America. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 35. ↵

- W. G. Domhoff. 2009. Who rules America? Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; K. L. Schlozman, “What Accent the Heavenly choir? Political Equality and the American Pressure System,” Journal of Politics 46, No. 2 (1984) 1006–1032; K. L. Schlozman, S. Verba, and H. E. Brady. 2012. The Unheavenly Chorus: Unequal Political Voice and the Broken Promise of American Democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ↵

- Olson, Jr., The Logic of Collective Action. ↵

- Kevin Drum, “Nobody Cares What You Think Unless You’re Rich,” Mother Jones, 8 April 2014, http://www.motherjones.com/kevin-drum/2014/04/nobody-cares-what-you-think-unless-youre-rich. ↵

- Larry Bartels, “Rich People Rule!” Washington Post, 8 April 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2014/04/08/rich-people-rule. ↵

- Frank R. Baumgartner and Beth L. Leech. 1998. Basic Interests: The Importance of Groups in Political Science. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ↵

- Francis E. Rourke. 1984. Bureaucracy, Politics, and Public Policy, 3rd ed. NY: Harper Collins. ↵

- Hugh Heclo. 1984. “Issue Networks and the Executive Establishment.” In The New American Political System, ed. Anthony King. Washington DC: The American Enterprise Institute, 87–124. ↵

- V. Gray and D. Lowery, “To Lobby Alone or in a Flock: Foraging Behavior among Organized Interests,” American Politics Research 26, No. 1 (1998): 5–34; M. Hojnacki, “Interest Groups’ Decisions to Join Alliances or Work Alone,” American Journal of Political Science 41, No. 1 (1997): 61–87; Kevin W. Hula. 1999. Lobbying Together: Interest Group Coalitions in Legislative Politics. Washington DC: Georgetown University Press. ↵

- Virginia Gray and David Lowery. 1996. The Population Ecology of Interest Representation: Lobbying Communities in the American States. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; Andrew S. McFarland. 2004. Neopluralism. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. ↵

- Mark A. Smith. 2000. American Business and Political Power: Public Opinion, Elections, and Democracy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; F. R. Baumgartner, J. M. Berry, M. Hojnacki, D. C. Kimball, and B. L. Leech. 2009, Lobbying and Policy Change. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ↵

- Patrick McGeehan, “New York Plans $15-an-Hour Minimum Wage for Fast Food Workers,” New York Times, 22 July 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/23/nyregion/new-york-minimum-wage-fast-food-workers.html; Paul Davidson, “Fast-Food Workers Strike, Seeing $15 Wage, Political Muscle,” USA Today, 10 November 2015 http://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2015/11/10/fast-food-strikes-begin/75482782/. ↵