Chapter 13: The Courts

Guardians of the Constitution and Individual Rights

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the evolving role of the courts since the ratification of the Constitution

- Explain why courts are uniquely situated to protect individual rights

- Recognize how the courts make public policy

Under the Articles of Confederation, there was no national judiciary. The U.S. Constitution changed that, but its Article III, which addresses “the judicial power of the United States,” is the shortest and least detailed of the three articles that created the branches of government. It calls for the creation of “one supreme Court” and establishes the Court’s jurisdiction, or its authority to hear cases and make decisions about them, and the types of cases the Court may hear. It distinguishes which are matters of original jurisdiction and which are for appellate jurisdiction. Under original jurisdiction, a case is heard for the first time, whereas under appellate jurisdiction, a court hears a case on appeal from a lower court and may change the lower court’s decision. The Constitution also limits the Supreme Court’s original jurisdiction to those rare cases of disputes between states, or between the United States and foreign ambassadors or ministers. So, for the most part, the Supreme Court is an appeals court, operating under appellate jurisdiction and hearing appeals from the lower courts. The rest of the development of the judicial system and the creation of the lower courts were left in the hands of Congress.

To add further explanation to Article III, Alexander Hamilton wrote details about the federal judiciary in Federalist No. 78. In explaining the importance of an independent judiciary separated from the other branches of government, he said “interpretation” was a key role of the courts as they seek to protect people from unjust laws. But he also believed “the Judiciary Department” would “always be the least dangerous” because “with no influence over either the sword or the purse,” it had “neither force nor will, but merely judgment.” The courts would only make decisions, not take action. With no control over how those decisions would be implemented and no power to enforce their choices, they could exercise only judgment, and their power would begin and end there. Hamilton would no doubt be surprised by what the judiciary has become: a key component of the nation’s constitutional democracy, finding its place as the chief interpreter of the Constitution and the equal of the other two branches, though still checked and balanced by them.

The first session of the first U.S. Congress laid the framework for today’s federal judicial system, established in the Judiciary Act of 1789. Although legislative changes over the years have altered it, the basic structure of the judicial branch remains as it was set early on: At the lowest level are the district courts, where federal cases are tried, witnesses testify, and evidence and arguments are presented. A losing party who is unhappy with a district court decision may appeal to the circuit courts, or U.S. courts of appeals, where the decision of the lower court is reviewed. Still further, appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court is possible, but of the thousands of petitions for appeal, the Supreme Court will typically hear fewer than one hundred a year.[1]

HUMBLE BEGINNINGS

Starting in New York in 1790, the early Supreme Court focused on establishing its rules and procedures and perhaps trying to carve its place as the new government’s third branch. However, given the difficulty of getting all the justices even to show up, and with no permanent home or building of its own for decades, finding its footing in the early days proved to be a monumental task. Even when the federal government moved to the nation’s capital in 1800, the Court had to share space with Congress in the Capitol building. This ultimately meant that “the high bench crept into an undignified committee room in the Capitol beneath the House Chamber.”[2]

It was not until the Court’s 146th year of operation that Congress, at the urging of Chief Justice—and former president—William Howard Taft, provided the designation and funding for the Supreme Court’s own building, “on a scale in keeping with the importance and dignity of the Court and the Judiciary as a coequal, independent branch of the federal government.”[3]

It was a symbolic move that recognized the Court’s growing role as a significant part of the national government ((Figure)).

Figure 1. The Supreme Court building in Washington, DC, was not completed until 1935. Engraved on its marble front is the motto “Equal Justice Under Law,” while its east side says, “Justice, the Guardian of Liberty.”

But it took years for the Court to get to that point, and it faced a number of setbacks on the way to such recognition. In their first case of significance, Chisholm v. Georgia (1793), the justices ruled that the federal courts could hear cases brought by a citizen of one state against a citizen of another state, and that Article III, Section 2, of the Constitution did not protect the states from facing such an interstate lawsuit.[4]

However, their decision was almost immediately overturned by the Eleventh Amendment, passed by Congress in 1794 and ratified by the states in 1795. In protecting the states, the Eleventh Amendment put a prohibition on the courts by stating, “The Judicial power of the United States shall not be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, commenced or prosecuted against one of the United States by Citizens of another State, or by Citizens or Subjects of any Foreign State.” It was an early hint that Congress had the power to change the jurisdiction of the courts as it saw fit and stood ready to use it.

In an atmosphere of perceived weakness, the first chief justice, John Jay, an author of The Federalist Papers and appointed by President George Washington, resigned his post to become governor of New York and later declined President John Adams’s offer of a subsequent term.[5]

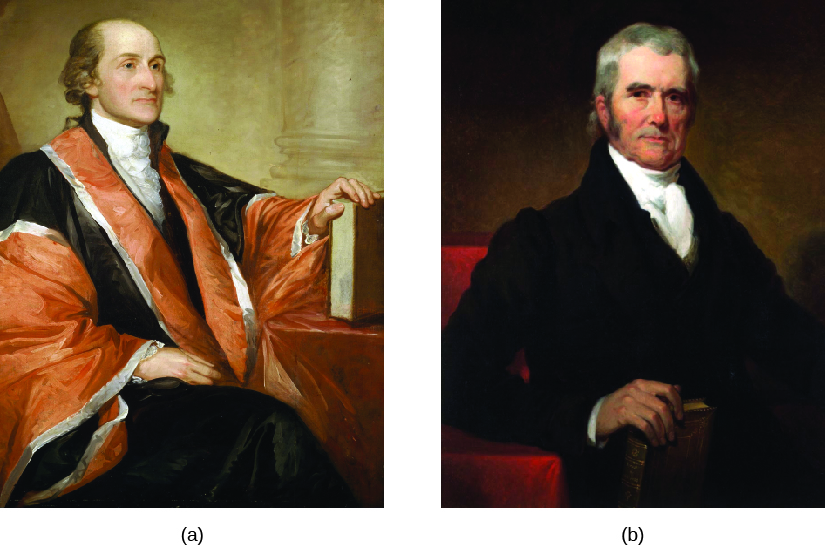

In fact, the Court might have remained in a state of what Hamilton called its “natural feebleness” if not for the man who filled the vacancy Jay had refused—the fourth chief justice, John Marshall. Often credited with defining the modern court, clarifying its power, and strengthening its role, Marshall served in the chief’s position for thirty-four years. One landmark case during his tenure changed the course of the judicial branch’s history ((Figure)).[6]

Figure 2. John Jay (a) was the first chief justice of the Supreme Court but resigned his post to become governor of New York. John Marshall (b), who served as chief justice for thirty-four years, is often credited as the major force in defining the modern court’s role in the U.S. governmental system.

In 1803, the Supreme Court declared for itself the power of judicial review, a power to which Hamilton had referred but that is not expressly mentioned in the Constitution. Judicial review is the power of the courts, as part of the system of checks and balances, to look at actions taken by the other branches of government and the states and determine whether they are constitutional. If the courts find an action to be unconstitutional, it becomes null and void. Judicial review was established in the Supreme Court case Marbury v. Madison, when, for the first time, the Court declared an act of Congress to be unconstitutional.[7]

Wielding this power is a role Marshall defined as the “very essence of judicial duty,” and it continues today as one of the most significant aspects of judicial power. Judicial review lies at the core of the court’s ability to check the other branches of government—and the states.

Since Marbury, the power of judicial review has continually expanded, and the Court has not only ruled actions of Congress and the president to be unconstitutional, but it has also extended its power to include the review of state and local actions. The power of judicial review is not confined to the Supreme Court but is also exercised by the lower federal courts and even the state courts. Any legislative or executive action at the federal or state level inconsistent with the U.S. Constitution or a state constitution can be subject to judicial review.[8]

|

Marbury v. Madison(1803) The Supreme Court found itself in the middle of a dispute between the outgoing presidential administration of John Adams and that of incoming president (and opposition party member) Thomas Jefferson. It was an interesting circumstance at the time, particularly because Jefferson and the man who would decide the case—John Marshall—were themselves political rivals. President Adams had appointed William Marbury to a position in Washington, DC, but his commission was not delivered before Adams left office. So Marbury petitioned the Supreme Court to use its power under the Judiciary Act of 1789 and issue a writ of mandamus to force the new president’s secretary of state, James Madison, to deliver the commission documents. It was a task Madison refused to do. A unanimous Court under the leadership of Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that although Marbury was entitled to the job, the Court did not have the power to issue the writ and order Madison to deliver the documents, because the provision in the Judiciary Act that had given the Court that power was unconstitutional.[9] Perhaps Marshall feared a confrontation with the Jefferson administration and thought Madison would refuse his directive anyway. In any case, his ruling shows an interesting contrast in the early Court. On one hand, it humbly declined a power—issuing a writ of mandamus—given to it by Congress, but on the other, it laid the foundation for legitimizing a much more important one—judicial review. Marbury never got his commission, but the Court’s ruling in the case has become more significant for the precedent it established: As the first time the Court declared an act of Congress unconstitutional, it established the power of judicial review, a key power that enables the judicial branch to remain a powerful check on the other branches of government. Consider the dual nature of John Marshall’s opinion in Marbury v. Madison: On one hand, it limits the power of the courts, yet on the other it also expanded their power. Explain the different aspects of the decision in terms of these contrasting results. |

THE COURTS AND PUBLIC POLICY

Even with judicial review in place, the courts do not always stand ready just to throw out actions of the other branches of government. More broadly, as Marshall put it, “it is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.”[10]

The United States has a common law system in which law is largely developed through binding judicial decisions. With roots in medieval England, the system was inherited by the American colonies along with many other British traditions.[11]

It stands in contrast to code law systems, which provide very detailed and comprehensive laws that do not leave room for much interpretation and judicial decision-making. With code law in place, as it is in many nations of the world, it is the job of judges to simply apply the law. But under common law, as in the United States, they interpret it. Often referred to as a system of judge-made law, common law provides the opportunity for the judicial branch to have stronger involvement in the process of law-making itself, largely through its ruling and interpretation on a case-by-case basis.

In their role as policymakers, Congress and the president tend to consider broad questions of public policy and their costs and benefits. But the courts consider specific cases with narrower questions, thus enabling them to focus more closely than other government institutions on the exact context of the individuals, groups, or issues affected by the decision. This means that while the legislature can make policy through statute, and the executive can form policy through regulations and administration, the judicial branch can also influence policy through its rulings and interpretations. As cases are brought to the courts, court decisions can help shape policy.

Consider health care, for example. In 2010, President Barack Obama signed into law the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), a statute that brought significant changes to the nation’s healthcare system. With its goal of providing more widely attainable and affordable health insurance and health care, “Obamacare” was hailed by some but soundly denounced by others as bad policy. People who opposed the law and understood that a congressional repeal would not happen any time soon looked to the courts for help. They challenged the constitutionality of the law in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, hoping the Supreme Court would overturn it.[12]

The practice of judicial review enabled the law’s critics to exercise this opportunity, even though their hopes were ultimately dashed when, by a narrow 5–4 margin, the Supreme Court upheld the health care law as a constitutional extension of Congress’s power to tax.

Since this 2012 decision, the ACA has continued to face challenges, the most notable of which have also been decided by court rulings. It faced a setback in 2014, for instance, when the Supreme Court ruled in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby that, for religious reasons, some for-profit corporations could be exempt from the requirement that employers provide insurance coverage of contraceptives for their female employees.[13]

But the ACA also attained a victory in King v. Burwell, when the Court upheld the ability of the federal government to provide tax credits for people who bought their health insurance through an exchange created by the law.[14]

With each ACA case it has decided, the Supreme Court has served as the umpire, upholding the law and some of its provisions on one hand, but ruling some aspects of it unconstitutional on the other. Both supporters and opponents of the law have claimed victory and faced defeat. In each case, the Supreme Court has further defined and fine-tuned the law passed by Congress and the president, determining which parts stay and which parts go, thus having its say in the way the act has manifested itself, the way it operates, and the way it serves its public purpose.

In this same vein, the courts have become the key interpreters of the U.S. Constitution, continuously interpreting it and applying it to modern times and circumstances. For example, it was in 2015 that we learned a man’s threat to kill his ex-wife, written in rap lyrics and posted to her Facebook wall, was not a real threat and thus could not be prosecuted as a felony under federal law.[15]

Certainly, when the Bill of Rights first declared that government could not abridge freedom of speech, its framers could never have envisioned Facebook—or any other modern technology for that matter.

But freedom of speech, just like many constitutional concepts, has come to mean different things to different generations, and it is the courts that have designed the lens through which we understand the Constitution in modern times. It is often said that the Constitution changes less by amendment and more by the way it is interpreted. Rather than collecting dust on a shelf, the nearly 230-year-old document has come with us into the modern age, and the accepted practice of judicial review has helped carry it along the way.

COURTS AS A LAST RESORT

While the U.S. Supreme Court and state supreme courts exert power over many when reviewing laws or declaring acts of other branches unconstitutional, they become particularly important when an individual or group comes before them believing there has been a wrong. A citizen or group that feels mistreated can approach a variety of institutional venues in the U.S. system for assistance in changing policy or seeking support. Organizing protests, garnering special interest group support, and changing laws through the legislative and executive branches are all possible, but an individual is most likely to find the courts especially well-suited to analyzing the particulars of his or her case.

The adversarial judicial system comes from the common law tradition: In a court case, it is one party versus the other, and it is up to an impartial person or group, such as the judge or jury, to determine which party prevails. The federal court system is most often called upon when a case touches on constitutional rights. For example, when Samantha Elauf, a Muslim woman, was denied a job working for the clothing retailer Abercrombie & Fitch because a headscarf she wears as religious practice violated the company’s dress code, the Supreme Court ruled that her First Amendment rights had been violated, making it possible for her to sue the store for monetary damages.

Elauf had applied for an Abercrombie sales job in Oklahoma in 2008. Her interviewer recommended her based on her qualifications, but she was never given the job because the clothing retailer wanted to avoid having to accommodate her religious practice of wearing a headscarf, or hijab. In so doing, the Court ruled, Abercrombie violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits employers from discriminating on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, and requires them to accommodate religious practices.[16]

Rulings like this have become particularly important for members of religious minority groups, including Muslims, Sikhs, and Jews, who now feel more protected from employment discrimination based on their religious attire, head coverings, or beards.[17]

Such decisions illustrate how the expansion of individual rights and liberties for particular persons or groups over the years has come about largely as a result of court rulings made for individuals on a case-by-case basis.

Although the United States prides itself on the Declaration of Independence’s statement that “all men are created equal,” and “equal protection of the laws” is a written constitutional principle of the Fourteenth Amendment, the reality is less than perfect. But it is evolving. Changing times and technology have and will continue to alter the way fundamental constitutional rights are defined and applied, and the courts have proven themselves to be crucial in that definition and application.

Societal traditions, public opinion, and politics have often stood in the way of the full expansion of rights and liberties to different groups, and not everyone has agreed that these rights should be expanded as they have been by the courts. Schools were long segregated by race until the Court ordered desegregation in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), and even then, many stood in opposition and tried to block students at the entrances to all-white schools.[18]

Factions have formed on opposite sides of the abortion and handgun debates, because many do not agree that women should have abortion rights or that individuals should have the right to a handgun. People disagree about whether members of the LGBT community should be allowed to marry or whether arrested persons should be read their rights, guaranteed an attorney, and/or have their cell phones protected from police search.

But the Supreme Court has ruled in favor of all these issues and others. Even without unanimous agreement among citizens, Supreme Court decisions have made all these possibilities a reality, a particularly important one for the individuals who become the beneficiaries ((Figure)). The judicial branch has often made decisions the other branches were either unwilling or unable to make, and Hamilton was right in Federalist No. 78 when he said that without the courts exercising their duty to defend the Constitution, “all the reservations of particular rights or privileges would amount to nothing.”

| Examples of Supreme Court Cases Involving Individuals | ||

|---|---|---|

| Case Name | Year | Court’s Decision |

| Brown v. Board of Education | 1954 | Public schools must be desegregated. |

| Gideon v. Wainwright | 1963 | Poor criminal defendants must be provided an attorney. |

| Miranda v. Arizona | 1966 | Criminal suspects must be read their rights. |

| Roe v. Wade | 1973 | Women have a constitutional right to abortion. |

| McDonald v. Chicago | 2010 | An individual has the right to a handgun in his or her home. |

| Riley v. California | 2014 | Police may not search a cell phone without a warrant. |

| Obergefell v. Hodges | 2015 | Same-sex couples have the right to marry in all states. |

The courts seldom if ever grant rights to a person instantly and upon request. In a number of cases, they have expressed reluctance to expand rights without limit, and they still balance that expansion with the government’s need to govern, provide for the common good, and serve a broader societal purpose. For example, the Supreme Court has upheld the constitutionality of the death penalty, ruling that the Eighth Amendment does not prevent a person from being put to death for committing a capital crime and that the government may consider “retribution and the possibility of deterrence” when it seeks capital punishment for a crime that so warrants it.[19]

In other words, there is a greater good—more safety and security—that may be more important than sparing the life of an individual who has committed a heinous crime.

Yet the Court has also put limits on the ability to impose the death penalty, ruling, for example, that the government may not execute a person with cognitive disabilities, a person who was under eighteen at the time of the crime, or a child rapist who did not kill his victim.[20]

So the job of the courts on any given issue is never quite done, as justices continuously keep their eye on government laws, actions, and policy changes as cases are brought to them and then decide whether those laws, actions, and policies can stand or must go. Even with an issue such as the death penalty, about which the Court has made several rulings, there is always the possibility that further judicial interpretation of what does (or does not) violate the Constitution will be needed.

This happened, for example, as recently as 2015 in a case involving the use of lethal injection as capital punishment in the state of Oklahoma, where death-row inmates are put to death through the use of three drugs—a sedative to bring about unconsciousness (midazolam), followed by two others that cause paralysis and stop the heart. A group of these inmates challenged the use of midazolam as unconstitutional. They argued that since it could not reliably cause unconsciousness, its use constituted an Eighth Amendment violation against cruel and unusual punishment and should be stopped by the courts. The Supreme Court rejected the inmates’ claims, ruling that Oklahoma could continue to use midazolam as part of its three-drug protocol.[21]

But with four of the nine justices dissenting from that decision, a sharply divided Court leaves open a greater possibility of more death-penalty cases to come. The 2015–2016 session alone includes four such cases, challenging death-sentencing procedures in such states as Florida, Georgia, and Kansas.[22]

Therefore, we should not underestimate the power and significance of the judicial branch in the United States. Today, the courts have become a relevant player, gaining enough clout and trust over the years to take their place as a separate yet coequal branch.

Summary

From humble beginnings, the judicial branch has evolved over the years to a significance that would have been difficult for the Constitution’s framers to envision. While they understood and prioritized the value of an independent judiciary in a common law system, they could not have predicted the critical role the courts would play in the interpretation of the Constitution, our understanding of the law, the development of public policy, and the preservation and expansion of individual rights and liberties over time.

| NOTE: The activities below will not be counted towards your final grade for this class. They are strictly here to help you check your knowledge in preparation for class assignments and future dialogue. Best of luck! |

Glossary

- appellate jurisdiction

- the power of a court to hear a case on appeal from a lower court and possibly change the lower court’s decision

- common law

- the pattern of law developed by judges through case decisions largely based on precedent

- judicial review

- the power of the courts to review actions taken by the other branches of government and the states and to rule on whether those actions are constitutional

- Marbury v. Madison

- the 1803 Supreme Court case that established the courts’ power of judicial review and the first time the Supreme Court ruled an act of Congress to be unconstitutional

- original jurisdiction

- the power of a court to hear a case for the first time

- “The U.S. Supreme Court.” The Judicial Learning Center. http://judiciallearningcenter.org/the-us-supreme-court/ (March 1, 2016). ↵

- Bernard Schwartz. 1993. A History of the Supreme Court. New York: Oxford University Press, 16. ↵

- “Washington D.C. A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary.” U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. http://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/wash/dc78.htm (March 1, 2016). ↵

- Chisholm v. Georgia, 2 U.S. 419 (1793). ↵

- Associated Press. “What You Should Know About Forgotten Founding Father John Jay,” PBS Newshour. July 4, 2015. http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/forgotten-founding-father. ↵

- “Life and Legacy.” The John Marshall Foundation. http://www.johnmarshallfoundation.org (March 1, 2016). ↵

- Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803). ↵

- Stephen Hass. “Judicial Review.” National Juris University. http://juris.nationalparalegal.edu/(X(1)S(wwbvsi5iswopllt1bfpzfkjd))/JudicialReview.aspx (March 1, 2016). ↵

- Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803). ↵

- Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803). ↵

- “The Common Law and Civil Law Traditions.” The Robbins Collection. School of Law (Boalt Hall). University of California at Berkeley. https://www.law.berkeley.edu/library/robbins/CommonLawCivilLawTraditions.html (March 1, 2016). ↵

- National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, 567 U.S. __ (2012). ↵

- Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, 573 U.S. __ (2014). ↵

- King v. Burwell, 576 U.S. __ (2015). ↵

- Elonis v. United States, 13-983 U.S. __ (2015). ↵

- Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Abercrombie & Fitch Stores, 575 U.S. __ (2015). ↵

- Liptak, Adam. “Muslim Woman Denied Job Over Head Scarf Wins in Supreme Court.” New York Times. 1 June 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/02/us/supreme-court-rules-in-samantha-elauf-abercrombie-fitch-case.html?_r=0. ↵

- Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). ↵

- Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 (1976). ↵

- Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304 (2002); Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005); Kennedy v. Louisiana, 554 U.S. 407 (2008). ↵

- Glossip v. Gross, 576 U.S. __ (2015). ↵

- “October Term 2015.” SCOTUSblog. http://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/terms/ot2015/?sort=mname (March 1, 2016). ↵