Chapter 15: The Bureaucracy

Bureaucracy and the Evolution of Public Administration

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define bureaucracy and bureaucrat

- Describe the evolution and growth of public administration in the United States

- Identify the reasons people undertake civil service

Throughout history, both small and large nations have elevated certain types of nonelected workers to positions of relative power within the governmental structure. Collectively, these essential workers are called the bureaucracy. A bureaucracy is an administrative group of nonelected officials charged with carrying out functions connected to a series of policies and programs. In the United States, the bureaucracy began as a very small collection of individuals. Over time, however, it grew to be a major force in political affairs. Indeed, it grew so large that politicians in modern times have ridiculed it to great political advantage. However, the country’s many bureaucrats or civil servants, the individuals who work in the bureaucracy, fill necessary and even instrumental roles in every area of government: from high-level positions in foreign affairs and intelligence collection agencies to clerks and staff in the smallest regulatory agencies. They are hired, or sometimes appointed, for their expertise in carrying out the functions and programs of the government.

WHAT DOES A BUREAUCRACY DO?

Modern society relies on the effective functioning of government to provide public goods, enhance quality of life, and stimulate economic growth. The activities by which government achieves these functions include—but are not limited to—taxation, homeland security, immigration, foreign affairs, and education. The more society grows and the need for government services expands, the more challenging bureaucratic management and public administration becomes. Public administration is both the implementation of public policy in government bureaucracies and the academic study that prepares civil servants for work in those organizations.

The classic version of a bureaucracy is hierarchical and can be described by an organizational chart that outlines the separation of tasks and worker specialization while also establishing a clear unity of command by assigning each employee to only one boss. Moreover, the classic bureaucracy employs a division of labor under which work is separated into smaller tasks assigned to different people or groups. Given this definition, bureaucracy is not unique to government but is also found in the private and nonprofit sectors. That is, almost all organizations are bureaucratic regardless of their scope and size; although public and private organizations differ in some important ways. For example, while private organizations are responsible to a superior authority such as an owner, board of directors, or shareholders, federal governmental organizations answer equally to the president, Congress, the courts, and ultimately the public. The underlying goals of private and public organizations also differ. While private organizations seek to survive by controlling costs, increasing market share, and realizing a profit, public organizations find it more difficult to measure the elusive goal of operating with efficiency and effectiveness.

Bureaucracy may seem like a modern invention, but bureaucrats have served in governments for nearly as long as governments have existed. Archaeologists and historians point to the sometimes elaborate bureaucratic systems of the ancient world, from the Egyptian scribes who recorded inventories to the biblical tax collectors who kept the wheels of government well greased.[1]

In Europe, government bureaucracy and its study emerged before democracies did. In contrast, in the United States, a democracy and the Constitution came first, followed by the development of national governmental organizations as needed, and then finally the study of U.S. government bureaucracies and public administration emerged.[2]

In fact, the long pedigree of bureaucracy is an enduring testament to the necessity of administrative organization. More recently, modern bureaucratic management emerged in the eighteenth century from Scottish economist Adam Smith’s support for the efficiency of the division of labor and from Welsh reformer Robert Owen’s belief that employees are vital instruments in the functioning of an organization. However, it was not until the mid-1800s that the German scholar Lorenz von Stein argued for public administration as both a theory and a practice since its knowledge is generated and evaluated through the process of gathering evidence. For example, a public administration scholar might gather data to see whether the timing of tax collection during a particular season might lead to higher compliance or returns. Credited with being the father of the science of public administration, von Stein opened the path of administrative enlightenment for other scholars in industrialized nations.

THE ORIGINS OF THE U.S. BUREAUCRACY

In the early U.S. republic, the bureaucracy was quite small. This is understandable since the American Revolution was largely a revolt against executive power and the British imperial administrative order. Nevertheless, while neither the word “bureaucracy” nor its synonyms appear in the text of the Constitution, the document does establish a few broad channels through which the emerging government could develop the necessary bureaucratic administration.

For example, Article II, Section 2, provides the president the power to appoint officers and department heads. In the following section, the president is further empowered to see that the laws are “faithfully executed.” More specifically, Article I, Section 8, empowers Congress to establish a post office, build roads, regulate commerce, coin money, and regulate the value of money. Granting the president and Congress such responsibilities appears to anticipate a bureaucracy of some size. Yet the design of the bureaucracy is not described, and it does not occupy its own section of the Constitution as bureaucracy often does in other countries’ governing documents; the design and form were left to be established in practice.

Under President George Washington, the bureaucracy remained small enough to accomplish only the necessary tasks at hand.[3]

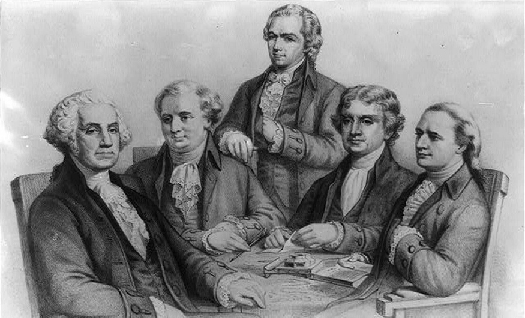

Washington’s tenure saw the creation of the Department of State to oversee international issues, the Department of the Treasury to control coinage, and the Department of War to administer the armed forces. The employees within these three departments, in addition to the growing postal service, constituted the major portion of the federal bureaucracy for the first three decades of the republic ((Figure)). Two developments, however, contributed to the growth of the bureaucracy well beyond these humble beginnings.

Figure 1. The cabinet of President George Washington (far left) consisted of only four individuals: the secretary of war (Henry Knox, left), the secretary of the treasury (Alexander Hamilton, center), the secretary of state (Thomas Jefferson, right), and the attorney general (Edmund Randolph, far right). The small size of this group reflected the small size of the U.S. government in the late eighteenth century. (credit: modification of work by the Library of Congress)

The first development was the rise of centralized party politics in the 1820s. Under President Andrew Jackson, many thousands of party loyalists filled the ranks of the bureaucratic offices around the country. This was the beginning of the spoils system, in which political appointments were transformed into political patronage doled out by the president on the basis of party loyalty.[4]

Political patronage is the use of state resources to reward individuals for their political support. The term “spoils” here refers to paid positions in the U.S. government. As the saying goes, “to the victor,” in this case the incoming president, “go the spoils.” It was assumed that government would work far more efficiently if the key federal posts were occupied by those already supportive of the president and his policies. This system served to enforce party loyalty by tying the livelihoods of the party faithful to the success or failure of the party. The number of federal posts the president sought to use as appropriate rewards for supporters swelled over the following decades.

The second development was industrialization, which in the late nineteenth century significantly increased both the population and economic size of the United States. These changes in turn brought about urban growth in a number of places across the East and Midwest. Railroads and telegraph lines drew the country together and increased the potential for federal centralization. The government and its bureaucracy were closely involved in creating concessions for and providing land to the western railways stretching across the plains and beyond the Rocky Mountains. These changes set the groundwork for the regulatory framework that emerged in the early twentieth century.

THE FALL OF POLITICAL PATRONAGE

Patronage had the advantage of putting political loyalty to work by making the government quite responsive to the electorate and keeping election turnout robust because so much was at stake. However, the spoils system also had a number of obvious disadvantages. It was a reciprocal system. Clients who wanted positions in the civil service pledged their political loyalty to a particular patron who then provided them with their desired positions. These arrangements directed the power and resources of government toward perpetuating the reward system. They replaced the system that early presidents like Thomas Jefferson had fostered, in which the country’s intellectual and economic elite rose to the highest levels of the federal bureaucracy based on their relative merit.[5]

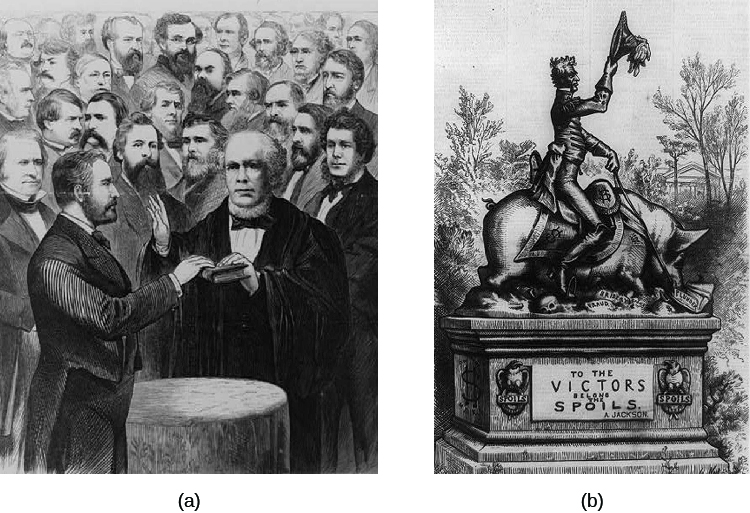

Criticism of the spoils system grew, especially in the mid-1870s, after numerous scandals rocked the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant ((Figure)).

Figure 2. Caption: It was under President Ulysses S. Grant, shown in this engraving being sworn in by Chief Justice Samuel P. Chase at his inauguration in 1873 (a), that the inefficiencies and opportunities for corruption embedded in the spoils system reached their height. Grant was famously loyal to his supporters, a characteristic that—combined with postwar opportunities for corruption—created scandal in his administration. This political cartoon from 1877 (b), nearly half a century after Andrew Jackson was elected president, ridicules the spoils system that was one of his legacies. In it he is shown riding a pig, which is walking over “fraud,” “bribery,” and “spoils” and feeding on “plunder.” (credit a, b: modification of work by the Library of Congress)

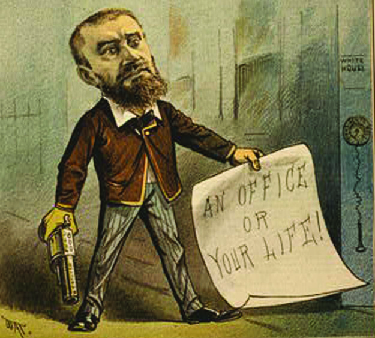

As the negative aspects of political patronage continued to infect bureaucracy in the late nineteenth century, calls for civil service reform grew louder. Those supporting the patronage system held that their positions were well earned; those who condemned it argued that federal legislation was needed to ensure jobs were awarded on the basis of merit. Eventually, after President James Garfield had been assassinated by a disappointed office seeker ((Figure)), Congress responded to cries for reform with the Pendleton Act, also called the Civil Service Reform Act of 1883. The act established the Civil Service Commission, a centralized agency charged with ensuring that the federal government’s selection, retention, and promotion practices were based on open, competitive examinations in a merit system.

The passage of this law sparked a period of social activism and political reform that continued well into the twentieth century.

Figure 3. In 1881, after the election of James Garfield, a disgruntled former supporter of his, the failed lawyer Charles J. Guiteau, shot him in the back. Guiteau (pictured in this cartoon of the time) had convinced himself he was due an ambassadorship for his work in electing the president. The assassination awakened the nation to the need for civil service reform. (credit: modification of work by the Library of Congress)

As an active member and leader of the Progressive movement, President Woodrow Wilson is often considered the father of U.S. public administration. Born in Virginia and educated in history and political science at Johns Hopkins University, Wilson became a respected intellectual in his fields with an interest in public service and a profound sense of moralism. He was named president of Princeton University, became president of the American Political Science Association, was elected governor of New Jersey, and finally was elected the twenty-eighth president of the United States in 1912.

It was through his educational training and vocational experiences that Wilson began to identify the need for a public administration discipline. He felt it was getting harder to run a constitutional government than to actually frame one. His stance was that “It is the object of administrative study to discover, first, what government can properly and successfully do, and, secondly, how it can do these proper things with the utmost efficiency. . .”[6]

Wilson declared that while politics does set tasks for administration, public administration should be built on a science of management, and political science should be concerned with the way governments are administered. Therefore, administrative activities should be devoid of political manipulations.[7]

Wilson advocated separating politics from administration by three key means: making comparative analyses of public and private organizations, improving efficiency with business-like practices, and increasing effectiveness through management and training. Wilson’s point was that while politics should be kept separate from administration, administration should not be insensitive to public opinion. Rather, the bureaucracy should act with a sense of vigor to understand and appreciate public opinion. Still, Wilson acknowledged that the separation of politics from administration was an ideal and not necessarily an achievable reality.

THE BUREAUCRACY COMES OF AGE

The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were a time of great bureaucratic growth in the United States: The Interstate Commerce Commission was established in 1887, the Federal Reserve Board in 1913, the Federal Trade Commission in 1914, and the Federal Power Commission in 1920.

With the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, the United States faced record levels of unemployment and the associated fall into poverty, food shortages, and general desperation. When the Republican president and Congress were not seen as moving aggressively enough to fix the situation, the Democrats won the 1932 election in overwhelming fashion. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the U.S. Congress rapidly reorganized the government’s problem-solving efforts into a series of programs designed to revive the economy, stimulate economic development, and generate employment opportunities. In the 1930s, the federal bureaucracy grew with the addition of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation to protect and regulate U.S. banking, the National Labor Relations Board to regulate the way companies could treat their workers, the Securities and Exchange Commission to regulate the stock market, and the Civil Aeronautics Board to regulate air travel. Additional programs and institutions emerged with the Social Security Administration in 1935 and then, during World War II, various wartime boards and agencies. By 1940, approximately 700,000 U.S. workers were employed in the federal bureaucracy.[8]

Under President Lyndon B. Johnson in the 1960s, that number reached 2.2 million, and the federal budget increased to $332 billion.[9]

This growth came as a result of what Johnson called his Great Society program, intended to use the power of government to relieve suffering and accomplish social good. The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 was designed to help end poverty by creating a Job Corps and a Neighborhood Youth Corps. Volunteers in Service to America was a type of domestic Peace Corps intended to relieve the effects of poverty. Johnson also directed more funding to public education, created Medicare as a national insurance program for the elderly, and raised standards for consumer products.

All of these new programs required bureaucrats to run them, and the national bureaucracy naturally ballooned. Its size became a rallying cry for conservatives, who eventually elected Ronald Reagan president for the express purpose of reducing the bureaucracy. While Reagan was able to work with Congress to reduce some aspects of the federal bureaucracy, he contributed to its expansion in other ways, particularly in his efforts to fight the Cold War.[10]

For example, Reagan and Congress increased the defense budget dramatically over the course of the 1980s.[11]

|

“The Nine Most Terrifying Words in the English Language” The two periods of increased bureaucratic growth in the United States, the 1930s and the 1960s, accomplished far more than expanding the size of government. They transformed politics in ways that continue to shape political debate today. While the bureaucracies created in these two periods served important purposes, many at that time and even now argue that the expansion came with unacceptable costs, particularly economic costs. The common argument that bureaucratic regulation smothers capitalist innovation was especially powerful in the Cold War environment of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. But as long as voters felt they were benefiting from the bureaucratic expansion, as they typically did, the political winds supported continued growth. In the 1970s, however, Germany and Japan were thriving economies in positions to compete with U.S. industry. This competition, combined with technological advances and the beginnings of computerization, began to eat away at American prosperity. Factories began to close, wages began to stagnate, inflation climbed, and the future seemed a little less bright. In this environment, tax-paying workers were less likely to support generous welfare programs designed to end poverty. They felt these bureaucratic programs were adding to their misery in order to support unknown others. In his first and unsuccessful presidential bid in 1976, Ronald Reagan, a skilled politician and governor of California, stoked working-class anxieties by directing voters’ discontent at the bureaucratic dragon he proposed to slay. When he ran again four years later, his criticism of bureaucratic waste in Washington carried him to a landslide victory. While it is debatable whether Reagan actually reduced the size of government, he continued to wield rhetoric about bureaucratic waste to great political advantage. Even as late as 1986, he continued to rail against the Washington bureaucracy ((Figure)), once declaring famously that “the nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.”  Figure 4. As seen in this 1976 photograph, President Ronald Reagan frequently and intentionally dressed in casual clothing to symbolize his distance from the government machinery he loved to criticize. (credit: Ronald Reagan Library) Why might people be more sympathetic to bureaucratic growth during periods of prosperity? In what way do modern politicians continue to stir up popular animosity against bureaucracy to political advantage? Is it effective? Why or why not? |

Summary

During the post-Jacksonian era of the nineteenth century, the common charge against the bureaucracy was that it was overly political and corrupt. This changed in the 1880s as the United States began to create a modern civil service. The civil service grew once again in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration as he expanded government programs to combat the effects of the Great Depression. The most recent criticisms of the federal bureaucracy, notably under Ronald Reagan, emerged following the second great expansion of the federal government under Lyndon B Johnson in the 1960s.

| NOTE: The activities below will not be counted towards your final grade for this class. They are strictly here to help you check your knowledge in preparation for class assignments and future dialogue. Best of luck! |

Glossary

- bureaucracy

- an administrative group of nonelected officials charged with carrying out functions connected to a series of policies and programs

- bureaucrats

- the civil servants or political appointees who fill nonelected positions in government and make up the bureaucracy

- civil servants

- the individuals who fill nonelected positions in government and make up the bureaucracy; also known as bureaucrats

- merit system

- a system of filling civil service positions by using competitive examinations to value experience and competence over political loyalties

- patronage

- the use of government positions to reward individuals for their political support

- public administration

- the implementation of public policy as well as the academic study that prepares civil servants to work in government

- spoils system

- a system that rewards political loyalties or party support during elections with bureaucratic appointments after victory

- For general information on ancient bureaucracies see Amanda Summer. 2012. “The Birth of Bureaucracy”. Archaeology 65, No. 4: 33–39; Clyde Curry Smith. 1977. “The Birth of Bureaucracy”. The Bible Archaeologist 40, No. 1: 24–28; Ronald J. Williams. 1972. “Scribal Training in Ancient Egypt,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 92, No. 2: 214–21. ↵

- Richard Stillman. 2009. Public Administration: Concepts and Cases. 9th edition. Boston: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. ↵

- For the early origins of the U.S. bureaucracy see Michael Nelson. 1982. “A Short, Ironic History of American National Bureaucracy,” The Journal of Politics 44 No. 3: 747–78. ↵

- Daniel Walker Howe. 2007. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 334. ↵

- Jack Ladinsky. 1966. “Review of Status and Kinship in the Higher Civil Service: Standards of Selection in the Administrations of John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and Andrew Jackson,” American Sociological Review 31 No. 6: 863–64. ↵

- Jack Rabin and James S. Bowman. 1984. “Politics and Administration: Woodrow Wilson and American Public Administration,” Public Administration and Public Policy; 22: 104. ↵

- For more on President Wilson’s efforts at reform see Kendrick A. Clements. 1998. “Woodrow Wilson and Administrative Reform,” Presidential Studies Quarterly 28 No. 2: 320–36; Larry Walker. 1989. “Woodrow Wilson, Progressive Reform, and Public Administration,” Political Science Quarterly 104, No. 3: 509–25. ↵

- https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/data-analysis-documentation/federal-employment-reports/historical-tables/executive-branch-civilian-employment-since-1940/ (May 15, 2016). ↵

- https://www.opm.gov/policy-data-oversight/data-analysis-documentation/federal-employment-reports/historical-tables/total-government-employment-since-1962 (May 15, 2016). ↵

- For more on LBJ and the Great Society see: John A. Andrew. 1998. Lyndon Johnson and the Great Society. Chicago: Ivan R Dee; Julian E. Zelizer. 2015. The Fierce Urgency of Now: Lyndon Johnson, Congress, and the Battle for the Great Society. New York: Penguin Press. ↵

- John Mikesell. 2014. Fiscal Administration, 9th ed. Boston: Cengage. ↵