Chapter 6: The Politics of Public Opinion

The Effects of Public Opinion

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the circumstances that lead to public opinion affecting policy

- Compare the effects of public opinion on government branches and figures

- Identify situations that cause conflicts in public opinion

Public opinion polling is prevalent even outside election season. Are politicians and leaders listening to these polls, or is there some other reason for them? Some believe the increased collection of public opinion is due to growing support of delegate representation. The theory of delegate representation assumes the politician is in office to be the voice of the people.[1]

If voters want the legislator to vote for legalizing marijuana, for example, the legislator should vote to legalize marijuana. Legislators or candidates who believe in delegate representation may poll the public before an important vote comes up for debate in order to learn what the public desires them to do.

Others believe polling has increased because politicians, like the president, operate in permanent campaign mode. To continue contributing money, supporters must remain happy and convinced the politician is listening to them. Even if the elected official does not act in a manner consistent with the polls, he or she can mollify everyone by explaining the reasons behind the vote.[2]

Regardless of why the polls are taken, studies have not clearly shown whether the branches of government consistently act on them. Some branches appear to pay closer attention to public opinion than other branches, but events, time periods, and politics may change the way an individual or a branch of government ultimately reacts.

PUBLIC OPINION AND ELECTIONS

Elections are the events on which opinion polls have the greatest measured effect. Public opinion polls do more than show how we feel on issues or project who might win an election. The media use public opinion polls to decide which candidates are ahead of the others and therefore of interest to voters and worthy of interview. From the moment President Obama was inaugurated for his second term, speculation began about who would run in the 2016 presidential election. Within a year, potential candidates were being ranked and compared by a number of newspapers.[3]

The speculation included favorability polls on Hillary Clinton, which measured how positively voters felt about her as a candidate. The media deemed these polls important because they showed Clinton as the frontrunner for the Democrats in the next election.[4]

During presidential primary season, we see examples of the bandwagon effect, in which the media pays more attention to candidates who poll well during the fall and the first few primaries. Bill Clinton was nicknamed the “Comeback Kid” in 1992, after he placed second in the New Hampshire primary despite accusations of adultery with Gennifer Flowers. The media’s attention on Clinton gave him the momentum to make it through the rest of the primary season, ultimately winning the Democratic nomination and the presidency.

Polling is also at the heart of horserace coverage, in which, just like an announcer at the racetrack, the media calls out every candidate’s move throughout the presidential campaign. Horserace coverage can be neutral, positive, or negative, depending upon what polls or facts are covered ((Figure)). During the 2012 presidential election, the Pew Research Center found that both Mitt Romney and President Obama received more negative than positive horserace coverage, with Romney’s growing more negative as he fell in the polls.[5]

Horserace coverage is often criticized for its lack of depth; the stories skip over the candidates’ issue positions, voting histories, and other facts that would help voters make an informed decision. Yet, horserace coverage is popular because the public is always interested in who will win, and it often makes up a third or more of news stories about the election.[6]

Exit polls, taken the day of the election, are the last election polls conducted by the media. Announced results of these surveys can deter voters from going to the polls if they believe the election has already been decided.

|

Should Exit Polls Be Banned? Exit polling seems simple. An interviewer stands at a polling place on Election Day and asks people how they voted. But the reality is different. Pollsters must select sites and voters carefully to ensure a representative and random poll. Some people refuse to talk and others may lie. The demographics of the polled population may lean more towards one party than another. Absentee and early voters cannot be polled. Despite these setbacks, exit polls are extremely interesting and controversial, because they provide early information about which candidate is ahead. In 1985, a so-called gentleman’s agreement between the major networks and Congress kept exit poll results from being announced before a state’s polls closed.[7] This tradition has largely been upheld, with most media outlets waiting until 7 p.m. or later to disclose a state’s returns. Internet and cable media, however, have not always kept to the agreement. Sources like Matt Drudge have been accused of reporting early, and sometimes incorrect, exit poll results. On one hand, delaying results may be the right decision. Studies suggest that exit polls can affect voter turnout. Reports of close races may bring additional voters to the polls, whereas apparent landslides may prompt people to stay home. Other studies note that almost anything, including bad weather and lines at polling places, dissuades voters. Ultimately, it appears exit poll reporting affects turnout by up to 5 percent.[8] On the other hand, limiting exit poll results means major media outlets lose out on the chance to share their carefully collected data, leaving small media outlets able to provide less accurate, more impressionistic results. And few states are affected anyway, since the media invest only in those where the election is close. Finally, an increasing number of voters are now voting up to two weeks early, and these numbers are updated daily without controversy. What do you think? Should exit polls be banned? Why or why not? |

Public opinion polls also affect how much money candidates receive in campaign donations. Donors assume public opinion polls are accurate enough to determine who the top two to three primary candidates will be, and they give money to those who do well. Candidates who poll at the bottom will have a hard time collecting donations, increasing the odds that they will continue to do poorly. This was apparent in the run-up to the 2016 presidential election. Bernie Sanders, Hillary Clinton, and Martin O’Malley each campaigned in the hope of becoming the Democratic presidential nominee. In June 2015, 75 percent of Democrats likely to vote in their state primaries said they would vote for Clinton, while 15 percent of those polled said they would vote for Sanders. Only 2 percent said they would vote for O’Malley.[9]

During this same period, Clinton raised $47 million in campaign donations, Sanders raised $15 million, and O’Malley raised $2 million.[10]

By September 2015, 23 percent of likely Democratic voters said they would vote for Sanders,[11] and his summer fundraising total increased accordingly.[12]

Presidents running for reelection also must perform well in public opinion polls, and being in office may not provide an automatic advantage. Americans often think about both the future and the past when they decide which candidate to support.[13]

They have three years of past information about the sitting president, so they can better predict what will happen if the incumbent is reelected. That makes it difficult for the president to mislead the electorate. Voters also want a future that is prosperous. Not only should the economy look good, but citizens want to know they will do well in that economy.[14]

For this reason, daily public approval polls sometimes act as both a referendum of the president and a predictor of success.

PUBLIC OPINION AND GOVERNMENT

The relationship between public opinion polls and government action is murkier than that between polls and elections. Like the news media and campaign staffers, members of the three branches of government are aware of public opinion. But do politicians use public opinion polls to guide their decisions and actions?

The short answer is “sometimes.” The public is not perfectly informed about politics, so politicians realize public opinion may not always be the right choice. Yet many political studies, from the American Voter in the 1920s to the American Voter Revisited in the 2000s, have found that voters behave rationally despite having limited information. Individual citizens do not take the time to become fully informed about all aspects of politics, yet their collective behavior and the opinions they hold as a group make sense. They appear to be informed just enough, using preferences like their political ideology and party membership, to make decisions and hold politicians accountable during an election year.

Overall, the collective public opinion of a country changes over time, even if party membership or ideology does not change dramatically. As James Stimson’s prominent study found, the public’s mood, or collective opinion, can become more or less liberal from decade to decade. While the initial study on public mood revealed that the economy has a profound effect on American opinion,[15] further studies have gone beyond to determine whether public opinion, and its relative liberalness, in turn affect politicians and institutions. This idea does not argue that opinion never affects policy directly, rather that collective opinion also affects the politician’s decisions on policy.[16]

Individually, of course, politicians cannot predict what will happen in the future or who will oppose them in the next few elections. They can look to see where the public is in agreement as a body. If public mood changes, the politicians may change positions to match the public mood. The more savvy politicians look carefully to recognize when shifts occur. When the public is more or less liberal, the politicians may make slight adjustments to their behavior to match. Politicians who frequently seek to win office, like House members, will pay attention to the long- and short-term changes in opinion. By doing this, they will be less likely to lose on Election Day.[17]

Presidents and justices, on the other hand, present a more complex picture.

Public opinion of the president is different from public opinion of Congress. Congress is an institution of 535 members, and opinion polls look at both the institution and its individual members. The president is both a person and the head of an institution. The media pays close attention to any president’s actions, and the public is generally well informed and aware of the office and its current occupant. Perhaps this is why public opinion has an inconsistent effect on presidents’ decisions. As early as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration in the 1930s, presidents have regularly polled the public, and since Richard Nixon’s term (1969–1974), they have admitted to using polling as part of the decision-making process.

Presidential responsiveness to public opinion has been measured in a number of ways, each of which tells us something about the effect of opinion. One study examined whether presidents responded to public opinion by determining how often they wrote amicus briefs and asked the court to affirm or reverse cases. It found that the public’s liberal (or non-liberal) mood had an effect, causing presidents to pursue and file briefs in different cases.[18]

But another author found that the public’s level of liberalness is ignored when conservative presidents, such as Ronald Reagan or George W. Bush, are elected and try to lead. In one example, our five most recent presidents’ moods varied from liberal to non-liberal, while public sentiment stayed consistently liberal.[19]

While the public supported liberal approaches to policy, presidential action varied from liberal to non-liberal.

Overall, it appears that presidents try to move public opinion towards personal positions rather than moving themselves towards the public’s opinion.[20]

If presidents have enough public support, they use their level of public approval indirectly as a way to get their agenda passed. Immediately following Inauguration Day, for example, the president enjoys the highest level of public support for implementing campaign promises. This is especially true if the president has a mandate, which is more than half the popular vote. Barack Obama’s recent 2008 victory was a mandate with 52.9 percent of the popular vote and 67.8 percent of the Electoral College vote.[21]

In contrast, President Donald Trump’s victory over Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton was a closer contest. While Trump finished with a solid lead in the Electoral College, Clinton actually received more votes across the nation, leading the popular vote.

When presidents have high levels of public approval, they are likely to act quickly and try to accomplish personal policy goals. They can use their position and power to focus media attention on an issue. This is sometimes referred to as the bully pulpit approach. The term “bully pulpit” was coined by President Theodore Roosevelt, who believed the presidency commanded the attention of the media and could be used to appeal directly to the people. Roosevelt used his position to convince voters to pressure Congress to pass laws.

Increasing partisanship has made it more difficult for presidents to use their power to get their own preferred issues through Congress, however, especially when the president’s party is in the minority in Congress.[22]

For this reason, modern presidents may find more success in using their popularity to increase media and social media attention on an issue. Even if the president is not the reason for congressional action, he or she can cause the attention that leads to change.[23]

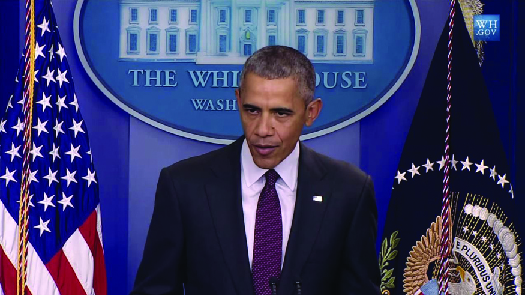

Presidents may also use their popularity to ask the people to act. In October 2015, following a shooting at Umpqua Community College in Oregon, President Obama gave a short speech from the West Wing of the White House ((Figure)). After offering his condolences and prayers to the community, he remarked that prayers and condolences were no longer enough, and he called on citizens to push Congress for a change in gun control laws. President Obama had proposed gun control reform following the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary in Connecticut, but it did not pass Congress. This time, the president asked citizens to use gun control as a voting issue and push for reform via the ballot box.

Figure 2. In the wake of a shooting at Umpqua Community College in Oregon in October 2015, President Obama called for a change in gun control laws (credit: The White House).

In some instances, presidents may appear to directly consider public opinion before acting or making decisions. In 2013, President Obama announced that he was considering a military strike on Syria in reaction to the Syrian government’s illegal use of sarin gas on its own citizens. Despite agreeing that this chemical attack on the Damascan suburbs was a war crime, the public was against U.S. involvement. Forty-eight percent of respondents said they opposed airstrikes, and only 29 percent were in favor. Democrats were especially opposed to military intervention.[24]

President Obama changed his mind and ultimately allowed Russian president Vladimir Putin to negotiate Syria’s surrender of its chemical weapons.

However, further examples show that presidents do not consistently listen to public opinion. After taking office in 2009, President Obama did not order the closing of Guantanamo Bay prison, even though his proposal to do so had garnered support during the 2008 election. President Bush, despite growing public disapproval for the war in Iraq, did not end military support in Iraq after 2006. And President Bill Clinton, whose White House pollsters were infamous for polling on everything, sometimes ignored the public if circumstances warranted.[25]

In 1995, despite public opposition, Clinton guaranteed loans for the Mexican government to help the country out of financial insolvency. He followed this decision with many speeches to help the American public understand the importance of stabilizing Mexico’s economy. Individual examples like these make it difficult to persuasively identify the direct effects of public opinion on the presidency.

While presidents have at most only two terms to serve and work, members of Congress can serve as long as the public returns them to office. We might think that for this reason public opinion is important to representatives and senators, and that their behavior, such as their votes on domestic programs or funding, will change to match the expectation of the public. In a more liberal time, the public may expect to see more social programs. In a non-liberal time, the public mood may favor austerity, or decreased government spending on programs. Failure to recognize shifts in public opinion may lead to a politician’s losing the next election.[26]

House of Representatives members, with a two-year term, have a more difficult time recovering from decisions that anger local voters. And because most representatives continually fundraise, unpopular decisions can hurt their campaign donations. For these reasons, it seems representatives should be susceptible to polling pressure. Yet one study, by James Stimson, found that the public mood does not directly affect elections, and shifts in public opinion do not predict whether a House member will win or lose. These elections are affected by the president on the ticket, presidential popularity (or lack thereof) during a midterm election, and the perks of incumbency, such as name recognition and media coverage. In fact, a later study confirmed that the incumbency effect is highly predictive of a win, and public opinion is not.[27]

In spite of this, we still see policy shifts in Congress, often matching the policy preferences of the public. When the shifts happen within the House, they are measured by the way members vote. The study’s authors hypothesize that House members alter their votes to match the public mood, perhaps in an effort to strengthen their electoral chances.[28]

The Senate is quite different from the House. Senators do not enjoy the same benefits of incumbency, and they win reelection at lower rates than House members. Yet, they do have one advantage over their colleagues in the House: Senators hold six-year terms, which gives them time to engage in fence-mending to repair the damage from unpopular decisions. In the Senate, Stimson’s study confirmed that opinion affects a senator’s chances at reelection, even though it did not affect House members. Specifically, the study shows that when public opinion shifts, fewer senators win reelection. Thus, when the public as a whole becomes more or less liberal, new senators are elected. Rather than the senators shifting their policy preferences and voting differently, it is the new senators who change the policy direction of the Senate.[29]

Beyond voter polls, congressional representatives are also very interested in polls that reveal the wishes of interest groups and businesses. If AARP, one of the largest and most active groups of voters in the United States, is unhappy with a bill, members of the relevant congressional committees will take that response into consideration. If the pharmaceutical or oil industry is unhappy with a new patent or tax policy, its members’ opinions will have some effect on representatives’ decisions, since these industries contribute heavily to election campaigns.

There is some disagreement about whether the Supreme Court follows public opinion or shapes it. The lifetime tenure the justices enjoy was designed to remove everyday politics from their decisions, protect them from swings in political partisanship, and allow them to choose whether and when to listen to public opinion. More often than not, the public is unaware of the Supreme Court’s decisions and opinions. When the justices accept controversial cases, the media tune in and ask questions, raising public awareness and affecting opinion. But do the justices pay attention to the polls when they make decisions?

Studies that look at the connection between the Supreme Court and public opinion are contradictory. Early on, it was believed that justices were like other citizens: individuals with attitudes and beliefs who would be affected by political shifts.[30]

Later studies argued that Supreme Court justices rule in ways that maintain support for the institution. Instead of looking at the short term and making decisions day to day, justices are strategic in their planning and make decisions for the long term.[31]

Other studies have revealed a more complex relationship between public opinion and judicial decisions, largely due to the difficulty of measuring where the effect can be seen. Some studies look at the number of reversals taken by the Supreme Court, which are decisions with which the Court overturns the decision of a lower court. In one study, the authors found that public opinion slightly affects cases accepted by the justices.[32]

In a study looking at how often the justices voted liberally on a decision, a stronger effect of public opinion was revealed.[33]

Whether the case or court is currently in the news may also matter. A study found that if the majority of Americans agree on a policy or issue before the court, the court’s decision is likely to agree with public opinion.[34]

A second study determined that public opinion is more likely to affect ignored cases than heavily reported ones.[35]

In these situations, the court was also more likely to rule with the majority opinion than against it. For example, in Town of Greece v. Galloway (2014), a majority of the justices decided that ceremonial prayer before a town meeting was not a violation of the Establishment Clause.[36]

The fact that 78 percent of U.S. adults recently said religion is fairly to very important to their lives[37] and 61 percent supported prayer in school[38] may explain why public support for the Supreme Court did not fall after this decision.[39]

Overall, however, it is clear that public opinion has a less powerful effect on the courts than on the other branches and on politicians.[40]

Perhaps this is due to the lack of elections or justices’ lifetime tenure, or perhaps we have not determined the best way to measure the effects of public opinion on the Court.

Summary

Public opinion polls have some effect on politics, most strongly during election season. Candidates who do well in polls receive more media coverage and campaign donations than candidates who fare poorly. The effect of polling on government institutions is less clear. Presidents sometimes consider polls when making decisions, especially if the polls reflect high approval. A president who has an electoral mandate can use that high public approval rating to push policies through Congress. Congress is likely to be aware of public opinion on issues. Representatives must continually raise campaign donations for bi-yearly elections. For this reason, they must keep their constituents and donors happy. Representatives are also likely to change their voting behavior if public opinion changes. Senators have a longer span between elections, which gives them time to make decisions independent of opinion and then make amends with their constituents. Changes in public opinion do not affect senators’ votes, but they do cause senators to lose reelection. It is less clear whether Supreme Court justices rule in ways that maintain the integrity of the branch or that keep step with the majority opinion of the public, but public approval of the court can change after high-profile decisions.

| NOTE: The activities below will not be counted towards your final grade for this class. They are strictly here to help you check your knowledge in preparation for class assignments and future dialogue. Best of luck! |

Suggested ReadingAlvarez, Michael, and John Brehm. 2002. Hard Choices, Easy Answers: Values, Information and American Public Opinion. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Campbell, Angus, Philip Converse, Warren Miller, and Donald Stokes. 1980. The American Voter: Unabridged Edition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Canes-Wrone, Brandice. 2005. Who Leads Whom? Presidents, Policy and the Public. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Downs, Anthony. 1957. An Economic Theory of Democracy. New York: Harper. Lewis-Beck, Michael S., Helmut Norpoth, William Jacoby, and Herbert Weisberg. 2008. The American Voter Revisited. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Lippmann, Walter. 1922. Public Opinion. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co. Lupia, Arthur, and Mathew McCubbins. 1998. The Democratic Dilemma. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pew Research Center (http://www.pewresearch.org/). Real Clear Politics’ Polling Center (http://www.realclearpolitics.com/epolls/latest_polls/). Zaller, John. 1992. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

Glossary

- bandwagon effect

- increased media coverage of candidates who poll high

- favorability poll

- a public opinion poll that measures a public’s positive feelings about a candidate or politician

- horserace coverage

- day-to-day media coverage of candidate performance in the election

- theory of delegate representation

- a theory that assumes the politician is in office to be the voice of the people and to vote only as the people want

- Donald Mccrone, and James Kuklinski. 1979. “The Delegate Theory of Representation.” American Journal of Political Science 23 (2): 278–300. ↵

- Norman Ornstein, and Thomas Mann, eds. 2000. The Permanent Campaign and Its Future. Washington: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research and the Brookings Institution. ↵

- Paul Hitlin. 2013. “The 2016 Presidential Media Primary Is Off to a Fast Start.” Pew Research Center. October 3, 2013. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/10/03/the-2016-presidential-media-primary-is-off-to-a-fast-start/ (February 18, 2016). ↵

- Pew Research Center, 2015. “Hillary Clinton’s Favorability Ratings over Her Career.” Pew Research Center. June 6, 2015. http://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/themes/pewresearch/static/hillary-clintons-favorability-ratings-over-her-career/ (February 18, 2016). ↵

- Pew Research Center. 2012. “Winning the Media Campaign.” Pew Research Center. November 2, 2012. http://www.journalism.org/2012/11/02/winning-media-campaign-2012/ (February 18, 2016). ↵

- Pew Research Center. 2012. “Fewer Horserace Stories-and Fewer Positive Obama Stories-Than in 2008.” Pew Research Center. November 2, 2012. http://www.journalism.org/2012/11/01/press-release-6/ (February 18, 2016). ↵

- Zack Nauth, “Networks Won’t Use Exit Polls in State Forecasts,” Los Angeles Times, 18 January 1985. ↵

- Seymour Sudman. 1986. “Do Exit Polls Influence Voting Behavior? The Public Opinion Quarterly 50 (3): 331–339. ↵

- Patrick O’Connor. 2015. “WSJ/NBC Poll Finds Hillary Clinton in a Strong Position.” Wall Street Journal. June 23, 2015. http://www.wsj.com/articles/new-poll-finds-hillary-clinton-tops-gop-presidential-rivals-1435012049. ↵

- Federal Elections Commission. 2015. “Presidential Receipts.” http://www.fec.gov/press/summaries/2016/tables/presidential/presreceipts_2015_q2.pdf (February 18, 2016). ↵

- Susan Page and Paulina Firozi, “Poll: Hillary Clinton Still Leads Sanders and Biden But By Less,” USA Today, 1 October 2015. ↵

- Dan Merica, and Jeff Zeleny. 2015. “Bernie Sanders Nearly Outraises Clinton, Each Post More Than $20 Million.” CNN. October 1, 2015. http://www.cnn.com/2015/09/30/politics/bernie-sanders-hillary-clinton-fundraising/index.html?eref=rss_politics (February 18, 2016). ↵

- Robert S. Erikson, Michael B. MacKuen, and James A. Stimson. 2000. “Bankers or Peasants Revisited: Economic Expectations and Presidential Approval.” Electoral Studies 19: 295–312. ↵

- Erikson et al, “Bankers or Peasants Revisited: Economic Expectations and Presidential Approval. ↵

- Michael B. MacKuen, Robert S. Erikson, and James A. Stimson. 1989. “Macropartisanship.” American Political Science Review 83 (4): 1125–1142. ↵

- James A. Stimson, Michael B. Mackuen, and Robert S. Erikson. 1995. “Dynamic Representation.” American Political Science Review 89 (3): 543–565. ↵

- Stimson et al, “Dynamic Representation.” ↵

- Stimson et al, “Dynamic Representation.” ↵

- Dan Wood. 2009. Myth of Presidential Representation. New York: Cambridge University Press, 96-97. ↵

- Wood, Myth of Presidential Representation. ↵

- U.S. Election Atlas. 2015. “United States Presidential Election Results.” U.S. Election Atlas. June 22, 2015. http://uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/ (February 18, 2016). ↵

- Richard Fleisher, and Jon R. Bond. 1996. “The President in a More Partisan Legislative Arena.” Political Research Quarterly 49 no. 4 (1996): 729–748. ↵

- George C. Edwards III, and B. Dan Wood. 1999. “Who Influences Whom? The President, Congress, and the Media.” American Political Science Review 93 (2): 327–344. ↵

- Pew Research Center. 2013. “Public Opinion Runs Against Syrian Airstrikes.” Pew Research Center. September 4, 2013. http://www.people-press.org/2013/09/03/public-opinion-runs-against-syrian-airstrikes/ (February 18, 2016). ↵

- Paul Bedard. 2013. “Poll-Crazed Clinton Even Polled on His Dog’s Name.” Washington Examiner. April 30, 2013. http://www.washingtonexaminer.com/poll-crazed-bill-clinton-even-polled-on-his-dogs-name/article/2528486. ↵

- Stimson et al, “Dynamic Representation.” ↵

- Suzanna De Boef, and James A. Stimson. 1995. “The Dynamic Structure of Congressional Elections.” Journal of Politics 57 (3): 630–648. ↵

- Stimson et al, “Dynamic Representation.” ↵

- Stimson et al, “Dynamic Representation.” ↵

- Benjamin Cardozo. 1921. The Nature of the Judicial Process. New Haven: Yale University Press. ↵

- Jack Knight, and Lee Epstein. 1998. The Choices Justices Make. Washington DC: CQ Press. ↵

- Kevin T. Mcguire, Georg Vanberg, Charles E Smith, and Gregory A. Caldeira. 2009. “Measuring Policy Content on the U.S. Supreme Court.” Journal of Politics 71 (4): 1305–1321. ↵

- Kevin T. McGuire, and James A. Stimson. 2004. “The Least Dangerous Branch Revisited: New Evidence on Supreme Court Responsiveness to Public Preferences.” Journal of Politics 66 (4): 1018–1035. ↵

- Thomas Marshall. 1989. Public Opinion and the Supreme Court. Boston: Unwin Hyman. ↵

- Christopher J. Casillas, Peter K. Enns, and Patrick C. Wohlfarth. 2011. “How Public Opinion Constrains the U.S. Supreme Court.” American Journal of Political Science 55 (1): 74–88. ↵

- Town of Greece v. Galloway 572 U.S. ___ (2014). ↵

- Gallup. 2015. “Religion.” Gallup. June 18, 2015. http://www.gallup.com/poll/1690/Religion.aspx (February 18, 2016). ↵

- Rebecca Riffkin. 2015. “In U.S., Support for Daily Prayer in Schools Dips Slightly.” Gallup. September 25, 2015. http://www.gallup.com/poll/177401/support-daily-prayer-schools-dips-slightly.aspx. ↵

- Gallup. 2015. “Supreme Court.” Gallup. http://www.gallup.com/poll/4732/supreme-court.aspx (February 18, 2016). ↵

- Stimson et al, “Dynamic Representation.” ↵