Writer’s Block

Barry Mauer and John Venecek

We discuss the following topic on this page:

We provide the following activity:

Common Obstacles and Suggested Ways to Deal with Them

Common Obstacles and Suggested Ways to Deal with Them

Just about every writer experiences obstacles in their writing. When these obstacles become very problematic and we are unable to write, we refer to the condition as writer’s block. The “block” means that something stands between the writer and the task. It may be frustrating but it can be productive if you work through it. Overcoming writer’s block strengthens your ability to solve problems and become a better writer.

A block can be internal, such as psychological resistance. If so, find out why it’s coming up. If it’s external, it’s an opportunity to change your circumstances or your priorities. If it’s about the research project itself, it’s an opportunity to address complexities or rethink the research problem or your approach.

Example: Common Obstacles and Suggested Ways to Deal with Them

Example: Common Obstacles and Suggested Ways to Deal with Them

- Bad writing (shapeless or meandering prose). Advice: find a scholar whose work you really admire. Try to write in the style of that person or examine the structure of their work and see if you can structure yours in a similar way. For example, maybe the text you admire is structured as a comparison/contrast. See if that structure works for your project. Ask for feedback and advice from more advanced researchers and writers.

- Blocked access to research materials. Advice: prepare in advance so you are not without your research materials. If you are working with digital materials, carry them with you on a storage device such as a flash drive or in cloud storage. If you need access to printed library materials, make sure you look them up in the online catalog first to see if they are available. Schedule a time to go to the library and scan/photograph shorter works or excerpts and store those on an electronic device or in cloud storage.

- Busyness. Advice: commit to a schedule. Do your research and writing on a regular basis (like three times a week). Start the work session by setting a timer and work for 15 minutes without a break. When the time is up, see if you can keep going. Make sure you take an actual break and walk around at least once an hour. If there seems to be too many activities in your life that are overlapping (i.e., social gatherings and research time), buy a planner or use your phone’s calendar with audio reminders to help you commit to your schedule. If all else fails, you may need to choose one activity over the other.

- Depression/Anxiety. Advice: prioritize self-care, such as proper eating, sleep, and exercise. Let go of toxic relationships. Get help from professionals if needed. Think of writing as a meaningful activity that actually helps many people overcome their psychological pressures. If you need additional help from UCF, please visit CAPS (Counseling and Psychological Services).

- Distraction. Advice: shut down other things, like video games, web browsers, music, and text messaging. If you care about your success as a student, you will prioritize your research over distractions.

- Exhaustion. Advice: get an early start if possible and go at a steady pace. If you try to do too much too fast, you’ll get burn out.

- Family and work responsibilities. Advice: you may need to change your work schedule, find childcare, etc. The realities of life can make being a successful researcher difficult. Make adjustments as you can.

- Fear of being wrong. Advice: do your research and writing in good faith (by trying not to deceive yourself or others) and if you later discover you were wrong about something, you can produce another piece of writing explaining how your views evolved. We likely will be wrong in our writing from time to time.

- Fear of controversy. Advice: if your methods or argument are likely to be controversial, be prepared to defend and justify them in your writing. If you can strongly defend these things, then controversy itself is not a sufficient reason to stop a research project.

- Getting started. Advice: put words on paper (or on screen). Lots of people have difficulty taking the first step on a research project. Motivate yourself by using fun activities to reward yourself after you’ve done some research and writing. Starting is the most important thing, so don’t worry if your first words on paper or screen are bad. Use accountability partners; take turns reading each other’s work every few days.

- Getting stuck in the middle. Advice: list the remaining tasks. Do the critical tasks first. Be willing to change to a different part of the research or writing project. Think about your various projects the way a chef does; some things are on the front burners and some things on the back burners. When one project needs to rest, put it on the back burner and work on something else.

- Language fluency. Advice: plan extra time for your work. If you are reading and writing in a language that you don’t feel fully fluent in, try writing your main ideas in your first language and then work on translating them.

- Negative self-assessment. Advice: get support from other people. Our self-talk can get negative and tell us we are not smart enough or not capable enough. Other people can see our intelligence and our capabilities even when we can’t. Have them tell you about yours!

- Not in the mood. Advice: don’t allow yourself to get too fussy about your environment. Some people need a specific set of conditions to do their research and writing: a cup of coffee, a quiet room, and a soft cat. These are all fine, but the best way to get in the mood to write is to start writing.

- Other priorities. Advice: prioritize things by deadlines and that are most valuable to your career (i.e., prioritize work on high value assignments). If other things are left unfinished temporarily, that’s ok.

- Panic. Advice: plan far ahead and scheduling tasks on various projects. If it gets to be close to the deadline and you still have too many projects due, prioritize the ones that are most important, take the loss (you’ll probably have more opportunities in the future), and let go of the panic.

- Slow pace of writing. Advice: keep making progress. Are you making measurable progress? Then you are doing well. Some research and writing tasks take longer than others. If you are stuck in the weeds (getting obsessive about details), go back to the big picture.

- Too much research. Advice: know when enough research is enough. Researchers rarely have the luxury to gather all the available knowledge about a topic (a maximizing strategy called “coverage”). Sometimes researchers feel they must keep going until they understand what everyone has ever said about a topic. We have to accept that uncertainty is part of the process and make the project as good as we can (a strategy called “optimizing”) or, if we need to move on, make it good enough (a strategy called “satisficing).”

- Uncertainty. Advice: approach complicated issues in your project systematically. Sometimes writers are overwhelmed with the complexity of the task before them. Write down a list of the complications in your project and address them one at a time.

- “What I have so far is terrible!” Advice: take what you have and see how it can be better. Then do it again. Research and writing are about improvement. Making steady improvements is a process called hill climbing. Eventually you will be high enough on the hill that you can see above the clouds. Judging your work as terrible is part of “Negative Self-Talk.” Your project is probably not as bad as what your inner-voice is telling you. Don’t think of what you have written as “terrible”; focus on the good parts of your writing!

All writers want the muse to carry them across the finish line. The truth is that most good writing requires more perspiration than inspiration; inspiration occurs because we created the conditions for it with our perspiration. Keep at it. Inspiration may or may not come. Your writing will improve as you practice and learn.

For additional help with your writing, visit these pages from WritingCommons.org:

- Mindset

- Growth Mindset

- Faith in the Writing Process

- The Believing Game

- Why Write

- Effective Writing Habits

- Intellectual Openness

- Demystify Writing Misconceptions

- Self-Regulation & Metacognition

- Establish a Comfortable Place to Write

- Overcome Discouragement

- Reflect on Your Writing Processes

- Scheduling Writing

- Resilience

Purdue Online Writing Lab also has great resources:

Writer’s Block [Refresher]

Writer’s Block [Refresher]

If you are using an offline version of this text, access the quiz for this section via the QR code.

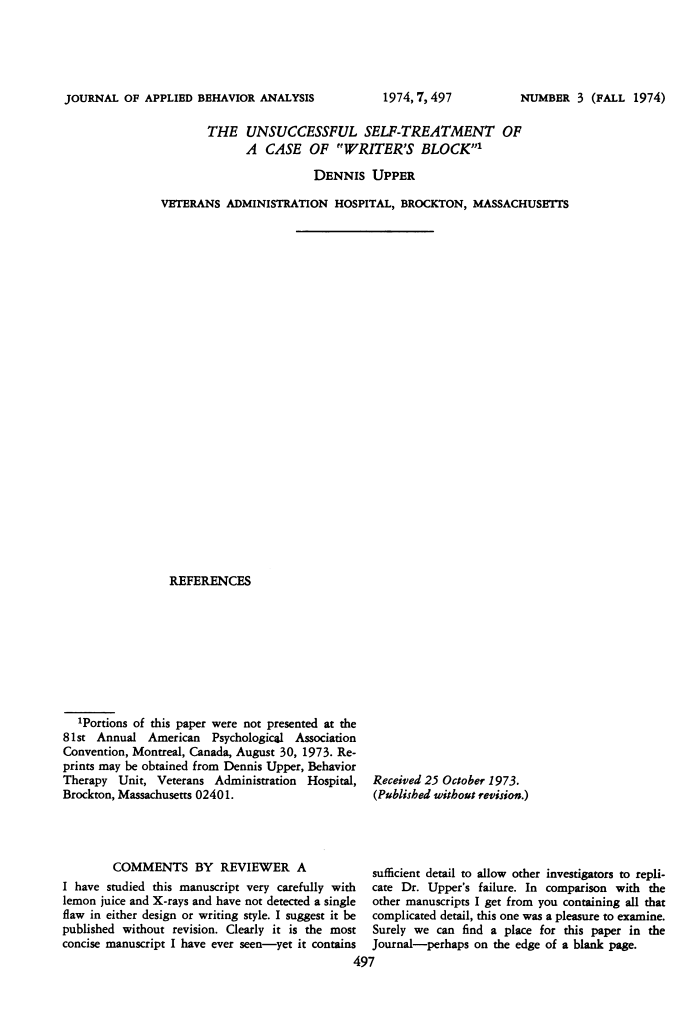

- Dennis Upper's famous case of writer's block. See this US National Library of Medicine/National Institutes of Health page for further information. ↵