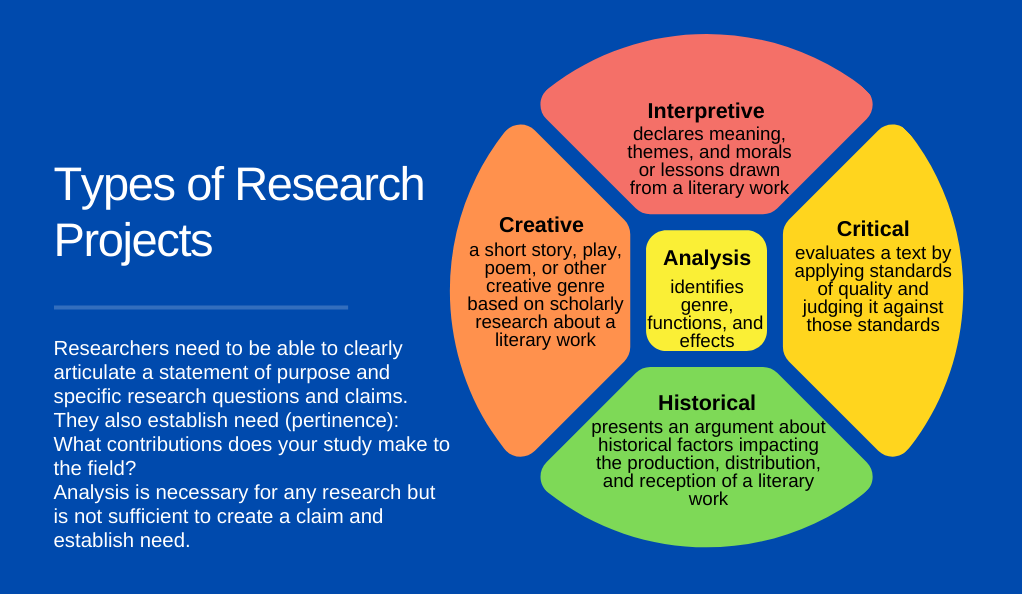

Types of Research Projects

Barry Mauer and John Venecek

We describe four types of research projects on this page:

We also provide the following activities:

Your instructor may ask you to produce only one specific type, or allow you to choose among several. Please consult with your instructor if you are unsure what kind of project is acceptable.

Introduction

Introduction

Researchers begin each project by considering the following questions:

- What is the purpose of my research?

- What are the specific hypotheses (claims) or research questions that my work explores?

- What pertinence does my research have for others? Another way of posing the question is to ask: what contributions does my proposed study make to the field? This question is often answered by providing a review of existing scholarly literature and then demonstrating how your work fills a gap or in other ways clarifies or extends the work of others.

Research projects also include the following elements:

- A specific description of the problem or topic being studied, and a summary of the argument and its supporting elements, including any necessary definitions.

- A statement of the significance of the problem or topic.

- A review of the scholarly literature on the topic.

- An explanation of the methodology and theoretical approach of the study, describing what information is used, how it is applied to the topic of study, and why the methodology and theoretical approach were chosen.

- A list of works cited and annotated (annotated bibliography) that provides complete information for each reference mentioned in the literature review.

Research projects are interrogative, meaning that they develop out of questions. The researcher engages with the materials (the literary text, primary and secondary sources, etc.) and asks questions about them such as whether X is true, what X means, whether X is good or relevant, etc. The answers lead to another set of questions and so on and on. Research projects are also imaginative, meaning that the researcher wishes to make a certain kind of project and labors to develop it. Imaginative thinking requires “what if” questions. What if we perceive a literary text from another perspective? What if we focus on a secondary character? What if we use a new research method?

Interpretive Research Projects

Interpretive Research Projects

An interpretive research project declares:

- what a text means,

- what its major themes are, and

- what morals or lessons the reader should draw from it.

Example [Interpretive]

Example [Interpretive]

An example of an interpretive claim is found in Frank Kermode’s interpretation of Jesus’ parable about the Sower of Seeds:

“For to him who has will more be given; and from him who has not, even what he has will be taken away.” To divine the true, the latent sense, you need to be of the elect, of the institution. Outsiders must content themselves with the manifest, and pay a supreme penalty for doing so. Only those who already know the mysteries—what the stories really mean—can discover what the stories really mean. (2-3)

Note that Kermode’s interpretation of Jesus’ parable is in conflict with other potential interpretations such as the claim that Jesus meant for his message to be heard and understood by everyone.[1]

For more information about interpretive research projects, read “Interpreting Literary Works” in Chapter 5.

Critical Research Projects

Critical Research Projects

A critical research project:

- evaluates a text by applying standards of quality to the work, and

- judges it against those standards.

Example [Critical]

Example [Critical]

An example of a critical research project is found in Edward Said’s Culture and Imperialism. In Said’s reading of the novel Heart of Darkness, by Joseph Conrad, he sees Conrad as criticizing imperialism, but failing to call for its end. Said writes:

But Marlow and Kurtz are also creatures of their time and cannot take the next step, which would be to recognise that what they saw, disablingly and disparagingly, as a non-European ‘darkness’ was in fact a non-European world resisting imperialism so as one day to regain sovereignty and independence, and not, as Conrad reductively says, to reestablish the darkness. Conrad’s tragic limitation is that even though he could see clearly that on one level imperialism was essentially pure dominance and land-grabbing, he could not then conclude that imperialism had to end so that ‘natives’ could lead lives free from European domination. As a creature of his time, Conrad could not grant the natives their freedom, despite his severe critique of the imperialism that enslaved them. (30)[2]

Though Said recognizes that Conrad was a product of his time (the novel was published in 1899), he praises Conrad for his insights while criticizing him for his limitations. Said’s criticism depends on a series of propositions about what counts as “good” literature about imperialism. We might summarize Said’s propositions this way:

- Literature about imperialism should identify imperialism as domination, violence, and slavery.

- Literature about imperialism should recognize that native efforts to preserve their identities is resistance.

- Literature about imperialism should call for an end to imperialism.

Heart of Darkness meets the first criteria but not the last two. We might disagree with Said’s criteria, but if so, we should be prepared to say what other criteria should be used. Note that Said is not criticizing the quality of the prose (he praises it). His primary concern is whether the literature supports or opposes imperialism.

For more information about critical research projects, read “Critiquing Literary Works” in Chapter 5.

Historical Research Projects

Historical Research Projects

A historical research project presents an argument about:

- historical factors impacting the production, distribution, and reception of a literary work, and

- defining an object of study and a purpose, then collecting, reading, and analyzing your source materials.

The reading should be both wide-ranging and intensive, and your critical judgment is required in the process. The way to maintain focus is to keep in mind the purpose of your study and the questions that you seek to answer. Your bibliography should include all the works referenced in your thesis.

Example [Historical]

Example [Historical]

An example of a historical research project can be found below in a paper by Maddison McGann, who argues that serialization — the publication of novels in installments in periodicals — changed the relationship among authors, readers, and critics.

The fact that critics like Poe were writing and publishing ‘alternative endings’ at the same time as they were reading the novel suggests that reading a serial novel in the mid-nineteenth century was neither a predetermined nor a passive experience; rather, it was a “choose your own adventure” game that allowed for unspoken collaboration to take place between authors and readers. The serial novel (and its subsequent shift in reviewing) enabled readers to become creators as well as consumers, thus changing the way that novels were read and received in mid-nineteenth-century Britain. (79)[3]

McGann’s research explores the real historical events upon which Dickens based his novel, Dickens’ production of the novel in serial form, and its reception by literary critics of his time such as the scathing reviews of Dickens’ work penned by Edgar Allen Poe.

Creative Research Projects

Creative Research Projects

The idea for a creative research project, such as a short story, play, poem, or other creative text based on scholarly research about a literary work, must be determined in consultation with the professor. However, for acceptance, a creative project must include at least the following elements:

- An explanation of why the specific form and genre were selected.

- A bibliography of all references used in the development of the creative thesis.

- A clear description of the nature, scope, and substance of the final creative product. For example, a dramatic adaptation that takes an alternate view of events.

- A discussion of the major elements of the craft used and how they will achieve certain aims or effects.

A creative research project has interrogatory components, which means that the researcher still asks critical questions and pursues answers to them, but creative research projects privilege invention over critique. In other words, the researcher must craft a response that goes beyond the traditional essay and does more “showing” than “telling.”

Example [Creative]

Example [Creative]

An example of a creative research project is Connie Porter’s “Rapunzel across Time and Space.”

Maybe, once upon a time, the moon did show her other face, proudly, boldly, for just one night. It shone down on Earth below just as the other side does, bathed in silver light, brilliant in its fullness. But this face was dismissed for being what it was not—just like the other side. Since that night the moon turned that face forevermore into the darkness of space refusing to let anyone on Earth see it and was called fickle. She was hurt by being made fun of, for being called fickle and sang out her sorrow from the dark side of her face. People hear her voice on windless nights. Part of a chorus people used to call the music of the spheres. Its beauty haunts us, draws us to look up into the sky at night.

We want to hear her voice more clearly, but the moon will never turn its other face to us again. We will have to cross time and space to pull ourselves into her life, make a ladder of our own hair. Nappy. Curly. Straight. Braided. Dreaded. We will have to shave our own heads, all of us become baldheaded and beautiful, weaving a ladder that stretches to her to hear the full beauty of her voice, to see the beauty of the face cloaked in darkness. We will feel the power of her tears as they fall into our eyes. Though not blind, we will see that she was never the one who was fickle. We were. Then we will all live happily ever after. End of story. (282)[4]

In her work, Porter — a black female author — writes about an event in which she heard one of her readers use the word “baldheaded” to insult one of Porter’s fictional characters, a young black girl with short hair. The insult inspired Porter to rethink the familiar Rapunzel tale to see what it teaches us about hair, beauty, gender, and race. In re-reading “Rapunzel,” Porter discovered that the prince is attracted not to Rapunzel’s hair but to her voice. Her hair is merely a means to an end: a rope for him to climb. Porter’s work is a creative hybrid; she reworks the “Rapunzel” story into something that is part personal essay, part literary research, and part polemic. She argues that we should encourage black girls to speak and that we should listen to them and appreciate their voices. By retelling the story, Porter does more than just tell us an argument about “Rapunzel”; she shows us what she learned about it and what it means to her.

Suggested guidelines when doing a creative research project:

- The introduction should discuss the literary theory or theories you are using, how you used them to read the literary work, and what your creative project is in relation to your research question.

- The creative project is part of your research method in that it helps you answer your research question. For instance, let’s say we were wondering what impact gender has in the “Sleeping Beauty” stories by the Brothers Grimm. One way to find out might be to switch the genders of the main characters and see what results.

- The conclusion explains what you discovered or what resulted from the creative work.

Read Chapter 4 for more information about literary theories and methods.

Types of Research Projects [Refresher]

Types of Research Projects [Refresher]

If you are using an offline version of this text, access the quiz for this section via the QR code.

Exercises [Discussion]

Exercises [Discussion]

- Does your assignment allow you to choose the type of research project you’re creating? Get clarification if necessary.

- Which type of research project most appeals to you and why?

- What are your thoughts about using analysis and going beyond it to make a claim and establish need?

- What was the most important lesson you learned from this page? What point was confusing or difficult to understand?

- Kermode, Frank. The Genesis of Secrecy: On the Interpretation of Narrative, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1979. ↵

- Said, Edward W., and Said, Edward William. Culture and imperialism. United Kingdom, Vintage Books, 1994. ↵

- McGann, Maddison. "The Meaning of Prophets and the Making of Trolls: 19th-Century Reception of Charles Dickens’ Barnaby Rudge." Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies 20 (2020): 72-79. ↵

- Porter, Connie. “Rapunzel across Time and Space.” Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: Women Writers Explore Their Favorite Fairy Tale. Kate Bernheimer, ed., pp. 273–282. New York: Anchor, 1998 ↵

Posing and answering questions