Interpreting Literary Works

Barry Mauer and John Venecek

We discuss the following topics on this page:

- Interpretation Introduction

- Discourses

- How to Interpret Literary Texts Using Schemata

- Symptomatic and Explicatory Interpretations

- Steps to Interpretation

We also provide the following activities:

Interpretation Introduction[1]

Interpretation Introduction[1]

Interpretation is the process of making meaning from a text. Literary theorists have different understandings of what meaning is, what constitutes a “good” interpretation, and whether we should even be interpreting literary texts at all. Frank Kermode, for example, claimed that the only people who are able to interpret stories properly are insiders, but even the most knowledgeable insiders – such as Jesus’ disciples – are prone to errors (Jesus had to explain his parables to the disciples because they needed his help). Susan Sontag argued that we should refrain from interpretation and confront the literary and artistic work “as is” so we can experience it on its own terms and not as a different thing (such as an explanation). Umberto Eco stated that literature allows for a range of interpretations but that some interpretations are better than others (though we need to establish standards to assess the quality of different interpretations).

Disagreements about interpretation focus mainly on the reader’s limits. Should the reader be able to make any meaning whatsoever from a text? Does the text resist interpretation and insist on being read on its own terms? What constrains the reader’s freedom to interpret? Do constraints arise from the author, from within the text itself, from within the reader, or from within the culture? Whose culture, we might also ask, should determine the proper interpretation: the reader’s, the author’s, or someone else’s?

Interpretation is a process of gathering evidence (from within the literary text) and making reasoned inferences from that evidence. Our goal when interpreting a text is to offer a better interpretation than the others available. A better interpretation is one that meets particular criteria, though we have to justify and explain why we chose those criteria and not others. Because it it is possible to overlook evidence, misread evidence, etc., we can say that an interpretation that makes good use of evidence is likely better than one that does not. We can also say that a better interpretation will provide a coherent conceptual framework with which to understand a literary text. A better interpretation might account for possible counter-arguments and make a compelling case against each of them.

A better interpretation is also one that is free from reasoning errors. For example, if someone says 2+3+4 = 5, we can say that their chain of reasoning is flawed. Since it is possible to make reasoning errors, we can likely conclude that an interpretation that includes fewer errors in reasoning is better than an interpretation that has serious errors in reasoning. A better interpretation is likely one that produces a greater quantity and quality of meaning than a competing interpretation. Therefore, some interpretations are better than others because they make better use of evidence and reasoning, provide clear conceptual frameworks, and demonstrate advantages over weaker interpretations. Good interpretations give us insight.

Interpretation of a Literary Text

Interpretation of a Literary Text

“Departures”[2]

Storm Jameson

The September day we left for London was cold and cloudily sunny. In the few minutes as the train drew out past the harbour, I felt myself isolated by a barrier of ice from every living human being, including the husband facing me. Like a knot of adders uncoiling themselves one departure slid from another behind my eyes—journeys made feverish by unmanageable longings and ambitions, night journeys in wartime, the darkened corridors crammed with young men in clumsy khaki, smoking, falling asleep, journeys with a heavy baby in one arm. At last I come to the child sitting in a corner of a third-class carriage, waiting, silent, tense with anxiety, for the captain’s wife to return from the ticket office. A bearded gentleman in a frock coat—the stationmaster—saunters up to the open door and says, smiling, something she makes no attempt to hear. Her mother walks lightly across the platform. “Ah, there you are, Mrs. Jameson. Your little girl was afraid you weren’t coming,” he said amiably. Nothing less amiable than Mrs. Jameson’s coldly blue eyes turned on him, and cold voice.

“Nonsense. My child is never afraid.”

Not true . . .

Note contextual facts about the story before doing an interpretation. Scholes, Comley, and Ulmer[3] provide us with the following information:

This selection is the conclusion of a chapter from Margaret Storm Jameson’s autobiography, Journey from the North [1969]. In it she begins to tell of a train journey from Yorkshire (in the north of England) to London made with her husband during World War I. But, in the telling, her mind moves back through memories of other departures to an anecdote of an earlier departure from Yorkshire, this one with her mother (the wife of a sea captain). Jameson was the author of many novels and other books. (15)

We build a conceptual model of the text by doing a close reading, drawing inferences from what we read, and relating the parts to the whole:

- The author’s current train journey is bringing up memories of a much earlier train journey and the author’s mind is traveling through time – “one departure slid from another” – as her body travels through space.

- This journey through time is deeply disturbing (“adders” are snakes).

- The narrator’s journey through time appears to be involuntary.

- Being a passenger on a train is – like the narrator’s memory – to be unable to control the trip.

- The inability to control things might be frightening for the narrator.

- The narrator’s memory journey arrives “at last” to her first journey by train.

- The author (an adult) sees herself when she was a child – “sitting in a corner of a third-class carriage, waiting, silent, tense with anxiety.”

- The child is afraid because her mother abandoned her in a strange place.

- The stationmaster who comments to the mother – “Your little girl was afraid you weren’t coming” – seems more concerned with the child’s wellbeing than the child’s mother is.

- The mother is more concerned about her image as a responsible mother – “Nonsense. My child is never afraid.” – than she is about her child.

- The mother’s comment is also a message to the child that showing fear is not acceptable.

- If the child shows fear it might bring judgment upon the mother, which is also not acceptable.

- The mother has a Stoic attitude – British people call it “Keeping a stiff upper lip”: a commitment to avoid showing fear.

- This attitude has been dominant in England for hundreds of years (a bit of contextual knowledge about this English attitude is needed here).

- This Stoic attitude prevents people from being known by others, leading to them feeling “isolated.”

- The lessons learned by the child in this moment have affected her negatively until the present day (“I felt myself isolated by a barrier of ice from every living human being, including the husband facing me.”)

- The story identifies the harm caused by the mother, her “lesson,” and the Stoic attitude in general.

- There isn’t a clear resolution in this story, meaning that the narrator does not solve her problem of feeling isolated. Rather, she solves a different problem, which is figuring out when and where this feeling originated.

- The coda, or aftermath of the events depicted, is her writing of the story.

The “meaning” of the story is that trauma can originate in socio-cultural conditions, in this case the Stoic attitudes of Britain as exemplified by the narrator’s mother.

Notice how this step-by-step reading does the following:

- It uses evidence – in the form of quotes – from the literary text.

- It creates a conceptual “model text” – in this case it explains that the author travels backward in her mind through time and sees herself as a child who learns a painful lesson.

- It infers general statements – in this case about dominant attitudes – from specific observations of people, places, and events.

- It makes explicit that which is implied in the text.

- It argues that the literary text has a particular purpose or point – in this case to criticize the Stoic attitude in Britain.

The interpretive steps above are by no means the final word on this story and you should feel free to make your own interpretation of it. Note, however, that interpreters of literature make use of others’ work. If your interpretation goes further or in a different direction from the one above, you would make use of this example to explain how and why yours differs.

Discourses

Discourses

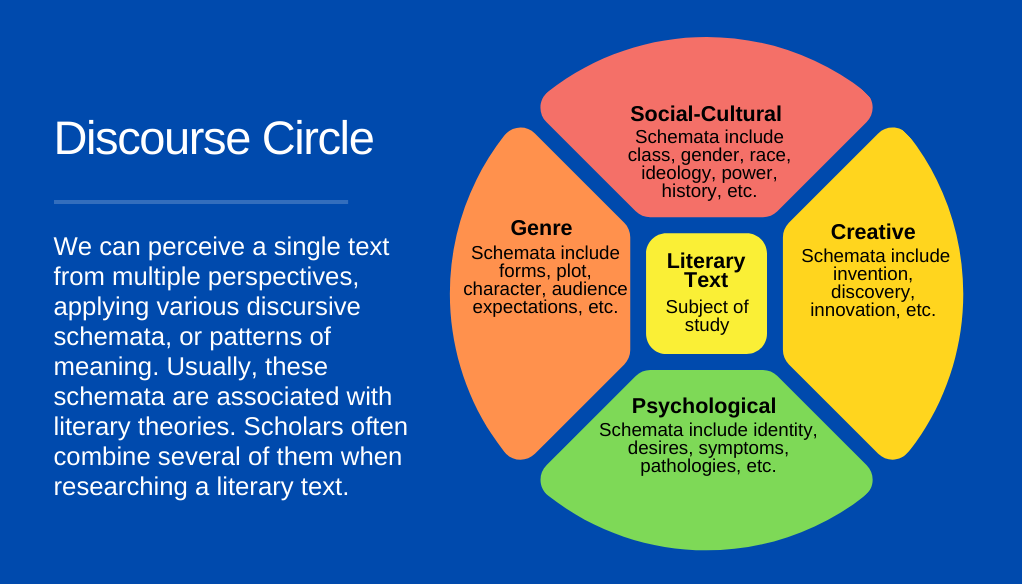

Scholars read literary works within a variety of discourses. Roughly, these discourses are grouped in four general types: social-cultural, creative, psychological, and genre:

Scholars apply discourses not only to literary texts but also to the contexts around those texts. Contexts can include the life of the author, the place and time of the writing, the audience, other literary works, critical reception of the work, etc. So, for example, a scholar may discuss the poetry of Ezra Pound using the discourse of genre, which the critic can apply both to Pound’s poetry and to his context, which includes the poetry of other writers of his time.

How to Interpret Literary Texts Using Schemata

How to Interpret Literary Texts Using Schemata

There are numerous schools of interpretation, each with their own interpretive schema. A schema is a broad theoretical framework – a meta-story – for understanding the world. We discussed a variety of these theoretical frameworks in the previous chapter. To oversimplify: psychoanalysis uses the schema of personal development; Marxism uses the schema of class struggle; feminism uses the schema of gender inequality; Christianity uses the schema of sin and redemption; etc.

Producing an Interpretation

- Notice significant details in the literary text

- Find a pattern in those details

- Map the pattern found in the literary text to an interpretive schema

- Claim that X in the literary text is really Y from the schema

When we write about a literary text, we are first creating a conceptual model – a critical description – of the text, seeing it as an author’s attempt to address a problem (which can be aesthetic, technical, social, political, etc.). The model we construct is built from a set of details about the literary work and its context, organized into a pattern. Michael Baxandall, an art critic and historian, notes that we build conceptual models any time we think or write about an object – a literary text, a person, a natural phenomenon, a concept; when we encounter any of these things we are constructing/fabricating a model of it in our minds.

Baxandall describes this conceptualizing process as it relates to creating critical descriptions of paintings.[4]

If we wish to explain pictures, in the sense of expounding them in terms of their historical causes, what we actually explain seems likely to be not the unmediated picture but the picture as considered under a partially interpretative description. This description is an untidy and lively affair.

Firstly, the nature of language or serial conceptualization means that the description is less a representation of the picture, or even a representation of seeing the picture, than a representation of thinking about having seen the picture. To put it in another way, we address a relationship between picture and concepts.

Secondly, many of the more powerful terms in the description will be a little indirect, in that they refer first not to the physical picture itself but to the effect the picture has on us, or to other things that would have a comparable effect on us, or to inferred causes of an object that would have such an effect on us as the picture does. The last of these is particularly to the point. On the one hand, that such a process penetrates our language so deeply does suggest that causal explanation cannot be avoided and so bears thinking about. On the other, one may want to be alert to the fact that the description which, seen schematically, will be part of the object of explanation already embodies preemptively explanatory elements – such as the concept of ‘design’.

Thirdly, the description has only the most general independent meaning and depends for such precision as it has on the presence of the picture. It works demonstratively – we are pointing to interest – and ostensively, taking its meaning from reciprocal reference, a sharpening to-and-fro, between itself and the particular.

These are general facts of language that become prominent in art criticism, a heroically exposed use of language, and they have (it seems to me) radical implications for how one can explain pictures – or, rather, for what it is we are doing when we follow our instinct to attempt to explain pictures. (10-11)

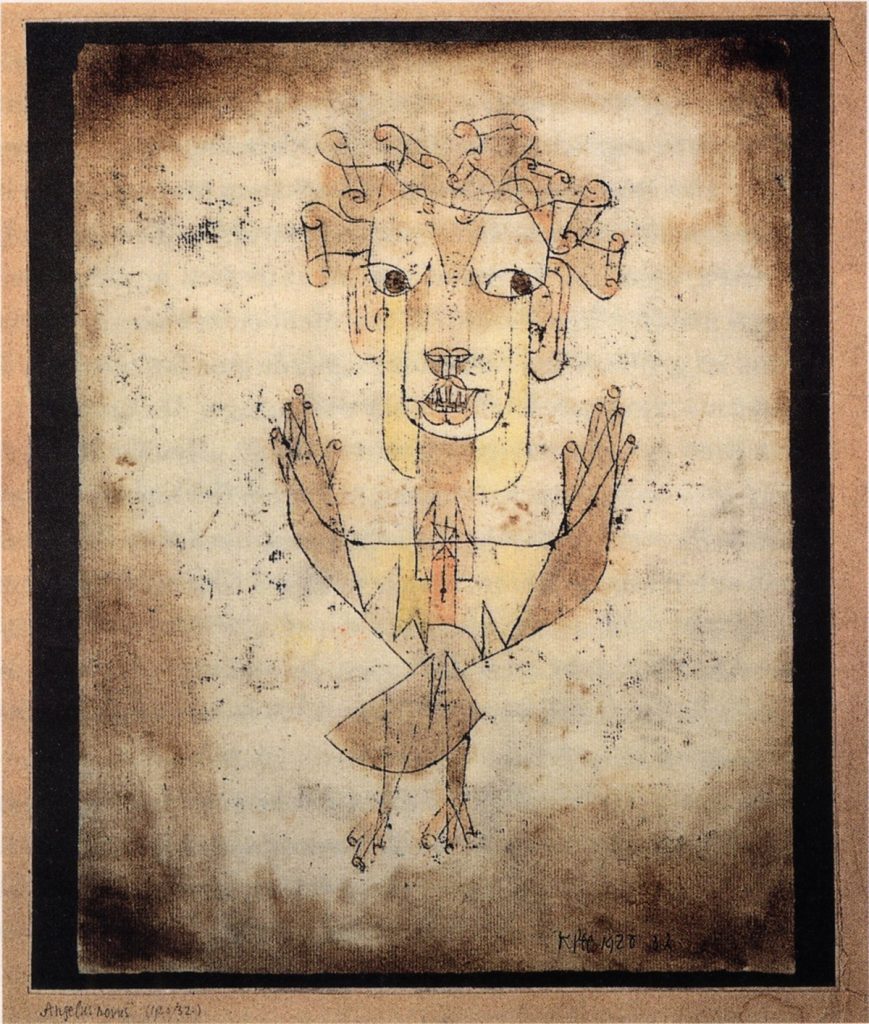

Below is an example of this kind of work by a famous critic, Walter Benjamin, writing about a picture by Paul Klee called Angelus Novus (1920):

From Benjamin:

A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

Notice that Benjamin creates a conceptual model of the picture by accounting for the details of the picture, but also by explaining what he makes up about the picture and its effect on himself. Benjamin’s reading involves his imagination and he famously turned the picture into an allegory of modernity.

From Baxandall, we can learn the process of creating conceptual models of literary works by replacing the word “picture” with “text.” In the example above in which we read Storm Jameson’s “Departures,” we built a conceptual model of the text by, in Baxandall’s terms, creating “a representation of thinking about having [read the text].” We referred “to the effect the [text] has on us, or to other things that would have a comparable effect on us, or to inferred causes of an object that would have such an effect on us as the [text] does.” Finally, “the description has only the most general independent meaning and depends for such precision as it has on the presence of the [text].”

The process of creating conceptual models often goes unrecognized. For instance, when we identify a person by their face, we are going through an enormous number of sensory and mental processes very quickly. Our brains take a bunch of shapes, lines, and colors, and construct a mental model, then compare it to an existing mental model and conclude, “Oh yeah, that’s Jane.” In working with literary texts we are more explicit about the process. For instance, in Cleanth Brooks’ writing about “Canonization,” he selects and organizes features of the text showing how they relate to one another and to his framing concept: paradox. Propp does the same thing around narrative actants and functions in folk tales.

Notice that interpretation moves from the specific to the general, from the details of the literary work into more abstract conceptual terms. Most critics only use some, not all, of the details from a literary work in the interpretation. If you disagree with a critic, you can pose a contrary interpretation by claiming that the critic overlooked significant details from the literary work, formed a misleading pattern, and mapped those details to the wrong schema. Finally, you should offer your own interpretation, following the steps outlined above. Many critics combine interpretive schemas. Also, it is acceptable to be suspicious of schema and of overarching narratives, especially ones that supposedly “explain everything.”

In the sample interpretation above, the schemata used to interpret the Storm Jameson story “Departures” is social-cultural. The interpretation views the story through a lens of cultural critique that sees Jameson as criticizing the dominant Stoic attitude in British life.

David Bordwell, in his book Making Meaning (which is primarily about film interpretation but works quite well for understanding literary interpretation), discusses two major interpretive traditions: explicatory and symptomatic. A symptomatic reading is one in which the critic treats the text with suspicion, as though it disguises its true intentions. Your goal, using this method, is to get the text to “confess” its meaning by pointing to “symptoms” in the text. Freud stated, “A symptom is a sign of, and a substitute for, an instinctual satisfaction which has remained in abeyance; it is a consequence of the process of repression” (“Inhibitions, Symptoms, and Anxiety” 20.91). The symptomatic critic is looking for signs that betray the real intention of the text or the author, just as Freud seized on forgotten names or slips of the tongue as symptoms that more accurately revealed the patient’s state of mind than did their explicit statements. In a symptomatic reading, a reader might argue that a text that seems anti-racist hides a racist intent or effect.

An explicatory reading is one in which the critic turns implied meaning into explicit meaning. An explicatory reading does not treat the literary text with suspicion. For instance, you might find a text that seems anti-racist, and your interpretation explains how it is, in fact, anti-racist.

Bordwell argues that critics often switch the way they read depending on the literary work. Some literary works ― ones that critics believe are ideologically abusive ― are read symptomatically, while other works ― those critics believe are ideologically healthy ― are read using explicatory methods.

Bordwell presents the following passage about explicatory criticism:

On a summer day, a suburban father looks out at the family lawn and says to his teen-aged son: “The grass is so tall I can hardly see the cat walking through it.” The son construes this to mean: “Mow the lawn.” This is an implicit meaning. In a similar way, the interpreter of a film may take referential or explicit meaning as only the point of departure for inferences about implicit meanings. That is, she or he explicates the film, just as the son might turn to his pal and explain, “That means Dad wants me to mow the lawn.” Explicatory criticism rests upon the belief that the principal goal of critical activity is to ascribe implicit meanings to films (Making 43).

The flip side of this paradigm is that critics tend to perform symptomatic criticism on texts they consider ideologically suspect. Bordwell explains symptomatic criticism in this passage:

On a summer day, a father looks out at the family lawn and says to his teen-aged son: “The grass is so tall I can hardly see the cat walking through it.” The son slopes off to mow the lawn, but the interchange has been witnessed by a team of live-in social scientists, and they interpret the father’s remarks in various ways. One sees it as typical of an American household’s rituals of power and negotiation. Another observer construes the remark as revealing a characteristic bourgeois concern for appearances and a pride in private property. Yet another, perhaps having had some training in the humanities, insists that the father envies the son’s sexual proficiency and that the feline image constitutes a fantasy that unwittingly symbolizes (a) the father’s identification with a predator; (b) his desire for liberation from his stifling life; his fears of castration (the cat in question has been neutered): or (d) all of the above. […] Now if these observers were to propose their interpretations to the father, he might deny them with great vehemence, but this would not persuade the social scientists to repudiate their conclusions. They would reply that the meanings they ascribed to the remark were involuntary, concealed by a referential meaning (a report on the height of the grass) and an implicit meaning (the order to mow the lawn). The social scientists have constructed a set of symptomatic meanings, and these cannot be demolished by the father’s protest. Whether the sources of meaning are intrapsychic or broadly cultural, they lie outside the conscious control of the individual who produces the utterance. We are now practicing a “hermeneutics of suspicion,” a scholarly debunking, a strategy that sees apparently innocent interactions as masking unflattering impulses (Making 71–72).

Critics employing the symptomatic approach look for “incompatibility between the film’s explicit moral and what emerges as a cultural symptom” (75). In other words, the symptomatic approach looks for instances that indicate a text’s explicit message hides a less flattering message. Such symptomatic readings warn people not to be fooled by appearances; the true, yet disguised, intentions of a text ― its “repressed meanings” ― are apparent if you know how to look for them. Explicatory criticism, by contrast, urges the audience not to miss the text’s implied messages.

The distinction between explicatory and symptomatic criticism is hinted at by their names. Both have to do with intentionality. An explicatory interpretation explains – it clarifies the author’s overt intention (and is generally flattering), while a symptomatic interpretation points to a covert intention (and is generally unflattering); it claims that a literary work is a symptom of an unflattering impulse or state of affairs.

If we look at “Tell Me a Story” by Paul Auster (below), we might say that his overt intention is to explain how he became a writer by listening to his father’s stories. His covert intention could be to reproduce his father’s evasiveness by telling stories that distract from his vulnerabilities. We might go further and argue that storytelling is a form of manipulation and control used to fool people.

Note that both kinds of criticism still use conceptual frameworks.

Steps to Interpretation

Steps to Interpretation

An interpretation, which translates the details of a literary work into the schemata of a discourse, requires that we go through a series of steps.

- A denotative reading of a text provides an inventory of what is in it. It tells us things like setting, characters, action, point of view, etc.

- A connotative reading of a text tells us what these things suggest or “mean” within their cultural context; it tells us what is implicit.

- An explicatory reading argues that a text has an overt intention; it has a purpose and lesson(s) for the reader.

- A symptomatic reading reveals that a text has a covert intention; it tries to conceal or disguise an unflattering truth.

At the very least, any interpretation must produce an explicatory reading, which is itself based upon solid denotative and connotative readings. A symptomatic reading must be based on denotative, connotative, and explicatory readings, and must show how the symptomatic reading differs from the explicatory one.

Here is a video explaining the four levels of meaning.

Example: Interpretation of excerpt from “Sonny’s Blues”

- Denotative: The narrator’s mother tells him a family secret about an uncle who was killed by white men while his brother – the narrator’s father – watched.

- Connotative: The mother wants her son – the narrator – to realize that, as was the case with the uncle, his brother Sonny is at risk even though Sonny is “good” and “smart.”

- Explicatory: The narrator retells the story to his reader because he wants us to avoid making the same mistake that he did, which is that he “pretty well forgot my promise to Mama” and failed to let his brother know he was there for him. In other words, he forgot solidarity is required to resist racism. Read within a socio-cultural framework, the mother’s story reveals the sense of entitlement and impunity that defines whiteness – “They was having fun, they just wanted to scare him, the way they do sometimes, you know” – and the precarity that defines blackness in America – “’I ain’t telling you all this,’ she said, ‘to make you scared or bitter or to make you hate nobody. I’m telling you this because you got a brother. And the world ain’t changed.’” The mother’s story to the narrator is a version of “the talk” that black parents give to their children about the dangers of living in a racist society.

- Symptomatic: Typically, a literary work that reveals a social pathology (in this case, racism), doesn’t need to be subjected to a symptomatic reading because critics understand the work as already doing a symptomatic reading (of the society). We might argue, however, that the narrator is retelling this story because he feels the need to confess his guilt for failing to fulfill his promise to his mother. But the narrator admits that motive, so stating it more plainly in our interpretation is explicatory and not symptomatic.

Reading Literary Works [Refresher]

Reading Literary Works [Refresher]

If you are using an offline version of this text, access the quiz for this section via the QR code.

Exercises

Exercises

- Practice your reading skills on the story below using explication, analysis, or comparison/contrast.

-

Make sure you tell us what the story is about. At a literal or denotative level it is about a son remembering his father telling him stories. But we also need to know at a connotative level what the story is about. Is it about the power of stories? Is it about emotional connection/disconnection? Is it about how the author became an author? Ask yourself questions like these and answer them.

-

Make sure you identify a schemata you are using – genre, social-cultural, creative, and/or psychological.

-

Make sure you create a model text from the story. I provide an example of this with the Storm Jameson text on our Interpreting Literature page.

-

Make sure you move from specific to general, showing how you made the connections. For instance, the son’s request for a story (specific) means he wants emotional connection with his father (general). The father tells a story about himself that is not true (specific), therefore deflecting his son’s request (general) but also satisfying the son’s request through substitution (general) by telling a compelling story rather than a true one (specific).

-

Tell Me a Story

I remember a day very like today. A drizzling Sunday, lethargy and quiet in the house: the world at half-speed. My father was taking a nap, or had just awoken from one, and somehow I was on the bed with him, the two of us alone in the room. Tell me a story. It must have begun like that. And because he was not doing anything, because he was still drowsing in the languor of the afternoon, he did just what I asked, launching into a story without missing a beat. I remember it all so clearly. It seems as if I have just walked out of that room, with its gray light and tangle of quilts on the bed, as if, simply by closing my eyes, I could walk back into it any time I want.

He told me of his prospecting days in South America. It was a tale of high adventure, fraught with mortal dangers, hair-raising escapes, and improbable twists of fortune: hacking his way through the jungle with a machete, fighting off bandits with his bare hands, shooting his donkey when it broke its leg. His language was flowery and convoluted, probably an echo of the books he himself had read as a boy. But it was precisely this literary style that enchanted me. Not only was he telling me new things about himself, unveiling to me the world of his distant past, but he was telling it with new and strange words. This language was just as important as the story itself. It belonged to it, and in some sense was indistinguishable from it. Its very strangeness was proof of authenticity.

It did not occur to me to think this might have been a made-up story. For years afterward I went on believing it. Even when I had passed the point when I should have known better, I still felt there might have been some truth to it. It gave me something to hold on to about my father, and I was reluctant to let go. At last I had an explanation for his mysterious evasions, his indifference to me. He was a romantic figure, a man with a dark and exciting past, and his present life was only a kind of stopping place, a way of biding his time until he took off on his next adventure. He was working out his plan, figuring out how to retrieve the gold that lay buried deep in the heart of the Andes.

–Paul Auster[5]

- Do an interpretation of the story above, using either an explicatory or symptomatic approach (see rubric below). Remember to first construct a conceptual model of the literary work, which accounts for its features.

- If there are any elements of your assignment that need clarification, please list them.

- What was the most important lesson you learned from this page? What point was confusing or difficult to understand?

Interpretation Rubric

Use of Schemata

Successfully used one or more patterns of meaning (genre, social-cultural, creative, and/or psychological) to interpret and/or critique a literary work.

Moves from Specific to General

Interpretation successfully moves from the specific to the general, from the details of the literary work into more conceptual terms.

Grammar/Mechanics

MLA or APA was used correctly while interpreting literary works. Sentence structure as well as grammar, punctuation, and capitalization were used correctly with minimal to no errors.

- In the “Back Matter” of this book, you will find a page titled “Rubrics.” On that page, we provide a rubric for Interpreting Literary Works Rubric. ↵

- Storm Jameson, "Departures." From Journey from the North: Autobiography of Storm Jameson ↵

- Scholes, Robert, et al. Text Book: Writing Through Literature. United States, Bedford/St. Martin's, 2001. ↵

- Michael Baxandall: Patterns of Intention–On the Historical Explanation of Pictures. Yale University Press, 1981. ↵

- Paul Auster, "Tell Me a Story." From The Invention of Solitude, by Paul Auster. ↵