Intercultural Competence

Barry Mauer; John Venecek; and Erika Heredia

We discuss the following topics on this page:

- Introduction

- Discussion of James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues”

- Framing

- Intercultural Competence Learning Objectives

- From Ethnocentrism to Ethnorelativism

- Cultures and Subcultures

We also provide the following:

Introduction

Introduction

Until a few decades ago, academic programs focused almost exclusively on literature by DWM (Dead White Men). Then social movements such as civil rights, feminism, LGBTQ+ equality, and anti-colonialism drew attention to writing by women, nonwhite, nonwestern, queer, and contemporary authors, leading to more variety in the literature we study. The group of researchers studying literature has become more varied too as educational opportunities grew for marginalized groups, and networked media created more global connections. Entering the scholarly conversation about literature is more complicated in some ways now; we need intercultural competence to participate in it effectively and respectfully.

Intercultural competence does not just mean knowledge of different religions, nations, ethnic groups, linguistic communities, genders, etc. It also means learning to perceive one’s own culture differently and to examine its rules, values, styles, beliefs, and practices, understanding them as historically contingent (i.e., invented by people in relation to their specific historical circumstances), rather than as unproblematically “natural” or “eternal.”

Discussion of James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues”

Discussion of James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues”

James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues” offers a complex set of challenges requiring intercultural competence. Set mostly in Harlem, New York City, in the 1940s and 1950s, the story opens with news of Sonny’s arrest on drug charges, and it closes with the narrator, who is Sonny’s brother, hearing Sonny play jazz at a nightclub in Greenwich Village (also in New York City). When the narrator hears his brother play, he understands something fundamental about Sonny, and about himself, for the first time (we will discuss what that understanding is further below).

“Sonny’s Blues” asks readers to learn about the blues, which is at the root of the jazz music that Sonny plays. Even though black musicians were central to the development of jazz music, not all black Americans liked or even understood the music. Jazz was a subculture with its own rules, values, styles, beliefs, and practices, and Baldwin illustrates how misunderstood it was even in black communities. In the following scene, the narrator, and his brother Sonny, have just been to their mother’s funeral. Before she died, the mother told the narrator to take care of his younger brother, Sonny. In this scene, the narrator tries to find out who Sonny is as a person.

Excerpt from Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues”

And, after the funeral, with just Sonny and me alone in the empty kitchen, I tried to find out something about him.

“What do you want to do?” I asked him.

“I’m going to be a musician,” he said.

For he had graduated, in the time I had been away, from dancing to the juke box to finding out who was playing what, and what they were doing with it, and he had bought himself a set of drums.

“You mean, you want to be a drummer?” I somehow had the feeling that being a drummer might be all right for other people but not for my brother Sonny.

“I don’t think,” he said, looking at me very gravely, “that I’ll ever be a good drummer. But I think I can play a piano.”

I frowned. I’d never played the role of the older brother quite so seriously before, had scarcely ever, in fact, asked Sonny a damn thing. I sensed myself in the presence of something I didn’t really know how to handle, didn’t understand. So I made my frown a little deeper as I asked: “What kind of musician do you want to be?”

He grinned. “How many kinds do you think there are?”

“Be serious,” I said.

He laughed, throwing his head back, and then looked at me. “I am serious.”

“Well, then, for Christ’s sake, stop kidding around and answer a serious question. I mean, do you want to be a concert pianist, you want to play classical music and all that, or – or what?” Long before I finished he was laughing again. “For Christ’s sake, Sonny!”

He sobered, but with difficulty. “I’m sorry. But you sound so – scared!” and he was off again.

“Well, you may think it’s funny now, baby, but it’s not going to be so funny when you have to make your living at it, let me tell you that.” I was furious because I knew he was laughing at me and I didn’t know why. “No,” he said, very sober now, and afraid, perhaps, that he’d hurt me, “I don’t want to be a classical pianist. That isn’t what interests me. I mean” – he paused, looking hard at me, as though his eyes would help me to understand, and then gestured helplessly, as though perhaps his hand would help – “I mean, I’ll have a lot of studying to do, and I’ll have to study everything, but, I mean, I want to play jazz,” he [Sonny] said.

Well, the word had never before sounded as heavy, as real, as it sounded that afternoon in Sonny’s mouth, I just looked at him and I was probably frowning a real frown by this time. I simply couldn’t see why on earth he’d want to spend his time hanging around nightclubs, clowning around on bandstands, while people pushed each other around a dance floor. It seemed – beneath him, somehow. I had never thought about it before, had never been forced to, but I suppose I had always put jazz musicians in a class with what Daddy called “good-time people.”

“Are you serious?”

“Hell, yes, I’m serious.”

He looked more helpless than ever, and annoyed, and deeply hurt. I suggested, helpfully: “You mean – like Louis Armstrong?”

His face closed as though I’d struck him. “No. I’m not talking about none of that old-time, down home crap.”

“Well, look, Sonny, I’m sorry, don’t get mad. I just don’t altogether get it, that’s all. Name somebody – you know, a jazz musician you admire.”

“Bird.”

“Who?”

“Bird! Charlie Parker! Don’t they teach you nothing in the goddamn army?”

I lit a cigarette. I was surprised and then a little amused to discover that I was trembling. “I’ve been out of touch,” I said. “You’ll have to be patient with me. Now. Who’s this Parker character?”

“He’s just one of the greatest jazz musicians alive,” said Sonny, sullenly, his hands in his pockets, his back to me. “Maybe the greatest,” he added, bitterly, “that’s probably why you never heard of him.”

“All right,” I said, “I’m ignorant, I’m sorry. I’ll go out and buy all the cat’s records right away, all right?”

“It don’t,” said Sonny, with dignity, “make any difference to me. I don’t care what you listen to. Don’t do me no favors.”

Example [Discussion of James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues”]

Example [Discussion of James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues”]

Listen to a bit of Bird’s playing from “Night in Tunisia.”

Charlie Parker on Night in Tunisia take 1 march ’46 [0 min 34 sec]

Framing

Framing

The way we approach other cultures is through a device called “framing”; a particular word or phrase evokes a frame that characterizes a subject in such a way that it leads automatically to a judgment. The narrator here recalls his father’s framing of jazz musicians as “good-time people.” This framing sets up an opposition between people who work (use their time productively) and people who play (waste their time profitlessly). Thus, using the term “good-time people” to characterize jazz musicians could make us judge them as useless or even dangerous. But being a good musician in any style of music takes serious effort and jazz music can have many purposes beyond just “good times.” It can bring communities together, pay homage, and showcase creativity. The narrator here lacks the intercultural competence necessary to understand his own brother!

Intercultural competence requires knowledge, skills, and attitudes. The list below summarizes The American Association of Colleges and Universities’ (AACU’s) rubric on Cultural Competence.

Intercultural Competence Learning Objectives

Intercultural Competence Learning Objectives

- The knowledge of one’s own culture, its rules and biases, and how history has shaped these rules and biases.

- The knowledge of cultural frameworks (the way members of other cultures view “their history, values, politics, communication styles, economy, or beliefs and practices”).

- The skill of empathy (the ability to “interpret intercultural experience from the perspectives of [one’s] own and more than one worldview”).

- The skill of understanding differences in verbal and nonverbal communication between cultures.

- The attitude of curiosity (“asks complex questions about other cultures, seeks out and articulates answers to these questions that reflect multiple cultural perspectives”).

- The attitude of openness (“Initiates and develops interactions with culturally different others”).

From Ethnocentrism to Ethnorelativism

From Ethnocentrism to Ethnorelativism

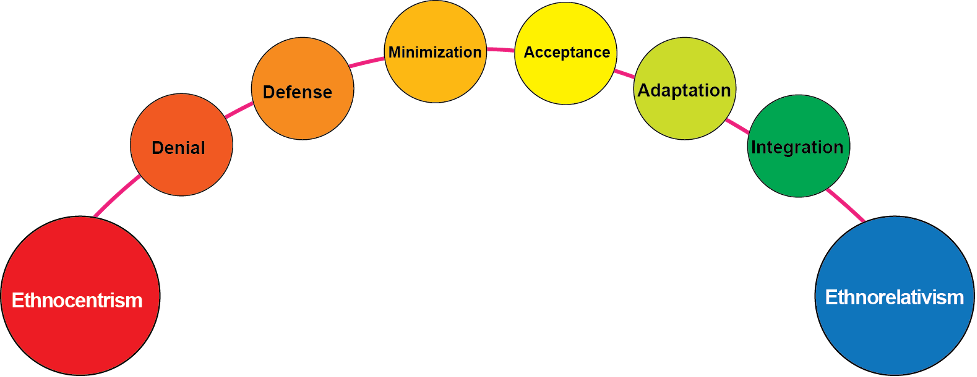

“Sonny’s Blues” is, in part, about the narrator’s transformation from ethnocentrism (in which different perspectives are denied, or ignored, and one’s own culture is the only thing taken into account) to ethnorelativism (where one’s own culture is considered as one perspective among many more that propose alternative worldviews).

Denial

When people are in cultural denial, they perceive another culture in a simplistic way, without recognizing particularities and often through stereotypes. For example, all jazz musicians are “good-time people.” Such denial denigrates others simply because they belong to a certain group.

Defense

When people are in defense mode, they feel threatened by another culture and seek to defend their own culture. The narrator of “Sonny’s Blues,” Sonny’s brother, has a college degree and works as a teacher; he defends his culture (valuing family life and a career) by suggesting that Sonny, unlike himself, will be unable to earn money: “Well, you may think it’s funny now, baby, but it’s not going to be so funny when you have to make your living at it, let me tell you that.” The narrator seeks to curtail Sonny’s choices because Sonny’s culture is different – and seen as inferior – to the narrator’s.

Minimization

When people use minimization, they deny cultural differences and make broad claims about the similarity of all human experiences. Thus, they avoid learning about other cultures and empathizing despite the differences. The narrator in “Sonny’s Blues” tries to bridge his differences with Sonny by arguing that everyone suffers; therefore, the two brothers are not really that different.

I said, “that there’s no way not to suffer. Isn’t it better, then, just to – take it?”

“But nobody just takes it,” Sonny cried, “that’s what I’m telling you! Everybody tries not to. You’re just hung up on the way some people try – it’s not your way!

As the group Organizing Engagement points out:

By reframing cultural differences in terms of human sameness, minimization enables people to avoid recognizing their own cultural biases, avoid the effort it would take to learn about other cultures, or avoid undertaking the difficult personal adaptations required to relate to or communicate more respectfully across cultural differences. [Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity]

Acceptance

When people show acceptance, they identify cultural differences and accept that culture shapes personal beliefs, behaviors, and values in some ways. Acceptance does not mean agreement with another culture, but it does imply tolerance. The narrator of “Sonny’s Blues” shows some acceptance by recognizing that the world of the nightclub is truly different from the world he inhabits.

… it turned out that everyone at the bar knew Sonny, or almost everyone; some were musicians, working there, or nearby, or not working, some were simply hangers-on, and some were there to hear Sonny play. I was introduced to all of them and they were all very polite to me. Yet, it was clear that, for them, I was only Sonny’s brother. Here, I was in Sonny’s world. Or, rather: his kingdom. Here, it was not even a question that his veins bore royal blood.

Adaptation

When people are in the process of adaptation, they can interact in another cultural environment in a relaxed and productive way. They are not seeking to assimilate the other culture to their culture, but rather come with the purpose of learning and developing empathy. While the narrator is listening to his brother begin his performance, he starts thinking about the differences between himself (the person who hears music) and his brother (the person who makes music) in more adaptive terms.

All I know about music is that not many people ever really hear it. And even then, on the rare occasions when something opens within, and the music enters, what we mainly hear, or hear corroborated, are personal, private, vanishing evocations. But the man who creates the music is hearing something else, is dealing with the roar rising from the void and imposing order on it as it hits the air. What is evoked in him, then, is of another order, more terrible because it has no words, and triumphant, too, for that same reason. And his triumph, when he triumphs, is ours.

Integration

When people are in the process of integration, they integrate elements from other cultures into their own cultural experience. They not only accept other points of view but incorporate some of them authentically. As Bennett explains:

Integration of cultural difference is the state in which one’s experience of self is expanded to include the movement in and out of different cultural worldviews…. people are able to experience themselves as multicultural beings who are constantly choosing the most appropriate cultural context for their behavior.

The narrator, Sonny’s brother, finally reaches this point when he recognizing that Sonny’s music benefits both of them.

I seemed to hear with what burning he had made it his, with what burning we had yet to make it ours, how we could cease lamenting. Freedom lurked around us and I understood, at last, that he could help us to be free if we would listen, that he would never be free until we did. Yet, there was no battle in his face now. I heard what he had gone through, and would continue to go through until he came to rest in earth. He had made it his: that long line, of which we knew only Mama and Daddy. And he was giving it back, as everything must be given back, so that, passing through death, it can live forever. I saw my mother’s face again, and felt, for the first time, how the stones of the road she had walked on must have bruised her feet. I saw the moonlit road where my father’s brother died. And it brought something else back to me, and carried me past it, I saw my little girl again and felt Isabel’s tears again, and I felt my own tears begin to rise. And I was yet aware that this was only a moment, that the world waited outside, as hungry as a tiger, and that trouble stretched above us, longer than the sky.

Here the narrator is accepting the gift that Sonny is offering him: access to his world, the world of jazz. In this jazz world, there is meaning and value and the narrator is incorporating it in his own life and encouraging others to do the same.

Cultures and Subcultures

Cultures and Subcultures

Intercultural competence asks a lot of us. It requires, “knowledge of cultural worldview frameworks.” For instance, “Sonny’s Blues” discusses a split within the jazz world. Bebop, the music that the fictional Sonny played and that real life Charlie Parker pioneered in the early 1940s, was perceived as a distinct break from earlier forms of jazz. Unlike earlier forms, Bebop was aggressively avant-garde. Its leading practitioners did not aspire to make “popular” music as much as they sought to expand the expressive possibilities of music. For a while, there was animosity within the jazz community (mostly from some elder jazz musicians towards the younger bebop musicians). Louis Armstrong, a famous jazz innovator who had gained fame in the 1920s, said of bebop: “All them weird chords which don’t mean a thing . . . you got no melody to remember, and no beat to dance to.” Later, Armstrong befriended some of the Bebop jazz musicians, such as Dizzy Gillespie, and came to appreciate their work.

Gillespie and Armstrong

Learning about the styles of jazz, the people involved, the social and economic conditions, the historical changes, and other factors requires a good bit of research. Such research may be necessary to understand Sonny and his culture.

Key Takeaways

Key Takeaways

| Do: | Don’t: |

|---|---|

| Examine your own culture’s rules, values, styles, beliefs, and practices. | Ignore your own culture by focusing only on another culture. |

| Understand culture as historically contingent (i.e., invented by people in relation to their specific historical circumstances). | Understand culture as unproblematically “natural” or “eternal.” |

| Notice how you frame other cultures (framing characterizes a subject in such a way that it leads automatically to a judgment). | Accept the way you frame other cultures without questioning that frame. |

| Develop an ability to perceive the world through the lens of another culture (even if you disagree with it). | Refuse to see the world through another cultural lens because you disagree with it. |

| Develop a complex understanding of cultural differences in terms of verbal and nonverbal communication. | Use a simplistic understanding of cultural differences, or overlook cultural differences. |

| Ask complex questions of other cultures and seek answers that include multiple perspectives. | Ask simplistic questions of other cultures and/or seek answers that include only one perspective. |

| Be open to interactions with people of other cultures, and even initiate such contact. | Be closed-off to people from other cultures. |

If you are using an offline version of this text, access the quiz for this section via the QR code.

- Graphic by Erika Maribel Heredia illustrating Milton Bennett’s research on cultural awareness. ↵