Foundational Materials Assignment

Barry Mauer and John Venecek

“I never know what I think about something until I read what I’ve written on it.”

―

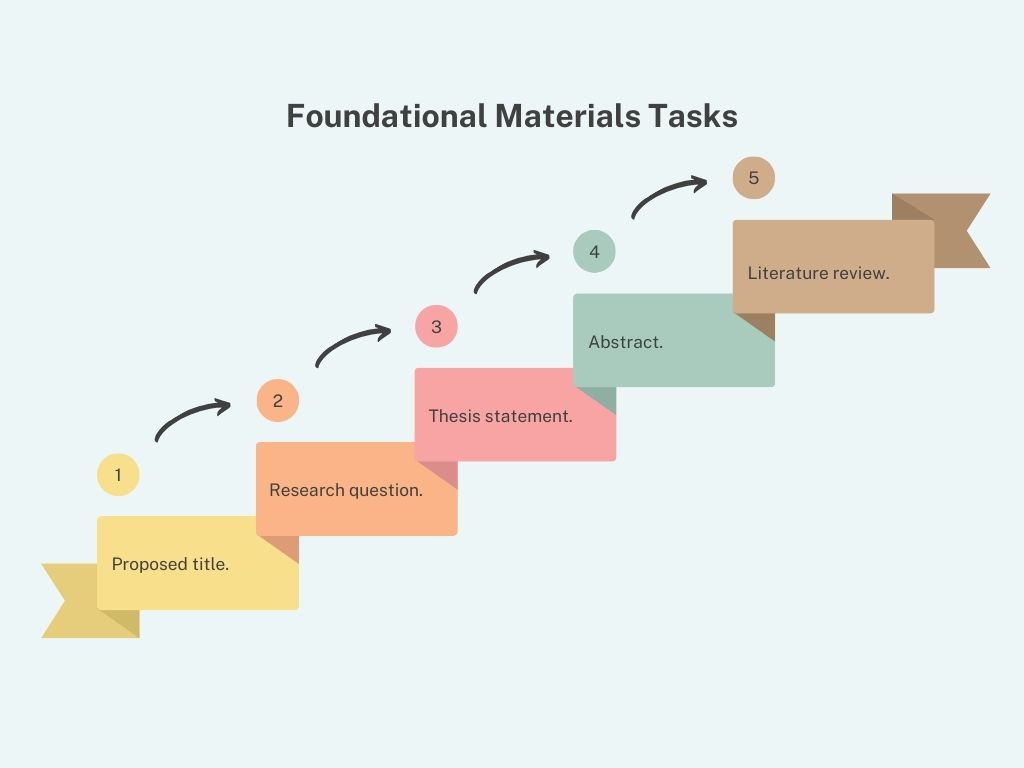

This assignment is a major step on your way to the research project. It includes the following components:

Rubrics for each of these components are available in the “Rubrics” section of the appendix. You can absolutely re-use past assignments here, but it is a good idea to rework them, especially once you see all the parts together. Think about how all the parts relate to one another and adjust them if they need to be more cohesive.

If you’ve been following this textbook, you should have completed all these steps by now. For this assignment, you put them together and see that they all relate. Your Foundational Materials work may only end up a couple of pages long, but we are going for quality not quantity. Begin with a clear sense of audience and purpose, and clearly define the problem, research question, thesis, and argument. Provide context for your work by citing the scholarly discussion. You should identify a journal or other scholarly platform (conference, showcase, edited collection, etc.) that would be a good fit for your research.

Your arguments need specificity, strength, support, and coherence. Please ask for your instructor’s feedback or help if you need it before turning in this assignment.

If your instructor has given you a choice of prompts, indicate which prompt from the project assignments you are referring to. By choosing one, you are choosing the “frame” for your work. Make sure you incorporate key terms in your proposal. If your research is about metaphor in a literary work, you need to explain which metaphor(s) in particular you are addressing. It shouldn’t be about metaphor in general. The parts of the assignment, such as composing a title, developing a research question, writing a thesis statement, and so on, are explained in the chapters of this book. Following the advice in these pages will help you stay away from many common yet avoidable mistakes.

-

- Titles: If a key word appears in your title, it needs to appear somewhere else in your proposal.

- The title should indicate which text is your object of study. It should also indicate which theory, methodology, or method you are using to discuss the work.

- Your title needs to give the reader some guidance on what to expect in the paper. Imagine that your title is listed among twenty other titles in a journal – how will readers know which text you are discussing? Which theory or perspective are you taking?

- You should capitalize all words in your title except for prepositions (unless a preposition is at the beginning of the title, in which case you capitalize it).

- Your own title does not go in quotation marks.

- It is a mistake to imply in your title that a particular writer is using a theory in their writing (as in this made-up example: “Judith Williamson’s Myth Structure in Poe’s ‘The Masque of the Red Death.’” The word “in” here implies that Williamson’s theory is in the story itself. Instead, you could say you are doing a reading of the story through Williamson’s theory).

- Research questions: An assignment prompt is not the same thing as your research question.

- Your research question should be aimed at filling a gap in the scholarly literature or clearing up a misunderstanding about a topic related to literature.

- A research question can include primary, secondary, and tertiary questions.

- What is it you want to know about this text?

- Don’t make your research question too broad.

- Make your research question about a specific text (usually no more than two for an undergraduate paper) and specific topics (such as particular metaphors or paradoxes, social or psychological questions, etc.).

- The research question should be answerable with an arguable claim.

- Make sure your research question is relevant to an audience of literary scholars.

- Don’t ask whether we can apply a theory to a text. We can apply almost any theory to almost any text, but what is it you want to know about the text? Is there some specific benefit we gain from a theory that can’t be gained by other means?

- Thesis statement: Writing a good thesis statement is one of the most difficult tasks in academic writing.

- Your thesis statement should answer your research question.

- It should relate to a specific text or texts, rather than (merely) to a general topic.

- Because you are stating an arguable claim, you should do more than claim you will discuss or will analyze a text (these terms imply an explicatory paper, which is “about” something, and not an argumentative one that makes a claim).

- Avoid claiming we can “understand” a text (instead tell us what we should understand).

- Avoid making claims that are presumptive (already known or generally accepted), such as that Ernest Gaines’ writing is about injustice. Tell us what actions he portrays that are unjust and explain why they are unjust.

- Avoid vague language. Stating that something is “different” or “unique” is not an arguable claim.

- Avoid claiming that a text is an example of a theory. Most theories are general enough to cover a potentially infinite number of examples. Tell us what is special about a text and why it matters.

- Avoid claiming that you will prove a theory. If a theory is in the scholarly literature, it is presumptively true. You can criticize a theory or even seek to disprove it. You can explain how other theorists have amended and extended particular theories. (Remember that a theory is not a fact; it is an explanation that accounts for a set of facts).

- Keep your thesis statement as short as possible (though it can be several sentences) and put longer explanations in the abstract.

- Abstract: Explain what your research contributes to the scholarly conversation. Your abstract should explain your argument in more detail and provide an idea of what support you are using and why your claim is significant.

- Literature Review: How are you positioning your argument in relation to that of other scholars? Which ones do you agree with or disagree with? Of the ones that agree, how will your work differ from or add to theirs? Are you deviating from other scholarship in some ways? Building upon it? Providing meta-commentary on it?

- Which sources are you using for evidence?

- How does your work contribute to the scholarly discussion?

- Keep in mind that your sources may focus on different things: the literary work, the theory, the methodology, etc.

- If your proposal refers to a theory or method, include something about it in the bibliography about it. Sometimes one source you found will be closest to the paper you are writing. You can use it as your primary jumping off point – how does your work differ or supplement this work?

- Each work listed in your literature review should have a full citation. Make sure your citations are properly formatted (MLA, APA, etc.).

- If you’d like to see an excellent example of a literature review, see this one about narratology by Carissa Baker.

- Titles: If a key word appears in your title, it needs to appear somewhere else in your proposal.

Stylistics: General scholarly practice is to write in present tense. In other words, avoid writing “this paper will . . . ,” which is future tense.

-

-

- Avoid passive voice sentences, especially agentless ones that don’t tell us who is doing what.

- Make sure your arguments are strong and clear and that there are no mechanical or style problems to slow down your reader. Your reader wants to learn and enjoy – they do not want to struggle to figure out what you mean, how your ideas are connected, or to confront style problems. Writers work harder so that their readers don’t have to.

- Short story titles go in quotation marks and book titles go in italics.

- Avoid using “this” as a stand-alone pronoun, which leads to vagueness.

-

If your project uses a theory outside of its normal application, then explain why it is doing so and how you are making it work. For instance, Vladimir Propp’s morphological theory is about folktales. If you are applying Propp’s theory to a modernist literary work, explain why Propp’s theory is relevant outside of folktales. Your reader may think, for example, that modernist works don’t follow the narrative structures of folktales and that applying Propp to one will just tell us what we already believe – that folktales and modernist literary works are different. But if applying Propp to a modernist literary work reveals something about that work we could not have understood otherwise, then by all means, use it!

Research projects take time to prepare and write. Be sure to schedule time regularly to do this work. Start with something very manageable like 15 minutes a day, and then if you go over that time, consider it a bonus. The hardest part is starting.

Plagiarism is a serious academic offense that can lead to expulsion from the university. You must properly cite your sources, using quotation marks (or offsetting longer quotes) and providing proper citation. See Avoiding Plagiarism for information.