Finding Trustworthy Sources

Barry Mauer and John Venecek

We discuss the following topics on this page:

We also provide the following activity:

This page addresses several questions: How do we know which sources to trust? What sources will our audience find most relevant and significant? How important is currency (not money, but information that is the most recent)? Should we be concerned about whether a source is “biased”? How do we avoid repeating misinformation to our audience? At the heart of these questions is the issue of “authority,” which is the trust we grant to reliable sources of information.

Authority is Constructed and Contextual[1]

Authority is Constructed and Contextual[1]

Information resources reflect their creators’ expertise and credibility and are evaluated based on the information needed and the context in which the information will be used. Authority is constructed in that various communities may recognize different types of authority. It is contextual in that the information needed may help to determine the level of authority required.[2]

Is there ever a good reason to use low quality sources in a research paper? If our goal is to show readers the difference between good and bad information, then reproducing the unreliable information is justified (because we are identifying it as such). Researchers can and should discuss the false and dangerous things people believe, or what they want others to believe, without falling into the trap of believing it themselves. Therefore, purposely looking for low sources of information might be justified. Problems occur, however, when researchers confuse low quality information with high quality information. We need to maintain a set of standards and use our critical judgment when evaluating sources to ensure that statements of fact are indeed true and that claims follow allowable inferences. It is our responsibility to make proper assessments of information sources and to point out flaws when we find them.

The usefulness of a resource will differ by discipline and the scope of your project. For example, currency, meaning the work was published more recently, is extremely important in the sciences but not always so in the humanities where scholars routinely work with classic texts. In the digital humanities, and in any field that deals with digital media, things will develop faster and, therefore, currency will be more relevant.

As you conduct your literature review, you should be aware of criteria such as currency, relevance, authority, and purpose, but do so with what the Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL) calls an “attitude of informed skepticism and an openness to new perspectives, additional voices, and changes in schools of thought.” Effective researchers “understand the need to determine the validity of the information created by different authorities and to acknowledge biases that privilege some sources of authority over others, especially in terms of others’ worldviews, gender, sexual orientation, and cultural orientations.”

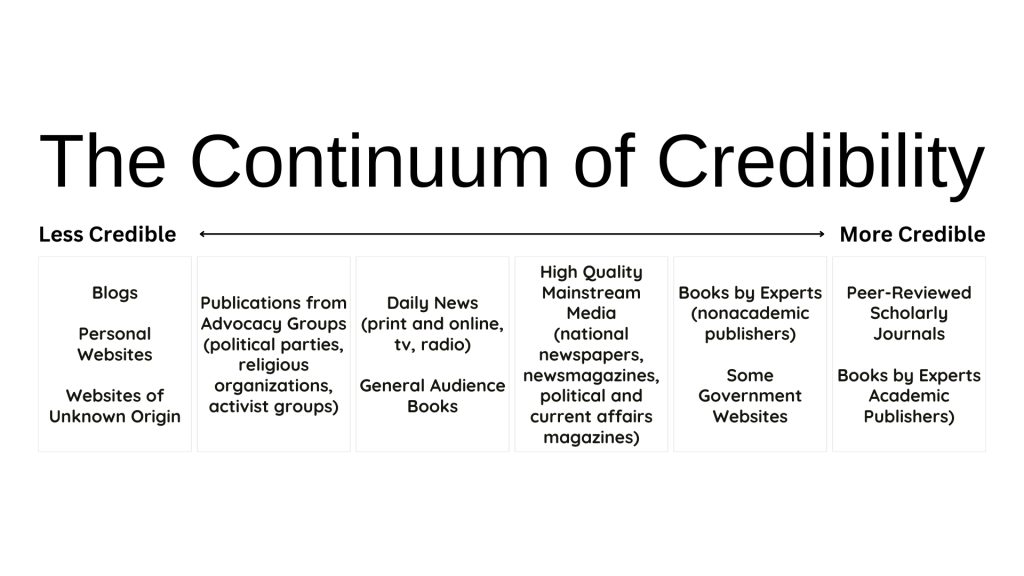

Many novice scholars make the mistake of doing a quick web search without going any further. The materials a scholar finds through this method can be extremely poor. The method most likely to produce credible materials is to search academic library databases for peer-reviewed scholarly sources (see the “Continuum of Credibility” below). Even within the scholarly sources, there are more and less credible sources.

The continuum above is just a guide and not a law. A blog – which is categorized as “less credible” here – may contain credible information; a blog may cite information from a peer-reviewed scholarly journal, for instance, or the author of the blog is a scholar with expertise in the area under consideration. We need to exercise independent judgment when assessing the credibility of sources. For a more complete overview of constructing authority, see the ACRL Framework . In the meantime, open the chart below to see some criteria for evaluating the credibility of scholarly resources. Most of these focus on journals but can be applied to any type of academic resource.

Aristotle’s Ethos

Aristotle’s Ethos

Aristotle’s term ethos evaluates expertise in these terms. Ethos has an ethical dimension and is separate from self-confidence or popularity since it is possible to be self-confident and popular without any ethical grounding. We can get a sense of whether an authority is ethical by investigating how others have evaluated their work. Over time, scholars get a reputation from other scholars who evaluate their knowledge, trustworthiness, and disinterestedness.

Aristotle was suspicious of people who argued for money. Cynically promoting views you don’t agree with in order to profit personally constitutes a form of malpractice. Honest self-advocacy is fine, however. For instance, disabled scholars who advocate for better transportation for people with disabilities do not present ethical problems with their advocacy.

A Note about Bias

A Note about Bias

We routinely hear that “bias” is bad; therefore, the reasoning goes, if we find a work of scholarship that shows “bias,” we should reject it. But not all bias is bad. If bias is towards the truth, then we should accept it. If we hear two scholars arguing about what the moon is made from, and one says cheese and the other says rock, we should not discount the one who says rock because it appears they are biased. As scholars, we are called upon to act as referees, and it is up to us to take sides when necessary. In this example, claiming that both sides are right – or that the truth is in the middle – is a dereliction of our duty as scholars. It is warranted to be biased against the bad behavior or false claims of scholars, but it is not warranted to be biased against good evidence and arguments, nor is it warranted to be biased against scholars based on their race, gender, or other identity categories. If we notice unwarranted bias in the work of other scholars, we have an obligation to point it out in our work.

If you are using an offline version of this text, access the quiz for this section via the QR code.

- In the “Back Matter” of this book, you will find a page titled “Rubrics.” On that page, we provide a rubric for Finding Trustworthy Sources ↵

- Association of College and Research Libraries. "Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education." 2016. https://www.ala.org/acrl/standards/ilframework ↵

- Adapted from "Public Administration Research: Evaluate Sources." UCCS. https://libguides.uccs.edu/c.php?g=617840&p=4299162 ↵

The character of a speaker or rhetor.

They are not invested in a particular outcome and stand to gain or lose nothing by taking a side in a dispute.