Critiquing Literary Works

Barry Mauer and John Venecek

We discuss the following topics on this page:

- Introduction

- Critical Discourses

- Case Study: Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro”

- The Stakes of Criticism

- Steps to Criticism

- Sample Criticism

- Takeaways

We also provide the following activities:

Introduction

Introduction

Critique is something we do all the time when we consume media like books, television shows, movies, or online content. Critique just means we explain why something is good or bad, or why we like it or dislike it. It covers praise and blame and everything in between. The key to critique is to supply reasons for our judgment. The better the reasons, and the more we connect them to the text or to our experience of the text, the better the critique.

Critics aim to improve literature and many critics believe literature, in certain circumstances, can improve society. Literature is certainly about pleasure and displeasure, but it is also about what is true and false, and what is right and wrong. The “stakes” of criticism, therefore, are usually much higher than promoting or demoting a particular literary work. The larger aim of critique is to set a high bar for what counts as quality literature; the word “quality” can refer to form or structure, features, originality, purpose, function, effects, or any other aspect of a literary work.

Literary scholars often engage in critique, meaning they evaluate the quality of a literary work. Critique is not just a matter of personal opinion, though scholars can and do have personal preferences, because critique requires research into evaluative criteria and the particulars of each literary work. In addition, critique is comparative; it claims that a literary work is superior, inferior, or equal to another literary work. Critique is not just descriptive (i.e., detailing the features of a literary work); it is also prescriptive (i.e., it tells us what good literary writing should be). Students sometimes imagine that “critique” means finding things wrong with a piece of literature. It doesn’t have to be that at all. You can praise a work too. You just have to explain why it’s praise or blameworthy.

Literature can be critiqued using a vast number of criteria. For instance, a poem can be critiqued for its choice of subject and theme, setting, speaker, addressee, imagery, word choice, rhythm, sounds, repetition, form, structure, tone, pace, title, flow, use of irony, metaphor, allusion, and hundreds of other factors. Each poem can be compared to others in terms of originality, significance, artfulness, insightfulness, and power. To be an effective critic, you have to keep asking yourself and the text questions. The more questions you produce, the better. Another point is that you can evaluate not just the literary work but also your experience of the work. You can discuss whether you find pleasure in reading the work (a lack of pleasure doesn’t necessarily mean you had a bad experience or that the work is bad), difficulty, or emotions like apprehension, suspense, or satisfaction.

Many students are reticent to critique literary works, believing that art, like literature, should not be judged, or that all art is more or less equal, or that it is unfair to judge a work of art or an artist because it might hurt someone’s feelings or sensibilities. But these excuses for avoiding critique don’t really stand up for the simple reason that literary authors are themselves critical of their work. They read other authors’ works and determine for themselves what counts as good and what doesn’t. Most authors want to produce something “good” or “better,” whatever those terms mean to them. So if authors use critique to evaluate literature, surely critics can too.

Critical Discourses

Critical Discourses

Critics use a variety of critical discourses to evaluate literary works. These discourses contain values and sets of criteria that help us determine literary quality. Some critical discourses focus on social and political issues in and around the writing, while others focus on formal qualities of the writing itself: its structure, language, and themes. Many critics accept that literary form has political implications and that the two types of criticism – social and formal – can’t be easily separated.

Literary criticism can address three general areas: the true, the good, and the beautiful. Emanuel Kant referred to these as the “three critiques”: the critique of pure reason (about the true and the false), critique of practical reason (about right and wrong), and the critique of judgment (about the beautiful and the sublime).

How do we judge a literary work in terms of truth given that it may be fictional and/or subjective? For instance, how do we judge Arkady and Boris Strugatsky’s science-fiction novel Roadside Picnic, about the aftermath of an alien visit to Earth, when there is no factual basis for the novel’s premise? We would judge such a work not on its factual accuracy but on its epistemic value. The novel may tell us true things about human behavior (based in greed, fear, curiosity, reverence, loyalty, guilt, etc.) and how the world works in general (with its rules, boundaries, mysteries, and consequences), and not about any particular aliens. It is up to the literary critic to assess the value of the novel’s claims about human behavior and how the world works in general.

How do we judge a literary work in terms of right and wrong? Kate Chopin’s short story, “The Kiss,” is a classic subject of discussion in these terms. In the story, a young woman named Nathalie is aiming to marry a wealthy but unimpressive man named Brantain while continuing a sexual relationship with a handsome but less wealthy man, Harvy. The striking thing about the story is the narrator’s lack of judgment about Nathalie’s behavior. Why doesn’t the narrator condemn Nathalie for her indiscretion and manipulation of the other characters? Because the narration doesn’t judge Nathalie’s behavior on moral terms, the burden of judgment shifts to the reader. We might be tempted to immediately condemn Nathalie, but we might hesitate because Chopin is showing us a bigger picture: Nathalie has no means of attaining wealth except through marriage, and Brantain and Harvy are also playing games; Brantain is using his money to buy an attractive wife while Harvy is using his privilege as a male to have sexual satisfaction without consequences. They are all manipulating other people. We might save our condemnation of the individual players and focus it instead on the unfair gender and class system that underlies these games.

How do we judge a literary work in terms of the beautiful and the sublime given that taste can be far more subjective than questions of true and false or right and wrong? Wikipedia summarizes Kant’s ideas about taste:

The remaining two judgments — the beautiful and the sublime — differ from both the agreeable and the good. They are what Kant refers to as “subjective universal” judgments. This apparently oxymoronic term means that, in practice, the judgments are subjective, and are not tied to any absolute and determinate concept. However, the judgment that something is beautiful or sublime is made with the belief that other people ought to agree with this judgment — even though it is known that many will not. The force of this “ought” comes from a reference to a sensus communis — a community of taste.

The literary critic, instead of claiming that a literary work is beautiful or sublime, may claim instead that a literary work ought to be recognized collectively as beautiful or sublime. The sublime is a category beyond the beautiful and can include things that inspire awe or fear. A work that is grotesque, like Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death,” in which everyone in the story dies of plague, may not register as beautiful but it may register as sublime.

Beyond these Kantian categories, we usually link critical discourse with movements or theories. Movements are shifts in arts and culture that get labels such as neoclassicism, romanticism, and modernism. Theories include New Criticism, reader response, and new historicism. Each movement and theory uses a different set of principles and values about quality (and there is often considerable disagreement within each movement and theory about these principles and values). A work that is “good” according to one theory may be bad in terms of another! To write criticism, you need to familiarize yourself with the concepts and criteria of a movement or theory and become adept at applying these concepts to literary works.

Just as critics evaluate literary works, critics also evaluate other works of criticism. One critic might say that another critic’s work is superficial, malicious, or just wrong. As a critic, you need to state your criteria explicitly. These criteria should apply not just to one work but to other works too – whether all literary works, works of the same genre, or works with similar purposes. For instance, you might claim that a good short story would be one that is relatable and has tension. Then you need to justify those criteria. Another critic might argue with the ones you provide and offer different ones. You need to be able to defend the criteria you provide.

Case Study: Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro”

Case Study: Pound’s “In a Station of the Metro”

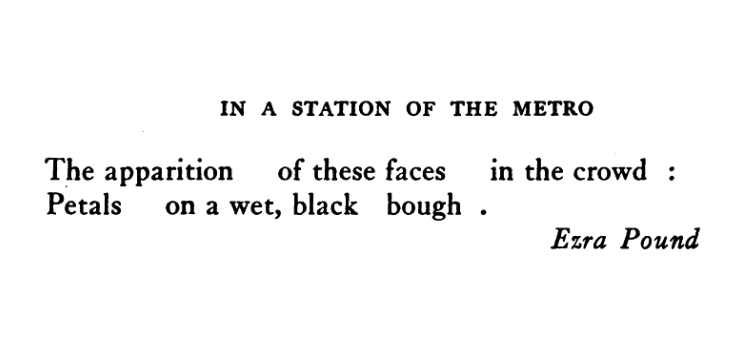

Let’s look at a famous poem by Ezra Pound that critics generally rate as extremely good and significant. The poem is very short – two lines (or three, if you include the title) – and Pound wrote his own piece of criticism about his work, explaining how the final version improved upon an earlier version.

On “In a Station of the Metro”

Ezra Pound (from Gaudier-Brzeska, 1916)

Three years ago in Paris I got out of a “metro” train at La Concorde, and saw suddenly a beautiful face, and then another and another, and then a beautiful child’s face, and then another beautiful woman, and I tried all that day to find words for what this had meant to me, and I could not find any words that seemed to me worthy, or as lovely as that sudden emotion. And that evening, as I went home along the Rue Raynouard, I was still trying and I found, suddenly, the expression. I do not mean that I found words, but there came an equation . . . not in speech, but in little splotches of colour. It was just that – a “pattern,” or hardly a pattern, if by “pattern” you mean something with a “repeat” in it. But it was a word, the beginning, for me, of a language in colour. I do not mean that I was unfamiliar with the kindergarten stories about colours being like tones in music. I think that sort of thing is nonsense. If you try to make notes permanently correspond with particular colours, it is like tying narrow meanings to symbols.

That evening, in the Rue Raynouard, I realized quite vividly that if I were a painter, or if I had, often, that kind of emotion, of even if I had the energy to get paints and brushes and keep at it, I might found a new school of painting that would speak only by arrangements in colour.

And so, when I came to read Kandinsky’s chapter on the language of form and colour, I found little that was new to me. I only felt that someone else understood what I understood, and had written it out very clearly. It seems quite natural to me that an artist should have just as much pleasure in an arrangement of planes or in a pattern of figures, as in painting portraits of fine ladies, or in portraying the Mother of God as the symbolists bid us.

When I find people ridiculing the new arts, or making fun of the clumsy odd terms that we use in trying to talk of them amongst ourselves; when they laugh at our talking about the “ice-block quality” in Picasso, I think it is only because they do not know what thought is like, and they are familiar only with argument and gibe and opinion. That is to say, they can only enjoy what they have been brought up to consider enjoyable, or what some essayist has talked about in mellifluous phrases. They think only “the shells of thought,” as de Gourmont calls them; the thoughts that have been already thought out by others.

Any mind that is worth calling a mind must have needs beyond the existing categories of language, just as a painter must have pigments or shades more numerous than the existing names of the colours.

Perhaps this is enough to explain the words in my “Vortex”: —

“Every concept, every emotion, presents itself to the vivid consciousness in some primary form. It belongs to the art of this form.”

That is to say, my experience in Paris should have gone into paint. If instead of colour I had perceived sound or planes in relation, I should have expressed it in music or in sculpture. Colour was, in that instance, the “primary pigment”; I mean that it was the first adequate equation that came into consciousness. The Vorticist uses the “primary pigment.” Vorticism is art before it has spread itself into flaccidity, into elaboration and secondary application.

What I have said of one vorticist art can be transposed for another vorticist art. But let me go on then with my own branch of vorticism, about which I can probably speak with greater clarity. All poetic language is the language of exploration. Since the beginning of bad writing, writers have used images as ornaments. The point of Imagisme is that it does not use images as ornaments. The image is itself the speech. The image is the word beyond formulated language.

I once saw a small child go to an electric light switch as say, “Mamma, can I open the light?” She was using the age-old language of exploration, the language of art. It was a sort of metaphor, but she was not using it as ornamentation.

One is tired of ornamentations, they are all a trick, and any sharp person can learn them.

The Japanese have had the sense of exploration. They have understood the beauty of this sort of knowing. A Chinaman [sic] said long ago that if a man can’t say what he has to say in twelve lines he had better keep quiet. The Japanese have evolved the still shorter form of the hokku.

“The fallen blossom flies back to its branch:

A butterfly.”

That is the substance of a very well-known hokku. Victor Plarr tells me that once, when he was walking over snow with a Japanese naval officer, they came to a place where a cat had crossed the path, and the officer said,” Stop, I am making a poem.” Which poem was, roughly, as follows: —

“The footsteps of the cat upon the snow:

(are like) plum-blossoms.”

The words “are like” would not occur in the original, but I add them for clarity.

The “one image poem” is a form of super-position, that is to say, it is one idea set on top of another. I found it useful in getting out of the impasse in which I had been left by my metro emotion. I wrote a thirty-line poem, and destroyed it because it was what we call work “of second intensity.” Six months later I made a poem half that length; a year later I made the following hokku-like sentence: —

“The apparition of these faces in the crowd:

Petals, on a wet, black bough.”

I dare say it is meaningless unless one has drifted into a certain vein of thought. In a poem of this sort one is trying to record the precise instant when a thing outward and objective transforms itself, or darts into a thing inward and subjective.

Notice that in Pound’s commentary on his poem, he uses words that we typically use to evaluate things: words like “beautiful,” “vividly,” “pleasure,” “adequate,” and “bad.” When he describes his first attempt to write a poem that captured the feeling he had in the Metro, he critiques it as being a work “of second intensity.” It was Pound’s dissatisfaction with his own efforts that led him to keep going until he was satisfied with his work. Only at that point of satisfaction did he consider his poem to be finished.

Notice too that Pound criticizes other people for what he considers to be their inability to adequately critique what is new in art.

When I find people ridiculing the new arts, or making fun of the clumsy odd terms that we use in trying to talk of them amongst ourselves; when they laugh at our talking about the “ice-block quality” in Picasso, I think it is only because they do not know what thought is like, and they are familiar only with argument and gibe and opinion. That is to say, they can only enjoy what they have been brought up to consider enjoyable, or what some essayist has talked about in mellifluous phrases. They think only “the shells of thought,” as de Gourmont calls them; the thoughts that have been already thought out by others.

Here Pound is disagreeing with the critics who fault the art he likes; he basically says, “they don’t get it – because they are stuck in their old habits.”

Notice too that Pound is naming the kind of art he likes, referring to it as Imagism and Vorticism. By doing so, he is creating not just the categories of new art; he is also creating the language necessary to critique that art.

Pound is teaching us a valuable lesson here; the artist and the critic are partners working together to help audiences appreciate works of art. Sometimes this partnership exists within the same person (here, Pound assumes the roles of both poet and critic), and sometimes they are assumed by different people, as was the case with the critic Cleanth Brooks and the author William Faulkner.

The Stakes of Criticism

The Stakes of Criticism

Good critics are good teachers. They perform a valuable role by helping writers and readers distinguish between good and bad literature. We might consider some literature to be “bad” because it doesn’t have a clear purpose, or because it aims for a bad purpose (such as misleading people). It can be bad because it has a good purpose but doesn’t achieve its aim; we might say of such works that the idea is ok but the writer failed in the execution.

For much of its early history, criticism was taught as a set of universal standards. Aristotle, one of the earliest and most important literary theorists, wrote a book called The Poetics. “Poetics” means “making,” and what Aristotle was aiming for was an account of how literature was made. The Poetics consisted of four smaller books on different literary genres: tragedy, comedy, epic and lyric. Of the original four, only three remain (the book on the comic genre was lost sometime in the middle ages).

While Aristotle’s Poetics appears to be mostly descriptive – accounting for the forms and functions of the various genres – many of the literary writers and critics who followed him used his work prescriptively. In other words, they used it to determine what was good literature (i.e., whatever adhered to Aristotle’s theory) and what was bad literature (i.e., whatever deviated from it) and encouraged writers to stick to the formulas.

Shifting from theory to criticism – in which the descriptive becomes prescriptive – is common in the field of literary studies. While it has helped writers and readers better understand literary arts, a problem with this approach is that it can result in the rejection of new works that don’t fit the constraints set by the theory. The long history of criticism in recent centuries has led to innovations, such as the appreciation of genres – like novels, short stories, and essays – that hadn’t yet been invented in Aristotle’s time, and shifted from “universal principles” of criticism to more situated ones.

This shift away from universalism resulted from a recognition that literature was not produced and consumed solely by a monolithic dominant culture, but also by people who had been historically marginalized. The literary “canon” – what is assumed to be the “best/most important” literature – has been expanded to include works by women authors, LGBTQ+ authors, and non-European and non-white authors. Key to the expansion of the literary canon was the work of critics who argued passionately that the standards of literary quality that had prevailed was, intentionally or not, excluding literature by these writers. New standards had to be articulated: ones that situated the writing of various cultures in their own terms.

The literary canon is a hotly contested subject because there is only so much room in it. The canon consists of works that are routinely included in anthologies and textbooks and in literature classes. A whole field of experts – scholars, critics, editors and publishers, teachers, and administrators – determines what is and isn’t in the canon. They present their cases for what should be included, excluded, added, or subtracted.

The argument over the canon is a very high stakes one, but not all literary criticism is about the canon. Criticism aims to shift our valuation of a literary work: to appreciate its virtues or to be wary of its shortcomings. Good criticism opens our minds to new possibilities for literature in general, and not just for a particular literary work. It is a key part of the literary world.

Steps to Criticism

Steps to Criticism

The first thing a critic must do is establish criteria, which are standards of quality. Standards are words that denote particular qualities, which we put into columns that indicate good or bad – or better or worse. We can adopt critical standards from others, or we can make our own. Either way, we have to explain why we chose those standards and not others. Many critics begin their essays by contrasting their critical approach with those of another critic; they do so to establish that their critical approach has advantages over the other one. In other words, critics criticize other critics!

We might compare the work of the literary critic to that of a food critic. All food critics have standards about what is bad food (i.e., food that tastes so unpleasant that it is inedible) and what is good food (i.e., delicious!). Of course, food critics don’t just say “unpleasant” or “delicious” and call it a day. They use lots of words to indicate why something tastes unpleasant or delicious. And they use different criteria for different things; for instance, they have different standards for desserts than for salads. We don’t want to evaluate a salad by saying that it fails as a dessert (unless it was intended as a dessert).

Different cultures have their own standards for taste. For instance, in European cultures, insects are normally considered to be inedible. Yet 80% of the world’s population eats insects and people have criteria for what counts as the most delicious insects and the most delicious ways of preparing them. We don’t have to change our minds just because someone else likes something that we don’t, but we can learn that standards vary – and that people may heave excellent reasons for keeping those standards. In the next section of this chapter, we discuss intercultural competence, which is how we learn to shift perspectives and understand the values held by people with different cultural experiences.

The late 19th century English critic Matthew Arnold championed literary works that had “sweetness and light,” by which he meant beauty and intelligence. Such writing is likely to please most people. But one thing to know about literary criticism is that lots of “unpleasant” writing has earned praise from one literary critic or another. For example, the 20th century critic and author, Georges Bataille, praised writing that he called “heterogenous,” which he defined as non-productive, excessive, and “unassimilable” (which means something like “inedible”). His point was that such writing presented us with important knowledge about the world and about life. His own writing strikes most readers as scandalous and morbid, but his criticism explains and justifies his choices. Again, we don’t have to like it, but it helps to understand the claims he is making.

The second thing a critic needs to do is apply the critical standards to a case study: a particular literary work (or works). Criticism is often comparative, meaning that the critic will evaluate two or more works and discuss important qualitative differences between them. The critic will explain what a text does well and what it doesn’t do well, according to the critical standards.

Ultimately, the critic reminds the reader why they chose or invented the critical standards and why other critics should adopt them. It also explains why literature in general would improve if writers followed these criteria and why it would deteriorate if they don’t.

Sample Criticism

Sample Criticism

r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r

who a)s w(e loo)k upnowgath PPEGORHRASS eringint(o- aThe):l eA !p: S a (r rIvInG .gRrEaPsPhOs) to rea(be)rran(com)gi(e)ngly ,grasshopper;

How do we crItique a poem like “r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r”? At first glance it looks like an incomprehensible mess. Maybe we should give it an “F” and say it is a bad poem because it makes no sense. But doing so would be a mistake. What if we assume the poem does make sense, but not in the ways that are familiar to us? Let’s assume, for now, that Cummings is challenging the way we make sense of poems (and maybe of the world). We can use the criteria from Victor Shklovsky then, who argued that literature should defamiliarize the world by slowing down our perception. In Shklovsky’s view, a “good” literary work is one that increases our awareness of perception. I will argue that “r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r” does that and is thus a good poem.

We still need to know what Cummings is defamiliarizing and how he is doing it. It seems he is doing two things at once:

- Defamiliarizing poetry itself and how we read it.

- Defamiliarizing an experience that the poet had and sharing it with his readers.

On the first point, we are used to poems that we can read out loud. Perhaps we can read “r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r” out loud, but it presents numerous difficulties. For the title, do we read each letter separately or try to pronounce it as a word? What do we do with all the blank spaces? Do we pause our reading when we come to them? What do we do with “!p:”; do we say “exclamation point, p, colon”? What do we do with “rea(be)rran(com)gi(e)ngly”? Two words are mingled here: “rearrangingly” (which is not a common adverb) and “become.” Should we speak them as one word or as two separate words? The last line of the poem is “,grasshopper;” – it seems to ground the poem because we can now identify a subject (or at least a provisional one). The title of the poem now makes sense – “r-p-o-p-h-e-s-s-a-g-r” is grasshopper with the letters rearranged. Now the word “rearrangingly” makes some sense. Cummings is rearranging the spelling of the word grasshopper for the title. But why?

To answer that question we need to turn to the second point, about Cummings’ experiences. The poet (along with at least one other person) had an experience in which a grasshopper leapt near him. At first he was surprised by its movement and didn’t know what it was. There was a brief moment before he was able to identify it as a grasshopper. The interim – the moment where he experienced it without knowing what it was – is the experience of defamiliarization that he wished to capture and communicate in his poem. The poem is not about the grasshopper leaping. It is about the poet experiencing a variety of sense experiences before identifying what it is or what it means. The apparent disorder of the poem simulates the experience of surprise followed by recognition.

Because Cummings’ poem successfully combines two kinds of defamiliarization – of the world and of poetry – it stands as a lesson in the power of poetry and the need for poets to continue to innovate and find new ways to defamiliarize both our experiences of the world and of poetry itself.

Takeaways: Key Points about Literary Criticism

Takeaways: Key Points about Literary Criticism

- Critics go beyond telling us about a literary work. They make arguments about the quality of a literary work using evaluative terms.

- To do criticism requires that we establish criteria: the standards by which we evaluate literary works. Critics must also justify their choice of criteria, arguing why it is preferable over another choice.

- Criteria relate to particular literary theories or movements within literary arts.

- Criteria may vary depending on the kind of the literary work being evaluated.

- Criticism can be high stakes (for example, about what should be included in the literary canon) or low stakes.

- Criticism must apply the criteria rigorously to a case study (a work of literature) or do a comparative study of two or more works of literature.

- The critic should remind readers why their chosen criteria has advantages for other critics and for literary authors.

Exercise

Exercise

- Make a critique of the literary work below, a literary anecdote by Walter Benjamin, who was an early 20th century German-Jewish writer. What critical standards will you use? What do you need to know about Benjamin’s writing to adequately critique it?

- Brief note: The Benjamin story seems to conceal as much as it reveals. There was an actual historical context for the story; Benjamin had gone to Riga, Latvia to meet Asja Lacis (who directed a children’s theater), but didn’t let her know he was coming. Both Walter and Asja were married to other people. Also, there had been actual shooting in Riga recently. Notice that the main “action” of the story – the narrator seeing the woman or she seeing him – is in the conditional verb tense, meaning it might happen but has not actually happened.

“Ordnance” Walter Benjamin

I had arrived in Riga to visit a woman friend. Her house, the town, the language were unfamiliar to me. Nobody was expecting me, no one knew me. For two hours I walked the streets in solitude. Never again have I seen them so. From every gate a flame darted, each cornerstone sprayed sparks, and every streetcar came toward me like a fire engine. For she might have stepped out of the gateway, around the corner, been sitting in the streetcar. But of the two of us I had to be, at any price, the first to see the other. For had she touched me with the match of her eyes, I should have gone up like a magazine.