EME6613

Intro | CRT | Selecting | Conventional | Comparison | Performance | Charts | Summary

Introduction

How often have you taken a test and wondered, “where in the %^#@$! did that question come from?” Or, how many times have you worked hard on a paper or report, only to get it back with few remarks and little to no indication of how your grade was derived? Such problems occur because educators frequently define objectives, prepare lessons and construct assessments in isolation. Too often, only cursory consideration is given as to how these three critical elements are related.

As mentioned earlier, one of the most important principles of systematic design is that the outputs of one task are used as inputs to the next task. Preceding design decisions inform proceeding design decisions. In this case, the nature of the performance objectives determines how learner achievement of those objectives are measured.

Determining learner assessments at this point in the process may seem out of sequence, however, doing so helps ensure congruence between these two essential instructional elements. There should be a direct correlation between specified objectives and the items used to assess achievement of those objectives. If an objective states that learners should be able to list fifty states, the corresponding assessment should ask learners to list fifty states. Similarly, if an objective states that learners should be able to analyze a case, the corresponding assessment should evaluate learners ability to analyze a case.

Assessment is the process of collecting and analyzing information used to measure individual student learning and performance. When determining learner assessment methods, designers should make sure that they are:

- aligned with performance objectives;

- capable of accurately measuring desired goals/outcomes;

- appropriate for the learners;

- viewed as an instructional tool;

- on-going and a natural part of instruction;

- a shared responsibility between the student, teacher, and peers; and

- include both formal (graded) and informal (non-graded) assessments.

The two common methods used to assess student achievement are norm-referenced and criterion-referenced tests. Educators and instructional designers typically do NOT prepare norm-referenced tests. Norm-referenced tests (NRT) are written by full-time professional test writers, measure general ability levels (e.g., Stanford-Binet) and require very large populations to design. In short, norm-referenced tests compare an individual’s ability to that of a larger population or norm group. In contrast, criterion-referenced tests (CRT) measure student achievement of an explicit set of objectives or criteria.

First, let’s examine various types of CRTs and guidelines for selecting the appropriate assessment method. We will then look at conventional (multiple-choice, true/false, short answer) and performance-oriented CRTs (i.e., checklists and portfolio assessment rubrics) in greater detail. We’ll end by comparing a design evaluation chart (posited by Dick, Carey, and Carey, 2015) to an assessment alignment chart that we recommend (and you are required to complete) for your course project.

[top]

Criterion-Referenced Tests

Criterion-referenced tests are important in testing and evaluating students’ progress and providing information about the effectiveness of the instruction. Dick, Carey, and Carey (2015) note three basic purposes for implementing criterion-referenced tests:

- to inform the instructor how well learners achieved specified objectives;

- to indicate to the instructional designer exactly what components worked well and which ones need revision; and

- to enable learners to reflect on and improve their own performance.

Types of Tests

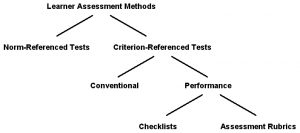

Figure 5.1 illustrates the relationship among the various types of learner assessments. During the Introduction, we noted two basic forms of testing, criterion-referenced tests (CRTs) and norm-referenced tests (NRTs). In the unit Overview, we also indicated that there were two basic approaches to CRTs: conventional and performance. There are also several types of performance-oriented tests, including performance and product checklists and assessment rubrics.

Dick, Carey, and Carey (2015) also identify four uses of CRT: (entry-behavior tests, pretests, practice tests, and posttests). Entry behavior tests measure learners’ mastery of prerequisite skills and knowledge as specified by an instructional analysis (beneath the dotted line) and a context analysis. In comparison, pretests determine learners’ mastery of skills that are to be taught during the instruction. Practice tests help instructors monitor, and help learners assess their progress toward objectives. Posttests, administered after the instruction are designed to test learner achievement of instructional objectives. Posttests are also useful in helping identify areas of the instruction that are may not be working and needs revising.

The course textbook does an excellent job elaborating on these four uses so we won’t discuss them in any further here, except to say that it is important for you to be able to distinguish and apply entry-behavior tests, pretests, practice tests, and posttests when appropriate. So, please be sure to review relevant pages in the course textbook and ask if you have any questions. Selecting the appropriate testing technique requires the consideration of a number of factors.

Selecting an Appropriate Assessment Method

To determine the appropriate learner assessment method (in other words, the correct type of criterion-referenced test items to use), the most important factor to consider is the desired learning outcome(s) (aka. goals and objectives). The type(s) of items used in a criterion-referenced test should be based on the nature of the specified objectives. This is done by looking at the verb or learning task described in the objective.

Objectives that ask students to match, list, describe or perform require different item formats and responses. If the objective asks students to “match,” obviously matching and/or multiple choice items are probably the most appropriate. Table 5.2 lists the basic types of criterion-referenced test items and matches them to related objectives.

Table 5.2 Alignment between item types and learning objectives

|

Method |

Type of Test Item |

Sample Behaviors |

|

Conventional

|

True/False |

identify, recognize, select, choose |

|

Matching |

identify, recognize, select, discriminate, locate | |

|

Fill-in-the-Blank |

state, identify, discuss, define, solve, develop, locate, construct, generate | |

|

Multiple Choice |

identify, recognize, select, discriminate, solve, locate, choose | |

|

Short Answer |

state, name, define, identify, discriminate, select, locate, evaluate, judge, solve | |

|

Essay |

evaluate, judge, solve, discuss, develop, construct, generate | |

|

Performance

|

Performance/Product Checklists |

solve, develop, locate, construct, generate, perform, operate |

|

Assessment Rubric |

construct, generate, operate, perform, choose |

Another similar approach, that we most frequently use to select or recommend learner assessment methods, is based on learning domains (Table 5.3). Using Gagne’s learning taxonomy, we believe that:

- Verbal information and concept learning are best assessed using conventional criterion-referenced testing methods;

- Rules, procedures, and psychomotor skills are best assessed using performance or product checklists; and

- Problem-solving and cognitive strategies are best assessed with assessment rubrics.

Table 5.3 Alignment between assessment methods, type, and learning domains

|

Method |

Type of Test Item |

Learning Domain |

|

Conventional |

True/False |

Verbal Information |

|

Matching |

||

|

Fill-in-the-Blank |

||

|

Multiple Choice |

||

|

Performance |

Performance/Product Checklists

|

Procedures/Rules |

|

Assessment Rubric |

Problem Solving/Cognitive Strategies |

You may have noticed that in comparison to Table 5.2, we left two basic types of conventional test items (i.e., short answer and essay) out of Table 5.3. Can you think of why?

First, we believe short answers may effectively assess the learning of verbal information, concepts, procedures, and rules, and thus, would not fit neatly into the table as currently configured.

Second, and more importantly, we believe that essays, and to a lesser extent, short answers, may be used to assess higher-order thinking skills (e.g., problem-solving and cognitive strategies). However, when they are used for such purposes, they should be accompanied by a checklist or an assessment rubric. In other words, if you ask learners to prepare a short answer or an essay, you should also present criteria that clearly distinguish appropriate from inappropriate performances.

What constitutes an excellent, acceptable, and unacceptable essay? What specific points are you looking for in a short answer? We think it is only fair that the answers to these questions are made explicit before learners are asked to demonstrate their skills and knowledge. Informing or working with learners to define performance criteria will also help them assess their own work or the work of others; an ability that also distinguishes experts from novices.

After you’ve selected appropriate learner assessment methods, attention must be placed on preparing well-written assessment instruments. First, let’s look at guidelines for writing conventional CRTs. Then, we’ll compare conventional and performance CRTs, and conclude by detailing performance/product checklists and portfolio assessment methods.

Conventional CRTs

Dick, Carey, and Carey (2015) posit four criteria for writing assessment items. Table 5.4 lists key considerations associated with each category.

Table 5.4 Key criteria and considerations for writing assessment items

Goal-Centered Criteria

Learner-Centered Criteria

Context-Centered Criteria

Assessment-Centered Criteria

|

As noted by Dick, Carey, and Carey (2009), there are many rules for formatting each type of test item. For example, well-written multiple choice test items demonstrate the following characteristics:

- Stem clearly formulates problem (worded so that learner can easily determine what problem or question is being asked before reading possible answers).

- Task and most information contained in stem, keeping answers/options short.

- Stem includes only required information and written in clear, positive manner

- Foils includes only one correct, defensible, best answer.

- Foils are plausible and do not contain unintentional clues to correct answer (e.g., length, “all,” “never,” “a,” “an”).

In addition, Dick, Carey, and Carey (2009) discuss factors to consider when determining mastery criteria, sequencing items, writing directions, and evaluating tests and test items. They also describe procedures for developing instruments to measure performances, products, and attitudes and provide examples of assessment items and instruments. These concepts should also be applied as you design learner assessment instruments for your instructional unit.

Dick, Carey and Carey (2009) do a good job discussing key concepts associated with conventional criterion-referenced testing which is why I only noted them (above). However, they spend relatively little time detailing factors associated with performance-oriented measures. For the remainder of this unit, we will turn my attention to the development of performance-based assessments.

[top]

Conventional vs. Performance Assessments

Conventional assessment methods include fill-in-the-blank, short answer, multiple-choice, matching, and true/false test items. They are relatively easy to score and when designed properly, can provide a reliable and valid means for assessing students’ acquisition of skills and knowledge.

As advocates pointed out, conventional tests can be mass-produced, administered, and scored, and provide the quintessential sorting criterion – a score that had the same meaning for every student who took the same test. It offered empirical support for the sorting function of schools.

However, in the mid-1980s, it became apparent that if all schools do is rank students, those in the bottom third of the distribution have no way to contribute to society. These students were labeled “at risk” of dropping out of school. Further, employers began to note that grade-point averages and class rank failed to assure that newly hired employees could read, write, work in teams, solve problems, or bring a strong work ethic to the job. Colleges, wanting to provide programs to meet specific student needs, required more information than just comparative achievement scores. These forces brought many educators to realize that schools must do more than sort students. Educators began to explore the potential of performance assessments.

This is not to say that conventional CRTs are inappropriate. Rather, the exclusive use of conventional CRTs may be insufficient. Conventional CRTs can be an effective and efficient method for assessing learners’ acquisition of skills and knowledge. However, they may be insufficient for measuring learners’ ability to apply skills and knowledge. Table 5.5 illustrates the differences between conventional assessments and performance-based assessments.

Table 5.5. Comparison of conventional and performance assessments

|

Conventional CRT |

Performance-Based CRT |

| Criteria are often vague and unclear | Criteria are explicit and public |

| Used to rank and sort students | Used as an integral part of learning |

| Tests acquisition of skills and knowledge | Tests application of skills and knowledge |

| One-dimensional and episodic; only tests skills and knowledge at a specific time and place | Multidimensional and over time tests development of skills and knowledge across situations |

Educators are now attempting to learn about this “new” assessment method. Recent applications carry such labels as authentic assessment, alternative assessment, exhibitions, and student work samples. Performance assessments, however, are not new. They are not radical inventions recently discovered by critics of traditional testing. Rather, they are a proven method of evaluating human characteristics that have been the focus of research in both educational settings and in the workplace for some time (Berk, 1986; Linquist, 1951). The challenge is to make assessments more reliable, cost-effective, and able to meet measurement standards.

[top]

Performance Assessments

Performance assessments call for students to demonstrate what they are able to do with their knowledge. Performance assessments allow observation of student behaviors ranging from individual products or demonstrations, to work collected over time. These types of instruments typically do not involve conventional “test” items. Instead, instruments for performance assessments have two basic components: a clearly defined task, and a list of explicit criteria for assessing the performance or product. The defined task includes clear directions to guide learners’ activities. The assessment criteria are also used to guide peer, teacher, and learner evaluations. It is important that the criteria focus on specific behaviors described in the objectives that are both measurable and observable.

Performance or Product Checklists

Product and performance checklists represent one form of performance assessment described by Dick, Carey, and Carey (2009) that is appropriate for measuring learners’ ability to apply relatively simple procedures, perform psychomotor skills or develop relatively straightforward work samples. In other words, checklists are appropriate when there is typically one correct way of applying a procedure, performing a psychomotor skill, or deriving a correct answer. Table 5.6 presents a template for either a performance or product checklist. Additional examples are provided in the course textbook.

Table 5.6 Template for product or performance checklist

| Product/Performance: | |||

|

Criteria

|

Meets Criteria?

|

Comments

|

|

|

Yes

|

No

|

||

Dick, Carey and Carey (2009) discuss additional guidelines for developing instruments that measure performances, products and attitudes in the course textbook. You will read about two additional response formats: rating scales and frequency counts. The use of frequency counts are relatively rare, but as Dick, Carey and Carey note, may be useful when a criterion to be observed can be repeated several times. Rating scales may be useful if there are more than two distinct levels of performance, but in such cases, we prefer the use of assessment rubrics as discussed below.

Portfolio Assessments

Another format for performance-based assessment is portfolio assessment. Student portfolios typically contain:

- Work samples that demonstrate achievement of the targeted goals and objectives. These samples show the student’s ability to apply the skills and knowledge.

- Narrative that describes how the work samples demonstrate achievement of specified criteria. It is important for students to explain how and why their chosen samples meet performance standards. This also allows students to reflect on their learning.

- Performance standards and assessment rubrics to evaluate achievement level. This helps students determine if their work samples meet defined performance criteria.

Student Work Samples

Student work samples for portfolios can include a variety of products. Types of products include, but are not limited to:

|

|

Student Narratives

Students’ narrative description of their portfolio should: (a) state their goals for the class; (b) describe their efforts to obtain goals; (c) explain how each of their work samples demonstrates achievement of the goals, and (d) reflect on their experience (e.g., self-assessment of what and how they learned, what more they need/want to learn). The narrative may be presented as a separate section of a student’s portfolio, or it may be woven into their portfolio.

Performance Standards and Assessment Rubrics

When defining performance standards and assessment rubrics, you must take into consideration both the Scoring Criteria and Method.

Scoring Criteria. Assessment rubrics are the general format for criteria used to assess portfolios. Assessment rubrics contain both descriptors and a scale that defines the range of performance. The descriptors are written descriptions of the range of performance levels. These descriptions: (a) communicate the standards for the product or performance; (b) are derived from the stated performance objectives; (c) link the curriculum and assessment; and (d) provide for student self-assessment. The scale for the rubric consists of the quantitative values that correspond to the descriptors. Table 5.7 depicts the descriptor and related score for various levels of leaping ability.

Table 5.7 Scoring criteria for assessing leaping ability

|

||||||||||||

|

Scoring Methods. Specific scoring methods for rubrics are either analytic or holistic in nature. The analytic, or point scoring method focuses on specific work samples and separate scores based on different dimensions or components of work. The holistic or global scoring method bases scores on an overall impression of the portfolio or compilation of work samples.

The analytic scoring method provides assessment rubrics and points scores for specific work samples. If you were to apply the analytic method, you would create an assessment rubric for each type of work sample produced by students and included in their portfolios. You would compare each work sample to its related rubric and determine students’ level of achievement. You can then aggregate scores to determine students’ grades for a course or unit of instruction. More importantly, the assessments of student work samples should serve as a diagnostic tool to provide students with profiles of their emerging abilities to help them become increasingly independent learners. The basic components of an analytic rubric are:

- Performance Levels – the range of various criterion levels

- Descriptors – standards of excellence for the specified performance levels

- Scale – a range of values used for each performance level

Table 5.8 provides a template for preparing an analytic Assessment Rubric. Table 5.9 provides an example of a completed analytic Assessment Rubric for a research paper.

Table 5.8 Assessment Rubric for a specific product or performance

|

Performance Level 1

(scale/point range) |

|

|

Performance Level 2

(scale/point range) |

|

|

Performance Level 3

(scale/point range) |

|

Table 5.9 Example Assessment Rubric for Research Papers

|

Distinguished

(90-100 pts) |

|

|

Proficient

(80-89 pts) |

|

|

Satisfactory

(70-79 pts) |

|

|

Unsatisfactory

(<70 pts) |

|

Holistic scoring methods differ from analytic techniques in that they provide one general score for a compilation of work samples rather than individual scores for specific work samples. They focus on more general proficiencies or performance standards and allow students to select different work samples to demonstrate achievement of the standards. If you were to apply the holistic method, you would define performance standards for a particular program, course, or unit of instruction. For example, for an introductory computer course, you may define performance standards related to basic operations, use of productivity tools, multimedia tools, and telecommunication tools. You would then create an assessment rubric for each standard that includes each standard.

Students would generate and submit work samples to demonstrate achievement of each standard and you would compare students’ selected work to the rubric to determine students’ level of achievement. The resulting score may be used to determine students’ grade for the course or unit of instruction. More importantly, the assessments should serve as a diagnostic tool to provide students with profiles of their emerging abilities to help them become increasingly independent learners. The basic components of the holistic assessment rubric are:

- Performance Standard – description of the performance being assessed

- Performance Levels – the range of various criterion levels

- Descriptors – standards of excellence for the specified performance levels

Table 5.10 provides a template for preparing a holistic Assessment Rubric. Table 5.11 provides an example of a completed holistic Assessment Rubric for using basic productivity software tools.

Table 5.10 Holistic portfolio assessment rubric

|

Performance Standard |

Performance Levels

|

||

|

Performance Level 1 |

Performance Level 2 |

Performance Level 3 |

|

|

Description |

|

|

|

Table 5.11 Holistic rubric for an instructional unit on a productivity software

|

Performance |

Performance Levels

|

||

|

Novice User |

Intermediate User |

Advanced User |

|

|

Use of Productivity Tools |

Little to no knowledge of the availability or the basic functions and features of various productivity tools.

Little to no knowledge of instructional strategies for integrating productivity tools with instruction. Requires significant amounts of help to select, locate, run and use productivity tools. |

Utilizes basic features of word processing application to create word-processed document.

Utilizes basic features of database management program to create and manipulate a dbase. Utilizes basic features of spreadsheet application to create and manipulate a spreadsheet. Utilizes basic features of graphics program to create and manipulate a graphic. |

Utilizes advanced features of: word processor, dbase management program, spreadsheet and graphics applications

Combines use of word processor and dbase to create personalized form letters by using mail merge function. Combines word processor with graphics to create documents which contains both texts and graphics (aka. desktop publishing). |

Benchmarks and Training

In addition to work samples, narratives, performance standards and assessment rubrics, educators applying portfolio assessment methods should provide benchmarks and train both evaluators and students on relevant techniques.

Benchmarks are exemplary samples of work or performance used to illustrate in concrete terms, the meaning of each descriptor. These samples are usually in written or quantitative form.

Training should be provided for those who will use the scoring method chosen. Potential problems with using rubrics include that the scoring criteria can be subjective, some question the reliability, and the cost and time involved can be high. Research and experience have shown that proper training on developing rubrics and well as how to use them can eliminate some of the potential problems. Proper training helps lead to explicit and clear criteria as well as high inter-rater reliability when different people use the instrument to assess performance.

[top]

Design Evaluation and Assessment Alignment Charts

A Design Evaluation Chart (e.g., p. 155 of the course textbook) is an excellent tool for ensuring the alignment of your assessment items with your objectives, and the skills and knowledge identified during your instructional analysis. Table 5.12 presents a template for creating a Design Evaluation Chart as prescribed by Dick, Carey and Carey (2015).

Table 5.12 Template for Design Evaluation Chart

|

Skill |

Objective |

Assessment Item |

| Skill 1.0 | Objective 1.0 | Test Item 1 |

| Skill 2.0 | Objective 2.0 | Test Item 2 Test Item 3 |

Column one lists the various skills that were specified in your instructional analysis (verb/statement contained in primary boxes). Column two lists the actual objective constructed for instruction based on the instructional analysis. Column three lists the assessment items that are used to determine learners’ achievement of each objective. Alignment is achieved when the action (aka. skill, behavior) specified across the columns matches.

For the purposes of this course, you are to prepare an Assessment Alignment Chart that is identical in purpose and similar in configuration to a Design Evaluation Chart. The only difference is an Assessment Alignment Chart consists of 5, rather than 3 columns, including additional columns for (a) classifying each objective by learning domain, and (b) depicting the use and type of assessment instrument (aka. assessment method). The additional columns are included to help ensure the selection of appropriate assessment methods based on the classification of each objective (according to Gagne’s domains of learning).

Table 5.13 illustrates the components of a Learner Assessment Alignment Table for the terminal and one enabling objective defined for Unit 1 of this course. Additional enabling objectives, along with related assessments and information are not pictured.

Table 5.13 Sample Learner Assessment Alignment Table

|

Skill

|

Objective

|

Domain

|

Method

|

Item/Criteria

|

|

Self-assess prior knowledge of systematic design

|

1.0 Given a systematic design process, assess your prior skills, knowledge, interests and experiences relative to the topics and tools covered in the course. |

Cognitive Strategy

|

Post-Test: Portfolio Assessment Rubric |

|

|

Identify benefits

|

1.2 Given an instructional situation, students will be able to identify benefits associated with applying systematic design tools and techniques. |

Verbal

Information |

Post-Test: Multiple Choice Quiz |

One of the primary benefits associated with systematic design is that it:

(a) does not take too much time or resources. |

The number of items needed to accurately assess each objective can vary based on the nature of the objective as well as the type of item. Test items that enable students to guess the correct answer should be supplemented with several parallel items that test the same objective. Dick, Carey, and Carey (2009) recommend three or more items for intellectual skills and one item for verbal information if the verbal information involves the simple recall of specific information. If the verbal information covers a wide range of information (e.g. identify the state capitals), a random sample of the information is adequate to show mastery of the objective.

[top]

Summary

Unit 5 covered two types of criterion-reference tests: conventional and performance-based. We reviewed key concepts for developing conventional tests and test items presented by Dick, Carey, and Carey (2009, 2015). We furthered Dick, Carey, and Carey’s discussion of measurement techniques for performances, products, and attitudes by detailing key concepts associated with performance assessments. Specifically, we described three essentials of portfolio assessment (i.e., work samples, narrative, and assessment rubrics) and identified two additional considerations (i.e., benchmarks and training). We then prescribed the development of an Assessment Alignment Chart, rather than a Design Evaluation Chart, to ensure alignment between objectives and assessments.

It is important to remember that performance assessments are not advocated as more appropriate than conventional, criterion-referenced tests. In fact, a conventional multiple-choice, fill-in-the-blank, matching, short answer, and true/false test may be used as an integral part of a portfolio. The key is to develop valid and reliable assessment instruments that are appropriate for measuring the achievement of defined learning objectives.

[top]

Last Updated 08/19/22