EME6613

Where do Goals come from? | Scope | Components | Clarifying | Classifying | Analyzing | Summary

“If you don’t know where you are going, any road will get you there.”

Lewis Carroll – Alice in Wonderland

The famous quote from Alice in Wonderland notes the importance of clearly defining and understanding the instructional goal. An important initial step in the systematic design process is to analyze your instructional goal. The results of a goal analysis (a goal analysis diagram that illustrates the relationship between key components of your goal) will then help you define the scope and sequence of your instruction, including the number, nature and sequence of instructional units to be contained in your course or training program. Unit 1 reviews key concepts covered in Chapters 2 and 3 of the Dick, Carey, and Carey (2015) course textbook. It summarizes approaches for identifying goals, generating goal statements and for analyzing the goal. The end of this supplemental reading further delineates three approaches to goal analysis that may be used to structure your course or training program in fundamentally different ways.

[top]

Where do Instructional Goals come from?

In Chapter 2, Dick, Carey, and Carey (2015) discuss different approaches for identifying instructional goals. For example, the Subject Matter Expert (SME) approach is often quicker and requires fewer resources and thus, is more common than the Performance Technology (PT) approach, but it has its shortfalls. Typically, SMEs base their designs on past learning experiences. They focus on the communication of information from instructor to learner and often emphasize the importance of knowing or understanding content information rather than what the target population must be able to do with the content.

In contrast, a PT approach begins by examining the nature of the performance problem (e.g., by conducting some form of needs assessment) and bases solutions on identified causes of the performance problem rather than assuming that instruction is the best answer. In Chapter 2 of the course textbook, Dick, Carey and Carey (2015) discuss performance analysis, needs assessment and other techniques for establishing instructional goals in further detail. Be sure to review these concepts.

The course EME 6607 Planned Change examines the needs assessment along with non-training interventions in detail. For this course, you are starting with a goal statement that was either (a) pre-defined by a participating organization, or (b) defined by a classmate. Either way, the goal is probably, but not necessarily derived using the SME approach. For the purpose of this course, that is okay. The important thing to keep in mind at this stage is that there are different ways to identify instructional goals (e.g., SME vs. PT (along with their benefits and limitations), realize that instruction is a relatively expensive method for addressing performance problems that should only be applied when other options are unsatisfactory, and focus on learners who must be able to do in real-life context.

If you choose to work with a goal statement defined by a classmate, at least one member of your team must serve as the SME or you should ensure ready access to an SME. If you work with a pre-defined goal statement, the participating organizations has already committed to having a SME available to you throughout the semester. Just remember, we are beginning with the assumption that training or instruction is appropriate. If, in real life, you feel that training may not be the best method for enhancing performance, you should conduct some type of performance analysis (e.g., needs assessment or training needs analysis) to determine the best course of action.

[top]

Scope

The scope of your instructional goal will determine the amount of instruction that will be necessary to achieve the goal. A relatively extensive goal may require a series of workshops or a semester of coursework to accomplish. Less extensive goals may take anywhere from a few hours to a few weeks to attain.

For this course, your group will concentrate on analyzing, designing, developing and formatively evaluating ONE unit of instruction. However, you will begin by defining a relatively extensive instructional goal that may take a series of lessons, workshops or a semester of coursework to achieve. In subsequent chapters, you will focus on analyzing one aspect of your goal and designing and formatively evaluating ONE instructional unit or lesson. Throughout the semester, you will be asked to complete a few assignments at the course level (i.e., goal analysis, learner analysis, context analysis, general formative evaluation plan). However, most of your efforts will concentrate on the unit/lesson level. This approach is taken purposefully so that you can see the similarities and differences between course and lesson level design.

[top]

Key Components

A short goal statement should include a brief description of the learner and targeted skills. In contrast, a complete goal statement provides additional information about the performance context and the availability of tools. Table 1.1 depicts the key components for both short and extended goal statements. Please note; the length of your statement has little to do with the scope of your instruction.

Table 1.1 Comparison of Short and Extended Goal Statements

|

Short Goal Statement |

Description of:

|

|

Extended Goal Statement |

Description of:

|

Both statements are used to focus subsequent analyses. Typically, a short goal statement is presented at the top of goal analysis charts and is used to label ensuing design documents. An extended goal statement is often presented at the beginning of analysis reports and design documents to give readers and potential development team members a complete and common vision of the desired results. A complete goal statement may also be used latter as a course description and for marketing purposes. Table 1.2 provides a sample of a short and complete goal statements for this course.

Table 1.2 Sample Goal Statements for Graduate Course on Systematic Design

|

Short Goal Statement |

Instructional technology graduate students will analyze, design, develop, and formatively evaluate a unit of instruction. |

|

Extended Goal Statement |

Given an instructional situation and access to relevant subject matter expertise, instructional technology graduate students will be able to apply systematic design tools and techniques to analyze, design, develop, and formatively evaluate a unit of instruction that meets published criteria quality instruction. |

[top]

Clarify Fuzzy Goals

Fuzzy goals do not specify what learners can do if they achieve the goal in measurable/observable terms. They typically contain abstract statements of internal learning outcomes like “increase awareness of,” “demonstrate understanding,” and “appreciate.” The goal should be clarified if it is unclear what performances constitute accomplishment of the goal. The goal should also be stated in measurable terms; in other words, using concrete verbs that may be observed. If you can’t measure the goal, how will you ever know if you’ve achieved it? In the course textbook, Dick, Carey, and Carey (2015) refer to Mager’s (1997) (p.26) work on clarifying fuzzy goals. If you think you have a fuzzy goal, be sure to clarify it.

[top]

Classifying Goals

In Chapter 3, Dick, Carey, and Carey (2015) discuss two steps in analyzing goals: (a) classifying the goal according to learning outcome and taxonomy, and (b) identifying and sequencing major steps involved in performing the goal. Dick, Carey and Carey utilize Gagné’s five domains of learning as a foundation for completing these two steps. We extend their discussion by giving you an overview of alternative learning taxonomies so you have a better idea of how they compare. However, please note: You are expected to apply Gagné’s taxonomy throughout the course so please be sure you are able to distinguish each category.

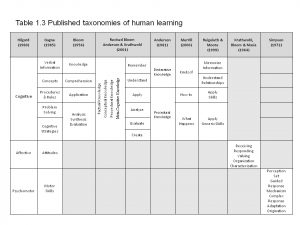

It is believed that learned human capabilities may be classified into several distinct categories. For instance, Bloom proposes what is probably one of the best known learning taxonomies that distinguishes between knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis and evaluation. Others differentiate between cognitive, affective and psychomotor learning outcomes. Table 1.3 Contrast several published learning taxonomies. While comparing the taxonomies, it is important to note that most posit additional subcategories within each major domain.

For this course, you are to apply Gagné’s (1977) five domains of learning. The five domains include:

1. Verbal Information – factual information that is stored or looked up.

2. Intellectual Skills – capability to use symbols to organize, interact with and make sense of the world such as reading, writing, distinguishing, combining, classifying and quantifying.

2.1 Discriminate – distinguish between two stimuli.

2.2 Form concrete and defined concepts – identify stimulus as a member of class having common characteristics and demonstrate meaning of class of objects, events or relations.

2.3 Apply rules – apply principles and follow procedures, responding with regularity over a

variety of situations.2.4 Solve problems – apply combination of rules to solve real or intellectual problems.

3. Cognitive Strategies – capability to govern/direct thinking, learning and remembering.

4. Motor Skills – execute movement in organized motor acts.

5. Attitudes – mental states that influence direction and degree of effort.

It is recognized that the distinction between the domains may be somewhat artificial in real life. The achievement of most goals requires a combination of intellectual and psychomotor skills, verbal information and/or attitudes. For example, playing basketball requires players to shoot, dribble and pass (psychomotor skills), know the rules (verbal information), develop a game strategy (intellectual skill), apply the game strategy (cognitive strategy) and have a strong desire to win (attitudes).

However, it is believed that the distinction between domains facilitates both analysis and design. Classification of the intended goal helps designers select the appropriate analysis technique to identify major steps and subordinate skills and knowledge. During the design phase, classification of the goal and related objectives help designers determine the appropriate instructional strategies to promote goal achievement.

[top]

Three (3) Ways to Analyze your Goal

After defining and classifying your instructional goal, your next task is to analyze it and generate a goal analysis diagram that depicts either (a) major steps necessary to achieve or perform the goal, or (b) simple to complex examples of goal performance. The diagram may then be used to determine the nature, number and sequence of instructional units/lessons to be included in the course or training program.

There are three fundamental ways to analyze an instructional goal, including: (a) a topic or content area approach, (b) a step-wise approach, and (c) an elaboration approach. For the purposes of this course, you should be able to distinguish the three approaches and apply either the step-wise and/or the elaboration approach.

We briefly summarize the content/topic and the step-wise approach and further delineate the elaboration approach (below).

Content Approach

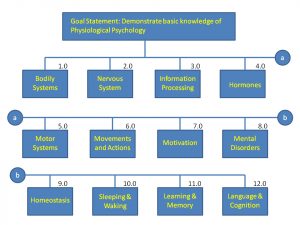

The content approach to goal analysis identifies the major topics to be covered in a course or training program. I’m (fairly) sure you’ve seen it before. Just look at the table of contents of your typical textbook or think back to many of the courses and/or training programs you’ve taken in the past. The content approach focuses on knowing and is typical of how subject matter experts define the scope and sequence of a course or training program. Figure 1.1 depicts the results of a content oriented goal analysis. Generated from an advanced college level biology course, it divides the course into 12 units, each covering a topic related to Physiological Psychology.

Figure 1.1. A topic/content oriented goal analysis of a college biology course

When goals are analyzed in terms of what learners are expected to know, and courses/training programs are divided into topics, learners typically concentrate on one unit (or book chapter) without considering the contents of other units (or book chapters). The instructional materials and resources specified for a unit is used in one block of time, rather than different points throughout a term or program and once the class (or team or individual) moves onto the next topic, the first one is often forgotten. With a content/topic approach to goal analysis and course design, learners often fail to see the relationship between topics or how the skills and knowledge covered in one unit relate to another or to real-life.

Step-wise Approach

In comparison to the content/topic approach, the step-wise and the elaboration approach to goal analysis concentrate on what learners are supposed to do, rather than know. They provide instructional developers with an unambiguous description of what exactly someone would be doing when performing the goal. As noted by Dick, Carey, and Carey (2015), starting the design process by determining what learners are supposed to be able to do as a result of instruction is in sharp contrast to first identifying what topics or content areas are necessary to achieve the goal.

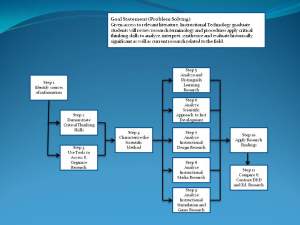

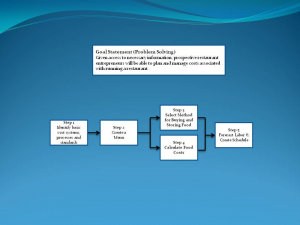

The step-wise approach identifies and sequences the major steps necessary to perform a goal. To identify and sequence major steps, ask yourself what learners need to do in order to perform the goal. Your goal statement may already include a short description of the major steps. Each step may represent a physical activity or a mental step, and the description of each step should include a measurable verb. A goal analysis results in a flow diagram, or visual display, that clearly identifies and illustrates the relationship among the major steps.

Figure 1.2 illustrates the results of a stepwise goal analysis completed for a graduate level course on Instructional Technology Research. The goal analysis diagram identifies and illustrates the relationship between the major steps Instructional Technology graduate students must be able to complete to analyze, interpret, synthesize and evaluate historically significant and current research related to field.

Figure 1.2. Stepwise goal analysis of EME6062 Research in Instructional Technology

Figure 1.3 illustrates the results of a step-wise analysis of a goal specified for a graduate level course on cost control taken by hospitality management students at UCF’s Rosen College. The goal analysis diagram identifies and illustrates the relationship between the major steps Hospitality Management graduate students must be able to plan and manage costs associated with running a restaurant.

Figure 1.3. Step-wise goal analysis of HPT 4467 Cost Controls in Hospitality

Elaboration Approach

In comparison to the step-wise approach, the elaboration approach to goal analysis begins by identifying the simplest epitome of someone performing the goal (also referred to as the whole task or simply as the task). After identifying the simplest epitome of the whole task, the analysis progresses through more complex examples of the goal being performed. In other words, it elaborates on the goal or whole task.

Take, for example, someone preparing a spaghetti dinner. The simplest epitome of the whole task may include the use of pre-made, boxed noodles, bottled spaghetti sauce, frozen garlic bread, and packaged salad with some already grated parmesan cheese. The next most complex iteration of making a spaghetti dinner may focus on adding some fresh ingredients to the bottled spaghetti sauce, and preparing the salad and garlic bread with their basic ingredients. More complex examples of the goal may then include making the sauce, the pasta noodles, and salad dressing from scratch.

Training and education often focuses on complex cognitive tasks. By first presenting learners with a simple epitome of the whole task, they may begin to understand the task holistically and start to acquire the skills necessary to complete a real-life task from the very first lesson. Being presented with and acquiring the skills necessary to accomplish a real-life task at the beginning of a course or training program, in turn, may be more motivating then simply learning the first step of a task. “The holistic understanding of a task [also] results in the formation of a stable cognitive schema to which more complex capabilities and understandings may be assimilated. This is especially valuable for learning a complex cognitive task” (Reigeluth, 1999, p. 433).

To identify simple to complex examples of the goal, ask yourself (and/or work with a SME to determine) what is the simplest epitome of someone demonstrating or performing the goal. Your goal statement may already include a short description of the whole task. Identify the simplest example of the whole task that is fairly representative of the goal and describe the conditions that distinguish it from other versions or examples of the task.

When elaborating a whole task, Reigeluth (1999, p. 445) also suggests that:

“- It may be helpful to start by identifying some of the major versions of the task and the conditions that distinguish when one version is appropriate versus another.

– Thinking of different conditions helps to identify versions, and thinking of different versions helps to identify conditions. Therefore, it is wise to do both simultaneously (or alternately).

– Ask the SME to recall the simplest case [of the whole task] she or he has ever seen. The simplest version will be a class of similar cases. Then check to see how representative it is of the task as a whole.

– There is no single right version to choose. It is usually a matter of trade-offs. The very simplest version of the task is usually not very representative of the task as a whole. The more representative the simple version can be, the better, because it provides a more useful schema to which learners can relate subsequent versions.

– You may want to use some other criteria in addition to simple and representative, such as common (how frequently performed the version of the task is) and safe (how much risk there is to the learner and/or the equipment).”

After identifying the simplest epitome of the whole task that is fairly representative of the goal, work with the SME to identify the next simplest version whole that is more representative for the goal. In general, the next simplest (or more complex) version will require learners to address additional variables and/or more difficult conditions. “Complexity is affected by the number of constituent skills involved, the number of interactions between constituent skills, and the amount of knowledge necessary to perform the constituent skills” (van Merrienboer et al., 2002, p. 44). Continue to identify progressively complex versions of the whole task until instructional time runs out or the learner(s) have reached the desired level of expertise.

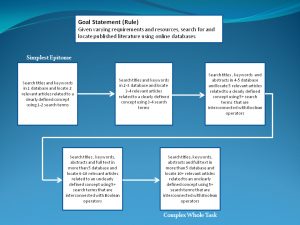

Figure 1.4 depicts the results of an elaborated goal analysis for the task of searching for literature. The goal analysis diagram begins by identifying the simplest epitome of the task that is fairly representative of the goal and progresses through more complex versions of the goal being performed in real-life until the desired level of mastery is achieved.

Figure 1.4. Elaborated goal analysis for the task of searching for literature

Progressively complex versions of a task may be constructed by varying one or more of the conditions related to the task. The simple to complex versions of searching for literature (noted above) were derived by identifying the conditions that make literature searchers more or less complex, as noted by van Merrienboer, Kirschner, and Kester (2003), including the:

(a) clearness of the concept definitions within or between domains (ranging from clear to unclear);

(b) number of articles that are written about the topic (ranging from small to large);

(c) number of domains in which relevant articles have been published and, hence, the number of databases that need to be searched (ranging from one familiar database to many databases that are relevant for the topic of interest);

(d) type of search (ranging from a search on titles and key words to abstracts and full text); and

(e) number of search terms and Boolean operators used (ranging from a few search terms to many search terms that are interconnected with Boolean operators).

For more details on the elaboration and the simple to complex approach to instructional design, see the articles and book chapters by Reigeluth and van Merrienboer et al. listed under the References at the end of this supplement. Additional goal analysis diagrams and detailed procedures for conducting a goal analysis are provided in Chapter 3 (pp. 51-56) of the course textbook.

A question that may arise as you analyze your goal is, “how large should a step be,” or “how much should be included in one step.” There are no easy answers. In general, if instruction is intended for young students, each step in a goal should be rather small. An instructional goal for older students may be broken down into larger steps. In general, it is recommended that you identify between 5-15 steps to achieve your goal.

[top]

Summary

Instructional goal statements should contain a clear, statement of learner outcome(s) and delimit the field of study. When developing a goal statement, attention should be given to the importance/relevance of the course by associating course content with authentic needs and/or proficiencies. An instructional goal statement should be written in terms of what is expected from students, painting a picture of what you want your students to know and be able to do at the end of your course. Analysis of the goal includes the classification of the goal and by either identifying the major steps necessary to perform the goal or by identifying simple to complex versions of the whole task being performed in real-life. A goal analysis diagram illustrates the relationship between the major steps or whole task examples. The purpose is to identify and communicate what learners need to be able to do to accomplish the goal and to determine the scope and sequence of instructional units to be included in a course or training program. This information will be used in the next unit to help identify specific subordinate skills and knowledge that will then be transformed into learning objectives for your instructional unit.

[top]

REFERENCES

van Merrienboer, J. J. G., Clark, R. E., & Croock, M. B. (2002). Blueprints for complex learning: The 4C/ID-model. Educational Technology Research & Development, 50(2), 39-64.

van Merrienboer, J. J. G., & Kester, L. (2007). Whole-task models in education. In J.M. Spector, D. Merrill & J.B. Merienboer, & M. P. Driscoll (Eds). Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology (3rd Ed.) (pp. 441-456). Routledge.

van Merrienboer, J. J. G., Kirschner, P. A., & Kester, L. (2003). Taking the load off a learner’s mind: Instructional design for complex learning. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 5-13.

Reigeluth, C. M. (1999). The Elaboration Theory. In C. M. Reigeluth (Ed.). Instructional-Design Theories and Models: A New Paradigm of Instructional Theory (Volume II) (pp. 425-453). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

[top]

Last Updated 08/19/22