The Cherokee Memorials

The Cherokee Memorials (1829)

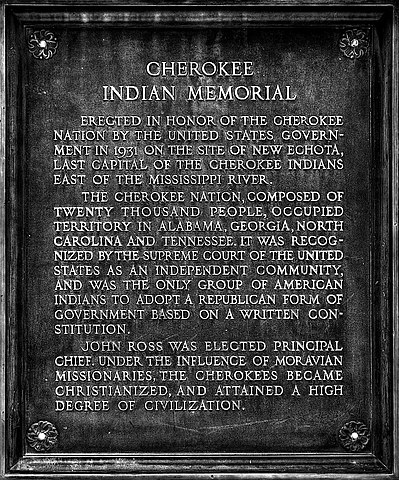

Cherokee Indian Memorial sign at New Echota Historic Site

Introduction

We often think of a “memorial” as something like a “tribute,” but that isn’t quite what it means in this context. As the scholars of American Passages explain:

A direct appeal to Congress, the courts, or another official federal body, a “memorial” was the nineteenth-century equivalent of a petition. The Cherokee tribe produced articulate and compelling memorials asking the United States Congress to allow them to stay in their traditional homelands east of the Mississippi. The Cherokee Council, which was the official leadership body of the tribe, composed its own memorial to send to Congress, while also submitting twelve other memorials written by Cherokee citizens. Despite their eloquence, the Cherokee memorials were not effective and the tribe was relocated in 1838.

Anticipating that they would soon be ordered to “remove” from their homelands, the Cherokee Council composed the Memorials as a direct appeal to the US Congress. Given the context of that moment (Jacksonian Indian Removal policies coupled with the recent discovery of gold on Cherokee lands), it makes sense that the Cherokees would be looking for ways to preserve their nation during a time of upheaval. It might also make sense to us that they were in a precarious position: they are appealing to a large, powerful, and increasingly violent sovereign nation, and part of their argument involves pointing out how that larger, more powerful nation has violated a legal agreement against them. As you read, consider how the Cherokees build their argument, and how they position themselves with respect to their audience. Consider also how this document is structured and how it functions as a legal document. You might also compare it to other early legal documents that you’ve heard of, such as the Mayflower Compact or the US Declaration of Independence.

Discussion Questions:

- How do the Cherokees build their argument? How do they position themselves and their audience? Where do you find them most convincing, and why?

- Examine the Cherokee Memorials in conjunction with other legal documents like the Mayflower Compact (found in William Bradford’s Of Plymouth Plantation) or the Declaration of Independence. What does each document outline? How does each establish what is being agreed upon? How does each address the consequences of violating these agreements?

- Examine the Cherokee Memorials in light of Pratt’s “contact zone” definition.

- How might the Cherokee Memorials be in conversation with texts by other Native writers during this period? In what ways do they engage with the ideas offered by writers like David Cusick, William Apess, or Black Hawk?

- How do the Cherokee Memorials urge us to consider what counts as “American”?

CHEROKEES MEMORIALIZE CONGRESS.

While the negotiations leading up to the conclusion of this treaty were in progress John Ross and his delegation, finding no disposition on the part of the executive authority to enter into a discussion of Cherokee affairs predicated upon any other basis than an abandonment by them of their homes and country east of the Mississippi, presented a memorial to Congress complaining of the injuries done them and praying for redress. Without affecting to pass judgment on the merits of the controversy, the writer thinks this memorial well deserving of reproduction here as evidencing the devoted and pathetic attachment with which the Cherokees clung to the land of their fathers, and, remembering the wrongs and humiliations of the past, refused to be convinced that justice, prosperity, and happiness awaited them beyond the Mississippi.

The memorial of the Cherokee Nation respectfully showeth, that they approach your honorable bodies as the representatives of the people of the United States, entrusted by them under the Constitution with the exercise of their sovereign power, to ask for protection of the rights of your memorialists and redress of their grievances.

They respectfully represent that their rights, being stipulated by numerous solemn treaties, which guaranteed to them protection, and guarded as they supposed by laws enacted by Congress, they had hoped that the approach of danger would be prevented by the interposition of the power of the Executive charged with the execution of treaties and laws; and that when their rights should come in question they would be finally and authoritatively decided by the judiciary, whose decrees it would be the duty of the Executive to see carried into effect. For many years these their just hopes were not disappointed.

The public faith of the United States, solemnly pledged to them, was duly kept in form and substance. Happy under the parental guardianship of the United States, they applied themselves assiduously and successfully to learn the lessons of civilization and peace, which, in the prosecution of a humane and Christian policy, the United States caused to be taught them. Of the advances they have made under the influence of this benevolent system, they might a few years ago have been tempted to speak with pride and satisfaction and with grateful hearts to those who have been their instructors. They could have pointed with pleasure to the houses they had built, the improvements they had made, the fields they were cultivating; they could have exhibited their domestic establishments, and shown how from wandering in the forests many of them had become the heads of families, with fixed habitations, each the center of a domestic circle like that which forms the happiness of civilized man. They could have shown, too, how the arts of industry, human knowledge, and letters had been introduced amongst them, and how the highest of all the knowledge had come to bless them, teaching them to know and to worship the Christian’s God, bowing down to Him at the same seasons and in the same spirit with millions of His creatures who inhabit Christendom, and with them embracing the hopes and promises of the Gospel.

But now each of these blessings has been made to them an instrument of the keenest torture. Cupidity has fastened its eye upon their lands and their homes, and is seeking by force and by every variety of oppression and wrong to expel them from their lands and their homes and to tear them from all that has become endeared to them. Of what they have already suffered it is impossible for them to give the details, as they would make a history. Of what they are menaced with by unlawful power, every citizen of the United States who reads the public journals is aware. In this their distress they have appealed to the judiciary of the United States, where their rights have been solemnly established. They have appealed to the Executive of the United States to protect these rights according to the obligations of treaties and the injunctions of the laws. But this appeal to the Executive has been made in vain. In the hope that by yielding something of their clear rights they might succeed in obtaining security for the remainder, they have lately opened a correspondence with the Executive, offering to make a considerable cession from what had been reserved to them by solemn treaties, only upon condition that they might be protected in the part not ceded. But their earnest supplication has been unheeded, and the only answer they can get, informs them, in substance, that they must be left to their fate, or renounce the whole. What that fate is to be unhappily is too plain.

The State of Georgia has assumed jurisdiction over them, has invaded their territory, has claimed the right to dispose of their lands, and has actually proceeded to dispose of them, reserving only a small portion to individuals, and even these portions are threatened and will no doubt, soon be taken from them. Thus the nation is stripped of its territory and individuals of their property without the least color of right, and in open violation of the guarantee of treaties. At the same time the Cherokees, deprived of the protection of their own government and laws, are left without the protection of any other laws, outlawed as it were and exposed to indignities, imprisonment, persecution, and even to death, though they have committed no offense whatever, save and except that of seeking to enjoy what belongs to them, and refusing to yield it up to those who have no pretense of title to it. Of the acts of the legislature of Georgia your memorialists will endeavor to furnish copies to your honorable bodies, and of the doings of individuals they will furnish evidence if required. And your memorialists further respectfully represent that the Executive of the United States has not only refused to protect your memorialists against the wrongs they have suffered and are still suffering at the hands of unjust cupidity, but has done much more. It is but too plain that, for several years past, the power of the Executive has been exerted on the side of their oppressors and is co-operating with them in the work of destruction. Of two particulars in the conduct of the Executive your memorialists would make mention, not merely as matters of evidence but as specific subjects of complaint in addition to the more general ones already stated.

The first of these is the mode adopted to oppress and injure your memorialists under color of enrollments for emigration. Unfit persons are introduced as agents, acts are practiced by them that are unjust, unworthy, and demoralizing, and have no object but to force your memorialists to yield and abandon their rights by making their lives intolerably wretched. They forbear to go into particulars, which nevertheless they are prepared, at a proper time, to exhibit.

The other is calculated also to weaken and distress your memorialists, and is essentially unjust. Heretofore, until within the last four years, the money appropriated by Congress for annuities has been paid to the nation, by whom it was distributed and used for the benefit of the nation. And this method of payment was not only sanctioned by the usage of the Government of the United States, but was acceptable to the Cherokees. Yet, without any cause known to your memorialists, and contrary to their just expectations, the payment has been withheld for the period just mentioned, on the ground, then for the first time assumed, that the annuities were to be paid, not as hitherto, to the nation, but to the individual Cherokees, each his own small fraction, dividing the whole according to the numbers of the nation. The fact is, that for the last four years the annuities have not been paid at all.

The distribution in this new way was impracticable, if the Cherokees had been willing thus to receive it, but they were not willing; they have refused and the annuities have remained unpaid. Your memorialists forbear to advert to the motives of such conduct, leaving them to be considered and appreciated by Congress. All they will say is, that it has coincided with other measures adopted to reduce them to poverty and despair and to extort from their wretchedness a concession of their guaranteed rights. Having failed in their efforts to obtain relief elsewhere, your memorialists now appeal to Congress, and respectfully pray that your honorable bodies will look into their whole case, and that such measures may be adopted as will give them redress and security.

Source:

The Cherokee Nation of Indians is produced by Project Gutenberg and released under a public domain license.