Chapter Four: Theory, Methodologies, Methods, and Evidence

Theory Guides Inquiry

You are viewing the first edition of this textbook. A second edition is available – please visit the latest edition for updated information.

We discuss the following key subjects on this page:

Theory

Theory is an idea or model about literature in general (rather than about a specific literary work). A theory can account for

- what things are

- why they are the way they are, and

- how and why they work

Theories can be about physical things, like people or books, or abstract concepts, like patriarchy, love, or being. The English word theory derives from an Ancient Greek word theoria, meaning “a looking at, viewing, beholding.” In contrast to practical ways of knowing, theory usually refers to contemplative and reflective ways of knowing.

Theory is full of terminology and concepts that tend to grow and form recognizable shapes as we conduct research. These concepts are similar to those little sponge critters: the kind that come in capsules and expand when you leave them in water. The theory term is the compressed critter in the capsule and the fully explained concept is the expanded sponge critter. Advanced theorists and critics often use just the terminology (or the capsule, in our ‘sponge critter’ analogy) as a kind of shorthand conversation with one other. However, researchers who are unfamiliar with a theorist’s terminology have to expand their knowledge of the terminology (the capsule) by conducting additional analysis. By completing this additional analysis, researchers can come to understand each concept’s relationships to other concepts (or the expanded sponge critter, in our analogy). Once we have expanded the terminology (capsule) into the concepts (sponge critter), we can realize how valuable and significant these concepts are to our particular field of study.

Below are a few terms (and their definitions) that start with the letter “A” selected from a single book by theorist Gregory Ulmer (who borrows terms from many theoretical discourses and even invents some of his own):

- Abductive reasoning – from thing to rule.

- Abject – a formless value, not yet recognized.

- Alienation – separation from one’s capacity to act; the basis of compassion fatigue.

- Allegory – like a parable, a story with a moral linked via metaphor to another story.

- Aporia – a blind spot, an impasse, a dilemma, an inability to move ahead, or conventionally, an inability to choose between sets of equally desirable (or undesirable) alternatives.

- Apparatus – technology, institutional practices, and subject formation.

- Arabesque – an ornamental design of interlaced patterns of repeated shapes (floral or geometric) said to be the most typical feature of Islamic aesthetics.

- Aspectuality – an image whose intelligibility is determined by the aspect of the viewer; the duck-rabbit, for example.

- ATH (até) – blindness or foolishness in individual, calamity and disaster in a collective.

- Attraction and repulsion – two poles (the sublime and the excremental).

- Attunement (stimmung) – the feeling that this is how the world is; results from mapping discourses.

- Aura – a sign of recognition.[1]

We don’t expect you to learn the terms in this list; we provide them to show how dense and complicated theory can be. Notice how the definitions for each theory term above contain even more terms – like “formless,” “compassion fatigue,” and “blind spot” – that need further unpacking. Theory tends to be very dense; it crams lots of ideas into every page. Entire dictionaries are devoted to literary theory terms (see for instance Joseph Childers and Gary Hentzi. The Columbia Dictionary of Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism. Columbia University Press, 1995). There are entire dictionaries dedicated to the terms used by a single theorist (see for instance Dylan Evans. An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis. Routledge, 2006).

Literary scholars use theories to frame their perspectives of literary works. Each theory is like a different “lens” through which to view a literary work and changing lenses gives us very different views of a work. Below are a few examples of major literary theories (this list is nowhere near complete!):

Major Literary Theories

- Audience studies look at how a particular text was received in its day. Such studies might involve reading critical reviews from the period, looking at promotional materials, overall sales, and re-use of a text by other writers or artists. More recently, it could involve studying online communities and their uses and responses to a literary text.

- Cultural studies theories, such as New Historicism, Post-colonialism, or Multiculturalism, look at how texts use discourses to represent the world, social relations, and meanings. Cultural studies theories also examine the relationships of these discourses to power: how groups in power use particular discourses to justify their power and how those with less power negotiate these discourses and generate their own discourses.

- Ecological studies examine the ways that human and natural environments are represented in texts.

- Feminist studies examine the way gender and sexuality shape the production and distribution of texts, or they examine the representation of gender in texts.

- Genre studies explore what features constitute a literary genre and whether or how well a text meets these expectations, deviates from them (successfully or unsuccessfully), or establishes new genre expectations.

- Linguistic studies examine the specific uses of language within a text and can include regional dialect, novel use of terminology, the development of language over time, etc.

- Marxist studies examine the way historical and economic factors operate in the production and distribution of texts, or in the representation of social and economic relationships of people in texts.

- Post-structuralist studies make claims about instabilities within a text – particularly at how its binary structures, such as male-female, black-white, East-West, and living-dead, start to break down or take on one another’s features.

- Psychological studies look at a text, its author, or the society in which it was produced in terms of psychological features and processes. These features and processes might include identity formation, healthy or unhealthy qualities of mind, dreams and symptoms, etc.

- Queer studies challenges heteronormativity in texts and focuses on sexual identity and desire.

Before you write your research paper (or project), you should do some broad research into the theory you are assigned (or that you choose) as well as some deeper research into the specific concept(s) you will be using from that theory. Broad research can include wikipedia entries or the various “For Beginners” or “Introducing” books, such as Lacan for Beginners by Philip Hill, (1999) or Introducing Lacan by Darian Leader and Judy Groves (1995). Once you have a good general understanding of a theory, then dive into a work written by the theorist. Most literary critics combine two or more theories. They choose their theories based on their interests, their audience, or their research question. Consult with your professor or a more experienced researcher about which theory or theories to use for your research.

Each theory entails particular research questions and methods. For instance, Ecological theory, also called Ecocriticism, entails questions about the representation of human culture and nature. How or where does a text draw a line between the two? What assumptions does a text make about culture and nature? What consequences do these assumptions produce in terms of moving us towards ecological destruction or well-being? Ecological theory also entails particular research methods such as close readings of literary texts, studies of the environment, and historical research into ideas about nature and culture and how they have changed over time.

Note: in literary research, a theory is not an “unproven fact.” Rather, it is an explanation of how facts relate to one another. For instance, Marxism provides a theory of various values (such as labor value, sign value, exchange value, use value, and so on). These theories explain certain facts, like why a necklace made with diamonds and an identical-looking necklace made with costume jewels can have the same sign-value (in other words, the same power to impress) but different exchange values (one being much more expensive than another). Facts are things we can observe and the reasoned inferences we draw from those observations (i.e. that a human being is a mammal) while theories explain “the bigger picture” (like how humans evolved from other mammals).

Methodologies

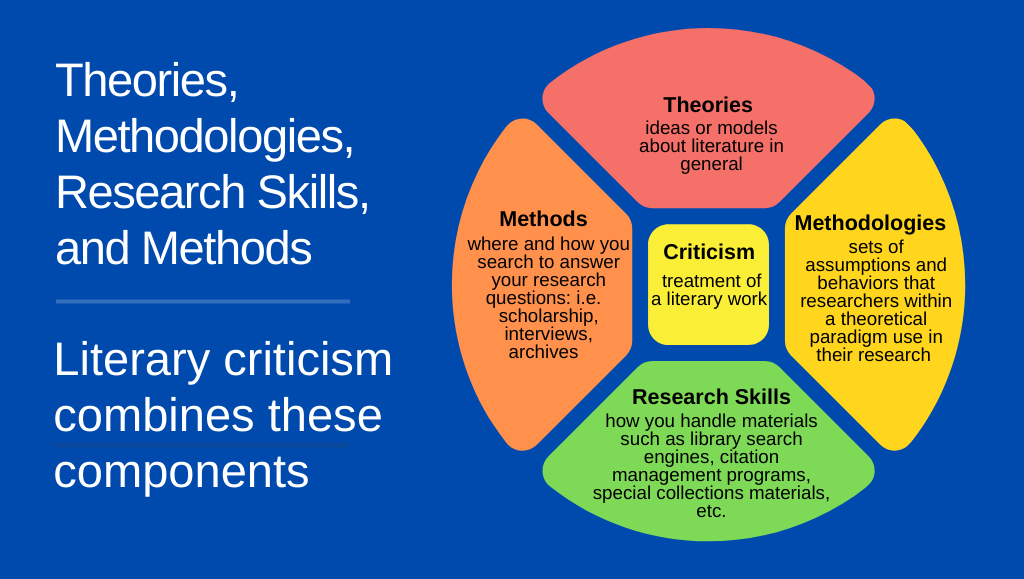

Methodologies (not to be confused with methods – more about that later) are sets of assumptions and behaviors that researchers within a theoretical paradigm use in their research.

A psychological study of a literary work will start with a set of assumptions:

- Most literary works, like a person’s unconscious, cannot speak directly to the reader but does so indirectly through images, metaphors, and intimations.

- Most literary works conceal as much as they reveal.

- Identity, whether that of a fictional character, a narrator, an author, or a reader, is a construction – an unstable linguistic effect.

The goal of a psychoanalytic reading is to describe the processes of censorship at work in a literary work and to reveal or expose the hidden unconscious of the text. To do so involves

- Seeing details of behavior and thoughts as symptoms of deeper desires and fears.

- Breaking up the “secondary revision” of the text – its apparent coherence – to deal with its fragmented and networked elements.

- Reasoning from manifest surfaces (behaviors and thoughts) to latent depths (deeper desires and fears)

- Revealing the reasoning (connecting the manifest to the latent): the ways a text uses condensation (metaphor) and displacement (metonymy), and works to both reveal and hide the latent content.

- Characterizing the text as neurotic, paranoid, perverse, etc., much as a doctor might characterize a person undergoing psychoanalysis.

Critics and theorists expand on each other’s work by extrapolating from one context to another. For instance, Freud extrapolated his most famous theory – the Oedipus Complex – from a work of literature (Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex), which he developed for use within the medical establishment to diagnose and treat patients. Critics extrapolated from Freud’s work with real people to understand the psychology of fictional characters. In your own work as a literary scholar, you can extrapolate by applying a theory to a new context. A great deal of creative or original work in the field of literary studies comes from transferring knowledge from one domain (like psychology) to another (like literature).

Criticism

Criticism is a specific treatment of a literary work. It often uses theory to make a case about the work. For example, we might start a work of literary criticism by selecting a short story by William Faulkner and considering it in terms of one of the concepts above such as abject, alienation, allegory, aporia, apparatus, aspectuality, assemblage, ATH, attraction and repulsion, attunement, or aura. Any of these ideas could make for a valuable and interesting approach to Faulkner’s work. Trying to write a paper without such concepts is unlikely to yield valuable and interesting results. Theory concepts give us lots of great material! By using the concepts and terms common to our area of study, you connect your work to the ongoing conversation, making it relevant!

Method

Method is the procedure that researchers use to answer their research question. For instance, a paper investigating Faulkner’s use of allegory may involve methods of historical research that reveal how literary authors have understood and used allegory over time. The project could also involve methods of close reading of a literary text to notice details other critics have missed. We will address both method and close reading more fully in the following pages.

- What theory or theories will you be using for your paper? Why did you make this theory selection over other theories? If you haven’t made a selection yet, which theories are you considering?

- What specific concepts from the theory/theories are you most interested in exploring in relation to the chosen literary work?

- What is your plan for researching your theory and its major concepts?

- What was the most important lesson you learned from this module? What point was confusing or difficult to understand?

Write your answers in a webcourse discussion page.

Go to the Discussion area and find the Theory Guides the Inquiry Discussion. Participate in the discussion.

Go to the Discussion area and find the Theory Guides the Inquiry Discussion. Participate in the discussion.

- Barry J. Mauer. "Introduction,”“A Glossary for Greg Ulmer's Avatar Emergency,” and “A Glossary for Greg Ulmer's Electronic Monuments." Text Shop Experiments, Volume 1. 2016 http://textshopexperiments.org/textshop01/ulmer-glossaries ↵