Phase I – Exploratory Sequential Design – Exploring, Developing, and Testing Instrument Items.

Stage 2 – Study Instrument Development and Validation

Psychometric Properties of the Cervical Smear Belief Inventory (CSBI) for Chinese Women

Su-I Hou, DrPH, CPH, MCHES, RN

Wei-Ming Luh, PhD

Abstract

This study examines the reliability and validity of the scores of Cervical Smear Belief Inventory (CSBI) among Chinese Women in Taiwan. Women who were non-adherent to cervical screening guidelines were recruited (N=424). Reliabilities showed good internal consistency for the perceived Pros, Cons, and Susceptibility scales (α ranged .78 ~ .87). Factor analysis showed good construct validity of the scores of CSBI that revealed concordant patterns with existing social and behavioral theories, except that the Norms scale was loaded with the Pros scale. Moreover, two items in the Cons scale appeared to be “cultural belief toward virginity.” Item-discrimination analysis showed that all items in the CSBI successfully discriminated women with favorable cervical smear beliefs from those with unfavorable beliefs (p<.001). In summary, many psychometric properties of the CSBI showed that the scores of the inventory were reliable and valid to assess belief towards cervical smear among Chinese women.

Keywords: Cervical Smear, Chinese Women, Construct Validity, Factor Analysis, Item Discrimination, Reliability

Note

This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by International Journal of Behavioral Medicine on 09/2005, available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1207/s15327558ijbm1203_7

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the second most common cancer among women worldwide. Although cervical cancer mortality has decreased during the past decades, recent epidemiological data from the U.S. cancer registry (Ries et al., 2000) indicates that cervical cancer disproportionately affects Asian women. Asian women have a higher incidence of cervical cancer (10.2/100,000) as compared to Caucasian women (8.4/100,000). Asian women also have a higher mortality rate of cervical cancer (2.7/100,000) than whites (2.4/100,000).

Although cervical smear tests have been proven to be an effective screening method of detecting cervical cancer at early stage, existing data suggest that Asian women do not have regular screenings. The prevalence of cervical smear among Asian women in the United States ranges from 46% to 52%, as compared to over 90% in other groups (Pham, 1992; Yi, 1994).

Among Chinese women in Taiwan, the few existing studies reported similar low rates of cervical smear test utilization, ranging from 58% to 62% (Hou, Fernandez, Bumler, Parcel, & Chen, 2003; Lee, Kuo, & Chou, 1997; Wang & Lin, 1996). In Taiwan, the National Health Insurance Plan (NHIP, 1996) provides free health care coverage of an annual cervical smear test for women age 30 years and older. Married women under 30 are also entitled to this benefit with a small co-payment. The implementation of NHIP has significantly lowered the cost barrier. Screening utilization might therefore have been improved. However, a recent study on a cervical cancer screening promotion program in Taiwan showed that 70% of the women (656/969) reported not having a cervical smear in the past 12 months (Hou, Fernandez, Baumler, & Parcel, 2002).

Chinese is the largest population subgroup in the world. The world population profile, reported by the U.S. Census Bureau (1998), estimated that the Chinese population comprised one fourth of the world’s population. It is important to understand factors influencing cervical smear utilization among this population in order to develop appropriate and effective screening promotion programs. It is also important to develop and validate a Chinese version of the screening instrument so that culturally and linguistically appropriate measurements of screening belief can be obtained.

To date, there are few published articles providing systematic efforts in developing and validating instruments used for measuring cervical smear related belief. Several studies have reported on scale development for mammography screening related belief (Champion & Scott, 1997; Champion, 1995; Rakowski, Fulton, & Feldam, 1993). Rakowski et al. (1997) tried to extend perceived pros and cons from decisional balance constructs to both mammography and cervical smear compliance. Even though some of those scale items may be modified to measure cervical smear related belief, those measures were mostly developed and tested among Western populations. It remains questionable whether they can be applied to a different cultural group such as Chinese.

Hou et al. (2003) recently developed a theory-based Cervical Smear Survey (CSS) in Chinese and pilot-tested the survey among a group of Chinese women in Taiwan (N=125). Although preliminary internal consistency of the scales in the CSS revealed an acceptable Cronbach’s alpha range (.68~.88), further revisions and validation of the instrument should be established. Verification of the psychometric properties of the scales should be done in another Chinese population before any firm conclusion can be drawn.

The purpose of this study is to examine the psychometric properties of the Cervical Smear Belief Inventory (CSBI), a modified instrument based on the previous Cervical Smear Survey (CSS) developed by Hou et al. (2003). This report describes the reliability and validity of the scores of CSBI on assessing theory-based constructs related to belief towards cervical smear among Chinese women.

Method

Study Sample

This study was conducted at one of the major teaching hospitals in Taichung, Taiwan. Women, 30 years or older (or younger if married), who had not had a cervical smear in the previous 12 months were recruited in the study. Since most screening promotion programs target at-risk women (those who are not adherent to screening guidelines) when assessing program impact, evaluation of the instrument should be tested and confirmed with a similar population. Female family members of the patients admitted to the hospital during the study period in the fall of 1999 were approached by research staff because they were considered more similar to the general community population than the female patient population. A total of 424 women participated in the study and completed the inventory.

Instrument

The original Cervical Smear Survey (CSS) was designed to represent constructs derived from existing models of health behavior (Hou et al., 2003). Major constructs included the following: (1) positive and negative evaluative beliefs regarding taking part in cervical cancer screening (constructs from the perceived Pros/Cons from the Transtheoretical Model) (Prochaska, Norcross, & DeClemente, 1994), (2) the descriptive Norms which refers to a person’s perceptions of other people’s behavior and has been found to be an important determinant of health behavior in a number of domains (Sheeran & Orbell, 1999; White, Terry & Hogg, 1994), and (3) the Susceptibility (perceived risk) from the Health Belief Model (Rosenstock, 1974). Some of the CSS items were developed and adopted from existing literatures that provided theory-based measurements; other items were developed from focus groups (N=24) conducted before the pilot study among women in Taiwan (Hou et al., 2003). The CSS instrument consisted of 11 Pros scale items (a=.88), 9 Cons scale items (a=.68), 4 descriptive Norms scale items (a=.72), and 2 Susceptibility items (a=.68).

Based on the previous analysis on the CSS and recommendations about survey revisions from Hou et al. (2003), one additional item, “Comparing with other women, my chance of getting cervical cancer is high” was added to the Susceptibility scale. Other items in the survey, especially items in the Cons scale, were re-examined and re-worded by an expert panel to improve clarity and reliability. The modified instrument was then given to a small group of Chinese women to provide feedback on item clarity, reading level, and appropriateness. Comments and additional insights from these women were used to further refine the instrument. Three more items were added into each of the Pros and the Cons scales. The final revised instrument was then named the Cervical Smear Belief Inventory (CSBI).

The four scales of the Chinese CSBI consist of 33 items: (1) perceived Pros of cervical smear (14 items); (2) perceived Cons of cervical smear (12 items); (3) descriptive Norms of cervical smear (4 items); and (4) Susceptibility (perceived risk) to cervical cancer (3 items). These scale items were developed in English, translated into Chinese, and translated back to English. Items on the two English versions were checked for discrepancy of the meaning. For each item, response was rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Data analysis

Before data were analyzed using SPSS 11.0 software, the item (Q19) “Getting a cervical smear is not an important thing for me” was reverse-coded because it is a negative expression for the Pros scale. Descriptive statistics and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were then calculated for each CSBI scale to evaluate these items and the internal consistency of scales.

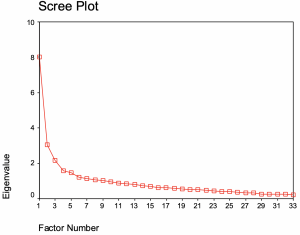

Exploratory factor analysis was used to assess the construct validity. Scree plot was used to determine the number of factors with significant eigenvalues (Cattell, 1966). Extraction method of principal axis factoring was used, along with squared multiple correlation (SMC) as the initial communality estimate. The SMCs are lower bounds of the communalities (Harman, 1976, p.149). Finally, since the relationships between theoretical constructs were assumed to be independent, varimax rotation was applied to get a clearer structure between factors.

Item-discrimination analysis was conducted to examine whether the scores of inventory discriminated women with favorable belief towards cervical smear (i.e., higher perceived Pros, lower perceived Cons, and higher Susceptibility to cancer) from women with less favorable belief. The sample was divided into two groups based on the score of each scale. Women who scored in the top one third of each scale were compared with women who scored in the bottom one third of that scale. Independent t test was used to compare item means of these two groups for each scale. It should be noted that there were no significant differences between groups on the demographic variables including age, education, and marital status, with all of the p-values greater than .05.

Result

Demographics of the Sample

Table 1 summarized the demographic characteristics of the study sample. The mean age of the women was 33.87 (SD = 8.61), and most of them were married (90%). Forty percent of the women worked full time, and 28% had a college degree or higher.

Table 1: Demographic Background of the Sample (N=424)

| Variable | N ( % ) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| <30 | 151 (35.6%) |

| 30-39 | 180 (42.5%) |

| 40-49 | 66 (15.6%) |

| >50 | 27 (6.4%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 46 (10.8%) |

| Married | 378 (89.2%) |

| Employment | |

| Full-time | 169 (39.9%) |

| Part-time | 89 (21%) |

| Housewives | 166 (39.2%) |

| Education | |

| <Elementary | 48 (11.3%) |

| Junior high | 71 (16.7%) |

| High school | 188 (44.3%) |

| >College | 117 (27.6%) |

| Prior Screening | |

| No | 176 (41.5%) |

| Yes (more than 12 months ago) | 248 (58.5%) |

| Intention of a Pap in the next year | |

| Yes | 266 (62.7%) |

| No | 158 (37.3%) |

Internal Consistency

Item mean, standard deviations, corrected item-total correlations (CITC), and “Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients if deleted” for each item were presented in Table 2. For each scale, items with discrimination (corrected item-total correlation, or CITC) less than .20 were re-evaluated for their appropriateness. The analysis showed two items (Q9 and Q22) had low CITC (<.20): “My partner / husband would not want me to have a cervical smear” (Q9), and “I would feel more comfortable to obtain a cervical smear if a female doctor performs the procedure” (Q22). These two items also showed low item-total correlation with other items in the correlation matrix (data not shown). Moreover, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient increased from .78 to .81 after removing these two items from the Cons scale. Internal reliabilities (Cronbach’s alpha) for the perceived Pros, Cons, Norms, and Susceptibility scales were .87, .81, .63 and .80 respectively.

Descriptive Statistics of the Scales

Among all the scales, the perceived Pros (14 items) had the largest scale mean (58.22) and the smallest standard deviation (5.68). The data indicated that women’s belief related to perceive Pros was not only very positive but also homogeneous among these women. However, the overall perceived barriers to a cervical smear were somewhat medium in the Cons scale (scale mean=27.65, SD=6.16, 10 items). Data of the Cons scale showed higher variations than the Pros scale among Chinese women who had not had a cervical smear in the past 12 months. The scale mean (SD) for descriptive Norms (4 items) and Susceptibility (3 items) were 15.69 (1.95) and 8.49 (2.11), respectively.

Table 2: Item means, standard deviations, corrected item-total correlation (CITC), and alpha coefficients if item deleted for each CSBI scale (N=424)

| Item | Item Description | Mean (SD) | CITC | Alpha if item deleted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pros | ||||

| Q2 | A cervical smear can find a problem before it develops into cancer. | 4.00 (0.70) | 0.34 | 0.87 |

| Q4 | A cervical smear can find cancer at a point when it is likely to be cured. | 4.02 (0.70) | 0.31 | 0.87 |

| Q6 | The cervical smear procedure is very simple and quick. | 4.04 (0.68) | 0.50 | 0.86 |

| Q7 | Regular cervical smear test gives me peace of mind about my health. | 4.21 (0.62) | 0.59 | 0.86 |

| Q8 | Having a cervical smear every year gives me a feeling of control over my health. | 4.21 (0.60) | 0.63 | 0.86 |

| Q10 | My family will think that I take care of myself if I have annual cervical smears. | 4.14 (0.68) | 0.61 | 0.86 |

| Q11 | My partner/husband will support me if I want to have a cervical smear. | 4.29 (0.73) | 0.51 | 0.86 |

| Q12 | I am willing to obtain a cervical smear for health reason. | 4.27 (0.59) | 0.67 | 0.85 |

| Q13 | I can encourage my friends to have a cervical smear if I do it myself. | 4.22 (0.61) | 0.64 | 0.85 |

| Q14 | I feel having annual cervical smear is a way to show I take care of my family. | 4.21 (0.67) | 0.63 | 0.85 |

| Q15 | I want to have a cervical smear because I need to take care of my family. | 4.17 (0.70) | 0.54 | 0.86 |

| Q16 | Cervical cancer in the early stage has high chance to be cured. | 4.11 (0.72) | 0.42 | 0.87 |

| Q19r | Getting a cervical smear is not an important thing for me (reverse coded). | 4.03 (0.76) | 0.47 | 0.86 |

| Q21 | The early a cervical cancer is detected, the higher chance of a cure. | 4.31 (0.54) | 0.64 | 0.86 |

| Cons | ||||

| Q1 | I feel cervical cancer smear hurts. | 2.48 (0.90) | 0.37 | 0.76 |

| Q3 | I feel embarrassed to have a cervical smear. | 2.82 (1.13) | 0.55 | 0.74 |

| Q5 | A cervical smear test makes me nervous. | 3.24 (1.08) | 0.51 | 0.75 |

| Q9 | My partner/husband would not want me to have a cervical smear. | 2.48 (1.41) | 0.17* | 0.80 |

| Q17 | I do not have time for a cervical smear test. | 2.41 (0.93) | 0.43 | 0.76 |

| Q18 | It is too much trouble for me to obtain a cervical smear test. | 2.31 (0.84) | 0.61 | 0.74 |

| Q20 | I feel uncomfortable if a male doctor exam me. | 3.06 (1.12) | 0.50 | 0.75 |

| Q22 | I feel more comfortable to have a smear if a female doctor performs the procedure. | 4.06 (0.85) | 0.07* | 0.79 |

| Q23 | I would only have cervical smears if I got reminders from my doctor. | 2.70 (0.98) | 0.59 | 0.74 |

| Q24 | I would not have a smear unless I had some vagina symptoms or discomfort. | 2.57 (0.99) | 0.58 | 0.74 |

| Q25 | I will not have a cervical smear if I am not sexually active. | 3.06 (1.04) | 0.33 | 0.77 |

| Q26 | I will not have a cervical smear if I am not married. | 3.03 (1.03) | 0.36 | 0.76 |

| Norm | ||||

| Q27 | Cervical smear is now a very routine medical test. | 4.08 (0.62) | 0.31 | 0.62 |

| Q29 | Other women in my age obtain a cervical smear regularly. | 3.58 (0.82) | 0.40 | 0.56 |

| Q30 | All women should have regular cervical smears. | 4.25 (0.59) | 0.48 | 0.51 |

| Q32 | People I know think cervical smear is very important. | 3.78 (0.79) | 0.46 | 0.51 |

| Risk | ||||

| Q28 | I feel my chance of getting cervical cancer is high. | 2.72 (0.81) | 0.62 | 0.76 |

| Q21 | I might get cervical cancer at some point during my life. | 3.06 (0.89) | 0.60 | 0.79 |

| Q33 | Comparing with other women, my chance of getting cervical cancer is high. | 2.71 (0.78) | 0.74 | 0.64 |

Construct Validity

After the internal consistency analysis, the data, without Q9 and Q22, were subjected to exploratory factor analysis. An examination of the Scree plot (Figure 1) for the eigenvalues of the correlation matrix, together with an inspection of the coefficients of the first four components, showed a four-factor solution. The first few eigenvalues dropped precipitously, and after the fourth, a gradual linear decline set in. Four factors extracted by the principle axis factoring method were then obtained. The resulting factor structure (not shown) indicated that the items corresponded very closely with the intended scales. All the factor loadings associated with the theoretical constructs were greater than .3, which were considered meaningful to the factor (Nunnally, 1994). The only discrepancy between the observed data and intended construct was revealed among four items (Q27, Q29, Q30, Q32). These four items, which were supposed to measure descriptive Norms, were all collapsed with Factor I.

The result with a clearer structure was obtained using Varimax rotation (Table 3). The variances explained after rotation for Factor I to IV were 19%, 10%, 6% and 5%, respectively. Factor I was relatively a dominant factor to the other three factors. The 14 items in the perceived Pros scale were clustered as Factor I, along with Q27, Q29, Q30, and Q32. Eight out of ten items in the perceived Cons scale were clustered as Factor II. The four items of the Susceptibility scale were clustered as Factor III. Finally, Q25 and Q26, which were supposed to belong to the Cons scale, formed Factor IV. Based on the intended theoretical constructs designed in the inventory, Factor I was named as “perceived Pros”, Factor II “perceived Cons”, and Factor III “Susceptibility.” These three factors consisted of the intended structure of respective scales. It should be noted that Q25 (“I will not have a cervical smear if I am not sexually active”) and Q26 (“I will not have a cervical smear if I am not married”) were developed based on data from the focus group interview in the pilot study. Results showed that these two items were independent from other items. This was possibly due to the cultural value towards virginity among the Chinese female population. Therefore, the two items, loaded in Factor IV, were labeled as “cultural belief towards virginity.”

It should also be noted that the results obtained after the Varimax rotation showed some items were loaded on both Factor I and Factor II (Q12, Q17, Q18, and Q24). Data showed if these items were loaded to Factor I with positive values, it would also have a negative loading on Factor II, and vice versa. Women who agreed highly on Q12 (“willing to obtain a cervical smear for health reasons”) may also perceive less barriers of obtaining a screening. On the other hand, those who perceive no time (Q17) or too much trouble of getting a cervical smear (Q18) may perceive less benefits of a screening. In addition, if women experienced vaginal discomfort (Q24), they tended to perceive more benefit of getting a cervical smear.

Table 3. Rotated Factor Structure for the CSBI scale items (N=424)

| Scale | Item # | Factor I | Factor II | Factor III | Factor IV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pros | Q2 | 0.37 | |||

| Q4 | 0.36 | ||||

| Q6 | 0.52 | ||||

| Q7 | 0.60 | ||||

| Q8 | 0.66 | ||||

| Q10 | 0.67 | ||||

| Q11 | 0.51 | ||||

| Q12 | 0.67 | -0.31 | |||

| Q13 | 0.67 | ||||

| Q14 | 0.67 | ||||

| Q15 | 0.58 | ||||

| Q16 | 0.44 | ||||

| Q19r | 0.48 | ||||

| Q21 | 0.67 | ||||

| Norms | Q27 | 0.43 | |||

| Q29 | 0.37 | ||||

| Q30 | 0.67 | ||||

| Q32 | 0.38 | ||||

| Cons | Q1 | 0.46 | |||

| Q3 | 0.67 | ||||

| Q5 | 0.66 | ||||

| Q17 | -0.38 | 0.41 | |||

| Q18 | -0.41 | 0.63 | |||

| Q20 | 0.62 | ||||

| Q23 | 0.51 | ||||

| Q24 | -0.30 | 0.47 | |||

| (Cultural belief) | Q25 | 0.76 | |||

| Q26 | 0.82 | ||||

| Susceptibility | Q28 | 0.72 | |||

| Q31 | 0.68 | ||||

| Q33 | 0.88 | ||||

| Eigenvalues | 6.03 | 3.18 | 1.83 | 1.6 | |

| Variance explained (%) | 19.44% | 10.26% | 5.9% | 5.2% |

Discriminate Validity

Item-discrimination analysis was examined by comparing item means between women who scored in the top one third and those who scored in the bottom one third in each scale. Table 4 shows that all of the items in the Pros, Cons, and Susceptibility scales had significant discriminate validity (p<.001), which indicated that the CSBI successfully discriminated women with favorable belief towards cervical smear from those with less favorable belief. A previous pilot study using CSS found that women reporting previous cervical smear(s) scored higher on perceived Pros, lower on perceived Cons, as well as higher on perceived Norms about cervical smear than women who reported never had a cervical smear. Therefore, previous study results had provided good indications that the instrument discriminated those who have had a screen from those who have not.

Table 4: Item-discrimination analysis between women who scored in the top one third (high) and those in the bottom one third (low) of each scale (Pros, Cons, and Susceptibility)

| Pros Scale | |||||

| Item | High Pros group (n=158) (scale mean >60) |

Low Pros group (n=130) (scale mean <55) |

t score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item Mean | Item SD | Item Mean | Item SD | ||

| Q2 | 4.56 | 0.72 | 3.62 | 0.67 | -7.35* |

| Q4 | 4.27 | 0.82 | 3.65 | 0.62 | -7.29* |

| Q6 | 4.46 | 0.61 | 3.67 | 0.69 | -10.26* |

| Q7 | 4.63 | 0.55 | 3.76 | 0.51 | -13.98* |

| Q8 | 4.67 | 0.51 | 3.79 | 0.57 | -13.83* |

| Q10 | 4.62 | 0.58 | 3.67 | 0.66 | -12.95* |

| Q11 | 4.81 | 0.68 | 3.76 | 0.54 | -14.29* |

| Q12 | 4.78 | 0.43 | 3.85 | 0.45 | -17.73* |

| Q13 | 4.66 | 0.54 | 3.79 | 0.55 | -13.54* |

| Q14 | 4.71 | 0.48 | 3.72 | 0.66 | -14.76* |

| Q15 | 4.63 | 0.69 | 3.71 | 0.64 | -11.70* |

| Q16 | 4.54 | 0.73 | 3.68 | 0.60 | -11.09* |

| Q19r | 4.47 | 0.59 | 3.54 | 0.81 | -10.92* |

| Q21 | 4.76 | 0.44 | 3.95 | 0.38 | -16.76* |

| Cons Scale | |||||

| Item | Low Cons group (n=138) (scale mean <24) |

High Cons group (n=158) (scale mean >30) |

t score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item Mean | Item SD | Item Mean | Item SD | ||

| Q1 | 1.93 | 0.73 | 2.92 | 0.86 | -10.63* |

| Q3 | 1.92 | 0.67 | 3.61 | 0.94 | -18.03* |

| Q5 | 2.36 | 0.95 | 3.92 | 0.73 | -15.69* |

| Q17 | 1.86 | 0.67 | 3.00 | 0.93 | -12.17* |

| Q18 | 1.75 | 0.50 | 2.92 | 0.92 | -13.91* |

| Q20 | 2.31 | 0.89 | 3.79 | 0.88 | -14.30* |

| Q23 | 1.98 | 0.66 | 3.43 | 0.83 | -16.77* |

| Q24 | 1.88 | 0.69 | 3.32 | 0.85 | -16.20* |

| Q25 | 2.46 | 0.97 | 3.54 | 0.89 | -10.03* |

| Q26 | 2.41 | 0.99 | 3.54 | 0.84 | -10.65* |

| Susceptibility Scale | |||||

| Item | High Susceptibility (n=100) (scale mean >10) |

Low Susceptibility (n=154) (scale mean <8) |

t score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item Mean | Item SD | Item Mean | Item SD | ||

| Q28 | 3.49 | 0.63 | 1.97 | 0.70 | -18.05* |

| Q3 | 4.01 | 0.56 | 2.40 | 0.93 | -17.16* |

| Q5 | 3.40 | 0.65 | 1.98 | 0.67 | -16.66* |

Discussion

This study showed that the scores of CSBI had good internal consistency for the Pros (α=0.87), Cons (α=0.81), and Susceptibility (α=0.80) scales, and reasonable internal consistency for the Norm scale (a=0.63).

To obtain a valid assessment, two items (Q9, Q22) with low CITC were not included in the construct validity assessment. Exploratory factor analysis for the remaining 31 items showed that the factor structure of the CSBI items was loaded in a way highly consistent with the intended conceptual theory constructs. Factors I, II, and III corresponded to perceived Pros, Cons, and Susceptibility constructs, respectively. The four items in the Norm scale, however, were collapsed into the Pros scale. Furthermore, Q25 and Q26 were clustered as Factor IV, which was then labeled as “cultural beliefs toward virginity.”

Regarding the perceived Cons scale in the CSBI, the current study suggested Q9 and Q22, which had low CITC, might need to be revisited in the future. Q22 (preference of female doctor) seems to be the most significant Cons (barrier) that every woman endorsed (mean=4.06, SD=0.85), and Q9 (“My partner / husband would not want me to have a cervical smear”) showed greatest variation (mean=2.48, SD=1.41). One possible explanation could be that Q9 measured more of subjective norms of screening (i.e., what women think others think they should do) rather than perceived Cons of screening. Nevertheless, the researchers suspected that barriers were more complex. In Chinese culture, husband is the head of the family and decision maker. If the husband does not encourage or even ignore the importance of having a cervical smear, the wife just won’t do it (Hibbard & Pope, 1987). Thus, future intervention needs to put more efforts on developing effective intervention messages and strategies that address or reduce women’s concerns.

Two items, Q25 (“I will not have a cervical smear if I am not sexually active”) and Q26 (“I will not have a cervical smear if I am not married”) were originally considered part of the Cons scale; however, they were loaded into Factor IV (cultural belief towards virginity). Beliefs about virginity among the female Chinese population could be a cultural issue instead of regular health concerns. Other research also showed that shyness or shamefulness is another barrier women have regards having a smear (Yi, 1998). Therefore, the current study suggested that this factor should be formed as an independent scale to assess the uniqueness of cultural and social influence on women’s screening behavior. Some previous studies also indicated values about virginity might be associated with cervical smear behavior among young Asian women (Hou & Lessick, 2002; Yi, 1998). Since a reliable measure of a construct (Nunnally & Bernstein 1994) should consist of at least 3 items, additional items should be developed in the future to make this factor into a reliable scale.

The study showed that the Norms scale did not cluster as a separate factor. They were, however, loaded with the Pros scale. We suspect that in Chinese culture, people tend to conform to societal norms. Statements related to descriptive norms that describe beliefs about the behavior of the population as a whole, such as beliefs of cervical smear as a routine medical screening or other women like her receive a cervical smear (descriptive Norms), might appear to many Chinese women as an assessment of screening benefits (perceived Pros). Further research should investigate this construct among the Chinese population before any firm conclusion can be made.

In summary, consistent with the theoretical constructs, findings from this study indicated that the scores of the CSBI were reliable and valid for assessing psychosocial beliefs towards cervical smear among Chinese women. The current findings of the CSBI also shed light on the screening issues with respect to Chinese cultural beliefs. Public health programs that aim to address health disparity issues among different ethnic groups should understand how cultural values and beliefs influence the screening practice, and therefore, develop programs using culturally appropriate messages and strategies. This study not only demonstrated the success of developing a theory- and evidence-based tool to assess cervical smear beliefs among Chinese women, but also showed reliable and valid results on the scores of Cervical Smear Belief Inventory (CSBI). In addition, its culturally sensitive measurements on belief towards cervical smear test can greatly raise awareness of specific public health concerns and enhance future program evaluations conducted for similar populations.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Cheng-Ching Hospital in Taichung, Taiwan. Special thanks to Pai-Ho Chen, director of the Department of Nursing who assisted with the coordination of the program. This research was approved by The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects (CPHS) at The University of Texas – Houston Health Science Center, School of Public Health (HSC-SPH-99-013).

References

Cattell, R. B. (1966). The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 1, 245-276.

Champion, V.L. (1995). Development of a benefit and barriers scale for mammography utilization. Cancer Nursing, 18 (1), 53-59.

Champion, V.L. & Scott, C.R. (1997). Reliability and validity of breast cancer screening belief scales in African American women. Nursing Research, 46, 331-337.

Harman, H. H. (1976), Modern factor analysis. The University of Chicago Press.

Health and Vital Statistics. (1998) Department of Health, the Executive Yuan, Republic of China.

Hibbard, J.H. & Pope, C.R. (1987). Women’s role, interest in health behavior. Women & Health, 12, 67-84.

Hou, S., Fernandez, M., Baumler, E., Parcel, G & Chen, P. (2003). Correlates of cervical cancer screening among women in Taiwan. Health Care for Women International, 24(5), 384-398.

Hou, S., Fernandez, M., Baumler, E., & Parcel, G. (2002). Effectiveness of an intervention to increase Pap test screening among Chinese women in Taiwan. Journal of Community Health, 27(4), 277-290.

Hou, S.& Lessick, M. (2002). Cervical cancer screening among Chinese women: Exploring the benefits and barriers of providing care. AWHONN Lifelines, 6(4), 349-354.

Lee, T.F., Kuo, H.S., & Chou, B.S. et al. (1997). Factors of Pap screening behavior among women in King-Men, Taiwan. Public Health of Republic of China.16 (3),198-209.

Nunnally, J.C & Bernstein, I.H. (1994). Psychometric Theory. (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc.

Pham, C.T. & McPhee, S.J. (1992). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of breast and cervical cancer screening among Vietnamese women. Journal of Cancer Education, 7(4), 305-310.

Prochaska,J.O., Norcross, J.C. & DiClemente, C.C. (1994). Changing for good. (3rd ed.). New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc.

Rakowski, W., Fulton, J.P. & Feldam, J.P. (1993) Women’s decision making about mammography: A replication of the relationship between stages of adoption and decisional balance. Health Psychology. 12(3), 209-214.

Rakowski, W., Clark, M.A., Pearlman, D.N., Ehrich, B., Rimer, B.K., Goldstein, M.G., Dube, C.E. & Woolverton, H. III. (1997) Integrating pros and cons for mammography and pap testing: Extending the construct of decisional balance to two behaviors. Preventive Medicine.26, 664-673.

Ries, L.A., Wingo, P.A., Miller, D.S., et al. (2000). The annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973 – 1997, with a special section on colorectal cancer.Cancer, 88(10),2398-2424.

Rosenstock, I.M. & Krischt, J.P. (1974). The Health Belief Model and personal health behavior. Health Education Monographs, 2, 470-473.

Sheeran, P. & Orbell, S. (1999). Augmenting the theory of planned behavior: Roles for anticipated regret and descriptive norms. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29, 2107-2142.

US Census Bureau. (1998). World population profiles:1998. Retrieved May 26, 2002 on the World Wide Web: http://www.census.gov/ipc/prod/wp98/wp98.pdf

Wang, P.D. & Lin, R.S. (1996). Socio-demographic factors of Pap smear screening in Taiwan. Public Health, 110(2), 123-127.

White, K.M., Terry, D.J. & Hogg, M.A. (1994). Safer sex behavior: The role of attitudes, norms and control factors. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24,2164-2192.

Yi, J.K. (1994). Factors associated with cervical cancer screening behavior among Vietnamese women. Journal of Community Health, 19(3), 189-200.

Yi, J.K. (1998). Acculturation and Pap screening practices among college-aged Vietnamese women in the United States. Cancer Nursing, 21(5),335-341.

Feedback/Errata