5

Practicing Archaeology

Learning Objectives:

- Explain what we can learn about the past from archaeological evidence

- Discuss the basic techniques of archaeological excavation

- Summarize different theoretical approaches and challenges to interpreting the past

- Assess how archaeological discoveries and interpretations are used in validating modern ideologies

The Record of the Past

Archaeology is the sub-discipline of anthropology that studies culture using material remains. These remains are often called material culture because they are physical manifestations of cultural behaviors and knowledge. Material culture comes in many forms including art, architecture, artifacts (pottery, stone tools, textiles, jewelry, etc.), human bones, animal bones and shell, ecological remains, and modifications to the landscape. Anything that a culture created or modified is part of the archaeological record.

Material Culture

Remember that culture is the learned and shared beliefs and behaviors of a group of people. While we cannot excavate culture directly, culture influences the physical remains ( material culture ) that archaeologists find. There are many kinds of material culture and they range from large immovable objects (like buildings or monuments), to smaller portable objects ( artifacts, Figure 5.1), to collections of material culture and the remains of human behavior that only make sense in association with another and cannot be moved. This is called a feature and includes burials, pieces of architectures (Figure 5.2), postholes, fire pits, or trash middens.

Figure 5.1: This polychrome painted ceramic bowl is an example of a Maya artifact

Figure 5.2: Archaeologists excavated this exterior wall, an archaeological feature uncovered at an ancient Maya site

Figure 5.3: Pollen grains are microscopic examples of organic ecofacts

Material culture also includes ecofacts or remains of ecologically related objects that humans did not craft into artifacts, but were consumed, used to make other forms of material culture, or contain traces of activity. Ecofacts can be organic (things that used to be alive) or inorganic (something that was never alive like rock or soil). Organic ecofacts include things like animal bone, shell, pollen (Figure 5.3), seeds, and carbon, while inorganic ecofacts include things like minerals (Figure 5.4), soil deposits, or plaster.

Figure 5.4: Minerals like the ones displayed here were frequently used by people in the past for a variety of purposes and are excellent examples of inorganic ecofacts

Figure 5.5: Many archaeologists focus on the relationship between past peoples and their environments, then apply what they learn to current environmental issues

Archaeologists use material culture to understand and reconstruct the behaviors and knowledge of people living in the past. Archaeology not only helps us to appreciate and preserve past culture, it also informs major issues or current problems that we are facing (Figure 5.5). For example, how did ancient populations respond to sudden changes in climate? Did they have behaviors and technologies we can utilize in our current climate crisis? How did rulers of archaic states use ideology to maintain social control and institutionalize inequalities? Were certain populations able to break free from this ideology to create a more equitable society? It’s always important to remember that archaeology’s analytical power resides not only in the past, but also its application to present and future problems.

Kinds of Archaeology

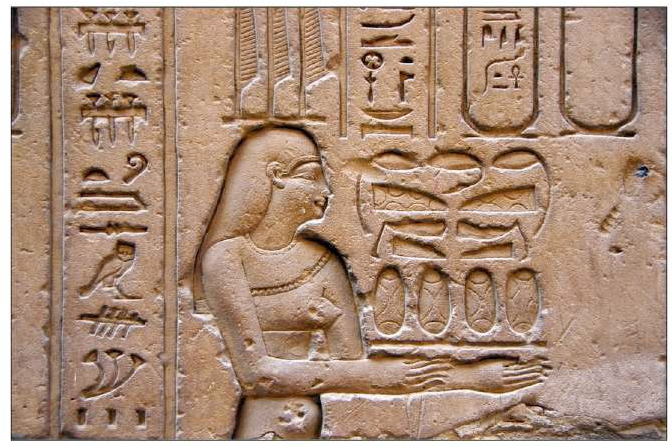

There are many kinds of archaeology and archaeologists. Prehistoric archaeologists study time periods before the invention of writing and might study topics like the peopling of the New World during the late Pleistocene. Historical archaeologists study time periods and cultures that produced written documents. They use these written documents, along with material culture, to interpret behaviors and life in the past. There are many historical archaeologists working in the U.S. today on various cultures and events from the revolutionary war to the industrial revolution to ethnic migrations. Archaeologists usually focus on a particular culture that is associated with a chronological period and area: for example, Classical archaeology covers the civilizations affected by the Greeks and Romans, Egyptology exclusively investigates Egypt (Figure 5.6), and Mesoamerican archaeology focuses on cultures in modern day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador.

Ethnoarchaeologists combine cultural anthropology and archaeology to study contemporary people in an effort to document how people make, use, and dispose of the objects they use today. Ethnoarchaeologists use this information to inform the study of past peoples living in the same are or living a similar lifeway in a different area. Environmental archaeologists help us understand the relationship between past peoples and their natural environment including their management of resources and response to natural disasters. Experimental archaeologists often work with or are ethnoarchaeologists. They work to reconstruct techniques and processes used in the past to create artifacts, art, and architecture that we see in the archaeological record.

Figure 5.6: Egyptologists exclusively study the cultures of Egypt

Figure 5.7: Underwater archaeology using a unique set of methods to investigate material culture submersed in oceans, lakes, and rivers

Underwater archaeologists exclusively study material culture that is now underwater. This includes features like shipwrecks and sites now submerged by rising sea levels (Figure 5.7). As we mentioned earlier, Cultural Resource Managers (CRMs) are applied anthropologists who use method and theory from archaeology to manage, protect, and preserve cultural resources in the private sector.

Archaeological Research

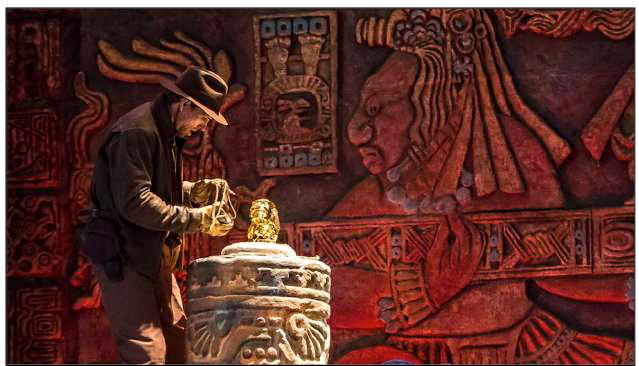

Despite how archaeologists are portrayed in popular media – searching for treasure to gain wealth or prestige, or hunting down artifacts to put in a museum (Figure 5.8) – all legitimate scientific archaeology begins with a research question. Questions are limitless and can range from the empirical (e.g., how did a group of people respond to a documented historical event?) to the theoretical (e.g., where does social inequality come from?).

After formulating a research question and applying it to a specific culture in the past, a team of archaeologists will create a number of hypotheses in order to answer their question about behavior in the past. They will build a research design that incorporates relevant archaeological and social theory about human behavior, past work from previous scholars who have worked on similar questions, a sampling strategy for

Figure 5.8: Despite popular depictions, archaeologists are not treasure seeking adventurers, but scientists trying to understand the way humans lived in the past

Figure 5.9: Large-scale excavations like this one in Egypt take years to plan, a great deal of money to fund, and require close collaboration with local governments and communities

excavation, methods for excavation and analysis of what they find, a list of limitations for their study, reasonable expectations, a detailed budget, schedule, and possible outlets for publication and dissemination of their findings (Figure 5.9).

The team will then seek funding for their research from a private agency like a university or research foundation (for example, the National Geographic Society) or even a government agency (like the National Science Foundation). If they are awarded funding, the long process of being granted permission to carry out research begins. All archaeologists must gain permission to excavate and carry out analysis from some entity or another. Usually this involves the government of a country, but it can also involve getting permission from local indigenous groups who are descendants of the people that are being studied. Only after this long and critical process involving research design, funding, and permission has been completed can the team of research archaeologists start their investigation.

Locating and mapping sites

Archaeologists often know where sites are located and formulate a specific research design to excavate a certain area. Evidence for sites can include previous research reports, explorer’s logs, old maps, historical data, satellite photos, anecdotal stories from community members, or even cultural myths and stories. Once archaeologists identify a site they begin a surface survey or walking exploration of the area (Figure 5.10). Surface surveys can be formal or informal. An informal survey may include a few archaeologists simply walking through a potential site and noting architectural features or artifact scatters they can see with their eyes. A formal survey may involve a team of archaeologists walking at certain intervals apart from another who document, map, and collect any features or artifacts they see on the surface.

After survey, mapping begins. Mappers can be archaeologists trained specifically in survey and mapping techniques, or they can be general archaeologists who also have mapping skills. Depending on time and resources, mappers may use a simple measuring tape and compass to create a two-dimensional map of a site. They could use an older instrument called a theodolite (a surveying instrument with a rotating telescope for

Figure 5.10: Archaeological investigation can begin with a simple walking survey

measuring horizontal and vertical angles). Or mappers could use an Electronic Distance Measuring tool (EDM) like a Total Station (Figure 5.11). This kind of instrument usually requires at least two people – one to work the machine and one to hold a prism attached to a stadia rod at certain points on the landscape. The machine operator tells the person with the prism where to stand and then uses the machine to shoot a laser at the prism. The light reflects back to a sensor and the machine computes the horizontal and vertical location of the point in relation to the machine. In this way, three-dimensional maps of a site composed of thousands of individual points can be created. These maps are precise to within centimeters and can later be related to absolute mapping coordinates using Geographical Information System (GIS) program. Mappers can then manipulate these GIS maps using software to learn a great deal about a site – for example, how water flowed through the site, if certain buildings could be viewed from other buildings, or even how the site was related to astronomical or celestial bodies.

Figure 5.11: An archaeologist trains a graduate student on how to use a Total Station, a kind of Electronic Distance Measuring device (EDM)

Mappers can also using Global Positioning System (GPS) units to map a site when they cannot carry a Total Station. GPS units are small portable mapping computers that are linked to satellites that can tell you where you are on a landscape. They work best in open areas not covered by trees.

More recently, archaeologists have been using imagery generated by satellites, space shuttles, airplanes, and drones (Figure 5.12) to identify sites and features. On the ground, archaeologists have also been employing geophysical prospecting tools like magnetometers, conductivity meters, and ground-penetrating radar (GPR), to help them identify subsurface features like building foundations or open spaces that indicate burials. These are all examples of remote sensing techniques that archaeologists can use to find archaeological features without penetrating the ground.

Figure 5.12: Drones mounted with cameras have fast become an economical and efficient means of remote sensing for archaeologists

Excavation methods and tools

Excavation involves systematically uncovering, documenting, and collecting evidence of cultural behavior at a site. After a site has been abandoned, soil and other natural debris steadily accumulate over architecture and culturally constructed surfaces like plazas. This build-up can be more dramatic if the site was abandoned or destroyed due to a severe climatic event. When sites are occupied as they grow, become modified, are destroyed, and reconstructed, successive layers of debris develop above and around artifacts and features. These layers are called strata, and the recording and “reading” of the layers is called stratigraphy (Figures 5.13 and 5.14). Archaeology and some earth sciences like Geology specialize in the study of examining these changing layers.

Figure 5.13: This Guatemalan archaeologist prepares to draw the profile of his excavation noting the depths, texture, and color of different layers of stratigraphy

Figure 5.14: Changes in stratigraphy can be subtle when you excavate, but they become clearer in the profile of excavation units like the ones here

However, archaeologists are mostly concerned with studying strata created by human behavior. Archaeology and Geology also share the application of the Law of Superposition or general principle that older remains are found on the bottom of stratigraphic columns while newer or more recent remains appear at the top.

Archaeologists evaluate and record an archaeological site in order to preserve the context of artifacts and features, and they work in teams with many other specialists. Site maps are divided into units – usually grid-squares of specific dimensions (like 100m by 100m). This is done to sample and excavate the site in a systematic way. Where and why archaeologists decide to excavate at a site is called a sampling strategy (Figure 5.15) and is an integral component of all archaeological research. No team of archaeologists has enough funding and time to excavate everything at a site –nor would they want to. Because excavation is a partially destructive process, they only want to excavate what they need to, and leave areas unexcavated so that others can examine the site again in the future.

The mapper will establish a central datum point, or an easily identifiable, fixed spot at a known elevation above sea level. Each excavator will record the vertical horizontal relationships of each pit they excavate in relation to the datum point (Figure 5.16). Within each grid- square on the map, archaeologists will place their excavations where

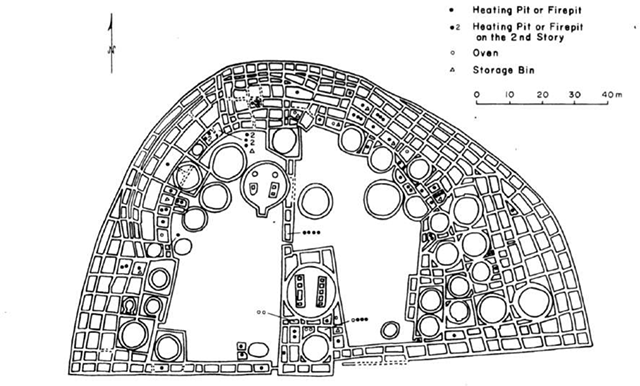

Figure 5.15: Archaeologists did not have the time, resources, or permission to dig all of a compound at the famous Native American site of Pueblo Bonito, so they created a sampling strategy to excavate the rooms they thought would produce an accurate representation of life in the past

Figure 5.16: This archaeologist measures the depth of stratigraphy layers in her excavation from a local datum point that is related to a central datum point at the site

they deem appropriate. Excavation units can be geometrical (e.g., a 1 x 1m square) or they can follow the contours and shape of a feature. A datum point is also created on the corner of each excavation and related to the central datum point at the site. In this way, every archaeologist can compare the stratigraphy in their pits to one another, because they are linked to the fixed elevation point of the central datum. Archaeologists excavate down in arbitrary levels (e.g., 20 cm strata) or they follow the depth of the cultural deposits uncovered. When a new cultural level is unearthed (or when the arbitrary depth is reached), the level is closed and a new one is begun. All the artifacts found in one level are collected and labeled according to artifact class, level, and perhaps even horizontal location in the pit.

Common tools that archaeologists use include shovels and pick-axes for intensive excavation, mason trowels to loosen dirt around smaller finds, and fine instruments like wooden skewers, dental tools, small brooms, and brushes to excavate delicate remains (Figure 5.17). For large-scale projects that require the removal of deep or dense layers of modern debris, archaeologists may use bulldozers and backhoes – but this is only to remove topsoil and overgrowth. The primary tool used by most archaeologists is the triangular or rectangular mason’s trowel, which they use to scrape away the soil in horizontal motions. As we explain below, archaeologists are most interested in determining the contexts (settings/associations/relationships) between artifacts and features, so they prefer to expose cultural layers of deposition horizontally, not vertically, until all the finds in an area have been exposed and their relationships noted.

Figure 5.17: Some of the archaeologist’s most trusted tools – a masonry trowel, small pick, brush and a metal dustpan

Analysis of materials

Before removing any artifact, an archaeologist carefully records its position in the excavation unit through written documentation, drawings, photography, and measurement in relation to the local and central datum point. Like geologists, archaeologists are trained to notice changes in soil texture, color, and density, and to note and draw these changes. Soil from each cultural layer is usually sifted through a screen in order to catch smaller pieces of cultural material that may not be distinguishable in the excavation unit. Soil may also be saved for a process called flotation, in which an archaeologist places dried soil on a screen of mesh wire cloth (Figure 5.18).

Figure 5.18: Archaeologists create an ad hoc flotation device to find small pieces of organic and inorganic material

Figure 5.19: The archaeological context where these ceramic vessels were found is an ancient Maya midden

Water is gently bubbled up through the cloth and soil. Less dense materials like seeds and charcoal “float” to the surface of the water while tiny pieces of heavier material like stone micro-debitage and bone fragments remain on the mesh.

After excavation, artifacts and other finds are transported to a safe and secure laboratory facility where they will undergo analysis for many months. When archaeologists analyze an artifact they methodically examine it in relation to one of four contexts. We like to think of there being four kinds of contexts in archaeology. A context is essentially the setting or circumstances in which artifacts are found.

Archaeological context refers to the immediate association of artifacts and features found within an area or layer, and the relationship of this area or layer to what lies above and below it (Figure 5.19). Was an artifact found in a burial? Trash midden? Construction fill? These are all examples of archaeological contexts.

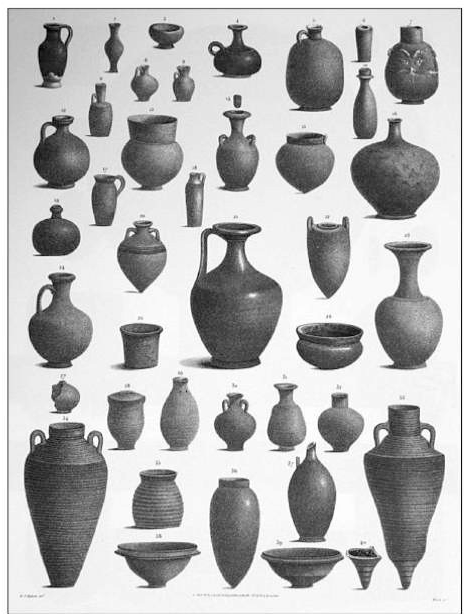

Chronological context refers to the time period in which the artifact was used. What is the chronometric date of the artifact or of an artifact it was found in association with? When archaeologists refer to time in the past, it is done with either relative or chronometric dates. Relative dates give the time of an event with reference to another event that is not worldwide in scale (Figure 5.20). They tell us simply that one thing is older or younger than another. They do not tell us when an event happened in years before the present. One common relative dating technique is called ceramic seriation (Figure 5.21). In frequency seriation, ceramic analysts document the style of ceramic vessels in each strata of a stratigraphic column. Vessel form, decoration, or even ceramic paste can be used to document ceramic style. Vessels or broken pieces of vessels ( sherds ) with these styles are then counted to get obtain their frequency in each strata.

Figure 5.20: Relative dating gives an archaeologist an idea of how old something is comparison to something else – sometimes this can be associated with a large range of dates as in the illustration here

Figure 5.21: Ceramic seriation is common method of relative dating. Because different styles of vessels were made at different times in the history of a site, archaeologists can use those styles as relative reference for chronological context

Ceramicists will then compare the number of different styles within each strata. This will reveal which styles appear earlier (deeper) in the stratigraphic column and which ones appear later (closer to the top). Ceramicists can then use these styles to date contexts in other areas of the site. A true frequency seriation relies not only on the presence or absence of ceramic styles to date a context but the ratio of frequencies between ceramic styles in any one strata.

Chronometric or absolute dates place events in their chronological position with reference to a universal time scale such as a calendar. All events given the same chronometric date will actually be contemporaneous. Chronometric dates are given in numbers of years since or before the beginning of some calendar system. For instance, 3000 BC was 3000 years before the starting point in the Gregorian calendar, which is the one that the U.S. and most other nations use today. Chronometric dates are close approximations of the true age of a deposit. Whenever possible, archaeologists obtain many samples from an ancient site to be tested with a variety of dating techniques. In this way, the chronological placement of a deposit can be more dependable. A date for an object, such as a human bone, is also more dependable when the bone itself is dated rather than something else physically associated with it in the same geological strata.

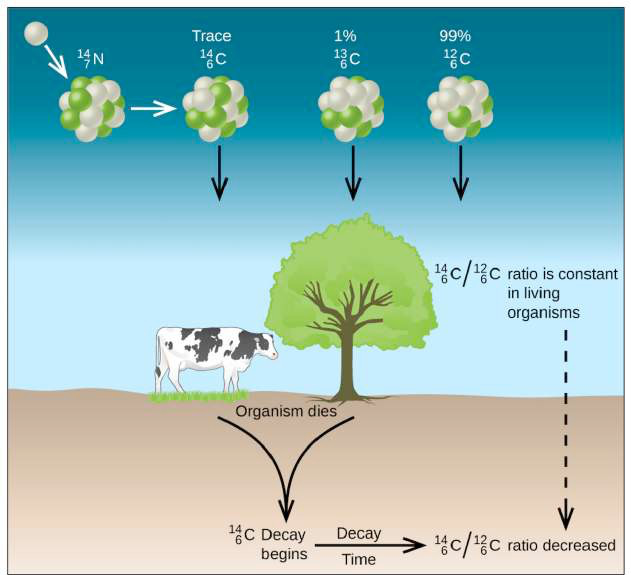

Most of the chronometric dating methods in use today are radiometric and based on knowledge of the rate at which certain radioactive isotopes within samples decay. Isotopes are specific forms of elements. The various isotopes of the same element differ in terms of atomic mass but have the same atomic number. In other words, they differ in the number of neutrons in their nuclei but have the same number of protons. The most commonly used radiometric dating method is radiocarbon dating (Figure 5.22). It is also called carbon-14 and C-14 dating. This technique is used to date the remains of organic materials. Organic living organisms consume C-14 during the course of their lifetimes. When an organism dies C-14 starts to decay at a regular rate that can be counted and used to infer age at death (i.e., when the organism stopped consuming C-14). Dating samples are usually charcoal, wood, bone, or shell, but any tissue that was ever alive can be dated.

Strata, and the artifacts and features they contain, are often dated using the concept of terminus post quem or the “limit after which” the latest dated object in a strata dates to. For example, if an archaeological stratum contained coins dating to 1488, 1525, 1613, and 1650, the terminus post quem would be the coin dated to 1650 or the latest date obtained from the evidence.

Use context refers to the context in which the artifact was used (Figure 5.23). What was the artifact used for or in what kind of context would the artifact be consumed? For example, the use context of a large ceramic jar with signs of charring on its exterior and found in a domestic trash deposit was likely related to cooking and food preparation.

Finally, spatial context refers to the relationship between the artifact and any other artifacts like it at the site or region where the artifact was found (Figure 5.24). Was the artifact one of a kind or was it like others found at the site or in the area? How does it relate to these other artifacts? Is it made from the same material? Does exhibit a higher quality of craftsmanship? The context of archaeological finds is what allows us to interpret them and understand their meaning.

Figure 5.22: Carbon dating is the most common form of chronometric or absolute dating in archaeology

Figure 5.23: A lithicist can determine the use context of these stone tools by studying their physical properties

Figure 5.24: Amphorae were a very common artifact at Classical sites located around the Aegean and Mediterranean Seas – they had a wide or expansive spatial context

Once excavation is completed and the features and objects have been analyzed according to contexts, archaeologists are responsible for interpreting and explaining the significance of the finds. The end result of every project is dissemination of all finds. This usually involves publication in multiple outlets (books, journal articles, chapters in edited volumes, and online publication). Publication ensures that what a team of archaeologists finds is available to other archaeologists and the general public. This allows other archaeologists to look over the data, agree, disagree, or build on the original interpretations and findings.

Explaining the past

Archaeologists have applied various intellectual frameworks to interpret their data and these frameworks are often referred to collectively as “archaeological theory”. There is no one singular theory of archaeology, but many, with different archaeologists believing that information should be interpreted in different ways. Throughout the history of the discipline, various trends of support for certain archaeological theories have emerged, peaked, and in some cases died out. Different archaeological theories differ on what the goals of the discipline are and how they can be achieved.

Early archaeologists interpreted their finds using the principles of antiquarianism. Antiquarians studied history with particular attention to ancient artifacts and manuscripts, as well as historical sites. They usually were wealthy people. They collected artifacts and displayed them in private collections (Figure 5.25) or bequeathed them to museums. Antiquarianism focused on the empirical evidence that existed for the understanding of the past, but were less concerned with the people behind the artifacts than with the artifacts themselves.

The late 1800s and early 1900s brought with them the first scientific archaeological investigations, and along with them, the advent of culture-history approaches. Archaeologists applying a culture-history approach grouped artifacts into distinct “cultures”. They wanted to determine the geographic spread and time span of these ancient cultures and to reconstruct the interactions and flow of ideas between them. Cultural history was closely related with the science of history. Cultural historians employed the normative model of culture, the principle that each culture has a set of norms governing human behavior. This meant that cultures could be distinguished by style: for example, if one excavated vessel is decorated with a triangular pattern, and another vessel with a wave pattern, they probably were made by different cultures. This kind of approach lead to a view of the past as a collection of different populations,

Figure 5.25: Ole Worm’s cabinet of curiosities, from Museum Wormianum, 1655 is an excellent example of an antiquarian collection.

classified by their differences and by their influences on each other. Changes in behavior could be explained by diffusion where new ideas moved across the landscape through social and economic ties from one culture to another. Noted culture historians included V. Gordon Childe in his earlier career and A.V. Kidder.

Neovolutionism attempted to explain the evolution of societies by drawing on Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution while discarding inaccuracies of previous theories of social evolutionism. Neoevolutionism is concerned with long-term, directional, evolutionary social change and with regular patterns of development that may be seen in unrelated, widely-separated cultures. Noted neoevolutionists included Leslie A. White, Julian Steward, and Marshal Sahlins. Many archaeologists left unsatisfied with culture history approaches and the mechanism of diffusion for culture change embraced Neoevolutionist theory.

In the 1960s, a number of younger American archaeologists, like Lewis Binford, rebelled against the culture-history approach. They proposed “New Archaeology”, which would be more “scientific” and “anthropological”. They came to see culture as a set of behavioral processes and traditions (later called processual archaeology ). Processualists borrowed from the natural sciences the idea of hypothesis testing and the scientific method. They believed archaeology had the potential to create overarching law-like statements that could be applied to all cultures (but not necessarily in an evolutionary way). They believed that an archaeologist should develop one or more hypotheses about a culture under study, and conduct excavations with the intention of testing these hypotheses against new evidence. They had also become frustrated with the previous generation’s emphasis on artifacts and archaeological cultures as opposed to the cultural processes that created them. It was becoming clear, largely through the evidence of anthropology, that ethnic groups and their development were not always entirely consistent with the cultures in the archaeological record.

In the 1980s, a new movement arose led by the British archaeologists Michael Shanks, Christopher Tilley, Daniel Miller and Ian Hodder. It questioned the processualist’s approach to science and impartiality by claiming that every archaeologist is in fact biased by his personal experience and background. Therefore, truly “scientific” archaeological work, and the creation of law-like statements, is difficult or impossible. This is especially true in archaeology where some archaeological experiments (i.e., excavations) could not be repeated by other archaeologists as the scientific method dictates. Proponents of this method, called post-processual archaeology, analyzed the material remains as well as themselves, their attitudes and opinions. The different approaches to archaeological evidence, which every person brings to his or her interpretation result in different constructs of the past for each individual. The benefit of this approach has been recognized in such fields as visitor interpretation, cultural resource management, and ethics in archaeology as well as fieldwork. It has also been seen to have parallels with culture history. The most recent theoretical approaches in archaeology focus on systems of power, how everyday practices contribute to the reproduction of social systems, ideology, gender, materiality, and actions of individuals in influencing cultural process.

Review of Learning Objectives

Archaeology is the sub-discipline of anthropology that uses material objects to study human culture. There are many different kinds of archaeology ranging from the prehistoric, to the ancient, to the historic, to the contemporary. All archaeology begins with a question and often involves hypothesis testing. Methods of archaeology include survey (sometimes using remote sensing), mapping, excavation, and various forms of analysis. A key issue for archaeologists is dating remains for which both relative and chronometric techniques can be applied. Archaeologists interpret their finds using a range of different theoretical frameworks.

Concept review

- List the different kinds of archaeology and their primary areas of focus.

- Discuss how archaeologists formulate their research before beginning excavation.

- List the primary methods of archaeological research.

- Identify and define the four different kinds of archaeological contexts.

- List and discuss the different theoretical frameworks that that archaeologists have used to understand the past.

Applying concepts

- If an archaeological context contains coins dating to 1588, 1595, and 1590-1625, what is terminus post quem for the context?

- Provide examples of an artifact, ecofact, and archaeological feature.

Archaeologists use the scientific method to study the material remains of people who lived in the past. However, there are people who portray themselves as experts or scientists, but ignore the scientific method in order to create false and extraordinary views of the past. This practice is known as pseudoscience (something that appears to be scientific, but is not). Identify examples of archaeological pseudoscience in popular culture and compare the methods, analysis, and interpretations of these pseudoscientists to archaeologists working in the same or similar areas of actual research.