1

Using Anthropological Perspectives

Learning Objectives

-

- Describe how anthropology differs from other fields that study humans

- Explain primary interests of the major subfields of anthropology

- Discuss practical uses of anthropology in solving contemporary problems

- Summarize practical benefits of studying anthropology

What Is Anthropology?

Anthropology is a social science that focuses on the study of what makes us human. The word “anthropology” comes from the combination of the Latin words anthropos meaning “human” and logia or logos, meaning “to study”. As social scientists, anthropologists use theory and method to generate qualitative and quantitative data in order to test hypotheses about specific questions they have about the human experience. These questions are far reaching and focus on aspects of the human body (biological anthropology), the human past (archaeology), human language (linguistics), and contemporary behaviors (cultural anthropology). Anthropologists may also work outside the university or research system and apply their skills to address social issues – this is called applied anthropology. While anthropology is similar to other social sciences since it uses the scientific method (Figure 1.1) to study human behavior, it’s also unique. Anthropology is distinguished because it’s holistic, relativistic, comparative, and focuses on the concept of human culture.

Anthropology is holistic because it takes a broad approach to understanding the human experience. For example, if a cultural anthropologist were focusing on the study of a specific behavior of a particular group of people, they would not examine that behavior in isolation – say in reference to social organization, politics, the economy, or psychology.

They would look at that behavior, and seek to understand it, in relation to all of these dimensions at once. That’s because human behaviors are informed by multiple dimensions of the human experience, and in order for an anthropologist to really understand a specific behavior, she must study it in relation to as many dimensions as possible. That is why in addition to formulating their own theory and method to understand the human experience, anthropologists also borrow from the other social sciences.

Figure 1.1: The scientific method is an ongoing process in anthropological study

A core concept in anthropology is cultural relativism. This is the idea that someone should not judge the behavior or beliefs of another culture using the standards from their own culture. In order to become culturally relative, we must learn to overcome our own ethnocentrism – the idea that the values and ideas of our own culture are “superior” or “natural” in comparison to those of other cultures. Ethnocentrism is not an inherently negative thing. We are all ethnocentric to an extent – we must be in order to live and succeed in our own culture. But if we truly want to understand why members of another culture are behaving in a certain way, we have to find a way to step outside of our own way of thinking and step into the mindset of another group of people. Suspending our ethnocentrism is easier said then done. Immersing yourself in another culture can be uncomfortable or even upsetting. Culture shock is a feeling of disorientation and anxiety that manifests itself in physical symptoms resulting from being placed in an unfamiliar culture. It is not uncommon for cultural anthropologists to experience culture shock, and it’s often mentioned in their personal journals or reflexive parts of their written ethnographies.

Anthropology is comparative because anthropologists do not study, analyze, and interpret what they learn about other cultures in isolation. After generating their data, anthropologists will compare it to data from other studies about other cultures in order to interpret what it might mean. These other cultures may not live in the same part of the world as the culture under study – they may not even exist in the same time period. In this way, anthropologists are able to see how cultures develop similar or different behaviors to solve the same problems that all humans face.

Finally, anthropology is unique for its focus on human culture. We define culture in this book as the learned and shared knowledge and behaviors of a human group. While short, this definition is deceptively simple and we will unpack the term in one of the following sections. Anthropologists study culture in four different ways – through bodies, material culture, language, and behavior. They can also apply what they learned to solve current social problems. We’ll now take a look at the four different ways anthropologists study culture, and the number of ways they can apply what they learn.

Biological anthropology

Biological anthropologists study how humans evolved from other animals (paleoanthropology) (Figure 1.2), how they adapt to different climates and environments (modern human variation), and how humans are related to other nonhuman primates like monkeys and other great apes (primatology). Biological anthropologists also study the relationship between biology and culture. Like all anthropologists, they are interested in explaining the similarities and differences that are found among humans across the world, but specifically in regard to the human body. Their research has shown that despite physical variation among humans across time and space, we are more similar to one another than we are different.

Figure 1.2: Paleoanthropology is a sub-field within biological anthropology that

studies the evolution of the human body from fossil hominids like these

Archaeology

Archaeologists study human culture by analyzing the things people make and leave behind (Figure 1.3). These things can include artifacts like pottery, textiles, stone tools, and metal ornaments. But they can also include architecture and modifications to landscape. They also integrate analysis from biological anthropology in order to study human bones and teeth to gain information on a culture’s diet, level of nutrition, and occurrence of disease. Archaeologists also study the remains of plants, animals, and soils in an effort to understand how people used and changed their natural environments. Archaeologists study humans living in time periods before the presence of writing (prehistoric archaeology). They study cultures that wrote texts, but generally lived before the period of European colonization in the 16th century (ancient archaeology). They also study cultures that lived in more recent times (historic archaeology), and even examine the artifacts we use today (contemporary archaeology and material and (culture studies) Archaeologists (like all anthropologists) are interested in comparing and explaining the similarities and differences between cultures across great periods of time and space.

Figure 1.3: Archaeologists perform excavation at the site of Çatalhöyük, Turkey to

answer questions about life in this ancient community

Linguistics

Linguistic anthropologists study human culture through systems of communication. Among other things, they are interested in how language is related to the way we think and perceive the world around us. They study the rules, lexicon, and sounds in a

particular language (descriptive linguistics), and how these may change over time (historical linguistics). They also study what we think about language, and how we use language in our current lives (socio-linguistics) (Figure 1.4). This includes the ways we

use language to build relationships, create or change identities, and create or maintain relations of power. Language is arguably the largest and most complex system of symbols that humans have ever created, and it is key to how we create, learn, and share our

culture.

Cultural anthropology

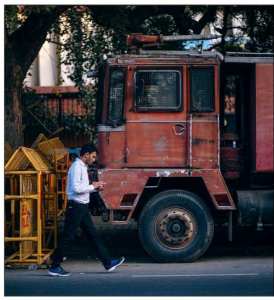

Cultural or sociocultural anthropologists study the culture of contemporary peoples. Like other anthropologists, their research begins with a specific question about the human behavior of a particular group of people. After gaining permission, they engage in

fieldwork where they live with the culture they are studying for a long period of time (Figure 1.5). This process is called ethnographic research. During this period they come to understand life the way that the people they are studying do. Specific questions may

involve a particular culture’s rites of passage ceremony for young boys or girls, how a culture constructs and categorizes gender, or how a non-western indigenous economy can become integrated into a global marketplace. When cultural anthropologists

complete their study they produce a published book-length manuscript called an ethnography.

Figure 1.4: One area of study in socio-linguistics is the different variations of language systems, or “dialects”, like the Standard American English dialects heard in different regions of the United States

Figure 1.5: Cultural anthropologists live and work with contemporary people in order to answer questions about human behavior and the human experience

Applied anthropology

Applied anthropologists use theory and method from one of the four sub-disciplines of anthropology to address social problems outside of the academic system. Probably the most commonly known kind of applied anthropologists are forensic anthropologists.

They use method and theory from biological anthropology to help law enforcement officials solve crimes that involve human bodies. Development anthropologists are cultural anthropologists who work with foreign governments and international agencies to help allocate funding in development nations. Medical anthropologists are trained as biological and cultural anthropologists. They study cultural perceptions of disease and nutrition, as well cultural practices related to health. They use their skills to address issues related to health and wellness in both industrial and non-industrial countries.

Corporate anthropologists apply theory and method from cultural anthropology to areas of business like marketing, advertising, product design, and internal efficiency (Figure 1.6). Finally, Cultural Resource Management (CRM) firms are comprised of archaeologists who work in private companies. When a construction company, or the state or federal government, wants to build anywhere in the U.S. that may contain cultural remains, CRM firms are asked to bid on the project for a contract. After the contract is agreed upon, the CRM firm performs the excavation, analyzes any finds, and relocates or stores any cultural material. CRM firms are responsible for about 80% of archaeological investigations undertaken every year in the U.S. Jobs for all applied anthropologists are growing and more opportunities become available as demand grows for anthropologists’ valuable skill sets.

Figure 1.6: Anthropologists who work in the business world are often called “corporate anthropologists,” like Dr. Genevieve Bell, known for her work at Intel on the intersection of cultural practice and technological development

Concepts of Culture

Defining culture

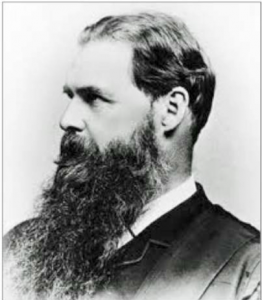

Even though culture is foundational concept in anthropology and one of the things that makes it unique among the social sciences, it has been defined in many ways over the years. While there have been many definitions of culture in the history of anthropological thought, we want to focus on two in particular because we believe they represent two ends of a spectrum that reflect an emphasis on quantitative vs. qualitative characteristics of the culture concept. One of the first definitions of culture within the discipline comes from Edward Burnett Tylor (Figure 1.7), often considered one of the founders of cultural anthropology.

Figure 1.7: Edward Burnett Tylor, the founder of academic anthropology

Tylor defined culture as follows:

“Culture, or civilization, … is that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art,

law, morals, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a

member of society” (Tylor, 1871:1).

At face value Tylor’s definition may seem appropriate and complete, but upon analysis it becomes worthy of critique. First, Tylor conflates culture with “civilization” or complex society of the late 19th century. This was an unfortunate common practice among cultural anthropologists of the time and something anthropologists stopped doing in the early years of the 20th century. Second, Tylor emphasizes the more quantitative aspects of what a culture is – that is, culture to Tylor is a group of categories that should be studied, tallied, and compared between cultures (i.e., “knowledge, belief, art, law, morals, custom,” etc.). Finally third, while Tylor references that culture is “acquired by man” (with the use of “man” now more than a little androcentric or male centered), he says nothing about how people learn culture or what culture does for them.

A different definition that focuses on the more qualitative characteristics of culture comes from the influential 20th century anthropologist, Clifford Geertz (Figure 1.8), who writes,

“The concept of culture I espouse…is essentially a semiotic one. Believing…that man is

an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun, I take culture to be

those webs, and the analysis of it to be therefore not an experimental science in search

of law but an interpretive one in search of meaning. It is explication I am after,

construing social expressions on their surface enigmatical.” (Geertz 1973:5)

Figure 1.8: Clifford Geertz, famous for his contributions to the theoretical view known as interpretive anthropology

Here Geertz emphasizes what culture does for people – it gives them the ability to understand the world around them – it gives them meaning – and in so doing creates a complicated web of symbols and behaviors. Geertz believes that it is the anthropologists’

job to understand how strands in that web connect, how peoples behaviors are “entangled” in that larger web of meaning, rather than to tally traits within preconceived categories of behavior then compare them to other cultures as Tylor proposes. As we

mentioned earlier, these definitions represent two ends of a spectrum; we might call them the quantitative and empirical (Tylor) vs. the qualitative and theoretical (Geertz). But is there a definition that accounts for both ends of the spectrum? Is there a place to

meet in the middle between empiricism and theory? We think so.

In this book we have defined culture as the learned and shared knowledge and behaviors of a human group. While this definition is short, it is not simple, and deserves some unpacking. We spend the rest of the chapter examining the culture concept in more detail.

Characteristics of culture

Cultural anthropologists Garrick Bailey and James Peoples (2014) use a similar definition of culture and present a useful strategy for unpacking the concept. We’d like to draw upon their work as we examine the concept of culture in more detail. Bailey and Peoples

argue culture is learned, shared, and consists of a body of knowledge (i.e., norms, values, symbols, cultural constructions, and worldview). One of the most important things to understand about culture is that culture is learned. We do not pass down cultural traits to our offspring in some biological way. A perfect example of this is language. We are not born with the ability to speak the language of the culture we are born into – we’re actually born with the ability to speak any language ever spoken, we just have to learn it. We learn most of our cultural behaviors from the time we are born through late childhood during a process called socialization or enculturation (Figure 1.9). Through observing, trial and error, and inference, we learn the appropriate

Figure 1.9: School children are socialized every day when they attend public school, and in the U.S., saying the pledge of allegiance is a kind of formal socialization

ways to act in our culture, what our culture values, what people we consider to be our family, where we think good and evil come from, and a whole host of other knowledge and behaviors. Because humans learn culture, it can spread very quickly. This means

cultural knowledge and behavior can lead to rapid social change – unlike genetic traits which take thousands of years to cause physical and perhaps behavioral changes in organisms.

Culture is shared. This simply means a group of people living in the same culture has similar ideas and behaviors that they transmit to one another. We can be part of many different cultures at the same time, and share different behaviors or knowledge with

members from different groups. These different groups of cultures are often referred to as sub-cultures (Figure 1.10), but we believe that term is problematic. It implies that cultures are hierarchical or nested within one another, perhaps with one culture’s

knowledge and behaviors being superior or taking primacy over others. We prefer to think of cultures as heterarchical. That is, they are all of equal importance, but the cultural knowledge and behavior of one culture may take primacy over another

depending on the context. For example, you are always part of many different cultures at any one time. You are part of a national culture, an ethnic culture, a professional culture, a social culture, and maybe even a religious culture. The way you act in any given situation will depend on the larger social context. Are you in your home country? Is the person you’re interacting with a friend, family member, employee, boss, or professor? Is the setting formal, casual, somber, celebratory? Depending on your answers to these

questions, you will draw upon multiple bodies of cultural knowledge to act accordingly. We explore these bodies of knowledge in more detail next.

Figure 1.10: These Star Trek cosplayers are part of a sub-culture in the U.S.

Culture consists of a body of knowledge, which leads to the creation of specific patterns of cultural behavior. These bodies of knowledge are composed of norms, values, symbols, cultural constructions, and worldviews.

Norms are shared ideas or expectations about how people should act in certain situations. They can sometimes be constraining, but they also add a layer of predictability to an otherwise unfamiliar situation. For example, how do you act when you meet

someone for the first time? Where should you sit at a family dinner? Should you take the seat next to someone on a public bus, or go to the empty row? The answer to these questions depends on the norms in your culture. In the U.S. we might shake someone’s

hand (Figure 1.11) when we meet him or her for the first time. At a family dinner, we know not to take the seat at the heads of the table, as they are usually reserved for family members with authority and respect. We would likely sit in the empty row on the bus

rather than sit next to a stranger. However, it is important to note that we don’t have to follow our cultures norms al the time. We can break them by accident or on purpose to make a statement about something. Something else that is important to know is that

norms are related to another category within a culture’s body of knowledge. Norms are the behavioral manifestation of a culture’s values, which we discuss next.

Figure 1.11: A gesture as simple as shaking hands is a cultural norm for many

Western people

Values are shared ideas about the most desirable way to act and live in a culture. They are the ultimate or ideal standard, against which all members of a culture should be judged. People whose behaviors embody these values are celebrated during life and

venerated after they die. For example, freedom is a value in the U.S. people who defend freedom in politics, social life, or the military are respected and celebrated. If a member of the armed services dies, on duty or retired, they are treated with an amount of respect

and pageantry that civilians are not (Figure 1.12). However, as with norms, values can also be ignored. They may guide individual and institutional behavior, but they do not determine it. Returning to the example of an armed service member, many service men

and women returning from active duty are not able to get the medical, psychological, and economic relief they need from the government to make their transition back to civilian life. Despite what our national values prescribe about the valor of service, federal

programs do not reflect those values.

Figure 1.12: This statue dedicated to the Marines who fought in WWII honors those who fought and died for American values

Symbols are the primary means through which we learn and share our culture. A symbol is simply something that stands for something else. As we’ve already mentioned, language is arguably the greatest and most complicated system of symbols that any

culture uses. Language is a system of speech sounds that are represented by visual symbols. But cultures use many more symbols outside of speech. Pictures, sounds, smells, shapes, gestures, colors, and anything else detectable by our senses can be paired with a

meaning and converted into a symbol (Figure 1.13). In the U.S. we equate a symbol of a red hexagon with the command “to stop”. We look to the American flag and know its 13 stripes symbolize the original 13 colonies and its 50 stars stand for the 50 states. We also

know the flag stands for something more abstract – the values of freedom and liberty that we regard as the ultimate standard living. However, it is important to remember that symbols – like norms and values – are culturally and contextually dependent. A red

hexagon does not mean, “to stop” in every culture. The American flag does not stand for liberty and freedom to someone who is not American. In addition, one symbol can mean something completely different depending on the context within the same culture. For example, a wink from a friend or co-worker to acknowledge an inside joke is quite different than a wink from a stranger across a crowded room at a party.

Cultural constructions are the cognitive structures people create in order to perceive and classify aspects of the natural and social world around them. Cultural constructions are best explained by example. One common cultural construction is how different

cultures classify what they can eat vs. what they can’t eat (Figure 1.14). In the U.S. for people who eat meat, it is okay to eat meat from animals like chickens, cows, pigs, and

Figure 1.13: Emoji’s are part of a symbol system whose signs are arbitrarily related to what they signify

Figure 1.14: The kinds of meat a culture finds appropriate to eat is an example of a cultural construction

fish. However, it is not okay to eat from horses, dogs, many kinds of reptiles, or other closely related primates like monkeys. Another universal cultural construct is kinship –or whom we classify as belonging to our family. How far out and back in time do you

recognize family relations? Can you name your great, great grandmother? Your second cousin once removed? Do you reckon kinship from either parent, or just your father’s side of the family? Finally, in the U.S. race is an important cultural construct that

significantly impacts health, diet, wealth, and social status. Depending on an arbitrary combination of physical characteristics (always including skin color), descent, and cultural practices federal, state, and social institutions force you into a category that

implicitly, and at one time explicitly, determines your rights and privileges vis-a-vis other citizens. We will examine race more closely in one of the biological chapters. Worldview is the final category within a cultural body of knowledge and possibly the most difficult to define.

Worldview refers to a particular philosophy of life or conception of the world that reflects the values, cultural constructions, and symbols of a culture. Do you believe other people are generally kind and helpful, or are they out to take what’s yours and hurt you? Where do good and evil come from? What is your purpose in life? Answers to these questions and more can be found in a culture’s worldview (Figure 1.15). Worldview can encompass values from a religious system, but it does not have to. Take for example a generalized contemporary American worldview. For many people it can be defined by a combination of Judeo-Christian values with secular principles. Worldviews, along with other components of cultural knowledge, help to guide a person’s behavior, which is the next aspect of our definition of culture.

Figure 1.15: Worldview shapes how we perceive the world around us, and our relationship to the people and things within it

It is important to understand that culture guides our behavior, but it does not determine how we act. We can always break our cultural norms and values. We can ignore cultural symbols, subscribe to some parts of our cultural worldview, and leave others behind. We always have a choice in how we behave, and we can make those choices consciously or subconsciously. It’s also important to remember that cultural groups are not monolithic wholes. That is, cultures are comprised of groups of individuals. Those individuals vary greatly in what they think and how they act. Their behavior may conform to some aspects of their cultural traditions, but also may diverge in some way. An important aspect of anthropological research is recognizing and documenting this conformity along with potential conflict within a group.

Related to this point, because cultures are comprised of individuals who are able to conform or conflict with cultural guidelines, cultures are dynamic. That is, cultures can and will change (Figure 1.16). No culture is static. Through internal and external processes, cultures inevitably change overtime.

Figure 1.16: Cultural is always changing with a constant ebb and flow of old and new ideas, behaviors, and material things

This ability for cultures to change brings us to our last point. The concept of culture is more than a simple analytical category – it is an evolutionary imperative. Culture – the ability for people to learned and pass down a body of knowledge and patterns of behavior

– was selected for in our evolutionary past. Culture is an adaptive mechanism. The ability of humans to come together and share ideas and behaviors using systems of symbols gave our hominid ancestors, and later early Homo sapiens, an evolutionary advantage

over other animals (Figure 1.17). Culture was and continues to be an advantageous evolutionary trait that enables us to survive, and that is quintessentially human.

Figure 1.17: Culture is an adaptive mechanism that was selected for because it helps early humans survive through cooperation

Studying and Doing Anthropology

Each semester we teach General Anthropology we experience a similar situation. Students come to us after the first few days, after a class they really enjoyed, or even when the semester is about to end, and they say something like, “I really loved this class

and found anthropology so interesting, but what can I do with it outside of school?”. We like to answer with a question of our own, “what CAN’T you do with a degree in anthropology?!”

In all sincerity, we know it’s a serious question. Students feel a lot of pressure to choose the right major – something that will support them, something what will lead to a job that will help them pay for school, something their parents approve of, something that’s

personally rewarding. The truth is, whatever you want to do, a degree in anthropology can help you get there, and help you succeed when you arrive (Figure 1.18).

Anthropology teaches you how to research, analyze, and interpret complex datasets of natural and social phenomena. It promotes critical thinking by asking you to analyze and interpret different positions in an argument in order to arrive at your own objective and informed conclusion with support from material and behavioral evidence. It also teaches you how to identify and understand the norms, values, cultural constructions, symbols, and worldviews of other cultures. This allows you to see where different people are

coming from, help you communicate better, and arrive at a mutually beneficial resolution to a problem or negotiation.

Anthropologists are employed in a number of academic and private institutions. Of course they teach in colleges and universities, but outside the university anthropologists work in government agencies, private businesses, community organizations, museums,

independent research institutes, service organizations, and the media. Actually, more than half of all anthropologists work in organizations outside the university. Companies that employ anthropologists include Netflix, Intel, Google, Match.com, and Reddit.

Governmental institutions that employ anthropologists include the Smithsonian Institution, Department of Veterans Affairs, National Park Service, and the Centers for Disease Control.

Finally, on a more existential note, it’s important to remember that what you choose as your college major does not determine what your career will be. In fact, according to recent studies only 27% of graduates get a job and begin a career in a field remotely

related to their major. Furthermore, it’s a myth that early careers in anthropology are severely underpaid. According to PayScale.com’s major-specific average earnings for early career jobs, anthropologists with only a bachelors still average $40,000 a year.

Finally, if you’re looking for job security, you’re unfortunately unlikely to find it anywhere. The job market is the not same as it was for your parents or grandparents. Jobs are not secure and work conditions are always changing. If anything, you need a major that teaches you how to identify, analyze, and interpret market trends – a major that teaches you the value of having a diverse range of skills – a major that shows you how organisms can adapt to new environments in order to survive. That major is anthropology.

Figure 1.18: A major or minor in anthropology advances any academic or professional career

Review of Learning Objectives

Anthropology is a social science that focuses on the study of humans. It is unique among other social sciences in its holistic, comparative, and relativistic approach to the study of humans and their culture. Anthropology is divided into four sub-disciplines that focus on the study of the human body (biological anthropology), material culture (archaeology), language (linguistics), and the behavior of living humans (cultural anthropology). Sometimes considered a fifth sub-discipline, applied anthropology focuses on using

method and theory from the four sub-disciplines to address current social problems. Examples of applied anthropologists include medical anthropologists, development anthropologists, forensics, corporate anthropologists, and cultural resource managers. An

anthropological perspective is valuable to any career inside or outside the university system because it promotes critical thinking, communication skills, and global competence through the application of the culture concept.

References cited

Bailey, Garrick, and James Peoples. 2014. Essentials of Cultural Anthropology. Third

Edition. Wadsworth Cengage Publishing, Belmont, CA.

Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. Basic Books, Inc., New York.

Tylor, Edward Burnett. 1871. Primitive Culture. Vol. 1. John Murray, London.

Concept review

Concept review

- Identify the four aspects of anthropology that make it unique from other disciplines in the social sciences.

- List the five major sub-fields of anthropology.

- Define the concept of culture.

- Describe the main characteristics of culture.

Applying concepts

- Norms are an integral component of any culture. They are social rules that regulate behavior and create expectations during social interaction. Identify and discuss three norms of behavior that may be unique to a culture to which you belong.

- Cultural constructions are the cognitive structures people create in order to perceive and classify aspects of the natural and social world around them. Identify and discuss at least one example of a cultural construction from a culture to which you belong.

- Culture shock is a feeling of disorientation and anxiety that manifests itself in physical symptoms resulting from being placed in an unfamiliar culture. Anyone who has traveled outside his or her hometown has experienced culture shock at least to a slight degree. Discuss a situation where you experienced the feeling of culture shock and why you think it occurred.