Chapter 20 Electric Current, Resistance, and Ohm’s Law

20.2 Ohm’s Law: Resistance and Simple Circuits

Summary

- Explain the origin of Ohm’s law.

- Calculate voltages, currents, or resistances with Ohm’s law.

- Explain what an ohmic material is.

- Describe a simple circuit.

What drives current? We can think of various devices—such as batteries, generators, wall outlets, and so on—which are necessary to maintain a current. All such devices create a potential difference and are loosely referred to as voltage sources. When a voltage source is connected to a conductor, it applies a potential difference ![]() that creates an electric field. The electric field in turn exerts force on charges, causing current.

that creates an electric field. The electric field in turn exerts force on charges, causing current.

Ohm’s Law

The current that flows through most substances is directly proportional to the voltage ![]() applied to it. The German physicist Georg Simon Ohm (1787–1854) was the first to demonstrate experimentally that the current in a metal wire is directly proportional to the voltage applied:

applied to it. The German physicist Georg Simon Ohm (1787–1854) was the first to demonstrate experimentally that the current in a metal wire is directly proportional to the voltage applied:

This important relationship is known as Ohm’s law. It can be viewed as a cause-and-effect relationship, with voltage the cause and current the effect. This is an empirical law like that for friction—an experimentally observed phenomenon. Such a linear relationship doesn’t always occur.

Resistance and Simple Circuits

If voltage drives current, what impedes it? The electric property that impedes current (crudely similar to friction and air resistance) is called resistance RR size 12{R} {}. Collisions of moving charges with atoms and molecules in a substance transfer energy to the substance and limit current. Resistance is defined as inversely proportional to current, or

Thus, for example, current is cut in half if resistance doubles. Combining the relationships of current to voltage and current to resistance gives

This relationship is also called Ohm’s law. Ohm’s law in this form really defines resistance for certain materials. Ohm’s law (like Hooke’s law) is not universally valid. The many substances for which Ohm’s law holds are called ohmic. These include good conductors like copper and aluminum, and some poor conductors under certain circumstances. Ohmic materials have a resistance ![]() that is independent of voltage

that is independent of voltage ![]() and current

and current ![]() . An object that has simple resistance is called a resistor, even if its resistance is small. The unit for resistance is an ohm and is given the symbol

. An object that has simple resistance is called a resistor, even if its resistance is small. The unit for resistance is an ohm and is given the symbol ![]() (upper case Greek omega). Rearranging

(upper case Greek omega). Rearranging ![]() gives

gives ![]() , and so the units of resistance are 1 ohm = 1 volt per ampere:

, and so the units of resistance are 1 ohm = 1 volt per ampere:

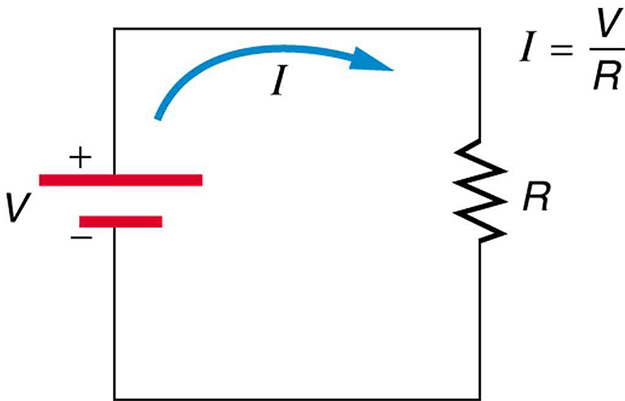

Figure 1 shows the schematic for a simple circuit. A simple circuit has a single voltage source and a single resistor. The wires connecting the voltage source to the resistor can be assumed to have negligible resistance, or their resistance can be included in ![]() .

.

Example 1: Calculating Resistance: An Automobile Headlight

What is the resistance of an automobile headlight through which 2.50 A flows when 12.0 V is applied to it?

Strategy

We can rearrange Ohm’s law as stated by ![]() and use it to find the resistance.

and use it to find the resistance.

Solution

Rearranging ![]() and substituting known values gives

and substituting known values gives

Discussion

This is a relatively small resistance, but it is larger than the cold resistance of the headlight. As we shall see in Chapter 20.3 Resistance and Resistivity, resistance usually increases with temperature, and so the bulb has a lower resistance when it is first switched on and will draw considerably more current during its brief warm-up period.

Resistances range over many orders of magnitude. Some ceramic insulators, such as those used to support power lines, have resistances of ![]() or more. A dry person may have a hand-to-foot resistance of

or more. A dry person may have a hand-to-foot resistance of ![]() , whereas the resistance of the human heart is about

, whereas the resistance of the human heart is about ![]() . A meter-long piece of large-diameter copper wire may have a resistance of

. A meter-long piece of large-diameter copper wire may have a resistance of ![]() , and superconductors have no resistance at all (they are non-ohmic). Resistance is related to the shape of an object and the material of which it is composed, as will be seen in Chapter 20.3 Resistance and Resistivity.

, and superconductors have no resistance at all (they are non-ohmic). Resistance is related to the shape of an object and the material of which it is composed, as will be seen in Chapter 20.3 Resistance and Resistivity.

Additional insight is gained by solving ![]() yielding

yielding

This expression for ![]() can be interpreted as the voltage drop across a resistor produced by the flow of current

can be interpreted as the voltage drop across a resistor produced by the flow of current ![]() . The phrase

. The phrase ![]() drop is often used for this voltage. For instance, the headlight in Example 1 has an

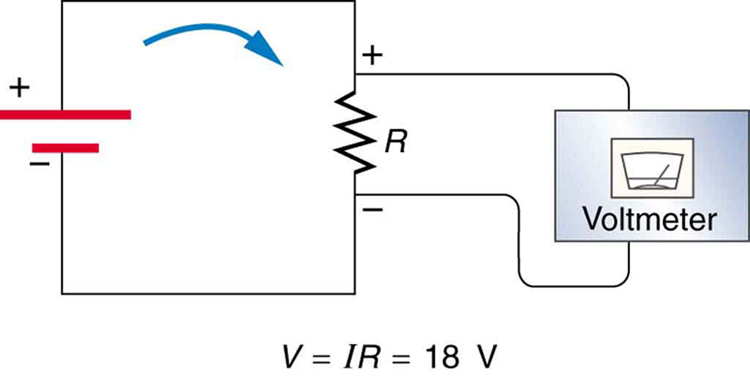

drop is often used for this voltage. For instance, the headlight in Example 1 has an ![]() drop of 12.0 V. If voltage is measured at various points in a circuit, it will be seen to increase at the voltage source and decrease at the resistor. Voltage is similar to fluid pressure. The voltage source is like a pump, creating a pressure difference, causing current—the flow of charge. The resistor is like a pipe that reduces pressure and limits flow because of its resistance. Conservation of energy has important consequences here. The voltage source supplies energy (causing an electric field and a current), and the resistor converts it to another form (such as thermal energy). In a simple circuit (one with a single simple resistor), the voltage supplied by the source equals the voltage drop across the resistor, since

drop of 12.0 V. If voltage is measured at various points in a circuit, it will be seen to increase at the voltage source and decrease at the resistor. Voltage is similar to fluid pressure. The voltage source is like a pump, creating a pressure difference, causing current—the flow of charge. The resistor is like a pipe that reduces pressure and limits flow because of its resistance. Conservation of energy has important consequences here. The voltage source supplies energy (causing an electric field and a current), and the resistor converts it to another form (such as thermal energy). In a simple circuit (one with a single simple resistor), the voltage supplied by the source equals the voltage drop across the resistor, since ![]() , and the same

, and the same ![]() flows through each. Thus the energy supplied by the voltage source and the energy converted by the resistor are equal. (See Figure 2.)

flows through each. Thus the energy supplied by the voltage source and the energy converted by the resistor are equal. (See Figure 2.)

Making Connections: Conservation of Energy

In a simple electrical circuit, the sole resistor converts energy supplied by the source into another form. Conservation of energy is evidenced here by the fact that all of the energy supplied by the source is converted to another form by the resistor alone. We will find that conservation of energy has other important applications in circuits and is a powerful tool in circuit analysis.

PhET Explorations: Ohm’s Law

See how the equation form of Ohm’s law relates to a simple circuit. Adjust the voltage and resistance, and see the current change according to Ohm’s law. The sizes of the symbols in the equation change to match the circuit diagram.

Section Summary

- A simple circuit is one in which there is a single voltage source and a single resistance.

- One statement of Ohm’s law gives the relationship between current

, voltage

, voltage  , and resistance

, and resistance  in a simple circuit to be

in a simple circuit to be  .

. - Resistance has units of ohms (

), related to volts and amperes by

), related to volts and amperes by  .

. - There is a voltage or

drop across a resistor, caused by the current flowing through it, given by

drop across a resistor, caused by the current flowing through it, given by  .

.

Conceptual Questions

1: The ![]() drop across a resistor means that there is a change in potential or voltage across the resistor. Is there any change in current as it passes through a resistor? Explain.

drop across a resistor means that there is a change in potential or voltage across the resistor. Is there any change in current as it passes through a resistor? Explain.

2: How is the ![]() drop in a resistor similar to the pressure drop in a fluid flowing through a pipe?

drop in a resistor similar to the pressure drop in a fluid flowing through a pipe?

Problems & Exercises

1: What current flows through the bulb of a 3.00-V flashlight when its hot resistance is ![]() ?

?

2: Calculate the effective resistance of a pocket calculator that has a 1.35-V battery and through which 0.200 mA flows.

3: What is the effective resistance of a car’s starter motor when 150 A flows through it as the car battery applies 11.0 V to the motor?

4: How many volts are supplied to operate an indicator light on a DVD player that has a resistance of ![]() , given that 25.0 mA passes through it?

, given that 25.0 mA passes through it?

5: (a) Find the voltage drop in an extension cord having a ![]() resistance and through which 5.00 A is flowing. (b) A cheaper cord utilizes thinner wire and has a resistance of

resistance and through which 5.00 A is flowing. (b) A cheaper cord utilizes thinner wire and has a resistance of ![]() . What is the voltage drop in it when 5.00 A flows? (c) Why is the voltage to whatever appliance is being used reduced by this amount? What is the effect on the appliance?

. What is the voltage drop in it when 5.00 A flows? (c) Why is the voltage to whatever appliance is being used reduced by this amount? What is the effect on the appliance?

6: A power transmission line is hung from metal towers with glass insulators having a resistance of ![]() . What current flows through the insulator if the voltage is 200 kV? (Some high-voltage lines are DC.)

. What current flows through the insulator if the voltage is 200 kV? (Some high-voltage lines are DC.)

Glossary

- Ohm’s law

- an empirical relation stating that the current I is proportional to the potential difference V, ∝ V; it is often written as I = V/R, where R is the resistance

- resistance

- the electric property that impedes current; for ohmic materials, it is the ratio of voltage to current, R = V/I

- ohm

- the unit of resistance, given by 1Ω = 1 V/A

- ohmic

- a type of a material for which Ohm’s law is valid

- simple circuit

- a circuit with a single voltage source and a single resistor

Solutions

Problems & Exercises

1: 0.833 A

3: ![]()

5: (a) 0.300 V

(b) 1.50 V

(c) The voltage supplied to whatever appliance is being used is reduced because the total voltage drop from the wall to the final output of the appliance is fixed. Thus, if the voltage drop across the extension cord is large, the voltage drop across the appliance is significantly decreased, so the power output by the appliance can be significantly decreased, reducing the ability of the appliance to work properly.