Latin American Artistic Expression

When used in reference to the colonial, the art is usually analyzed based on the influence that it had during its time, or the way that the art captures the ideology of the colonial era.

For example, religious images produced to represent the “benefits” of colonization included the construction of the legend and image of the Virgen de Guadalupe—a Marian image that was first seen/shown in Mexico and the legend of which was crucial in securing greater conversion of the Indigenous population to Catholicism throughout Latin America.

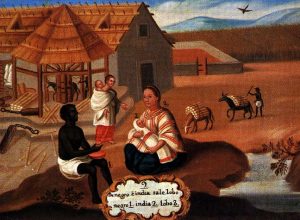

But, also powerful were the colonial images that we covered during Module 1. The images of the Casta System Paintings, alongside strategic typographical images of important port cities, such as early paintings of portraits of the colonial port city of Havana.

![The Piazza at Havana (1762) by Dominic Serres the Elder [Public Domain]. A depiction of an episode from the last major operation of the Seven Years War, 1756-63. It was part of England's offensive against Spain when she entered the war in support of France late in 1761. The British Government's response was immediately to plan large offensive amphibious operations against Spanish overseas possessions, particularly Havana, the capital of the western dominions and Manila, the capital of the eastern. Havana needed large forces for its capture and early in 1762 ships and troops were dispatched under Admiral Sir George Pocock and General the Earl of Albemarle. The force which descended on Cuba consisted of 22 ships of the line, four 50-gun ships, three 40s, a dozen frigates and a dozen sloops and bomb vessels. In addition there were troopships, storeships, and hospital ships. Pocock took this great fleet of about 180 sail through the dangerous Old Bahama Strait, from Jamaica, to take Havana by surprise. Havana, on Cuba's north coast, was guarded by the elevated Morro Castle which commanded both the entrance to its fine harbour, immediately to the west, and the town on the west side of the bay. This is a view of the 'Piazza' of Havana under occupation, (a now unaccountable Italianization in the received title, since it should be 'Plaza' in Spanish) showing the buildings and emptied-out open space bathed in brilliant sunlight. A group of three British sailors stand in shadow in the left foreground, with two more visible beyond the fountain. A platoon of soldiers in red jackets drills in the sunshine in the distance. The painting was one of a pair with 'The Cathedral at Havana, August-September 1762', BHC0417. For further details on the capture of Havana and the other paintings in this series, see BHC0408.The series in fact consists of two groups, six larger paintings with naval emphasis, and five smaller ones (including this) which focus more on the army and the town. Since they are all of Keppel family provenance, it is assumed that the naval ones were painted for Augustus Keppel, the naval second-in-command, and the others for his older brother George, Earl of Albemarle, the overall army commander.](https://pressbooks.online.ucf.edu/app/uploads/sites/99/2019/09/640px-Dominic_Serres_the_Elder_-_The_Piazza_at_Havana-300x206.jpg)

The goal and purpose of colonial paintings was to capture the magnitude of the wealth and power of colonial society. Keep in mind that during the colonial period only the rich and the powerful were captured in portraits (particularly the nobility and the wealthy that had settled in the Americas). The colonial era’s portraiture were at times used to show off the vast amount of land controlled by a colonial family, or to showcase the number of slaves and servants that they owned, alongside the vast amounts of livestock.

The average person during the colonial period without land, title, or wealth would not be able to afford being painted, and as such there are few representations of the perspective and experiences of average people during the colonial period—unless they were being represented by their master/owners.

Well into the 20th century both portraits and professional pictures were very important markers of wealth (that is why most Latin American middle class families would by the 19th and 20th century invest in both elaborate celebrations as well as professional portraits and professional photography of their weddings, baptisms, Sweet 15 birthdays (for their daughters). The desire to professionally reproduce and to prominently display these portraits and later photographs are an example of what remained of the legacy of marking one’s power via visual representations of one’s family and wealth.

As covered in Module 2, which focused on the Latino Imaginary and the Latino Imagined Community and the history of terms like Latin America, Latino/Latina and LatinX—the identity categories and the label Latin American/Latino-a-X have historically been in flux; open to being challenged in order to consider the limitations and the benefits of thinking of Latin American art as a shared artistic tradition.

19th and 20th Century Latin American Art marked by Independence Struggle

Most scholars and art historians today consider a Latin American artistic tradition as one that is marked by the multiple political and nationalist movements of the 19th and 20th century. These were primarily movements for independence and later for social struggles throughout the region (Mexico, the Caribbean, Central and South America— predominantly regions colonized by the Spanish, but also the Portuguese.

Today, Latin American art is also marked by how artists within these regions are working within the confines of globalization, and the ways artists are often migrating across nations; living and producing outside of their home countries of origin and thereby give meaning to what it means to be more than a national painter, but to instead be a Latin American artist, working within a Latin American artistic tradition that is simultaneously national, regional, international and global.

In short, Latin American art can be defined as artistic production that is the byproduct of multiple physical, political and aesthetic movements within the regions that are classified as being Latin America– and these movements are simultaneously influenced by global forces.

Take for example, the work of Mexican artists Frida Kahlo, or Diego Rivera (1920s to 1950s), or the Cuban poet Jose Marti (1880s), the Columbian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and even the contemporary Puerto Rican Hip Hop artists Calle 13—Just to name a few.

All of the artists mentioned above have been shaped by artistic movements that have been powerful because of the overall movement’s ability to merge traditional references, as well as unique postcolonial cultural reference and aesthetics.

The similarity between 19th and 20th Century Latin American artists can be said to include a legacy of engagement with specific historical and political debates about power within each of their respective national contexts.

Also, within their own respective era, these artists share the ability to keep their hand on the pulse of global and international political trends. For example, the influence of the Russian revolution and of the Mexican civil war can not be ignored for either Frida Kahlo or Diego Rivera. For Marti, publishing his most important work outside of Cuba in exile and concerned over U.S. annexation of the island meant that he was in conversation with both an international cohort of post-colonial writers and rebel fighters that were deeply committed to notions of freedom and equality, as well as anti-U.S. expansion in Latin America. By the twentieth century the magical realism of Gabriel Garcia Marquez captured the aesthetics of a uniquely Columbian world view that simultaneously resonated with a hemispheric sense of moving towards greater freedom of thought and expression following global civil unrest (1960s and 1970s) which led to the rise of the postmodern narrative forms in Europe and the U.S.

At the core of Latin American and LatinX art since the 1920s has been the combination of navigating and strategically utilizing the myth of an imagined community, the ability to creatively contend that references internal national dilemmas and debates, and the ability to speak to and to be heard within the global international political sphere.

As such, Latin American/LatinX artistic movements are less about the specific use of a series of images, or the abundance of colors, or the identifiable cultural themes. Instead it has been more about what images, colors and cultural themes mean to people, within an era, socially and politically. And, how the artist can create a visual and emotional language in which ideas about what moves and shapes a region and its people, societies and histories are communicated first and foremost among the population within the nation/region and then with the rest of the planet.