Chapter 9: Post-modernism

What is Postmodernism?

Paul Jurczak

We are currently living in a historical period called “Postmodern.” What we call “Postmodern” is simply what happens after the historical period called “Modern.” In the historical development of Western philosophy, we can see various major transitions. What is typically called “modern” philosophy starts with Descartes around the year 1630. Descartes marks a departure from the older Medieval Philosophy that had dominated European thinking. Medieval thought is marked by its adherence to authorities: the Bible and Plato/Aristotle. With the development of the Protestant Reformation (16th century) the reliance on religious authorities was undermined. As the various Protestant churches developed and fought for power with the older Catholic Church, it became unclear which church (if any) might actually have a correct understanding of Christianity. Also with the advances of science, the older Aristotelian model of the world was collapsing. This problem led Descartes and many other European thinkers away from reliance on religious and classical authority. Descartes is “modern” because he refuses to rely on older authorities and, instead, bases his arguments in human reason.

Thus, Modernism is the recognition of the limits of older authorities and the reliance, first and foremost, on human reason.As this “modern” world-view develops, it includes the historical era called the “Enlightenment” with its emphasis on the “universal” values of liberal, secular, democratic Europe and North America. The list of great “modern” thinkers usually includes such men as Galileo, John Locke, Immanuel Kant, and Isaac Newton. The “modern” way of thinking culminates in the late 19th century with a great wave of optimism; the Western world believed that their own way of rational-scientific thinking was transforming the world into a paradise of freedom and technological mastery.

That optimism collapsed in the first half of the 20th century. World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II collectively functioned as an on-going crisis. By the end of the First World War (1914-18) France and been economically devastated, the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian Empires had collapsed, Germany was in ruins, the Russian Empire had crumbled and some 15 to 20 million people had died in Europe as a result of the war. Then came the Great Depression (1929-1940) which was the worst economic collapse in modern history. It left tens of millions of people without work or income. Then World War Two (1939-1945) concluded with some 60 or 70 million deaths. The rational-scientific methods of the Western world culminated in atomic bombs capable of destroying entire cities. The willingness of the “modern” world to engage in a “rational” and highly technological frenzy of self-destruction was horrifically obvious. By 1945 the world of the “modern” lay in ruins throughout Europe and much of the rest of the world.

The Postmodern world began developing in the ruins of the Modern

Some late modern thinkers had seen cracks in the structure of the modern. Soren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) saw his world as increasingly de-personalized. Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) saw that the modern world had turned most of Europe into a mere “herd” that had lost its independent spirit. Despite these keen early observers, Postmodernism does not begin until after World War II. The “modern” faith in universal values of progress, science, and democracy had left much of the world in ruins.

Another crisis motivated the collapse of the modern; 20th century science was discovering its own limits. Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle was first introduced in 1927. Werner Heisenberg was an early developer of Quantum Physics. He proved that the more precisely the position of some atomic particle is determined, the less precisely its momentum can be known, and vice versa. This inability to know was NOT some lack of human ability; the human sciences were not in some way needing to be improved. Heisenberg saw the world as a place in which some things are, simply, not knowable. The problem of photons is another example of how the world itself is beyond human reason. Photons are effectively particles of light when measured one way and effectively waves when measured in another manner. So, the “true” identity of light seems to depend on how we observe rather than on some stable fundamental reality. A whole series of discoveries in physics during the 20th century undermined the scientific certainty of the “Modern” world. The most advanced physics of the 20th century was proving that the nature of ultimate reality was itself uncertain. This problem irritated Albert Einstein (1879-1955) who never fully accepted that some things would forever be unknowable. In this sense, Einstein tried to maintain the values of the modern world, but eventually it became evident that human reason has limits.

Although there are many major markers of our “Postmodern” world, in this chapter we will look at four: 1) the rejection of Grand Narratives, and the subsequent re-structuring of the world as 2), “pastiche”, “simulacra,” and as schizophrenic and 3), the undermining of traditional power relations through Deconstruction and 4) Feminism.

The rejection of Grand Narratives

In an important way, the “Modern” world had valued universal reason as the key to human fulfillment, but after World War II the Western conception of “reason” itself came to be questioned. Postmodern thinking is often associated with a rejection of grand narratives like “progress,” “modernity,” and “reason.” One of the early proponents of Postmodernism was the French philosopher Jean-Francois Lyotard (1924-1998). He claimed that cultures cohere, in part, because people within a specific culture believe in a dominant narrative. For most Christians of the Middle Ages that narrative was told in the Bible. For the people of Ancient Greece, their dominant narrative was told by Homer in The Iliad and The Odyssey. For the peoples of Europe and North America living at the end of the 19th century their dominant narrative was that of science, democracy, and rational thought. Even the radical 19th century ideals of “Communism” are part of that older (modern) culture. Karl Marx’s narrative of the collective workers of the world overthrowing their capitalist masters and re-building the world as the “workers’ paradise” had been a dominant narrative for the Soviet Union and Communist China; Communism is now seen as just one of many old-fashioned stories that has proven itself ineffective. Grand narratives are understood by Postmodernists as collective myths that never had a reality; grand narratives were attractive and widely believed but they were, at best, collective delusions and, at worst, impositions of power that went unnoticed. Once dominant narratives are shattered, people enter into a period of great uncertainty, groping for meanings and, perhaps, cherishing the “good old days” when they had a single comprehensive narrative that gave their lives meaning. However, the end of traditional meaning also produces the opportunity for people to create new meanings for themselves.

Postmodernism in the world—pastiche & the movies

With Postmodernism, we leave the certainty of a single, integrated, and sense-making narrative, and we enter into a period cut adrift from certainty, plunged into “multiple, incompatible, heterogeneous, fragmented, contradictory and ambivalent” meanings. The loss of a dominate narrative leaves people disconnected from each other, relying on smaller stories of identity like race, social standing, or hobbies that can only bring smaller groups of people together. Frederic Jameson (b. 1934) sees our Postmodern world as one in which cultures are dislocated and language communities are fragmented; each profession is increasingly cut off from others by its own peculiar jargon and private codes of meaning. We are unable to map our world as it breaks into innumerable minor cliques and tribes. A word that is often used to describe this new world is “pastiche”—a creative work (like a novel or movie) that openly imitates previous works by other creators. The “pastiche” relies on its readers/viewers sharing the author’s cultural knowledge.

The well-known film, Blade Runner (1982), takes up and make clear the idea of a “pastiche.” In the film, the language on the streets is known as “Cityspeak” and the main character (Deckard) says, “That gibberish he talked was Cityspeak, gutter talk, a mishmash of Japanese, Spanish, German what have you.” In this way, we have the fracturing of language and communities into a pastiche. Another example of this pastiche occurs early in the movie The Matrix (1999). The main character (Neo) happens to own a copy of an important Postmodern book of philosophy: Simulacra and Simulation by Jean Baudrillard (1981). Neo hides copies of his illicit computer files within this book. Morpheus quotes from the book when he speaks to Neo about the “desert of the real.” One doesn’t need to know this book in order to appreciate the movie, but for alert viewers the book functions not only as a “pastiche” (a quotation from another domain) but also as a sign of another important postmodern theme in the movie: how we replace reality and meaning with symbols and signs such that reality becomes a simulation of reality. In The Matrix Neo sells illicit computer files that function to give people experience; those experiences are merely simulations of “real” experiences. But once those simulations become so real that one cannot distinguish reality from simulation we have no longer a mere “simulation,” we have a “simulacrum.”

In the movie Blade Runner, the main character (Deckard) is employed to hunt down a group of “replicants” who were created to do dangerous work in the outer parts of our solar system, however a group of replicants has escaped and returned to Los Angeles (the city of angles) to confront their maker: Tyrell of the Tyrell Corporation. The replicants are themselves so close to real that it is almost impossible to distinguish them from real humans. They display intelligence, loyalty, anger, mercy and all those other human attributes, even philosophizing about the meaning of their lives. Thus, the replicants are a simulation that are as real as the humans they are meant to simulate; they are “simulacra.” At the end of the movie we are left with a disturbing possibility that our main character (Deckard) has fallen in love with a replicant and is, himself, probably a replicant.

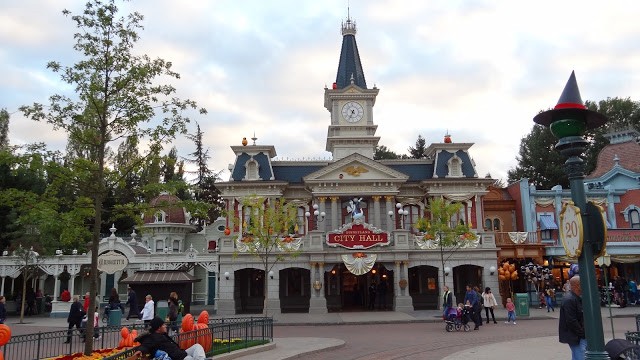

“Simulacra” (singular form of the plural “simulacrum”) is a Latin word that means similarity or likeness. It implies a reproduction of some original object. But in the Postmodern world it takes on a more disturbing meaning. At some point, our reproductions become so much like the originals that it no longer makes sense to distinguish the original from its copy. The simulacrum can then go on to take the place of the original. The Disney theme parks are often referred to by postmodern thinkers as an example of this replacement function. The Italian writer Umberto Eco says of the various Disney parks that “we not only enjoy a perfect imitation, we also enjoy the conviction that imitation has reached its apex and afterwards reality will always be inferior to it” (Travels in Hyperreality). Thus, we have the comment in the previous paragraph by Morpheus in The Matrix (quoting Jean Baudrillard)—the “desert of the real.” Reality becomes insufficiently entertaining or engaging for us; we seek a hyper- reality in which to spend our time. Disney’s “Main Street, U.S.A.” is Mr. Walt Disney’s idealized version of an early 20th century main street in a mid-sized, Midwestern town. But in Disneyland it is better: there is no crime, no liter, no homelessness, no dishonest businessmen or swindlers.

Another example that may help us understand the “simulacrum” is to think about money. Originally banks kept large amounts of gold and silver to ensure the value of our paper money. By the late 20th century those same banks mostly kept computer records that functioned in the place of silver and gold. When a person needed to buy some object, they could go to the bank and obtain paper money: cash. But today, many people use credit/debit cards (or their smart phones) to pay for the things they buy. Paper money and gold are frequently totally ignored; some stores in Europe have tried to only allow electronic transactions. Thus, the computer code that was originally a “simulation” of cash money (which was originally a “simulation” of gold and silver) is, today for many people, more real than cash. Our debit/credit cards are now “real” money; our credit/debit cards are a “simulacrum.”

In the movie Her (2013), the main character (Theodore Twombly) has a job writing love letters for people who feel incapable of writing such letters themselves. He falls in love with the operating system of his computer (like Siri or Alexa). As a writer of love letters to be used by people he does not know, the main character shows that an absence of personal relation does not eliminate the need for intimacy. Even a love letter written by a stranger and given to another stranger has meaning. This distancing of intimacy is then pushed even further in a love affair between a human male (Theodore) and the operating system of his computer. A set of complex computer codes are able to simulate an intimate relation to such an extent that Theodore’s relation with his computer is his intimate relation; for Theodore, his computer’s simulation of intimacy is so much like real intimacy that he falls in love with his computer (the “simulacrum”).

The Postmodern as schizophrenic

Another major symptom of postmodern existence (the first being Lyotard’s skepticism of grand narratives) is Frederic Jameson’s conception of the “schizophrenic” nature of contemporary life. Jameson borrows from Jacques Lacan (1901-1981) the idea that schizophrenia is a type of language disorder. We rely on language in order to make sense of the ideas of past, present, and future. When people fail to fully incorporate language into their understanding of the world, they become “schizophrenic,” no longer inhabiting a world in which past, present, and future are distinct. Rather, as “Postmodern” people, we live within a world in which such distinctions in time are impossible. As “schizophrenic” we are isolated from one another and cut off from the future and the past; there is only and on-going present. Without a constructed sense of time, people have a diminished personal identity because a large part of that sense-of- self is the “project” in which a human life is engaged. Lacking a sense of the future one is unable to motivate oneself into a higher level of accomplishment. The anecdote of the 32-year-old man, having taken some college classes but never completing a degree, working a low-paid part-time job, and living in his parent’s basement is a sign that this Postmodern “schizophrenia” may be more than a humorous joke; it may be more real than we want it to be.

The film, Memento (2000), has two timelines, one in color and one in black & white. The film alternates the two. Although the black and white time line is historically first and the color timeline of events occurred later, the color events are ordered in reverse. This shatters the notion of a realistic chronology. Most film critics agree that the viewer of the film is supposed to be confused. This temporal confusion is another marker of a “schizophrenic” postmodern world.

Postmodernism in the world—The Novel

The American novelist William S. Burroughs (1914-1997) is usually classified as one of the most influential of the postmodern writers. We can see his works as “schizophrenic.” Among the writing techniques he used was the “cut-up” in which previously written texts on paper were cut-up into words and phrases only to be recombined into totally different sentences.

In Burroughs’ later works (1981-87) we see a group of 18th century anarchist pirates who attempt to liberate Panama while a late 20th century detective investigates the disappearance of an adolescent boy. The reader is rip-sawn between the two stories full of homoerotic cowboys, Egyptian gods and putrid giant insects. At times characters’ gender shifts. Time, space, and identities are fluid; the commonly accepted realities of the past are ignored. The postmodern novel is a sustained criticism of the ideas of realism and objective points of view. The understanding of time itself as a linear progression from past, to present, and then into the future is undermined. In the postmodern novel things do happen and characters do act, but there is no causal connection between the things that happen, and there is no stable or temporal reality to the characters.

In some cases, the author of the postmodern novel comments directly on those events and may parody the actions of his/her character. Within the novel, The French Lieutenant’s Woman, by John Fowles (1969) the author often breaks into his narrative with his own sense of uncertainty. Fowles says, “This story I am telling is all imagination. These characters never existed outside my own mind.” Later the author again breaks into his narrative saying, “perhaps I now live in one of the houses I brought into the fiction; perhaps Charles is myself disguised. Perhaps it is only a game.”

Jacques Derrida and Deconstruction

One of the most important Postmodern thinkers is Jacques Derrida (1930-2004). His analysis of language and power have been labelled as “deconstruction.” His process of analysis consists recognizing that meanings tend to center on a set of symbols.

Western culture tends to see the world as a set of binary opposites with one privileged term in the center and the other term forced into a marginal role. Examples of this kind of thinking can be found in the following sets of terms: male/female, Christian/non- Christian, white/black, reason/emotion. Within “modern” Western culture, the first term in each of these sets is the dominant term and the second term has been forced into a subordinate role. Derrida claims that Western thought at the deepest analysis behaves in exactly this way. The way in which the privileges are set entitle one group of people over the other, and privileged people have historically often worked hard to maintain their privileges: men over women, Christians over non-Christians, white people over non-white people.

Derrida’s process of deconstruction strives to set these binary terms into an unsettled and ongoing interaction. He does not want to reverse the structure of domination; deconstruction is a tactical process of decentering which reminds us of the fact of domination while simultaneously working to subvert the hierarchy of terms. Derrida’s deconstruction is a radical rejection of foundational kinds of thinking. One advantage of foundational kinds of thinking is the fixed structure of thought; “modern” people prefer to work and live within a society in which the rules and norms are fixed. To upset that fixity can be deeply troubling. But if one happens to be a member of the group of people who are fixed into a subordinate position, then there is an advantage in undermining the fixed system that oppresses one. Derrida himself was a member of two such groups; he was a Jew within a Christian culture and a North African within a Euro-dominate culture. Thus, he saw himself as marginalized by the fixed arrangement of power within his own life.

The history of Western thinking tends to be highly foundationalist: certain ideas are placed centrally and further thought relies on these foundations. One central idea within this system is logic itself. Derrida calls this Western obsession with logical kinds of thinking “logo-centrism.” Western philosophy since the time of Plato and Aristotle (4th century BCE) has assumed the existence of essences: a form of deep truth that acts as the foundation for further human beliefs. So, Derrida argues that Western philosophy has been a process of determining and then speaking directly of these deep essences. Words like Idea, Matter, Authority, the World Spirit, and God have functioned (and to an extent still do function) as foundational essences.

Derrida wants to, first of all, demonstrate that none of these terms can exist purely, rather each term only makes sense within a context that includes its opposite. The “ideal” only makes sense in contrast to the “real.” The term “matter” only makes sense as the other side of “mind.” Secondly, Derrida wants to subvert the priority of the dominant term and set those terms into an ongoing interaction that will not settle into a new relation of domination and submission. When Derrida writes on the opposition between the terms “male” and “female” (which in traditional Western philosophy privileges the male over the female), he does not want to simply reverse the privilege. He realizes that Western thought largely functions as set of binary categories that give meaning to each other; isolated terms cannot have meaning. Even if we use only the word “male” in a sentence and do not mention “female”, the term “male” is itself understood as the opposite of “female” just as the term “female” gets its meaning as the opposite of “male.” Derrida does not think that these binary relations can be undone. What can be undone, through Derrida’s process of deconstruction, is the domination of one of the two terms over the other.

Postmodernism and the criticism of power

This attention to power is part of Postmodern philosophy. Part of the Postmodern criticism of the “Modern” is that “Modern” thinking left the world a terrible legacy of power through sexism, racism, and colonial domination. Within the “modern” mind- set, men were superior to women and are naturally better suited to roles of power; the white races were the more rational-scientific and, therefore, appropriately given power over the non-white races; the nations of Europe and the United States as key beneficiaries of the rational-scientific world view were seen as justified in colonizing the rest of the world. John Locke (1633-1704) is one of the most influential philosophers of “modern” Europe. He is best remembered for inspiring the ideas Thomas Jefferson wrote into the American Declaration of Independence: that all men are created equal. Locke says that “To understand political power right, . . . we must consider, what state all men are naturally in, and is, a state of perfect freedom to order their actions, and dispose of their possessions and persons, as they think fit . . . without asking leave, or depending upon the will of any other man” (Second Treatise, Chap. II, section 4).

However, Locke also wrote the constitution for the American colony of Carolina (1669), which ensures that “Every freeman of Carolina shall have absolute power and authority over his negro slaves …” (article 110). In addition, Locke owned stock in and thus profited directly from the Royal African Company which ran the slave trade for England. Locke saw no conflict between his insistence on the liberty of white Europeans and the enslavement of Black Africans. Since white Europeans (like himself) were by the terms of his own world view a highly rational and scientific society and the people of Africa were not, Locke saw that the Europeans had the right to enslave and dominate people who lacked the rational and scientific tools that were central to European superiority.

Also, when Locke says “men” he means white, European, property owning males, not the whole of the human race, and certainly not women.

In fact, most European men found it “natural” that they would have power over women and Africans. Locke is not a postmodernist; he is a “modern” thinker helping Europeans move away from older models of power. He is arguing against the aristocratic power of kings, dukes, and barons. Locke’s political arguments did help to liberate a class of land-owning European males from the arbitrary power of aristocrats. But it also legitimated the power of white European males in general. No matter how pleasing the words “all men are created equal” may sound to people of the 21st century, Locke (in the 17th century) certainly did not mean to include women or Africans in his conception of freedom. His words marginalized women and non-Europeans.

Postmodern thinkers do NOT want to denigrate the work of Locke or that of Thomas Jefferson; these two men actually worked to enlarge the number of people worthy of being taken seriously as free and able to hold political and economic power. His words helped liberate middle-class, white, European men from aristocratic domination. But neither Locke nor Jefferson worked for the full emancipation of ALL peoples. Rather, by insisting on the legitimacy of middle class, male, white, European, political power, Locke and Jefferson excluded women and non-Europeans from that same kind of power. From a Postmodern perspective, the liberating vision of Locke and Jefferson was not so much “wrong” as it was radically incomplete.

Feminism and the Postmodern

Since Feminism is one of those critiques of power moving in our contemporary world, it seems natural to see the Feminist movement as part of the larger shift in world view that is Postmodernism. One of the Grand Narratives being undermined by Feminism is the seemingly universal distinction between the male and the female and the traditional gender roles that rely on that distinction.

Judith Butler (b. 1956) argues that we should not radically distinguish between “sex” and “gender.” The first is often seen as an irreducible biological category and the second is widely recognized to be socially constructed. But material things (like a human body) are understood through the use of language and thus are (at least to some degree) subject to social construction. Even though Butler considers the word “Postmodern” to be too vague to be useful, she argues that the subordination of women has no single cause or solution; there is no master narrative of “woman” that needs to be overcome.

As we’ve seen, the term “Postmodern” is not easy to define. Nonetheless, there are certain themes or orientations that are commonly considered to be included within that term. Feminism and Postmodernism have in common the criticism of traditional sources of power, especially the power that subordinates one sex to another.

Masculinity and Femininity have no universal qualities; they are concepts that only take on a reality as they are taught to young people who then take up and begin to live those roles. These roles are enforced in society; people are punished or rewarded in various ways for either failing or succeeding in properly living the role given them by their biological sex. Judith Butler calls these lived gender roles “performative.” We are like actors assigned either masculine or feminine roles on the basis of biological sex and expected to perform those roles in our public and private lives. But as “performances” there is no deep reality to these roles we play.

Assigning Blame and the Post-Truth World

There have been numerous articles published in the 21st century claiming that Postmodernism is to blame for all our problems: economic stagnation, cultural relativism, the decline of democracy, social fragmentation, weakening of the family, decline in morality, the existence of alternative facts, and the election of Donald Trump. Postmodernism developed as a criticism of power rather than a tool to further empower the already powerful. When a person holding political power claims that his own views of the world are an “alternative fact,” and thus just as legitimate as any other fact, he is using a very old tool in order to hold on to power; he is using skepticism not Postmodern deconstruction. Powerful people have always been able to wield skeptical tools against the claims of others. In the early 1600s the Church (both Catholic and Protestant) was skeptical of the claims of Galileo that the Earth was a planet that orbited the Sun. In the late 1900s most scientists were skeptical of Darwin’s evolutionary model. The fact that Quantum physics sees the ultimate foundations of the material world as in some part unknowable, does not undermine the science of chemistry’s Periodic Table or the fundamentals of mathematics. Postmodern is not post-truth. What sets the Postmodern world view apart from older forms of skepticism is the radical attempt to open the dialogue to include those who have been systematically excluded: women, people of color, the poor, people who refuse standard gender identities. However, by opening this discussion, room is made for the already powerful to force their own agendas. When powerful people use skeptical tools to downplay the postmodern forces that question their legitimacy, they are NOT being postmodern. They are working within traditional (modern skeptical) frameworks of power. By trying to blame the postmodernists who work to undermine the traditional power-holders (i.e., male, white, Euro-American, gender normative) our modern power- holders work to maintain their own power and blame the problems they themselves have created on those who lack power; this is well-known in political circles as “blaming the victim.”

Why many people resist postmodernism

Let us understand Postmodernism as our current moment in which there is great skepticism of grand narratives (like progress, Christianity and capitalism), a pastiche of styles in the arts, one in which our simulations are so real that they are often accepted as reality, an on-going attempt to “deconstruct” power, and the of diminishing power for white males. Let us further understand that many people (especially, but not exclusively, privileged, older, white, males) are uncomfortable in this environment and miss the “good-old-days” in which their power was unchallenged and the world in which they lived made sense. We should not be surprised that many of these people actively resist the Postmodern age in which they live. People who, during the modern period would have identified as “normal” and “rightfully powerful,” are forced into spaces with people who are NOT just like them. When traditional privilege is questioned and the boundaries between us collapse, the “other” forces its presence on us. Men have to deal with women in power; white people have to adapt to having Black people in power; heterosexuals have to cope with homosexuals in their neighborhoods and families. We should not be surprised that many people have problems in coping with this changing reality.