Chapter 2: The problem of other minds

The problem of other minds

Matthew Van Cleave

Have you ever wondered whether another person might see colors in a radically different way from you—or perhaps that you see colors in a radically different way from everyone else in the world? You might think that we could easily clear up any difference in perception by asking each other questions such as, “Is this green?” But this isn’t what the original question is getting at. Rather, the original question is envisioning the possibility that your red is my green and vice versa. So we all call things by the same color—for example, we all refer to stop signs as “red” and grass as “green”—but what you in your head experience as red, I experience as green. It’s just that I’ve learned to call things I experience as green “red” and things I experience as red, “green.” Notice that if this were the case, it doesn’t seem like there’s any way that we could ever know that our subjective experiences are not the same. Philosophers refer to this possibility as the inverted spectrum. The inverted spectrum envisions a situation where our minds seem to differ radically without us being able to know that they do because we all describe objects in the world the same way but experience them differently. The inverted spectrum draws on a fundamental asymmetry about our own minds versus other minds: we seem to experience our conscious experience in a direct and unmediated way, whereas we experience the conscious experience of others only as mediated through their behaviors, including, importantly, what they say. The inverted spectrum further recognizes the possibility that there could be multiple different kinds of conscious experience that correspond to the same, exact behaviors. One way of putting this is that there is a many-to-one relationship between qualities of one’s conscious experience—green, red, blue, yellow—and the behaviors that those experiences cause, such as saying “green.”

Like the inverted spectrum, the problem of other minds draws on these same two fundamental claims about minds: 1) that we can only have direct, unmediated access to our own minds and 2) that there can be radically different causes of the very same intelligent behaviors. Developing this second claim will lead us to the problem of other minds. In order to do this we will take a little excursion into artificial intelligence and science fiction. Would it be possible for a machine to pass for a person? Could a machine behave in such a human-like way, that we mistake it as a human? The field of artificial intelligence has for many years now taken this question seriously and most within that field take the answer to be “yes.” The idea is that we can engineer intelligence, from the ground up. If you think about it, human intelligence is manifest in certain kinds of behaviors. For example, being able to follow the instructions in setting up a camping tent or in putting together a piece of IKEA furniture. But perhaps the most prototypical intelligent behavior is the use of language. Could we teach a machine to respond intelligently with language—for example, to have a conversation? In 1950, the famous mathematician Alan Turing put forward a way of answering this question—the Turing Test. Turing proposed to reduce the question, “Can a machine think?” to the question of whether a machine could trick a human being into thinking that it (the machine) was another human being, rather than a machine. Turing imagined a human participant communicating with either a computer or a human being via a keyboard; the participant’s task was to determine whether or not she was communicating with a machine or a human. In order to do so, the participant could ask any question they liked, including questions like the following: “Imagine a capital letter “D” and rotate it 90 degrees to the left. Now place the “D” atop a capital letter “J.” What object does this remind you of?”[1] If the machine were able to make the human think that it was actually a human (and not a machine), then, Turing claims, we should consider that machine to be intelligent. Turing thought that machines would eventually be able to pass this test—they could trick a human into thinking it was not a machine—and that therefore machines could think.

But there another interpretation of what’s going on here, which is that such a machine would only give the illusion that it was thinking. That is, such a machine would behave as if it were thinking, but it wouldn’t really be thinking because it was really nothing other than an ingenuously designed mechanism that behaved in a way that was indistinguishable from things (like humans) that can truly think. The idea is that humans have minds (and thus thoughts) but that machines don’t have minds (and thus don’t really think). Rather, machines only behave as if they are thinking; they appear intelligent, but really aren’t.

But now notice where this response puts us. We have admitted that there could be things that behave indistinguishably from intelligent beings but that lack minds. If this is so, then it raises the question: how do we know that human beings other than ourselves have minds? For all we know, other human beings could be nothing other than being who behave intelligent (they act—speak and behave—as we would expect intelligent beings to act) but they don’t really have minds. Rather, what drives their intelligent behavior is nothing other than an ingenuous mechanism. Of course, in one’s own case, one knows that one has thought because one can observes one’s own thoughts directly, it seems. But in the case of others, we can only infer the existence of their minds/thoughts through their behaviors. And since we have noted that sometimes the very same intelligent behaviors could be caused by things without minds (for example, computer programs), we cannot rule out that in the case of other people the same sort of thing is occurring—their speech and behavior is caused by ingenuously designed, but ultimately mindless, mechanisms. Perhaps you are unique in the universe in that only you have thoughts; everyone else is just a mindless machine, like Turing’s computer program that passes the Turing Test. This skeptical scenario—that you are the only thing in the universe that thinks and has a mind—is what philosophers call solipsism. Solipsism is the skeptical scenario that defines the problem of other minds. The problem of other minds is simply that you cannot rule out solipsism; all of your experience is consistent with the possibility that you are the only thing in the universe with a mind. Of course, no one actually believes this but the skeptic’s point is that you cannot rule out this seemingly absurd possibility. Here is the skeptic’s reconstructed argument:

- If we cannot rationally rule out that solipsism is true, then we cannot know that other people have minds.

- We cannot rationally rule out that solipsism is true.

- Therefore, we cannot know that other people have minds.

This argument is a valid argument—that is, the conclusion of the argument must be true if the premises are true. Thus, if there’s a flaw in the argument it would have to be that one of the premises is false. As we will see in the following section, philosophers have taken aim at both premises and attacked the argument in very different ways.

There is another way of presenting the problem of other minds that will help us to zero in on an important aspect of what “mind” means in the context of the problem of other minds. This way of presenting the problem relies on the concept of a philosophical zombie. A philosophical zombie is an imaginary creature that behaves indistinguishably from a normal human being but who lacks any conscious experience of the world. A philosophical zombie is, so to speak, dead inside—it doesn’t experience anything. Of course, a philosophical zombie won’t know it is a philosophical zombie. It will answer questions like the above “D”-umbrella question correctly and it will be able to describe the fragrance of a rose and distinguish that smell from the smell of coffee. It will be able to talk about food it likes and the things that turn it on sexually. That is, it will behave and speak in a way that is indistinguishable, from an outside perspective, from a normal human being who does has these different conscious experiences. But its insides will be like the insides of a rock—there’s nothing there. This isn’t to say, of course, that there isn’t a complex mechanism (the brain) that is causing all of these intelligent behaviors. Rather, it is just to say that there is no conscious experience attached to the mechanics of the brain. The neurons do what they do in causing the behaviors; there just isn’t any conscious experience connected with the functioning of those mechanisms.[2] Thus, we can restate the problem of other minds in terms of the skeptical scenario in which everyone in the world except you is a philosophical zombie. How could you know this isn’t the case? Again, it isn’t that the skeptic thinks that this is that case; rather, it’s that the skeptic think you can rule it out and therefore that you can’t know that other people have minds.

This way of setting out the problem makes is clear that the aspect of mind that is operative in the “problem of other minds” is that of conscious experience. If all we meant by “mind” was simply whatever it is that causes a certain class of behaviors (namely, those we deem “intelligent”), then there is no problem of other minds. In that definition of “mind,” the computer that passes the Turing Test has a mind and so does the philosophical zombie, since in both cases there is something that is causing those intelligent behaviors. Defining the mind in this way enables us to verify the existence of minds in a third-person type of way—that is, I can know that you have a mind because I can know that you engage in intelligent behaviors (such as conversing with me). However, if we focus on the conscious experience aspect of minds, then this seems to be something that can be known only in the first-person. That is, I alone have direct access to my own conscious experience; the conscious experiences of others can only be inferred through observations of others’ intelligent behaviors. But since these intelligent behaviors could be caused by things that aren’t conscious, I cannot confidently infer that others have conscious experience. That is the problem of other minds.

Ludwig Wittgenstein had his own way of addressing the problem of other minds. See if you can understand what Wittgenstein is saying in the following passage.

“If I say of myself that it is only from my own case that I know what the word ‘pain’ means—must I not say that of other people too? And how can I generalize the one case so irresponsibly?

Well, everyone tells me that he knows what pain is only from his own case!—Suppose that everyone had a box with something in it which we call a ‘beetle.’ No one can ever look into anyone else’s box, and everyone says he knows what a beetle is only by looking at his beetle.

Here it would be quite possible for everyone to have something different in his box. One might even imagine such a thing constantly changing.— But what if these people’s word ‘beetle’ had a use nonetheless?—If so, it would not be as the name of a thing. The thing in the box doesn’t belong to the language-game at all; not even as a Something: for the box might even be empty” (Philosophical Investigations, §293).

Wittgenstein uses a metaphor of a “beetle in a box.” What are the beetle and the box metaphors for? (If you don’t know, reread it and think about it before proceeding.) The box is a metaphor for the mind—this is why we cannot see into others’ boxes; other people’s minds are “black boxes.” This is Wittgenstein’s colorful way of putting forward the Cartesian[3] view of mind on which the problem of other minds depends. The Cartesian view of mind, as I use that term here, just refers to the idea that I can know my own mind in a direct and unmediated way, whereas I can only know the minds of others indirectly, through their behavior. The beetle is simply a way of referring to an individual’s conscious thoughts and sensations. So I can see my own beetle/thoughts because it exists in my own box/mind, but I cannot see others’ beetles/thoughts because they exist in others’ boxes/minds. Now look at what Wittgenstein says in the last (third) paragraph of the above passage: it is “quite possible for everyone to have something different in his box.” Do you see how that is just a colorful, metaphorical way of raising the inverted spectrum problem? Now look at the very last line: Wittgenstein envisions that the box could be empty and we would be none the wiser. Do you see how this is a metaphorical way of raising the problem of other minds? People might be talking intelligently about their beetles/thoughts even if there really aren’t any beetles/thoughts. Wittgenstein’s point is that we (our language) is not able to penetrate into the minds of others. That we cannot do so is what gives rise to the problem of other minds. We cannot know that the words people speak have any thoughts/sensations tied to them. We can know in our own case but we cannot know in the case of others. Wittgenstein actually has his own kind of solution to the problem of other minds that he hints at here, but we will save a discussion of that until the next section when we consider some of the famous attempts to solve the problem of other minds.

Study questions

- True or false: If someone’s color spectrum were inverted relative to mine (and had always been so since they were an infant), I would be able to discover this by asking them questions such as “is this thing red or green?”

- True or false: The Turing Test enables us to discover whether or not someone has conscious thoughts and sensations.

- True or false: The Turing Test was conceived as a test that would enable us to answer the question: “Can a machine think?”

- True or false: The aspect of “mind” that is operative in the problem of other minds is that of conscious experience.

- True or false: Wittgenstein’s “beetle in the box” can be seen as a metaphorical way of describing both the inverted spectrum and the problem of other minds.

For deeper thought

- If we were to define the mind as “the thing that causes intelligent behaviors” then would there still be a problem of other minds? Why or why not?

- Does the skeptic think that other people don’t have minds? Why or why not?

- What is the “Cartesian view of mind”?

- Even if I can’t know others’ minds directly, can’t I still know them by inferring based on their behaviors? For example, if someone is crying and I ask why and they say that their grandfather just passed away, can’t I rationally conclusion that they are sad? And if it is rational to say that they are sad and if sadness is a thought or sensation that require a mind, then isn’t is rational to say that they have a mind? What might the skeptic say in response to this reasoning?

- Suppose a neuroscientist were to say: “I can solve the problem of other minds, just let me show you inside the brain and you can see all these billions of neurons doing their thing. Since the mind is the same thing as the brain, I have just proved to you the existence of other minds (since this brain is something you can observe in action and it is not your brain).” How might the skeptic respond to the neuroscientist?

Responses to other minds skepticism

We will consider two types of responses to other minds skepticism: the “analogical inference” solution and the behaviorist solution. The analogical inference solution that we will consider comes from the 20th century philosopher, Bertrand Russell (1872-1970). Here is Russell’s reconstructed argument:

- I know through introspection that in my own case, conscious mental states (M) regularly precede many of my intelligent behaviors (B).

- I can observe similar kinds of intelligent behaviors (B), in others.

- Therefore, based on the similarity of (B) in me and (B) in others, (B) in others are probably regularly preceded by conscious mental states (M).[4]

Suppose that I am working on a tough math problem, or figuring out how to respond carefully to a sensitive issue in a text message, or figuring out what my next move should be in a game of chess, or saying “that smells wonderful” after smelling a lilac bush. In all of these cases I am often aware of the conscious thoughts I am having and I recognize that my intelligent behavioral responses are regularly preceded by those conscious thoughts. Notice that whereas my conscious thoughts are something that only I have access to, the behaviors are something that I can equally well observe in both myself and others.[5] Since in my own case I can observe both my conscious thoughts, on the one hand, and the intelligent behaviors, on the other, I am able to establish a correlation between them: M → B (read this as “M reliably precedes B”). So, for many of the intelligent behaviors I observe (namely, my own), I can observe that they are preceded by conscious mental states. But I can also observe many intelligent behaviors of others. For example, if my friend Grace says, “that lilac bush smells wonderful” after smelling a lilac bush, then this is one of her intelligent behaviors that I can observe. Although I cannot observe her mental states (such as the smells that she smells), I know that when I make similar statements in similar situations, my behaviors correlate with mental states (for example, the delightful fragrance of a lilac bush) which I do have access to. Or, when Grace puts my king in check with her queen and then says “check,” I cannot observe the conscious thoughts that she has when she does this, but I do know that when I do similar things (that is, when I put others into “check” in a game of chess), those behaviors are correlated with a series of conscious thoughts.

Russell thinks it is perfectly rational to assume, based on the correlation, M → B in my own case, that the same thing holds for others, based on the strength of analogy between our intelligent behaviors, which are very similar.

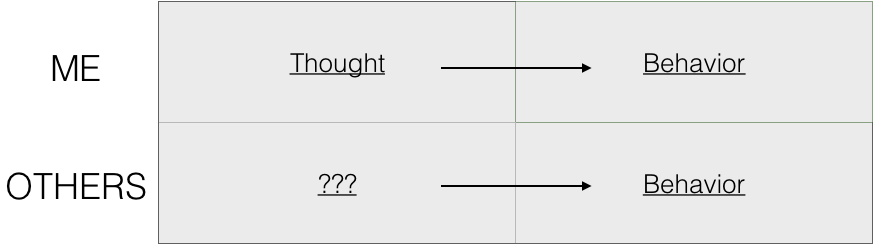

This figure depicts the analogy in Russell’s analogical argument. The strength of the argument rests on the strength of analogy between my behaviors and the behaviors of others. Are they really very similar or are they quite different?

Russell’s claim is that they are very similar and so we should think that they are similar in other respects, too. The problem of other minds says that we do not know whether others have conscious thoughts; Russell thinks we do know this because 1) our own intelligent behaviors are similar to the intelligent behaviors of others and that therefore, 2) we can generalize from our own case to the case of others.

However, a problem immediately arises for Russell’s solution: if I have observed many more intelligent behaviors in others than in myself, isn’t my generalization from my own experience a hasty generalization? A hasty generalization is an informal logical fallacy according to which one makes a generalization to a whole population based on too few examples. For example, if the first Michigander I met owned a canoe and based on that one Michigander I asserted, “All Michiganders own canoes,” then that would be a hasty generalization. I am generalizing to all Michiganders from my experience with only one Michigander. That does not seem like a very strong logical inference. Perhaps the Michigander I met was idiosyncratic and not representative of all Michiganders. The problem is that Russell seems to be committing exactly this fallacy in his solution to the problem of other minds. Suppose I have 100 friends, all of whom I believe have minds like mine and all of whose intelligent behaviors I have observed. I also have observed, in my one instance, the correlation, M →B. But how can I legitimately infer based on this one case that this correlation holds in all of the other cases (for example, that it holds in the case of all of my 100 friends)? That is a hasty generalization, par excellence. It is making the same mistake as inferring that all Michiganders own canoes from my experience with one Michigander who owned a canoe.

Here is the relevant passage in Russell where I think he makes the fatal error:

“If, whenever we can observe whether A and B are present or absent, we find that every case of B has an A as a causal antecedent [in our own case], then it is probable that most Bs have As as causal antecedents [in the case of others], even in cases where observation does not enable us to know whether A is present or not.”

I have added in bold text and square brackets the explicit assumption that Russell needs in order for his analogical argument to work. But when that assumption is made explicit, it is clear what the problem is: what entitles Russell to assume that my own case is the same as the case of others? To assume that they are would seem to commit the fallacy of begging the question against the other minds skeptic. And if we actually think of how the generalization works, it is a bad generalization—it is a hasty generalization. This is what Wittgenstein is getting at in the above passage when he says that in assuming that the meaning of “pain” is given by my subjective conscious experience, I “generalize the one case so irresponsibly.” Wittgenstein is making the same point that I have been making (in addition to others): that generalizing from my own conscious experiences to the conscious experiences of others is a hasty generalization.

After all, for all I know everyone else is a philosophical zombie and I alone am unique in having conscious experiences. Without having further knowledge of other Michiganders, it would be totally irrational for me to infer that all Michiganders own canoes based on only the one case; without having further knowledge of others’ minds, it would be totally irrational for me to infer that others have conscious mental states, based only on my own case. The problem is that whereas I can go and observe other Michiganders and their canoe- owning propensities, I cannot observe others’ minds to determine whether they have conscious experience. Therein lies the problem of other minds.

I do not see how Russell can answer the above objection. It seems that either he committing a hasty generalization (if he is generalizing from one’s own intelligent behaviors to the intelligent behaviors of everyone else) or he is begging the question (if he is assuming that all intelligent behaviors—my own and others—are similar in all respects). It is important to see that Russell accepts, and does not question, the Cartesian view of mind that gives rise to other minds skepticism. One might think that that is the problem: once one accepts the Cartesian view of mind, the problem of other minds is unavoidable. This is what the behaviorist solution attempts to challenge. However, in an important sense, the behaviorist solution to the problem, isn’t really a solution at all, but rather a rejection of the problem in the first place. The behaviorist thinks that the problem of other minds is only a problem because it assumes a mistaken view of the nature of the mind. Thus, I prefer to refer to the behaviorist solution as a dissolution of the problem, since it rejects the terms in which the problem is presented. Dissolutions of philosophical problems reject that the problem really is a problem. Thus, they attempt to show what the mistaken assumptions are that give rise to the problem. The behaviorist dissolution to other minds skepticism does this by rejecting the Cartesian view of mind on which other minds skepticism depends. In contrast, Russell’s attempted analogical inference solution to other minds skepticism accepts the Cartesian view of mind on which other minds skepticism depends.

The behaviorist dissolution of other minds skepticism

According to the behaviorist tradition[6], the mind is as the mind does. The mind is not best conceived as a private domain that only the subject has access to, as the Cartesian view of mind holds. Rather, “mind” is just a fancy way of referring to a certain class of intelligent behaviors or to the input/output functions of the brain. The 20th century Oxford philosopher, Gilbert Ryle famously referred to the Cartesian view of mind as “the dogma of the Ghost in the Machine.” This phrase captures the Cartesian idea that there was some private domain inaccessible to anyone except the subject herself (“ghosts”) and that doesn’t function according to the normal physical laws that govern physical things (“machines”). Minds, according to the Cartesian view, are mysterious, ghostly things that cannot be explained in terms of scientific principles. The behaviorist tradition seeks to overturn this view of the mind as something ultimately mysterious and seek to replace it with a view according to which the mind can be studied scientifically like any other object in the universe. If Cartesians are ghost hunters, behaviorists are Penn and Teller calling “bullshit.”

As Ryle notes, the problem of other minds is a direct consequence of the Cartesian view of mind:

“Not unnaturally, therefore, an adherent of the official theory finds it difficult to resist this consequence of his premises, that he has no good reason to believe that there do exist other minds than his own” (Concept of Mind, p. 3).

But there’s really no problem if the mind isn’t some private domain but, rather, something publicly accessible. The typical behaviorist way to try to convince people of this is to focus on language—to think about the language we use to describe minds rather than to think about minds themselves. Behaviorists like Ryle and Wittgenstein were keen to analyze our language and to understand how language works because they believed that language was often something that misled us regarding the nature of things. Once we understand how language is meaningful, including what our words refer to, many traditional philosophical problems will be revealed as pseudo-problems—problems based on a misunderstanding rather than actual, deep problems. For behaviorists, the mind is nothing other than the way we refer to the mind using certain kinds of mental terms, such as pain, hope, fear, intelligence, and so on. The key to understanding the nature of the mind is to understand how these terms become meaningful to us—what they must refer to if we are to learn their meaning.

A good example of a behaviorist doing this is Wittgenstein in the “beetle in the box” passage cited earlier. It is clear in that passage that what Wittgenstein is attempting to understand is how we learn the meaning of a mental term like “pain.” The traditional idea is that we learn the meanings of terms like “pain” by singling out a kind of experience in our mind’s eye and then having that experience be the thing that our term “pain” refers to. Wittgenstein’s point in that passage is that this can’t be right because in that case it is possible that our words could refer to radically different things and yet we would never know it. It might even be the case that a person had no experience at all—no beetle in their box. Wittgenstein’s point is that our terms don’t get their meaning by referring to some inner, private domain of our conscious experiences. Rather, our mental terms get their meaning by how we use them and they always, in the end, refer to publicly observable phenomena.

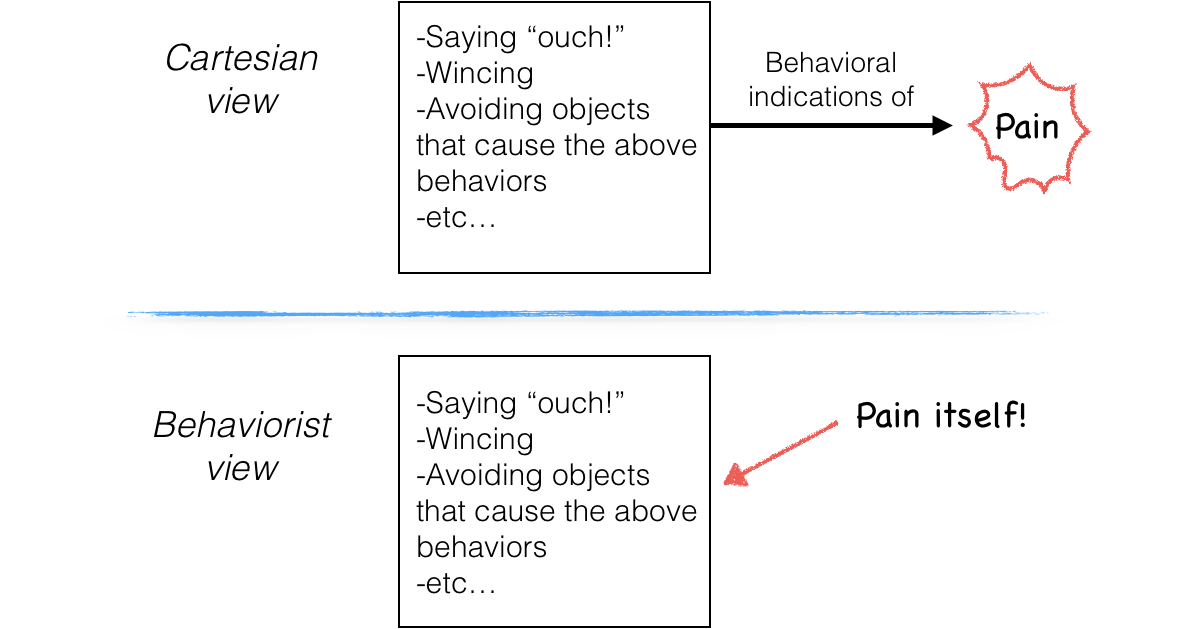

Gilbert Ryle followed Wittgenstein’s lead in this and put forward his own behaviorist conception of how our mental terms get their meaning. The figure below gives a nice comparison of the Cartesian and behaviorist accounts of the meaning of our mental terms—terms like “pain.”

As you can see, for Ryle pain isn’t some inner, hidden phenomena; rather, “pain” refers to certain kinds of observable behaviors—saying “ouch,” wincing in pain, having the tendency to avoid objects that have caused pain in the past, and so on. These behavioral manifestations of pain just are what pain is for Ryle, whereas for the Cartesian they are merely behavioral indications of a private conscious experience. For the behaviorist, however, there’s nothing further that the term “pain” could refer to—certainly not to any internal conscious experiences. After all, how could we ever learn the meanings of mental terms if they referred to things that our mothers couldn’t show us? Wittgenstein’s point was that there can’t be because anything that is essentially private is not something that could figure into the meaning of a publicly shared language.

Ryle has a nice analogy that he used to illustrate the kind of thing that a mind is. Imagine a person who doesn’t yet understand what the term “average taxpayer” means. This person is puzzled by the fact that they have never encountered this “average taxpayer” in real life. How mysterious a person this “average taxpayer” must be! They appear in all kinds of official documents talking about facts about the country, but they have never been encountered in real life! The mistake this person is making, of course, is that they are thinking that “average taxpayer” refers to some concrete particular object when in fact it refers to a more abstract object—to the economic average of a whole country. Particular taxpayers are things that we encounter in time and space (Bob, Sue, Sally) but “average taxpayer” is not that kind of thing. Ryle thinks that the Cartesian view of mind makes a similar mistake—what he calls a “category mistake”—in trying to locate the mind in the realm of concrete particular objects. The mind is not a concrete particular object, Ryle thinks, but a kind of abstract object, like “average taxpayer.” “Mind” is simply a shorthand way of referring to a range of different mental terms that themselves designate various types of intelligent behaviors.

That doesn’t mean that minds aren’t real; it just means that we go awry, and thus lead ourselves into confusions, when we go looking for minds in the world of concrete particular objects.

How does the behaviorist conception of mind solve the problem of other minds? Fairly straightforwardly. Other minds skepticism gets its teeth from the idea that minds seem to be something that we have only first-person access to. This means that we can only know our own minds directly and can only know others’ minds indirectly, based on their behaviors. Since those behaviors could be associated with very different inner experiences—including, crucially, no experiences at all—and we cannot rule out that this isn’t the case, it follow that we cannot know others have minds. The behaviorist conception of mind rejects that minds are something that can only be known in the first-person. Rather, “minds” are a kind of abstract object that consists of an assemblage of all the different mental terms that we use. And since these mental terms refer to publicly observable phenomena, it turns out that we can know other minds just as directly as we can know our own minds!

What should we say about the behaviorist dissolution of the problem of other minds? Is it successful? It does seem that there’s something that the behaviorist conception of mind neglects—the fact that we do, in our own case, have conscious experiences and that these conscious experiences seem to be an important part of what minds are. A philosophical zombie seems to be a radically different being than we are—even if we have no way of knowing whether someone is a philosophical zombie or not. One way of revealing what seems to be wrong with the behaviorist conception of mind is by way of a famous intellectual joke:

Behaviorist #1 to Behaviorist #2: (after a romantic romp in bed): That was good for you, how was it for me?

The joke, of course, is that it seems absurd to not know how an experience like sex was for oneself. You don’t need to observe one’s own behaviors to answer this question. But it seems that this is exactly what the behaviorist is saying. We can make the same point about pain: if you hit your thumb with a hammer you don’t have to observe yourself saying “ouch” and wincing in pain in order to know that you are in pain! Thus, the problem for the behaviorist view of mind is that it seems to neglect the reality of conscious experience. Even if people like Wittgenstein and Ryle are correct about the meaning of mental terms, it seems that we can nevertheless meaningfully ask the question about whether other people have conscious experiences like my own—or even have them at all! That this seems like a perfectly meaningful question one can ask about the world mitigates against the behaviorist’s attempted dissolution of the problem of other minds.

Thus, if Russell’s attempt to solve the problem of other minds skepticism fails (as I have argued) and if the behaviorist’s attempted dissolution of other minds skepticism is also unsuccessful, then we are still without a solution to the problem of other minds. This doesn’t mean that we haven’t made progress, however, since sometimes knowing what doesn’t work is part of how you get to a solution that does work. Whether or not there is a solution to the problem of other minds continues to be something that philosophers debate. And the one of the most fundamental divides within this debate turns on the two views of mind that I have introduced above: the Cartesian and behaviorist views of mind. These two camps mark radically different ways of approaching a range of different philosophical questions the concern the mind.

Study questions

- True or false: Russell’s analogical inference solution to other minds skepticism accepts the Cartesian view of mind.

- True or false: Russell thinks that since we can know our own minds directly and can correlate our conscious experiences with our intelligent behaviors, we can rationally infer that others also have conscious experiences attached to their intelligent behaviors (even though we can’t observe those conscious experiences).

- True or false: The Cartesian view of mind and the behaviorist view of mind agree that we mental terms like “pain” refer to the publicly observable behaviors, such as someone yelling “ouch!”

- True or false: Behaviorists attempt to reorient philosophical questions about the mind (such as the problem of other minds) from the mind itself to how we talk about the mind.

- True or false: According to Ryle, minds are kind of concrete particular object, albeit one that isn’t physical—like a ghost.

For deeper thought

- What is the difference between concrete particular objects and abstract objects? Give an example of each type of object.

- What is the difference between a solution to a philosophical problem and a dissolution of a philosophical problem?

- Can you think of a better solution to the problem of other minds—one that doesn’t encounter any of the problems of the above solutions? That is, is there a way of acknowledging the reality of conscious experience but that doesn’t lead to other minds skepticism?

- Why does Wittgenstein think that inner conscious experiences are irrelevant to the meaning of mental terms like pain? Do you think he is correct about this? Why or why not?

- According to Ryle, how is the term “average taxpayer” similar to the term “mind”?

- The correct answer is: an umbrella. This example comes from Daniel Dennett. ↵

- Are philosophical zombies logically possible? One way of seeing that they are is by considering blindsight patients. Blindsight is a neurological disorder in which patients can correctly respond to questions about something in their visual field although they have no conscious experience of that field of vision. The reality (made clear in blindsight patients) that information can be conveyed from the visual system to the executing processes that govern behavior and speech without there being any conscious awareness of the properties conveyed through vision is an existence proof of the possibility that a philosophical zombie represents in the extreme. ↵

- The term “Cartesian” is just a way of referring to the ideas of Rene Descartes, the 17th century philosopher who was introduced in the chapter on external world skepticism. So the “Cartesian view of mind” is a just a way of referring to the concept of the mind that Descartes held. ↵

- I should note that Russell himself argues something stronger than what I’ve presented here. Russell thinks that we can discover in our own case that M causes B. But I have presented the weaker claim that M and B are correlated since the weaker claim is all that is needed to support the inference to other minds. Russell’s claim that M causes B (and that this is something he can know via introspection) is problematic. Philosophers will recognize that my reconstruction raises the problem of epiphenomenalism which Russell’s formulation doesn’t. ↵

- One way of putting this is that conscious experience is first-person accessible, whereas behaviors are third-person accessible. The astute reader should recognize that this is the Cartesian view of mind. ↵

- Here I include within the behaviorist tradition the heir of behaviorism, functionalism. Although there are important differences, both behaviorists and functionalists see the mind as essentially tied to actions. Whereas traditional behaviorists treat the brain as a kind of black box, functionalists, influenced by modern-day cognitive science, try to understand the input-output functions that the brain instantiates. ↵